Sandawana emeralds are amongst the most beautiful and sought after in the world

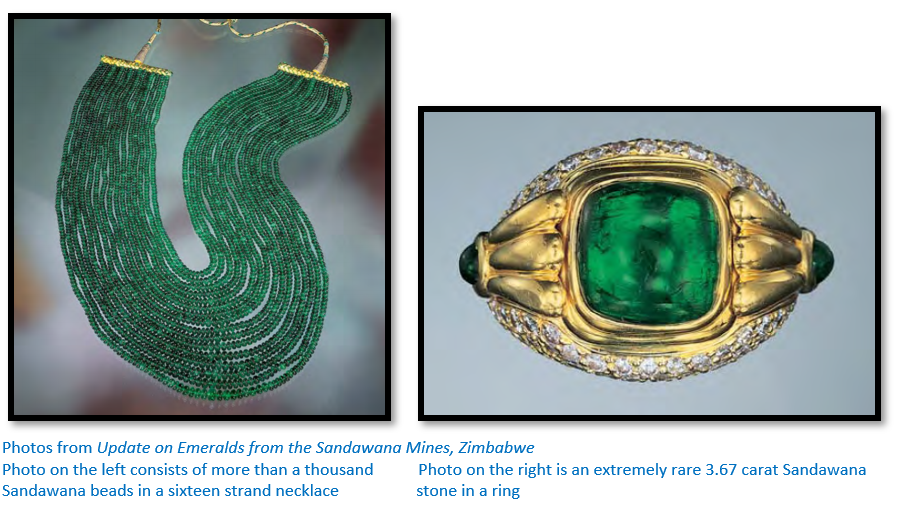

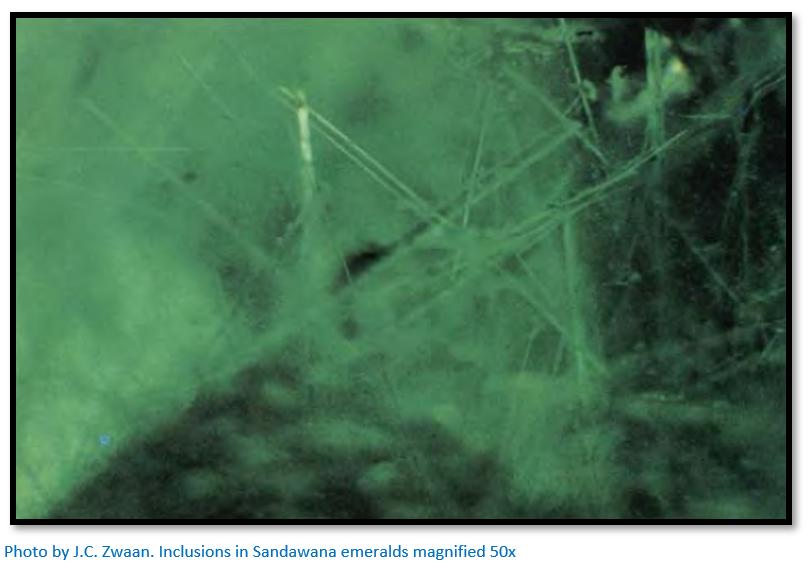

This article is based upon a number of articles listed in the reference section but most of the technical information and photos are from Update on Emeralds from the Sandawana Mines, Zimbabwe by J.C. Zwaan, J. Kanis and EJ. Petsch for which I express thanks.

Emerald is considered the birthstone of the month of May

The rich green colour symbolises spring and the symbol of rebirth and love.

Who discovered the Sandawana emerald deposit?

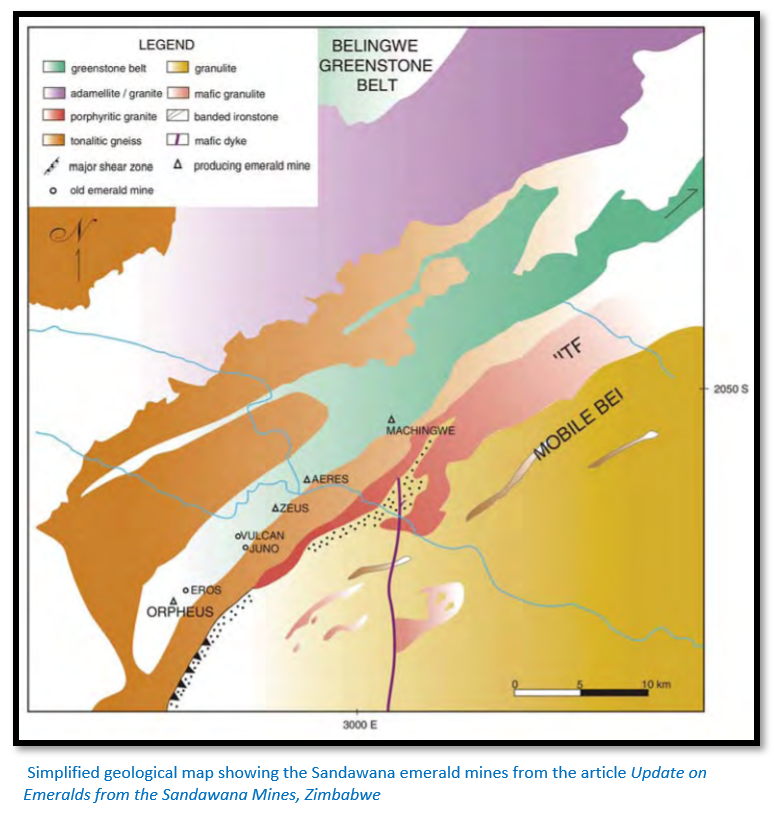

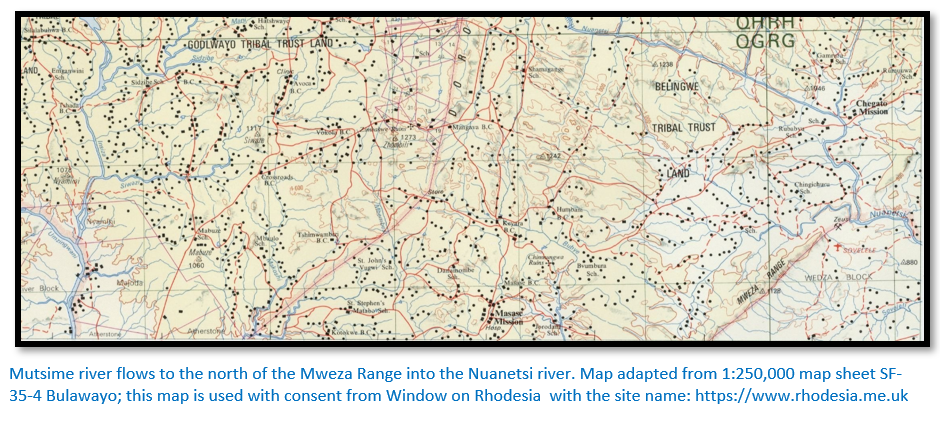

In the 1950’s the Southern Rhodesian government was offering financial incentives for discovering new deposits of beryllium and lithium minerals metals. In October 1956 two former civil servants who had resigned their posts to take up full-time prospecting, Laurence Contat and Cornelius Oosthuizen were searching for beryl and lithium deposits within the Belingwe, now Mberengwa district of Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe with their native prospectors who had the know-how to look for unusual rock formations.[i] They concentrated on a small area south of the Mweza Range which showed the most favourable geological conditions for the formation of large pegmatites.[ii]

Within ten days of arriving their prospectors had found several pegmatite deposits that indicated they were on the correct trail and seven months later after an intensive search they came across the high quality emerald producing Sandawana deposit situated in the contact zone of pegmatite and tremolite schist along the southern slope of Mweza Range.

This first stone was discovered about 5 kms west-southwest of the confluence of the Nuanetsi (now Mwenezi) and Mutsime Rivers. They called their first claim “Vulcan.” On 17 May 1957 after a rainstorm a Vulcan worker named Chivaro found a deep green crystal protruding from a muddy footpath, some 2.5 km northeast of what eventually became the Vulcan mine. He reported the find to his employers, who rewarded him handsomely. Follow-up at the spot, which would later become known as the Zeus mine, revealed the presence of more such crystals in the “black cotton” soil, the popular name for a dark calcareous soil.

They checked out their first finds with Dr Edward Gübelin, author of one of the articles cited below before revealing the discovery to government officials and seeking security protection.

The well-known A.E. Phaup of the Geological Survey Office at Gwelo, now Gweru confirmed that their first samples were gemstones. The Department of Mines was told of the find but little interest was shown by the Southern Rhodesian Government until news came that Contat and Oosthuizen had sold a batch of emeralds worth about $15,000 in New York. Then an ordinance was passed in February 1958 making all precious stones in Rhodesia subject to the same control regulations as those in South Africa. Initially rumours speculated about a diamond find, but it soon became clear that their find related to emeralds.

What is the origin of the name Sandawana?

According to the authors of the article[iii] the name Sandawana, which refers to the mining area and the emeralds mined there, originated with a mythical tale about a “red-haired animal.” According to local African folklore, possession of one of this animal’s red hairs would result in lifelong good fortune (Böhmke, 1982) Similarly, it was believed that possession of a Sandawana emerald should bring the owner good luck!

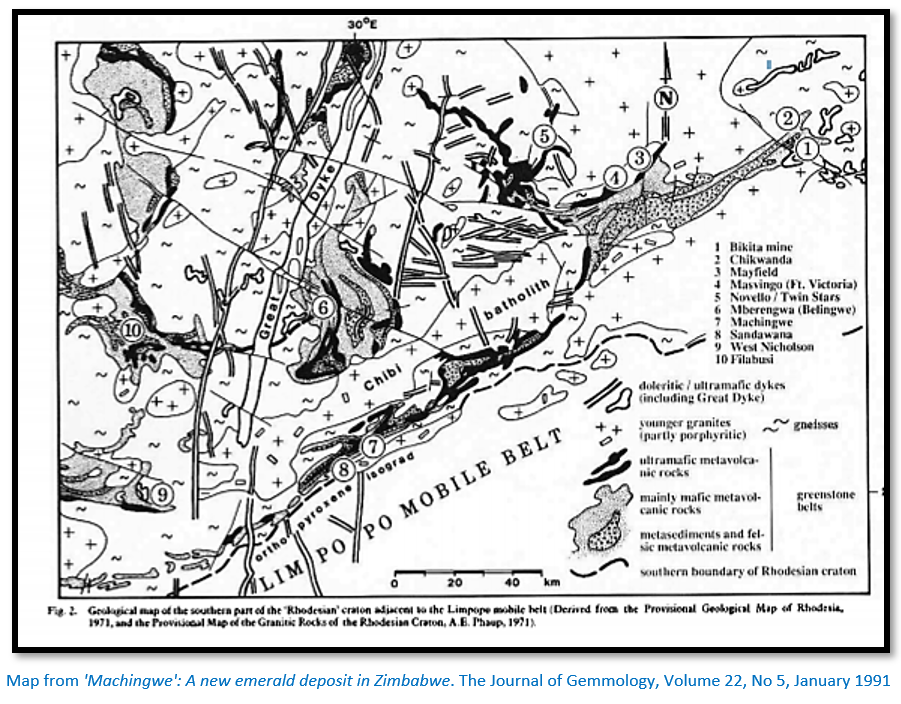

Are there other emerald deposits in Zimbabwe?

Yes, there are other locations where emeralds have been found including the Masvingo and Filabusi greenstone belts but the Zeus claims at Sandawana proved to be the most consistent deposit for high quality gemstones and has been by far the biggest producer with peak production in the 1950’s to 1960’s. The Machingwe claims approximately 12 kms north east of Sandawana in the Mweza range have also been producing since 1986.[iv]

Past and potential future owners of Sandawana Mine

The original emerald claim holders Laurence Contat and Cornelius Oosthuizen processed their emeralds by simply washing wheelbarrow loads of soil. By late 1959, after washing just 70 cubic metres of soil they made their fortune by selling out to a subsidiary of the large mining company RTZ (Rio Tinto Zimbabwe) that was then owned jointly by RTZ (53%) and the Zimbabwean public (47%)[v]

In May 1993, RTZ sold the Sandawana to a newly formed company, Sandawana Mines (Pvt.) Ltd in which the Zimbabwean government was a minor shareholder.

Since the mines came under new ownership in 1993 much more consistent production was established and in addition to the small sizes for which Sandawana was known, greater numbers of polished stones as large as 1.50 carats were produced. In recent years mining at the most active area, the Zeus mine, was done underground, with the ore processed in a standard washing / screening trommel plant.

The new ownership brought renewed attention focused on exploration and mining, with excellent results in terms of both the quantity and quality of the stones produced. Additional investment provided new mining equipment, transportation, housing, and important improvements to underground mining and ore processing.

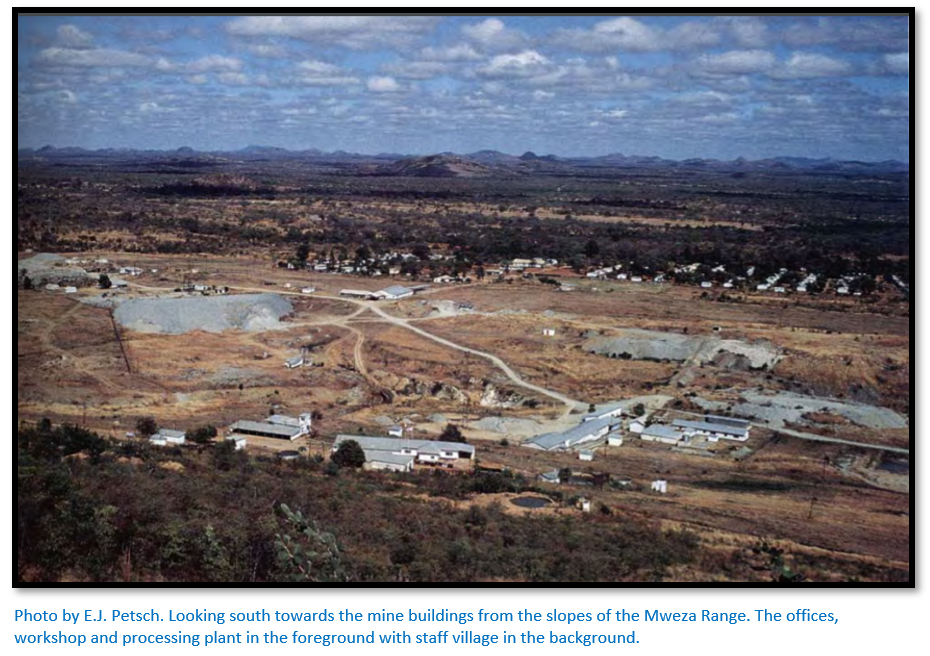

The company, which was headquartered in Harare employed about 400 workers at the mine of which 60 were security officers. As is the case with most gem mines, security is a major concern. The Sandawana mining site had its own medical clinic, essential in this remote area and a primary school. There was also a sports-clubhouse, a soccer club, a community hall, a general store, as well as regular bus service to Harare.

Sandawana went into care and maintenance in 2012 but other Zimbabwe emerald mines are currently operating.

Landela Mining Venture is owned by Zimbabwean businessman Kudakwashe Tagwirei, Chief Executive Officer of Sakunda Holdings Group, who is a ZANU-PF stalwart and closely connected with President Emmerson Mnangagwa and is already a joint venture partner in the Russian-led Darwendale platinum mine project and in discussions with Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC) to purchase four idle state-backed gold mines in the country. These mines were viable but have been bankrupted through poor past national economic and political decisions.

There have also been recent rumours that Landela Mining Venture is in discussions with the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC) to buy Sandawana.[vi] Political connections and cronyism is what it takes to do business in Zimbabwe rather than investments which are in the best interests of the country and its citizens.

What are the characteristics of Sandawana emeralds?

Sandawana emeralds are quite small, polished stones averaging about 0.08 carats, but they mostly have an attractive bluish-green colour which they retain even when cut. Sandawana emeralds typically show even colour distribution and are slightly to heavily included and are characterized by an extremely high chromium content.

Columbian stones have more of a yellow tint and become lighter when cut into small stones. Their history has been a bloody from the time the Spanish arrived to the 1980’s when the mines of Muzo found themselves in the sights of Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellin drug cartel, who thought the emeralds could be a means to launder the profits from the cocaine industry.

Was Sandawana a world producer?

No, in terms of quantity Sandawana emeralds was a small producer. Colombia, Zambia, and Brazil have produced much greater volume of emeralds compared to that of Zimbabwe. Colombian output fluctuates between 50 to 95% of world output depending on annual production with Zambia the second largest producer and Brazilian, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Russia, Nigeria, Madagascar and Canada all producing emeralds.

How desirable are Sandawana emeralds?

Although they are small, Sandawana emeralds stand out for their beauty and the quality of their colour as one of the most prestigious, beautiful and rarest gemstones in the world, so they retain value well. Their deep green colour comes from chromium.

Larger high-quality Sandawana emeralds are extremely difficult to obtain, and prices are over three times that of diamonds of the same size. As always their value is determined according to their colour, their weight (number of carats) and their clarity (number of inclusions) and to the owner of an emerald ring it doesn’t really matter where the emeralds have been mined.

How many carats are the biggest emeralds?

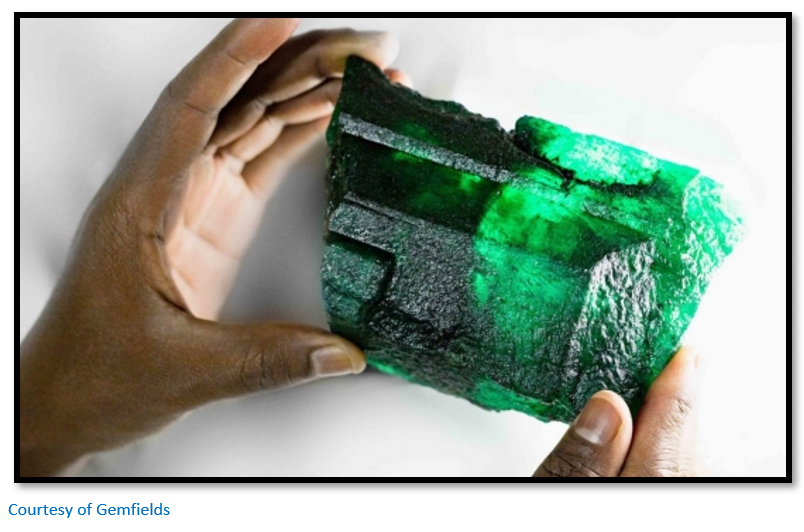

Emerald crystals can grow very large.

The world’s biggest-ever emerald weighed 1.1kg and is a 5,655 carat gemstone found by the mining company Gemfields at Kagem in Zambia in October 2018. It has been named Inkalamu which means lion in the local Bemba language and is worth an estimated £2m.[vii]

The Devonshire emerald is in a vault at the Natural History Museum in London and weighs 1,386 carats. It belongs to the Duke of Devonshire and is from Musa in Columbia.

Columbian or Sandawana emerald?

Colombian emerald tends to be the popular choice as they are more freely available and therefore, less expensive. Their colour ranges from a yellow-green which comes from vanadium to a very dark blue-green. Sandawana emeralds are always a rich blue-green from the chromium and the mine is no longer producing, so they have a rarity value that the Columbian emerald does not have.

Some spectacular Colombian emeralds have been found with very good colour and even fewer inclusions than Sandawana emeralds, but those in the know state that the colour of the Zimbabwean stones is superior and they fetch higher prices.

Are emeralds more valuable than diamonds?

Larger emeralds of three carats or more have a greater value than diamonds. Initially emeralds greater than three carats were found at Sandawana, but the supply of larger stones quite quickly ran out and for more years the average size was half a carat. One emerald specialist said: “The finest emerald I’ve ever seen was a 3-carat Sandawana stone shown me in 1980. It’s owner, an Indian dealer, wanted a mind-boggling $60,000 per carat. But eventually he got it.”

How do emeralds compare with diamonds?

They don’t! Many people consider diamond as more valuable than emerald, but this is not always the case. The quality and rarity of these gemstones are extremely important factors which determine the value of a finished diamond compared to a finished emerald. To give you a rough estimate, the price range between a 1 carat round diamond and a 1 carat round emerald can lie between:

Diamond: 1 carat = From $1,500 to $25,000

Emerald: 1 carat = From $250 to $10,000

What determines the value of an emerald?

The depth of green colour and clarity of a stone and the way the stone has been cut is also important in determining the price per carat. These characteristics ensured Sandawana emeralds were often valued at double the price of Colombian emeralds.

In addition emeralds which obtain their colour from vanadium rather than chromium are considered less desirable. There are technical differences between the American Jewellery Council (AJC) and the international standard as to the definition of emeralds. The AJC considers that when vanadium is responsible for making a beryllium stone green, then it is considered an emerald. The international standard, however, believes a beryllium stone can only be considered an emerald when it is coloured green by chromium, as in Sandawana emeralds. So technically, Columbian emeralds aren’t considered to be emeralds at all outside of America!

Emerald rings range in price from about $300 for a vanadium emerald (Colombian) under one carat to thousands of dollars for a three carat chromium emerald (Sandawana)

Emerald or Diamond?

Almost all emeralds have inclusions which make emeralds much softer and weaker than diamonds so they break easily and need to be worn with care. In technical language they have a MOHS hardness of between 7.5 and 8.[viii] Emeralds without inclusions are quite rare and to the many stones with inclusions oil is added by jewellers to make the inclusion less obvious to the naked eye. Any inclusions within a stone will to some extent weaken it, but the length of the inclusions will have an obvious bearing. Prized diamonds have no inclusions or discolouration…the most prized are blue-white.

Are emeralds commonly oiled?

Yes, they are! Oiling is the filling of surface reaching cracks or fissures in the emerald with a natural oil such as cedarwood because it is colourless and has a refractive index close to emerald. The oil improves an emerald’s appearance by decreasing the visibility of fractures and improving the transparency of the stone. However the oil does dry out and emeralds have to be re-oiled from time to time to keep them looking their best.

Emerald cutting

Emerald’s relative hardness protects it to a large extent from scratches, but its brittleness and its many fissures (the inclusions) can make cutting and cleaning rather difficult. Even for a skilled gem cutter cutting emeralds presents a special challenge, firstly because of the high value of the raw crystals and secondly because of the frequent inclusions or mineral deposits within the stone. So much so, there has been a special cut primarily developed with emerald’s in mind: The Emerald Cut. The clear design of this rectangular or square cut with its bevelled corners brings out the beauty of this valuable gemstone to the fullest and at the same time protects it from mechanical strain.

Jaipur, India is the cutting centre for most emeralds these days. The emeralds shown below are all from Sandawana and have been oiled but not heat-treated and for sale on the wildfishgems.com website. Their website states all Sandawana emeralds over one carat are considered a rarity. At the time of writing in 2020 their inventory of Sandawana stones was the largest in the trade: “but no new material is coming onto the market, the mines have been emptied long ago, their consistent quality is legend, perhaps the best emeralds found in history.”

Examples of Sandawana eneralds

What about synthetic emeralds?

Synthetic emerald stones start from about $15.00 per carat. It is impossible to differentiate between a natural emerald and a synthetic emerald with the naked eye as both are produced using the same natural minerals (i.e. the chemical and gemmological composition of synthetic stones is identical to mined stones) Ultraviolet light is used to assess whether emeralds are man-made or mined.

Are Sandawana emeralds still being mined?

The Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC) website states the mine changed hands over the years and currently ZMDC has a majority shareholding at Sandawana Mines. The mine consists of a number of emerald claims including Ceres, Athene, Eros, Marmaid, Junc, Zeus, Atom, Plato, Vulcan among others.

Sandawana has been an important producer of emeralds for 56 years and mining appears to have ceased about 2012 with the site existing now only on a care and maintenance basis. Whether this was through poor economic and political factors or because deposits became exhausted is unclear.

In 2012 www.emeraldmine.com reported Sandawana mine’s closure which was confirmed by the chairman of Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC) Godwills Masimirembwa. When Radio VOP visited the once thriving emerald mine it now resembled a ghost town with all main gates locked up and only 15 security guards manning the mining site. “Since the government took over this mine [in 2006] all has not been well, many people lost their jobs and were evicted from mining company houses. As you can see, there is no more Sandawana Mine to talk about. It is now a ghost town because of poor management and looting by the previous government” said a headman from a village adjacent to Sandawana Mine.

History of emeralds

The Muzo are an indigenous people who lived in the Colombian Andes and are sometimes referred to as the ‘Emerald people’ because they were known to mine the gemstone 1,500 BP. They resisted heavily against the Spanish invaders but were eventually overcome and it wasn’t until 1564 that the Spanish Captain Juan de Penagos was brought to the source of the mysterious green treasures of Muzo. Don’t believe any tales about the Spanish stumbling upon Muzo, it is simply too remote for that. Once they controlled the output the Spanish conquistadors brought back and introduced emeralds to Europe where they became much prized and until modern times Muzo has been the world capital for these precious green gemstones.

The rough emeralds above were found on the wreck of the Nuestra Señora de Atocha a galleon bound for Spain in 1622 which was heavily laden with copper, silver, gold, tobacco, gems, jewels and indigo. The ship had sailed from the Spanish ports at Cartagena in Colombia and then Panama and sank off the Florida Keys in a fierce storm.

In 2014, the Atocha was added to the Guinness Book of World Records for being the most valuable shipwreck to be recovered, as it was carrying roughly 40 tonnes of gold and silver and 70 pounds (32 kg) of rough Colombian emeralds.[ix]

For centuries emeralds were considered the most desirable of gemstones and eagerly sought after by royalty, the aristocracy and the very rich as they signalled to anybody who saw them the high status and wealth of those wearing them.

In the early 1940’s Sir Ernest Oppenheimer created an artificial scarcity of diamonds by creating the De Beers diamond monopoly and controlling the supply of diamonds by only releasing a limited number and through pricing. He also used an American advertising company to create the extremely effective campaign featuring “A diamond is forever.” This case study is often used in marketing courses and was arguably the most successful advertising campaign in history convincing many women that a man’s love can only be demonstrated through a valuable diamond ring.

The geology of the Sandawana area

The Mweza Range is composed of very old pre-Cambrian rocks extending for some 70 kms (45 miles) east-north-east in a large area of granitic rocks that are also of pre-Cambrian age. The range is 3 – 5 kms wide (2 – 3 miles) and rises about 150 – 200 metres (500 - 800 foot) above the surrounding country.

The core of the Mweza range is a variety of banded sedimentary rocks that have been metamorphosed and now contain micas, almandine garnet and various amphiboles, including grunerite consisting of banded ironstones, phyllites, sericite-quartz schists and quartzites. Very long, narrow sills of peridotites were intruded into these older rocks and have been altered into serpentine and related rocks.

The range was folded, metamorphosed and intruded by granitic rocks at the end of the Bulawayan times and again at the end of Shamvian times about 2,650 million years ago. A batholitic mass of granitic rocks extends for over 30 kms (20 miles) in all directions from the range and in parts has intruded into the schists of the range and the gneissic granite contact around it.

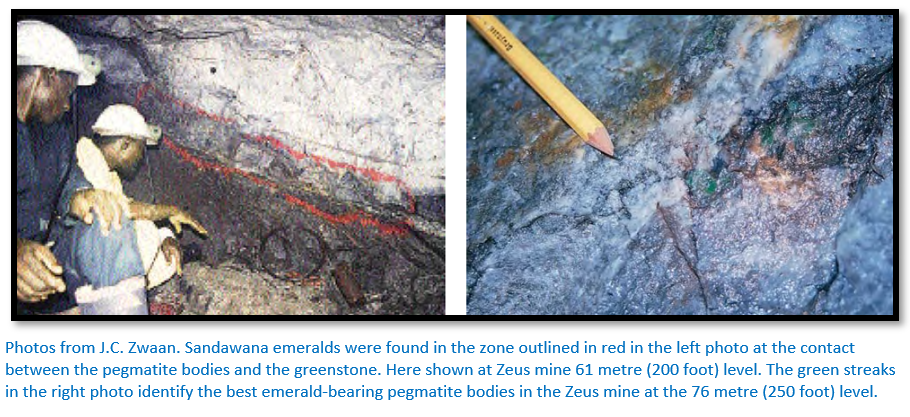

The emeralds have been found associated with the pegmatite dykes in the tremolite schists. The majority of the pegmatite dykes probably belong to the end of the Shamvian System and contain beryl, lