Home >

Matabeleland South >

Travel by Ox-wagon in the 1890’s – Lt-Col H. Vaughn-Williams recollections after 57 years

Travel by Ox-wagon in the 1890’s – Lt-Col H. Vaughn-Williams recollections after 57 years

Background

Lieutenant-Colonel H. Vaughn-Williams (the author, who I shall call ‘H’ because he never reveals his first name) was a nineteen year old beginning medical studies at Edinburgh in 1889 when his brother Arthur persuaded him to interrupt his studying for a year and accompany him to Matabeleland. Arthur, twelve years his senior, was a keen sportsman and when hunting in Northern Zululand had become good friends with Johann Colenbrander.

On Arthur’s return from Africa in 1887 he had joined a firm of London stockbrokers with his hands-on knowledge of the new South African goldmines on the Witwatersrand. About March 1889 in London, Arthur bumped into Johan Colenbrander, who was now working with Renny Tailyour for a concession from Lobengula on behalf of a rich German industrialist, Eduard Lippert, who had been granted a dynamite monopoly by Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic (See the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) Colenbrander had suggested to Arthur that he raise a few thousand pounds, form a syndicate and he, Colenbrander, would assist him in every way to get a mineral concession from Lobengula with whom he was on good terms.

Arthur asked his younger brother H if he would accompany him and he jumped at the chance. The book that he subsequently wrote of his time at Gubulawayo over 57 years later is called A Visit to Lobengula in 1889. His visit was at a critical time, the Rudd Concession had been signed in October 1888, rumours of Rhodes’ impi, the Pioneer Column, were rife in Matabeleland and the Matabele people believed there was a very real threat to their Matabele nation. See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession? under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Feelings against the white people in Gubulawayo, the traders, hunters and concession seekers, ran very high and if not for Lobengula’s protection, they would surely have been massacred. The article A Visit to Lobengula at the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha in 1889 – Lieut-Col. H. Vaughn-Williams recalls his stay after 57 years under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com records this period. This article describes the method of travel to Gubulawayo in those days.

Colenbrander and E.A. Maund had escorted Lobengula’s indunas to see Queen Victoria

Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele, had sent Mshete (Umshete) and Babayane as personal envoys to meet Queen Victoria as head of the British Empire. Maund had been a sergeant-major in the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) and Mathers in Zambesia; England’s Eldorado in Africa quotes Maund, who was the local representative of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and also the correspondent for The Times, as saying he asked for a gold mining concession in Mashonaland from Lobengula who was receptive to the idea of the English keeping the Portuguese at bay and replied: “But Maundy, I want you to do something for me first. They tell me that the white queen no longer exists and that is why the white men come up here and bother me. I want you to take two of my men home to see whether the white queen is living.” Maund said he agreed to the King’s request as there was no imperial government representative in the country, John Moffat being elsewhere, but it is likely he really hoped to upstage Rhodes.

Lobengula dictated a letter that the Rev Charles Helm checked that said: “Lobengula desires to know that there is a queen. Some of the people who come into this land and tell him that there is a queen, some of them tell him there is not. Lobengula can only find out the truth by sending eyes to see whether there is a queen. The Indunas are his eyes. Lobengula desires, if there is a queen, to ask her to advise and help him, as he is much troubled by white men who come into his country and ask to dig gold. There is no one with him whom he can trust and he asks that the queen send someone from herself.”

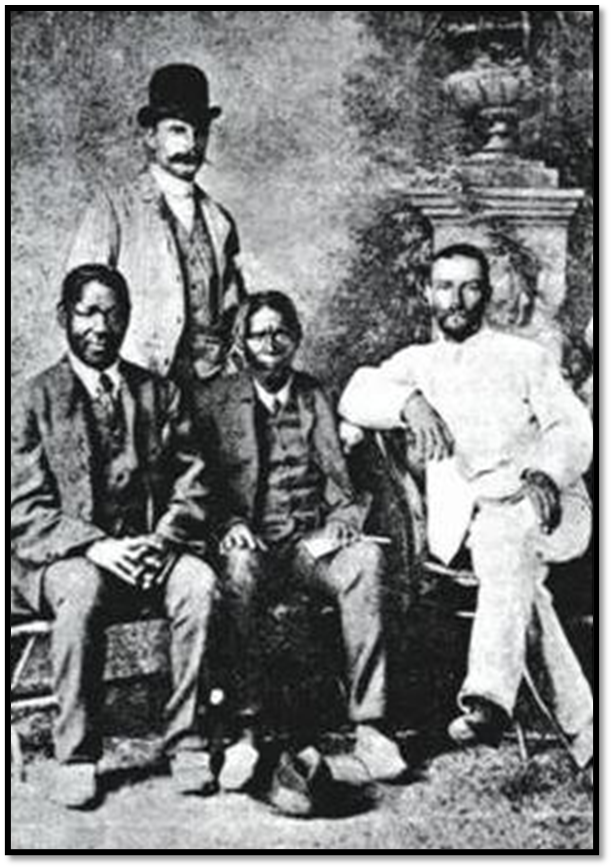

Babayane, Edward Maund, Mshete and Johan Colenbrander (translator) in London

In reply to Lobengula’s clear concerns concerning the sovereignty of the Matabele nation, the Queen’s reply was somewhat ambiguous and did not offer any real solutions: “In the first place the Queen wishes Lobengula to understand distinctly that Englishman who have gone out to Matabeleland to ask leave to dig for stones have not gone with the Queen's authority and he should not believe any statements made by them or any of them to that effect. The Queen advises Lobengula not to grant hastily concessions of land, or leave to dig, but to consider all applications very carefully. It is not wise to put too much power into the hands of the men who come first and to exclude other deserving men. A King gives a stranger an ox, not his whole herd of cattle, otherwise what would other strangers arriving have to eat?” (See the article Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

They leave for South Africa

On the 30 March 1889 the Vaughn-Williams brothers, Arthur and H, sailed from Plymouth on the Grantully Castle, the same ship as Maund’s party that included Colenbrander, Condon, Beaumont and the two indunas Mshete and Babayane – Maund himself left a week later. First stop was Lisbon, then Madeira where divers in small boats would dive underwater to fetch sixpences and shillings but refused pennies! Tenerife was passed before a stop at Ascension Island and then St Helena where some army officers disembarked and after twenty-two days at sea they arrived at Cape Town. The usual advice they had on saying they were going to Matabeleland was they were mad: “A most dangerous place and the natives all looking for trouble. Don’t you go.” Young Vaughn-Williams was puzzled by the old-timers’ toast: “Here’s the skin off your nose” but soon learned on trek that his nose peeled its skin every ten days from the sunburn and wind!

Journey to Kimberley and equipping the expedition

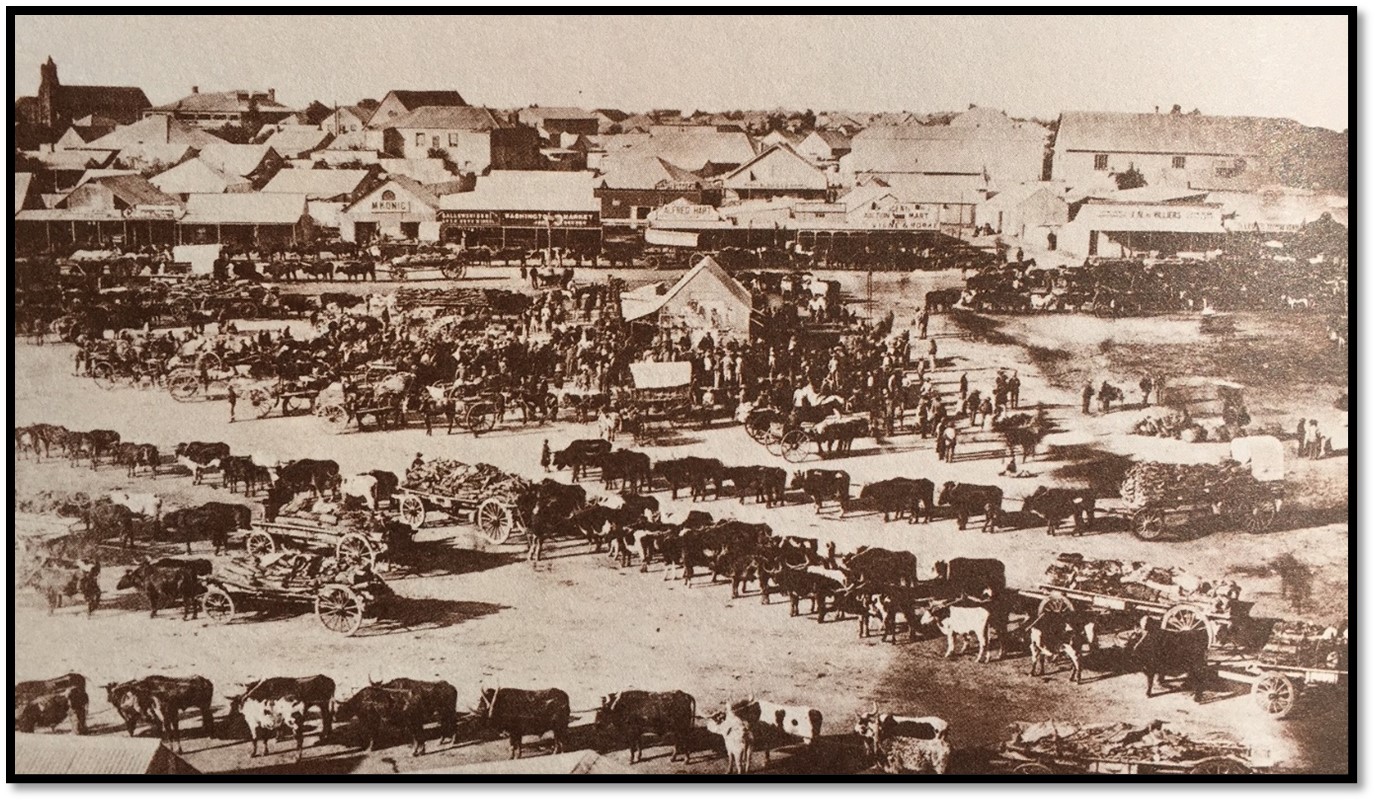

The train journey to Kimberley is described as long and dreary and only reached after two nights. The brothers stayed in a wood and corrugated iron hotel on the market square, the Kimberley Club was the only brick building in town.

Photo from the Heritage Portal: Market Square, Kimberley circa 1888

A large amount of supplies were needed, including two half-tented ox-wagons for sleeping in, each capable of carrying about 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) Boer meal at £5 a 200 lb bag, bags of mealie meal, sugar, salt, tea and coffee beans, cases of bully beef, tinned milk, jam and pickles, curry powder, bags of onions and potatoes, two small barrels of Cape brandy, whisky and a case of champagne. Most of the goods were bought from Hill and Paddon, the leading store on Market Square.

Tools included axes and hammers. Beads for bartering were chosen carefully as fashions changed in Matabeleland and much advice had to be sought. Eventually large quantities of small black beads, blues of different shades and white were bought. Bales of blankets and blue cloth (eelambo) for trading, two yards would buy most things. Also bars of lead, percussion caps and gunpowder.

The ox-wagons had kartels, a wooden hammock for sleeping on with interlaced raw hide reimpjies to take a mattress. A full-sized ox-wagon is 18 ft long (5.5 m) with the hooded tent at the rear about 8 ft long (2.4 m) with plenty of space under the kartel for storing personal clothes and possessions. The oxen were carefully chosen from neighbouring farmers. Two spans of sixteen and eight spare oxen were bought, a total of forty, all supposedly salted[i] from lung sickness, one of the curses of the veld in those days.

Trek gear included chains, yokes, yoke skeys, dozens of reims, neck strops as well as ox whips were bought. The whips had a thin bamboo stick about 12 feet long (3.7 m) and a lash of about 20 feet (6 m) often made of giraffe hide, with a thin lash, or voorslag at the end, usually of blesbok or kudu hide. Good drivers were said to be able to flick a fly off one of the leading oxen! In addition, they carried an agter or sjambok to drive the after or hind oxen that carried the disselboom of the ox-wagon and these were made of rhino or hippo hide and at least 6 feet long (1.8 m)

Packing was carefully done, with heavy goods below the belly or buik of the ox-wagon. Valuable items, such as champagne and whisky were also packed here, so they were difficult to get at! Two large tarpaulins, or bucksails were added large enough to cover the whole of each wagon and when outspanned could be laced down to the wheels by eyelets to keep off the rain.

There was difficulty getting salted horses, although they managed to buy four to haul another purchase, a Cape cart and a shooting pony.[ii]

Social activities at Kimberley; they meet Rhodes

During their stay H played rugby twice a week for Kimberley Club although the grounds were knobbly, hard-baked earth and he says when you fell or were collared, you were apt to have all the skin taken off your knees and elbows. There were dances, concerts, a circus was in town and an operatic company called the Luscombe Searelle Company. A big prize fight took place between a man called Cooper who Arthur had sparred with and a Jewish prize fighter called Bendorff, who they watched training in Kimberley and had been brought from England by Barney Barnato. The fight took place in Johannesburg and Cooper won easily.

He says although they met Rhodes several times at the Kimberley Club, they were not much impressed by him. He had a high-pitched voice and it always seemed his thoughts were elsewhere even when he talked to them. He was apparently quite unpopular in Kimberley having bought up all the smaller diamond mining operations in the Kimberley area and having in March 1888 launched De Beers Consolidated Mines with funding from N.M. Rothschild and Sons. Many Kimberley residents said they had been squeezed by Rhodes so they had to sell or get out of the diamond business – the general opinion was that he was a ruthless man and would do anything to get his way.[iii]

Maund, also seeking a concession from Lobengula, tries to deter them

They had journeyed with Colenbrander, Condon and Beaumont from England, but Maund was not keen on their friendship, being jealous about obtaining a concession from Lobengula and did all he could to prevent the Vaughn-Williams brothers from going to Matabeleland. There was a great deal of jealousy between the rival concession seekers; even their friend Condon came over, instructed by Maund, to describe all the dreadful killings[iv] that had taken place in Matabeleland and begged the brothers not to go.

The brothers collect an ox-wagon crew together

Finding good drivers and servants was difficult. They managed to find two good drivers, who they describe as Fingoes.[v] The elder was middle-aged, named April and the younger was Paul. Two youngsters of 14-15 years old from the Cape were recruited as leaders or Voorloopers and an amaNdebele named George, who had worked on the mines at Kimberley and now wished to return home to Matabeleland, was hired as cook. Although not much of a cook, he knew the road and could teach them amaNdebele customs and language.

The necessities of trekking, like three-legged pots varying in size from one to five gallons were added, another flat three-legged tray for baking bread, coffee grinders, kettles and a sausage machine, indispensable for meat scraps left over from game kills.

In addition they had four dogs; a liver and white pointer who became H’s constant companion and was good with birds, a half-breed mixture of retriever and mastiff who was a great pal but no good for shooting, a half-breed bulldog a very strong dog and a terrier of sorts devoted to the cook and eating named ‘scoff dog.’

From Among the Matabele: Rev Carnegie’s wagon crew

The journey begins from Kimberley, but without Arthur Vaughn-Williams

They were ready to start on 3 May 1889, but had been to the opera the night before, where Arthur had become very friendly with the leading lady and only returned very late to the hotel! Next day he told his young brother H to make a start with the wagons and he would follow along some days later in the quicker Cape cart and four horses they had also purchased!

The drivers cracked their whips and the leaders brought the oxen up at a trot. Then to put the two spans of oxen into their correct places! First, they have a noose of a riem put over their horns before being sorted into their arranged pairs; two strong after or hind oxen for the disselboom and two clever oxen to lead as they guide the span and keep the wagon on the track. Next in importance are the vooragter oxen in front of the hind oxen, then beginning from the back, the other ten oxen are filled in. They are taken in pairs and tied to their places on the chain and the inspanning begins. First the pole and its yoke are lifted and placed on the neck of the after offside ox with yoke skeys, one on each side. Twisted reims are passed under the neck and the noose fitted into a notch on the nearside skey, but woe betide you if the ox shook its head and a horn caught you! The others were then inspanned as quickly as possible.

Each ox was individually named, there was much shouting with a fusillade of whip cracks and more extraordinary noises from the drivers, before the oxen pulled off and the wagons moved and after saying goodbye to Arthur, H followed on his pony. That afternoon they only travelled about eight miles (13 km) just to settle down the spans and outspanned before sundown and were turned out to graze. There had been some good rain in April and the grass was good.

George and H made some food; they had half a sheep and fresh bread, but no airtight tin to keep the latter and it soon went stale. The drivers and others kept a noisy conversation by the fire; H went to bed and read by candle-light, they had a good store of novels and some were later exchanged with other travellers. His shotgun and .577/450 Martin-Henry rifle were slung in loops inside the tent, a bag of cartridges hanging nearby, all his clothes below the kartel.

Travelling by ox-wagon

Oxen pulling a wagon load of four ton would travel at about two and a half miles per hour (4 km) on a good track. H writes the drivers rarely struck the oxen with their whips except when they were lazy; just brandishing the whip and calling the ox’s name was generally enough. The after or hind oxen might be encouraged by a dig in the ribs with the butt end of the whip. H says it was cruel to watch the oxen being whipped and this was more frequent when they were thinner and weaker and had less strength. He protested to the drivers on occasion and they looked at him as though he was mad.

There are two golden rules to trekking; outspan at least half an hour before sunrise and about an hour before sunset and turn your oxen out to graze. To prevent them becoming exhausted the rule was three treks in twenty-four hours of about three and a half hours each was generally enough for the oxen. The hours being from 2 – 6am, 9 - 12 noon and either 2 – 5pm or 6 – 9pm in the evening. They covered about twenty miles (32 km) a day in this way and the oxen had a chance to feed and rest. If there was no water or grass, this could vary considerably. A little water was carried in two half-barrels called water vaatjes under the wagons. A trek was sometimes called a ‘scoff.’

The first day trekking H tried using the whip, but only succeeded in getting it wrapped around his legs and the voorslag gave him such a stinging smack in the face that he never forgot it! The wagons had started at 2am whilst H was still in bed. As he was surplus to requirements he took his shotgun and shot a hare and a couple of khorhaan.[vi] H generally had eggs and bacon for breakfast, mutton, if available, cooked on a gridiron over the ashes with potatoes for lunch and a can of fruit. The shooting pony ran away the second day and returned to its stable at Kimberley. They were promised a refund of their £30 but never received it.

Most days H walked in big half-circles in the bush and re-joined the wagons some miles ahead, but often he saw nothing. The weather in May was perfect, just a little cold in the early mornings. The fine dust kicked up by the oxen rose high in the air and was a good indicator of the wagons’ location. On trek the cooking pots were slung onto the rails of the buckboards which ran the length of the wagons. He says on soft roads it was very pleasant sitting on the wagon box[vii] and even lying on the kartel to sleep, but if the going was rough with stones and tree stumps, it was ghastly and one simply got off rathe than being shaken to pieces.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: White-backed vulture (Gyps africanus) the most common in Africa

The country north of Kimberley

The north of Kimberley was most uninteresting, flat and scrubby with not a tree in sight as they had been cut down for the mines. The Vaal was crossed near Fourteen Streams, the drift fairly steep and they outspanned before the sun rose. There were kopjes and stony ridges here and there and isolated farmhouses some way off the road. A few wagons were passed and greetings exchanged; most of the time H was reading, smoking, learning a little Dutch from phrase books. He learnt quite a bit of the Dutch language from the two youngsters from the Cape but says many of their expressions were not fit for polite society!

Five days out of Kimberley the younger driver named Paul absconded taking a bag of Boer meal and it appears that some of Khama’s people they met had frightened him with stories about the amaNdebele.

Ninety miles (145 km) from Kimberley they reached Taungs, a tiny village of corrugated iron with a Major as magistrate before continuing trekking to Vryburg another forty-five miles (72 km) further on. He says the Boers they met were mostly of a very poor class and lived in two-roomed dried brick houses, the parents in one room and up to eight or ten children living together in the other room. Their windows were small, about a foot square, everyone went to bed soon after dark with the bush used as a lavatory. The only book in the house was usually the Bible. He says the men were well built and strong, but did little work, spending much of their time sitting on the stoep (verandah) and drinking coffee.

They cultivated small plots of land with mealies, corn and pumpkins, enough to keep them alive and to exchange at the nearest store for coffee, sugar, tobacco, or other necessities. Sometimes they grew their own tobacco, vile black, damp stuff that smelt foul. They were wonderful rifle shots and kept themselves in meat that way making biltong. A Boer could travel for days with a little biltong and dried biscuit, bread and coffee. They were mostly ill-mannered and surly to us English especially near Vryburg where their proposed Stellaland Republic had been nipped in the bud by the 1885 Warren Expedition. H says in later years he met many charming and cultured Boers who became friends including Generals Smuts and Botha and Denys Reitz.

Vryburg was a little bigger than Taungs, a few corrugated iron houses and huts and a biggish native population.

They trek towards Mafeking

Mafeking was seventy miles (113 km) from Vryburg and the country gradually became more interesting as they went north. Firewood was still scarce and dried cattle dung was their main source; it burnt hot but produced an acrid, unpleasant smoke and was called ‘mist.’ The nights were chilly and H was glad to sit by the fire after supper, but the smoke was perverse and followed one around making the eyes smart and necessitating frequent changes of position!

Outside a place called Setlagoli they saw what looked like mules, but H was assured were hartebeest. He took out one of the drivers and his Martini-Henry .450/577 and stalked them for several hundred yards before firing and seeing a young bull go down on its knees and fall dead a few hundred yards on before being skinned, cut up and the meat carried back.

The wagon track they travelled on was very poor, never repaired or improved; if a stretch became too bad, the wagon drivers just made a detour to avoid it. There were stretches with only thorn bushes for miles and miles, several rivers were crossed, full of sand and no water and sometimes the wheels sank in the sand to the axles and a double span was necessary to pull out, even offloading: a hard and tiring job.

Boulders at night were a nightmare for anyone trying to sleep; without springs the sleeper would be hurled out of bed and thrown against the wooden tent supports. Then the wagon would come off the boulder and they hit the other side of the tent!

H says that at native villages he often tried to get milk and fresh vegetables. Their huts were built of mud on a wooden frame and were beautifully round and plastered quite smooth and thatched with tambouki grass, a long hard grass that is better than rye for thatching. The outside walls were often painted in red or blue and were very neat and clean with a depression in the hard mud floor for a fire, but the smoke was dreadful. The people were very friendly, but shy.

They had trekked two hundred miles (322 km) in sixteen days over dreadful roads, lost a driver, a bag of Boer meal and a good pony. On the other hand H had learnt a lot about oxen, inspanning and driving and kept the servants in meat.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: helmeted guinea fowl is common throughout the region

They reach Mafeking

Just outside Mafeking they were caught up by Arthur in his Cape cart and four horses and a companion named Balane (pronounced Blane) Arthur had damaged his knee when the cart turned over and it was very swollen and sore. He told me the accident took place while Maund was passing him in another Cape cart at a gallop and swore that Maund was the cause of it. He had not even stopped to see if Arthur was hurt. H thought the ‘Lady of the Opera’ had something to do with it as Maund was also keen on her, but they were a queer, jealous lot of men that came and went to and from Lobengula’s country in those days.

Balane was originally from the Cape and spent many years hunting and trading all over Damaraland, Ovamboland and Namaqualand for oxen, ivory and ostrich feathers. He also trekked cattle from north of Lake Ngami to Kimberley where they were sold. Once there they generally blew all their savings in riotous living over six months! He quickly taught H how to make excellent scones and even bread on a gridiron over the ashes of a fire.

Mafeking was a miserable little dorp really, with a few corrugated iron houses, a hotel and a couple of stores, one belonging to Weil Bros.[viii] On a rise nearby camped under canvas were a contingent of Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP) under the command of Colonel Sir Frederick Carrington. During the four or five days that H was at Mafeking he met Gosling, Holt, Fiennes and Goold-Adams, all who would feature in later events.

Trek to the Limpopo river, passing Ramoutsa and Gaberones villages

They decided to get to Shoshong (also known as Mangwato) Khama’s capital, via Ramoutsa and the Crocodile River. The first day they made a long trek reaching bush country with good grazing. The oxen were always sent out to graze about an hour before sundown. And the two leader left the oxen in the bush and came back to the camp to eat. Sometime later, when it was dark, they came running in to say the oxen had all disappeared and although they had searched everywhere, could find no trace of them. Balane and H went out on horseback but saw nothing and all they could do was go to bed and rise at dawn to have another search.

When they got back they found Arthur talking to “a very queer customer adorned with bladders, dead frogs, lizards and all sorts of funny things round his neck and body.” Arthur said he would pay a reward if the oxen were brought in. “He had a very dirty bag, made of skin slung around his neck, and from this he produced several knuckle bones which looked decidedly human. These he threw in a rough half-circle in front of him making queer noises that sounded like incantations. He did this three times, mumbling away to himself, then, after long, deep thought, pronounced what H presumed he thought was in a supernatural voice, his judgement…If the boys were sent out alone with no white men, to a place where the sun set and they walked for four hours, they would find the oxen, all grazing peacefully in a glade. But if a white man went with them, the oxen would not be there.” And so it turned out and the oxen were returned!

The trek continued over dry and uninteresting country with a lot of wag-’n-bietjie (wait-a-bit) thorn bushes and the native kraals of Ramathlabana, Pitsani, Ramoutsa and Gaberones, the first and last having about twelve thousand inhabitants each. Most of the men wore skins of wild animals, which hung from their left shoulders, some had European hats adorned with feathers and they usually wore sandals. The women were more scantily dressed being naked above the waist with a skirt or kirtle reaching to below their knees. Blue and white bead necklaces were the usual adornments with occasional copper anklets and many had their faces tattooed. The men rarely carried any weapons, except sticks or knobkerries, hardly any guns. They must have done a lot of hunting judging from the skins they possessed and H bought a jackal skin kaross were about £2 which kept him wonderfully warm at night.

H had fair shooting with his shotgun, getting redwing, greywing, shrimpje partridges and red-legged pheasant (francolin) plus korhaan and guinea-fowl. At waterholes great flights of Namaqua partridges would come to drink in their thousands and they were good eating.

The grazing improved greatly as they approached the Crocodile river[ix] and there was more wildlife. At an outspan near the Crocodile there was a tremendous commotion when their dogs were attacked by baboons…the half-breed bull dog received a bad bite behind the neck, the half-breed mastiff was dead, but the terrier, the pointer Grouse and the retriever were unhurt.

They reached the junction of the Crocodile with the Notwane river, a lovely spot where the river ran deep about a hundred yards across (90 m) and they swam in a pool which was first beaten with sticks to drive away any crocs. They were now three hundred and fifty miles from Kimberley (560 km) and needed Khama’s permission to travel further. Arthur went to Shoshong fifty miles (80 km) north west of their present position. Now they had water to bath in and drink freely; it being scarce before and Balane had taught H to ‘bath’ in a ‘tea cup.’[x] Fleas and flies were a constant menace; a tin of condensed milk or jam would be almost instantly covered with a swarm. Keatings flea powder had to be used every night on the blankets.

Victorian advert for Keatings Powder

As Balane slept in blankets always feet to the fire, H began to do the same and gave up sleeping in the wagon, except when lions were troublesome. A woolly cap was a necessity as the nights were very cold sometimes freezing the hair to the pillow and the water in canvas water-bags froze solid.

The Crocodile river had provided plenty of game including wild geese, teal, duck, guinea fowl and pheasants.

Arthur sees Khama, they meet Ericksen, wonderful shooting on the Limpopo river

The evening after Arthur left for Shoshong they heard cattle lowing a mile or two away, so Balane and H walked in that direction to see what it was all about and found a camp on the river with a man named Ericksen and his companion, Damara, son of a king of the Damaras, with twelve hundred oxen they were taking from Damaraland past Lake Ngami to Kimberley where they were expected to sell for £12 each. Ericksen and Balane were old friends and swapped many stories which were most interesting. We decided to bring our camp nearer to Ericksen's next day, both were keen on whist and we played every evening from dusk until late at night.

They explained their hunting technique for wild ostriches, a good cock-bird’s plumes were worth £45. Apparently a sighted ostrich always streaked away in a big circle and by keeping a pony on an inner track the ostrich gradually became exhausted and ran until they dropped and none of the valuable feathers were damaged.

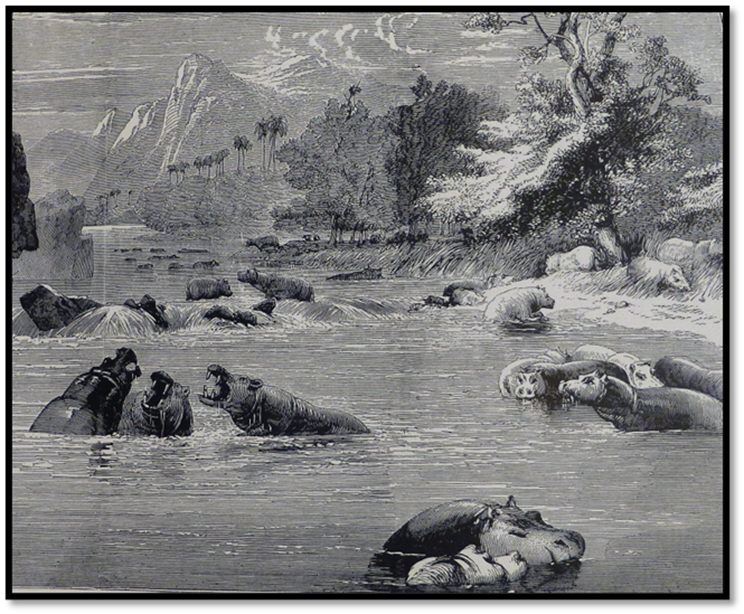

They were sorry to leave their new companions, but soon the oxen were well rested on the good grazing. They trekked alongside the Limpopo River for two or three days to where another river joined (Bonwapitse?) and camped at a beautiful spot with big trees where they were to meet Arthur. Here H met for the first time the ‘Go-away’ bird, a most irritating little fellow that sat on the top of tall trees and frequently warned the game that he was trying to stalk. Despite this he had the best shooting day ever in his life with a bag of 135 birds including geese, teal, duck, guineafowl, bush pheasants, partridges and Franklin. The skin of a blue monkey was later given to Lobengula.

From Pioneers of Rhodesia: hippo on the Limpopo river

All the game meat was cooked and then put through the sausage machine, mixed with allspice and put in tins and jars that were covered in lard and fat and kept as potted meat. A hunter’s pot was always kept stewing on the fire and any odd birds or pieces of meat went into it. If you came in late there was always the camp stew ready for eating and was excellent to taste. ‘Doughboys’ made of meal and baking powder were stewed in the same pot which was slung on the wagon with the lid tied on with reimpjes[xi] and only cleaned out every few weeks.

H also got his revenge on the baboons for killing the dogs as the dominant baboon sat still and received a bullet through him. Many evenings they watched the animals coming down to drink at the river – waterbuck, kudu, reedbuck, zebra and sometimes giraffes.

Journey to Shoshong where they meet Khama; travel on bad roads, joined by San Khoisan; most of the servants desert, Arthur leaves for Lobengula’s kraal

Snakes were a great nuisance, before settling into a camp the drivers would strike the trees with their long whips and occasionally a Boomslang would tumble down. One day H encountered the dreaded black mamba on the path travelling at great pace towards him but pulled himself aside and the snake passed on. Scorpions and centipedes were also a nuisance and were often found under logs; a scorpion bite being like a streak of fire through your body.

A mile from the river the trees thinned out considerably, the sand rivers easily crossed at drifts and Shoshong or Mangwato reached after three days. Arthur took H for a tour of the village that had no stockade around it and the huts were built square instead of the usual round design. They went into Khama’s courtyard and he came out and offered them coffee. He was a fair height with a small moustache and dressed in European clothes, a smart ‘wideawake’ hat and blue spotted food puggaree, which was worn in those days. Beer (outualla) was completely outlawed in the country with many spies who reported anyone making it. They had been warned beforehand not to let any sign of alcohol be seen on their wagons as Khama was a strict teetotaller and would not even allow it to go through his country if he knew about it.

Shoshong was very evil smelling as sanitation was sadly lacking and people just used the bush as a toilet. They were told that many inhabitants were migrating to Palapye as it had plenty of water and saw many wagons leaving loaded with families and their belongings, including thatching and poles for their new kraal. A few days into their trek they saw the old town of Shoshong going up in flames. It had once housed forty thousand people, but the poor sanitary conditions resulted in widespread enteric fever.

Khama insisted on sending a petty chief as guide with them, much against their will, as he would act as a spy and might report that they were carrying alcohol. They had to take him whether they liked it or not. After a few days Shoshong was left and they headed for a long stretch of desert and bush between Shoshong and the border of Matabeleland at Francistown and Tati. Their oxen were in good condition but they saw many in poorly and cruelly treated on the road to Palapye before they branched away to the east.

The road was badly worn by wagon traffic, there was a stretch of two or three miles where it felt like going down rocky stairs with drops of a couple of feet that was very hard on the wagons and oxen. The rivers were all sand, no water and ran east to join the Limpopo river. 1899 was remembered as a very bad drought year.

At the second outspan, fifteen miles from Shoshong (24 km) two San Khoisan hunters joined the camp fire who said they wanted to travel with them. The guide insisted they were Khama’s slaves and must be sent to Palapye, but he was laughed at. Arthur saying: “your chief is a christian. How can he keep slaves.” The guide disappeared during the night but caused trouble later on.

The roads continued bad and by the time they reached the Chakane Pool mentioned by Robert Moffat, a number of oxen had been lost, some from the dreaded lung disease and with only twenty-eight oxen left it was decided to give them a good rest. The skins of the oxen that died were stretched tightly over the front part of the wagon hoods and protected them from overhanging tree branches that were frequently met. Others were cut into long strips and made into reims. They were rubbed with fat and then slung in loops over the branch of a tree with a heavy stone hung on the bottom of the loops and a pole pushed through the lower loops and twisted round and round. When the pole was withdrawn, the strips became untwisted and this continued until they became quite supple and is called ‘braying.’ They were then cut into lengths of twelve feet (3.7 m) and used to replace worn out reims.

On the trek they met a wagon coming from Tati with a white man who said he had been turned back north of Tati and that if they did get in their lives would be in danger from Lobengula’s young warriors (majakas) who were extremely restless and pressuring the king not to allow any more white men into the country. Arthur was not over worried, but the man’s servants put the fear of death into our own servants and they cleared off that night excepting George, the amaNdebele, the two leaders from the Cape and Arthur’s Cape cart driver. Now they were short of oxen and men; it meant George, Balane and H had to drive the two wagons.

Arthur decided to leave for Gubulawayo immediately and he and his driver took a horse and a spare each and some provisions and a blanket. They would ride to Tati first, a journey of 250 miles (400 km) where he had a letter to Sam Edwards[xii] who was in charge of the Tati Concession and gold mine.

Khama’s men take one of the San Khoisan hunters, they journey to the Macloutsie river through the Thirst land and lose more oxen

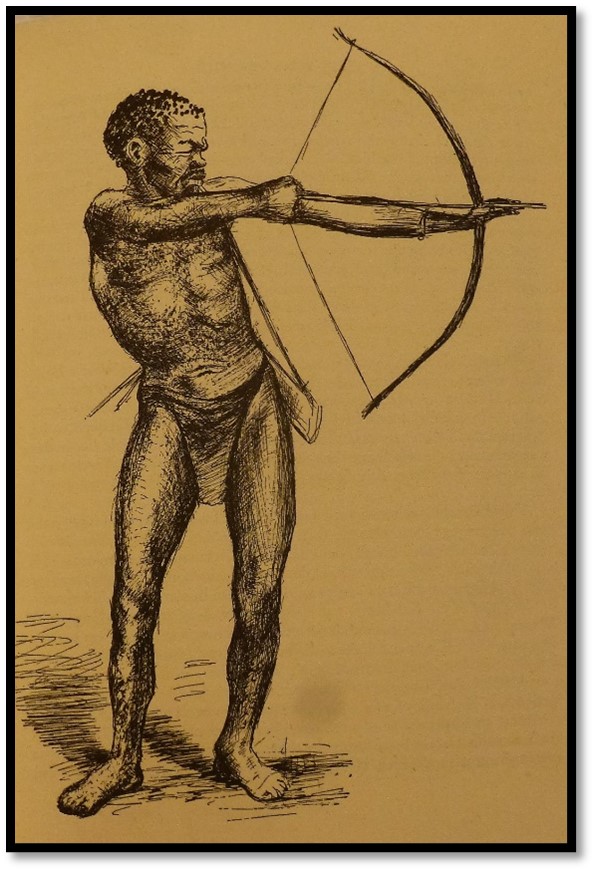

H describes a San Khoisan camp he came across whilst out hunting, he noticed the bones lying around before he saw their small shelters. They only stay in one place as long as there is game and water. The men all had sores around their ankles as they make such tiny fires to avoid giving away their camp that they sit right on top of them to keep warm and suffer from chronic burns. All the men and boys carried small bows, just two and a half feet long (75 cm) with six to eight arrows with iron barbs in a quiver made of bark, all smeared with a gummy looking poison.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: San Khoisan hunter

Their water was carried in ostrich egg shells tied on the end of sticks. They stalked the game in hunting parties of three or four, a buck struck by a poisoned arrow would be followed for hours before it dropped. Their diet comprised meat supplemented by every form of edible berry, bulb and root. The absence of water never seemed to worry them much, they could exist on the juice from wild melons and they knew secret water holes where they pushed a long reed deep into the sand and sucked it up.

Returning from hunting one day with one of the San hunters H heard a great commotion from their camp

and found that four of Khama’s men were sjamboking the other San hunter unmercifully. When H threatened to shoot them if they failed to stop, they dragged their victim away, the other San hunter had wisely disappeared. After this trouble with Khama’s men, which had probably been instigated by their guide when he returned to Shoshong, they decided to move on quickly to the Macloutsie river.

This trek entailed crossing sixty-five miles (105 km) of waterless bush. Every available utensil was filled with water and the three wagons (including Greef’s) after watering the oxen well, set off after sundown in order to get two treks in before the sun came up. The first trek from 5:30 – 10pm and the second from 2-6am. The country was bleak and dreary, white tree skeletons dotted here and there rising from the thorn bush and little sign of game. H lost his way in the bush, cooed for all he was worth, then fired three shots – a signal for help - and heard one in response in a very different direction from where he was going and made it back to camp. This was a powerful lesson in how easy it is to get disorientated in the bush.

The oxen could smell the water in camp and the weaker ones were given some from a bucket. The grass had no moisture in it. At sundown they inspanned again and continued, the track in poor condition with Balane and H driving one wagon, George in the other. They were now in lion territory and needed to make sure the oxen did not stray. They trekked again at 2am until sunrise, in the two days covering about fifty miles (80 km) and next day saw a patch of green grass. One of the voorloopers confirmed there was water, so the vaatjes (barrels) were taken to fill them up before the oxen stirred up the mud. George and Greef’s voorlooper were left with whips to keep the oxen back, but alas they could not and the oxen smelt the water and stampeded into it.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: lioness

Nothing would stop them and some drank so much that seven lay down and were drowned, a heart-rending sight. This was bad news, as they now had only seventeen oxen, really only enough for one span and they were in weak condition. The water was too churned up now for human consumption. The only way to get along was to inspan the oxen on one wagon, do half a trek and then send them back for the other wagon. It was dreary and tiring work, but all they could do for several days in order to reach the Macloutsie river.

The bush was now getting thicker with occasional Baobab trees. One day they came across a small camp of natives who told them an earlier traveller named Campbell had lost his white companion when he went hunting and still had not been found. As they had to rest the oxen, H, Balane and the San hunter went searching for the lost man, the San hunter picking up a spoor that the others could not see. After following the spoor for about ten miles they came to a small pool of brackish water and saw nearby, a hat and shotgun and lion spoor. It was clear the man had been killed by lions.

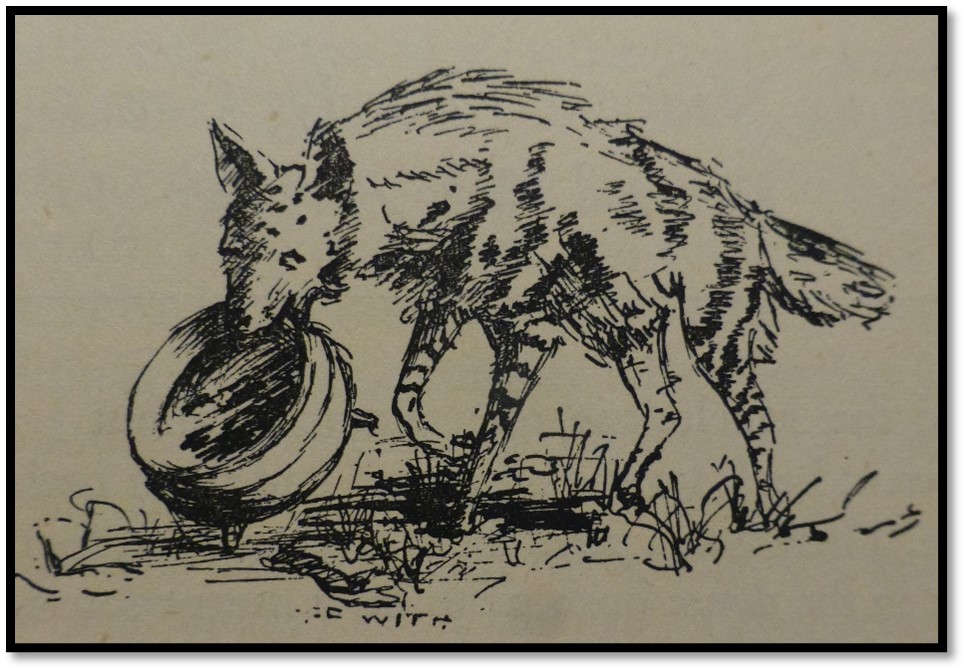

Lions could be heard at night grunting and roaring in the distance and it was essential the oxen were herded into a scherm made of thick wag-’n-bietjie thorn bush every evening. Usually they found one made by a previous traveller and patched it up. The yap, yap, yap of jackals and the long drawn out eerie howls of hyena were often heard, as was the cough of leopards too. Hyena are fond of ox reims, which have a salty taste or even a saddle left lying around. One night a pot was left near the fire with food in it, next morning it was gone without a sound and the San hunter found it several hundred yards away. Only the San hunter dared venture out of the scherm at night, the others too afraid.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: a hyena takes the hunters pot

They trekked on slowly towards the Macloutsie river with the bush always getting thicker and dense right up to the wagon track; there were huge flocks of guinea fowl, sometimes flocks of three hundred and H says they ran through the grass like hares. Greef in his light wagon went on ahead to try and get in touch with Arthur and send them more oxen. H says Greef spent his life in his wagon and camping and only worried if he ran out of coffee, tea or milk!

They reach the Macloutsie river; big game is plentiful with lion and kudu

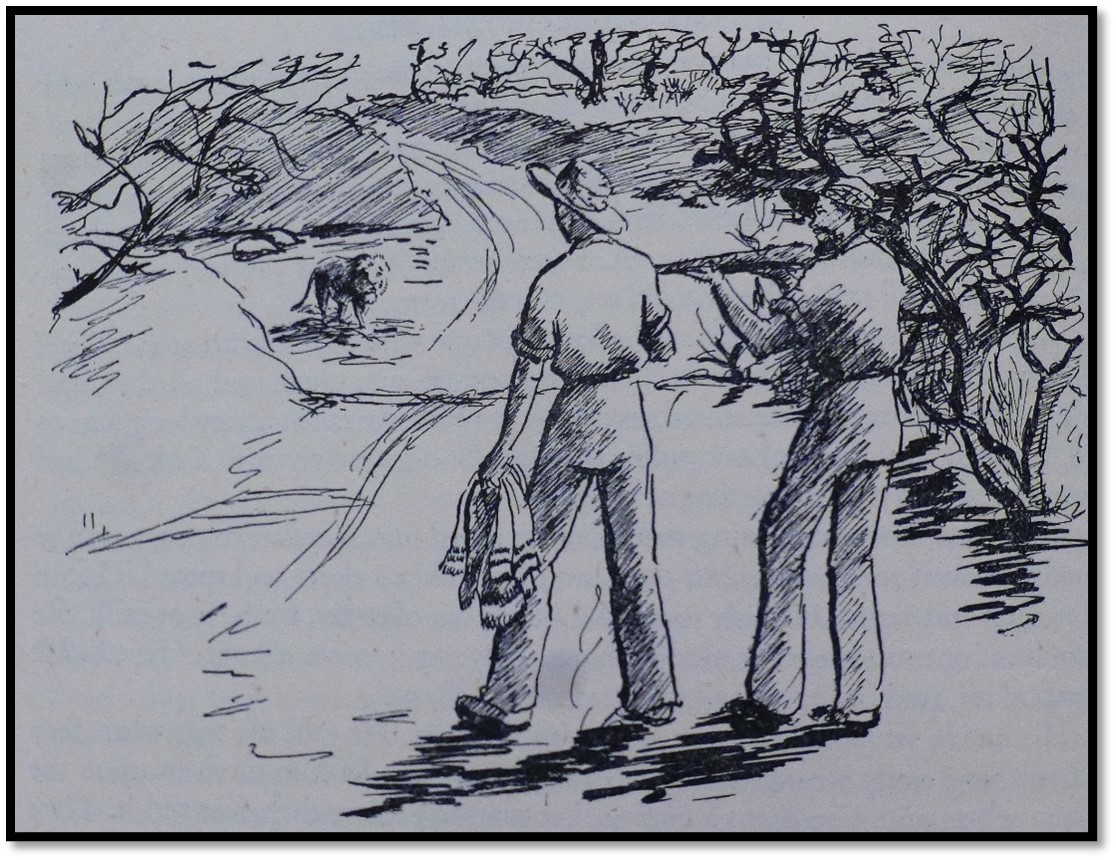

They reached the Macloutsie in the late afternoon. There was a good thorn scherm ready for the oxen and the voorloopers were given strict instructions not to let them out of sight. The sandy river below was about 300 yards wide (275 m) and they knew there was water if a hole was scraped a couple of feet deep in the sand. H suggested they go down and have a bath, which was badly needed. Balane suggested bringing the shotgun to scare off any lions. H laughed, but fetched it, putting bird shot in the plain bore and buckshot in the choke bore and off they went with the retriever dog. They had gone only seventy yards when the dog made a devil of a noise barking into the thick bush and they heard a growl. Balane said “Lions!”

Just as they got behind a wag-’n-bietjie bush a large kudu cow rushed past not four yards away, crossed the road and disappeared with the dog after it. They followed the dog across the road and there, just below, not eighty yards away in the sandy riverbed stood a lion, a big black maned fellow. Without thinking, Balane fired the barrel of buckshot. The shot spat up sand all around the lion. He was very angry and growling and lashing his tail, but slowly moved off across the river, looking back every now and then, to see where we were.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: a black maned lion in the Macloutsie riverbed

The servants, hearing the noise, came to see what happened. They collected their rifles and the San hunter and followed the kudu’s spoor until it was found a mile off lying dead. It was now late in the afternoon so it was cut up and carried home. There were huge gashes on its back and rump where the lion had evidently landed on it with its claws and then slipped off. The voorloopers with all the excitement had left the oxen. They all had to go off into the bush to hunt for them, luckily it was a moonlight night, but even then it took two hours to find them all.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: a female kudu attacked by a lion

Balane said with all the kudu meat the lions were sure to come around that night and they went to bed with loaded rifles. After 10 pm the dogs began to bark and it went on all night with the lion’s shadowy forms in the bush. They roared occasionally to try and stampede the cattle but Balane and H had taken turns to guard and sleep and the lions cleared off by dawn.

The thick and thorny bush did much damage to their clothes and stuck into their thighs, knees and back of hands. H says it was many years before he got rid of the little black marks, hundreds of them, left in his hands and knees!

Arthur sends oxen and they reach Tati: Sam Edwards accompanies them past Mangwe Pass

After a few days twelve oxen arrived at the Macloutsie river from Arthur and three servants, one a driver. They reported that two mail runners had been killed by lions just a few miles on. The steep banks of the Macloutsie required full brakes on the wagons and stones under the wheels to prevent the hind oxen being crushed by a runaway wagon. In the sand the wagons sunk up to their axles, double spans were required and the sand dug away with skeys and yokes being broken; it took several hours to cross the three hundred yards and the oxen needed resting on the far bank.

Africana Museum, Johannesburg: Will Tainton, G.A. Phillips, Sam Edwards, Cornelius van Rooyen

The Shashe river, about 15 miles away (24 km) was reached that night with the last section in the dark. H was sitting on the front of the leading wagon when a lion growled and both spans took fright and swung round and tried to break away. Apparently this is a common trick of theirs, but beyond a broken yolk skey nothing serious happened. Skeys and yokes could be made from local hardwood trees, disselbooms also.

Early next morning H went down to the river that was about four hundred yards (365 m) of deep sand and dry, but during the floods can rise thirty feet (9 m) They rested that day and next morning got across the Shashe which was as bad, if not worse, than the Macloutsie. The Tati river was a further 14 miles (23 km) further on. This part of the country was called “the disputed territory” as neither the amaNdebele nor the Bechuanas could really lay claim to it.

The Tati river was even wider, about five hundred yards (460 m) and they outspanned on the far bank and sent a messenger to Arthur at Tati where he was staying with Sam Edwards awaiting our arrival. He rode over and helped them across the sandy bed. His trip to see Lobengula gone well, Colenbrander had been a great help and they were allowed to enter Matabeleland providing they did not look for stones, meaning gold.

The wagons were double-spanned to cross the sandy Tati river and outspanned near the store where Edwards lived. They visited the mine which had a steam engine and crushing plant,[xiii] but all the miners were down with malaria that was particularly bad in these parts.

Two more oxen had died at Tati. They were able to buy a few untrained ones but had a devil of a time training them. The method was very crude, they were driven round and round in circles until they were tired, when a couple of reims were put over their horns with a voorloper either side. They kicked and bucked all over the place, but after two or three days became more amenable and they were able to inspan them with the older, quieter oxen.

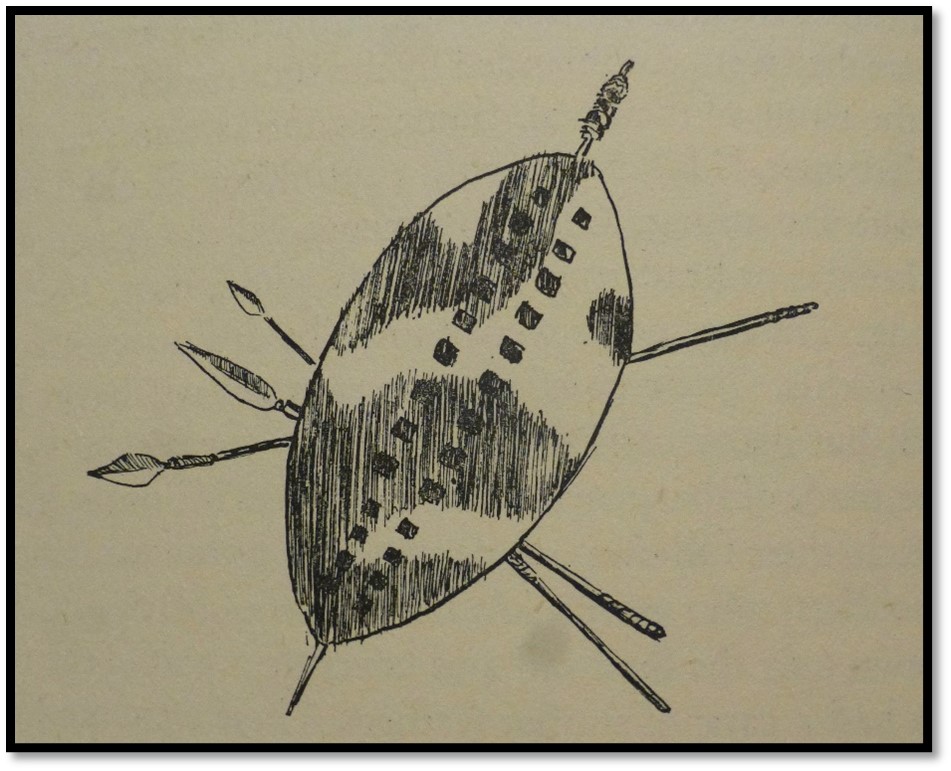

Edwards said he would accompany them through the Mangwe Pass and they left next day on a very bad rocky road and outspanned just below the Pass watched all the way by amaNdebele scouts on the tops of the hills, but they evidently had word not to molest us. The induna came down and talked to us saying his name was Buffel, meaning Buffalo. He was a fine looking fellow, very well built and dressed in a moocha with the ring and oval feather headdress made of guinea fowl feathers. He carried the short broad bladed stabbing assegai and a longer, slender throwing one. We gave him food and then traded for chickens and eggs at a small Makalaka[xiv] kraal.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: amaNdebele shield and assegais

Buffel challenged H to a race – H wanted to do 440 yards, Buffel suggested a hill about three miles away! H says he was leading at 400 yards but beaten at the finish with Buffel not even out of breath! Sam Edwards now took his leave and walked back to Tati. H says they went on to the Ramaquaban river.[xv]

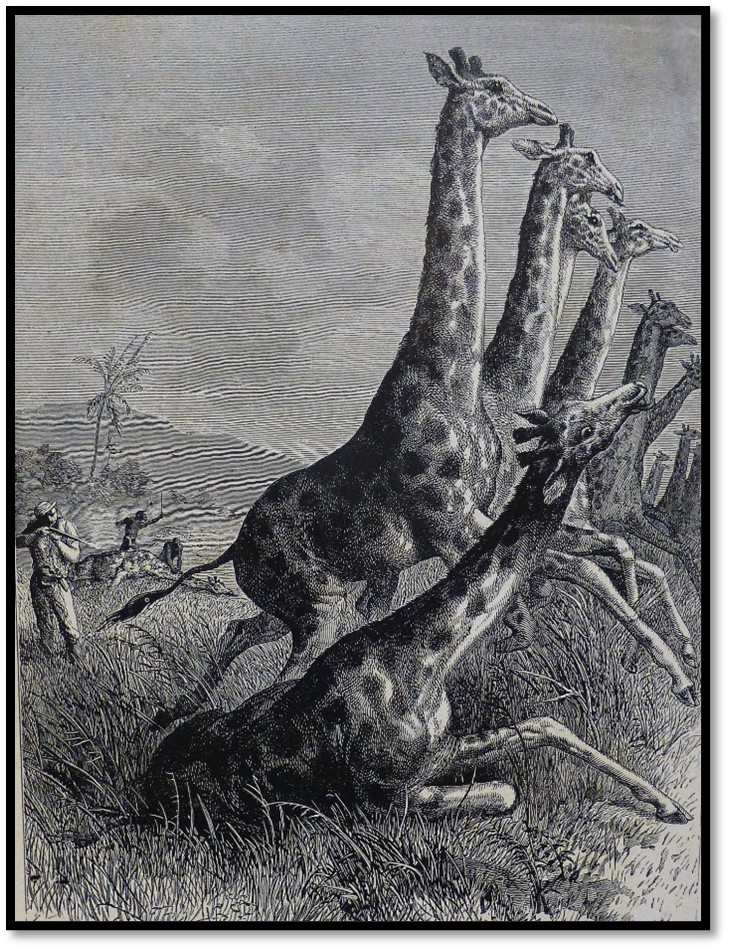

Their whips were worn out…Arthur asked H to shoot a giraffe and with the San hunter’s help he managed to stalk a giraffe and drop it. It took three hours to skin and cut up the animal. The meat is not good eating, but the bones contain marrow which is excellent. The skin was cut off and brayed with fat to cut several long whips and many reims.[xvi]

From Pioneers of Rhodesia: giraffe shooting

Their San hunter just disappeared one night much to H’s regret and was not seen again. Out hunting with a young amaNdebele they took on, H shot an antbear (aardvark) that disappeared into a hole under an antheap. It was dug out and weighed well over 100 lb (45 kg) The meat was not good, resembling tasteless pork, the Boers make saddles from their skins.

Arrive at Plumtree and meet Thomas McMaster; raided by amaNdebele before reaching Figtree

The Makalaka women mostly wore strings of beads in blue and white and a little beaded apron, six inches wide by three inches deep (15 x 8 cm) for decency and often followed the wagons for miles. H thought they stayed with the wagon for protection. He says he used to sit on the tail of the waggon and play his banjo much to the delight of these native followers.

On one of our treks two ‘Zambezi boys’ joined the cavalcade following us. They had been working on the Kimberley diamond mines and were returning with their fortune on their heads and backs including tin cans, mugs, saucepans and all sorts of things slung on their bodies. After following us for a while, they branched off to the west but had not gone far before half a dozen young amaNdebele soldiers (majakas) bore down on them. They had evidently been lying in wait for them and the Zambezi boys began to run. But the amaNdebele caught them and knocked them about with sticks and kerries and the pots and pans fell all over the place. The poor fellows only escaped with their lives because the majakas were busy collecting their spoils. H was furious but could do nothing about it and heard later it was a very common occurrence. They were repeatedly warned by Sam Edwards not to interfere in any way with these majakas; they were very truculent and out for trouble.

They were surprised when two white Catholic priests walked into camp from their Mission a few miles away in the bush (in 1887 the Catholics established Old Empandeni Mission seven km south-south-east of present-day Empandeni Mission – see appendix 3 of the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The countryside became more and more hilly as they entered the Matobo hills with their rugged, jagged looking tops. They form the watershed for the rivers running south to the Limpopo and north to the Zambezi rivers. They met John Lee who lived a quiet and retiring life and also Thomas McMaster, his son-in-law, who carried out trading and hunting in Matabeleland. McMaster’s old shooting boy had suffered a serious accident when a cartridge in a double barrelled rifle had gone off in the breech and splinters had entered both eyes. H examined the man, but it was evident that both eyes were hopelessly damaged. McMaster said he was the best servant he ever had and he would look after him for the rest of his life.

They reached Plumtree and many young amaNdebele crowded around. They were very truculent and they only got rid of them by putting the fire out so they left looking very sulky and unpleasant. Later that evening, as they ate supper, there was a tremendous commotion with shouting and whooping. They ran into the bush to see a crowd of young majakas driving the oxen, goats and sheep away and brandishing their assegais. It was dark and nothing could be done. Luckily, the horses were tied to the wagons and not taken. In the morning Arthur sent his wagon boy and an induna on two horses with a letter to Colenbrander and a message to Lobengula for help.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: the oxen are stolen by Majakas

No more was seen of the majakas but they heard sounds of great rejoicing far into the night and a few days later an induna arrived from Gubulawayo who went straight to the kraal and made them return the oxen, but the sheep and goats had all been eaten.

The closer to Gubulawayo the nearer they were to the Matobo Hills and one day they outspanned half a mile from their base. H took his rifle alone to hunt for klipspringers but on his way up found the way barred by a big troop of baboons who jabbed and barked at him. He thought if he fired a shot at them it might frighten them away and although he only had four cartridges with him aimed at a big baboon. He heard appalling sounds behind it and may have hit one of the others. Four big baboons came clambering down the rocks towards him, so he bolted down the hill and it was a dreadful job among all the rocks and stones. He stopped and had another shot at them which put them off for a while but by the time he fired his last cartridge, they were getting close. Luckily those in camp had seen what was happening and came running out firing shots and shouting at the baboons until they cleared off and he left them severely alone after that!

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: H being chased by baboons

More than once when H went out alone with his shotgun after partridges in the Matobo hills he met small parties of young majakas. He thought they waylaid him because they would suddenly appear from behind a boulder, racing down at him with their ostrich feathers flying from their headgear and their long-haired goatskin garters and arm bands waving. They would race right up to him with their assegais pointing straight at him and all he could do was laugh. They would shout “How” and clear off again. It was, he thought, just done to frighten him and his fingers itched to put a dose of birdshot into their bare backsides.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: young majakas trying to intimidate H

At their outspans the natives brought bowls of pinkish red rice for barter. It was good eating and they used the coffee mill to grind it and make rice cakes, a welcome change. Tobacco was also brought in big cones about twelve inches wide and six inches high with a big hole in the middle. The natives used it for snuff and mixed it with ground-up aloe leaves.

They reached Figtree, so called because of the huge wild fig tree that grew there. It had a lot of fruit in season which baboons and monkeys were very fond of. The tree had the names and initials of Moffat, Livingstone, Selous and others cut into the bark and H added his own. They arrived at Gubulawayo on the evening of 4 August 1889. H’s stay at Umvutcha is in the article A Visit to Lobengula at the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha in 1889 – Lieut-Col. H. Vaughn-Williams recalls his stay after 57 years under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

References

H. Vaughn-Williams. A visit to Lobengula in 1889. Shuter and Shooter, Pietermaritzburg, 1946

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town 1966

D. Carnegie. Among the Matabele. The Religious Tract Society, London 1894

Notes

[i] Salting was done by taking a piece of the lung from an ox that had died of lung sickness, pushing a needle through it and then sticking the needle into the tail of healthy oxen to make them immune. Some died after inoculation, but mostly they lived although the inflammation might make the lower part of the tail fall off.

[ii] A shooting pony was trained to standstill when the reins are dropped on its neck to enable the rider to shoot whilst still in the saddle.

[iii] A Visit to Lobengula, P15

[iv] The killings relate to the two British emissaries, Captain R.R. Patterson and Lieut T.G. Sergeaunt annoyed Lobengula with indiscreet references to Nkulumane in Natal. Together with their guide Ewan Morgan Thomas and at least two servants they died from drinking poisoned water on 20 September 1878, whether by accident or deliberate murder was never determined. See the article Richard Frewen, the man who annoyed Lobengula and the consequent deaths of the Colonial government emissaries on their way to the Victoria Falls under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[v] The word Fingo comes from the word describing the Mfengu people, who like many others were scattered by the Zulus under Chaka during the Mfecane (the crushing, scattering) during the period 1810 -40 with many fleeing to the southwest of present-day Transkei in the Eastern Cape

[vi] The red-crested Khorhaan (Lophotis ruficrista) and were found quite commonly throughout Southern Africa

[vii] The wagon box on the front of each wagon was where the tools, such as spades, axes and spares were kept and was a convenient seat for the driver and often used as a table in camp

[viii] The Weil brothers, Julius and Sam, made a lot of money during the Boer War of 1899-1902 supplying oxen and wagons and supplies to the military

[ix] At the confluence of the Crocodile and Marico rivers, the name becomes the Limpopo river

[x] A mug holding half a pint was dripped onto the bathers head and so on down the body until you managed to wash all over. It sounds difficult, but it can be done!

[xi] Reimpjes are strips of hide

[xii] Sam Edwards first came to Tati with the London and Limpopo Mining Company in 1869 with Swinburne, Levert and Griete and then went through Inyati to the Umfuli (Mupfure) river. Swinburne left Tati in 1870 leaving Levert in charge. Levert and Elton were hurt by the dynamite explosion at Halfway Reef and Acutt became the manager before he was succeeded by Nelson in 1871. The company lost its concession in 1881 after failing to pay Lobengula its £30 annual rent. Lobengula granted Sam Edwards the concession for an annual £50 and he lived at Tati for the next ten years as managing director of the Northern Light Company and as Lobengula’s ‘immigration officer’ until his retirement in 1892.

[xiii] Arkle, an engineer had brought the steam engine with a team of 32 oxen as far as Inyati mission; the stamp mill was still being assembled in Natal under Levert. But he amaNdebele were fearful it was a device to take their land away and the steam engine had to be hauled back to Tati and with the stamp mill was used to crush quartz mined at Tati – amongst the first to be used in Southern Africa.

[xiv] Makalaka people were the original inhabitants of Matabeleland and cultivated their land and kept cattle, goats and sheep but were considered their subjects by the amaNdebele who arrived in the 1840’s

[xv] I am puzzled by H saying they went from the Mangwe Pass to the Ramaquaban river which is well to the west and forms the border between present-day Zimbabwe and Botswana

[xvi] Prior to their arrival Lobengula gave some Boers permission to shoot giraffe – their skin was in demand as engine belting on the Witwatersrand. Apparently they shot hundreds of giraffe and left their carcasses all over the veld. Lobengula was very angry and said no Boers would be allowed to shoot in his territories again

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: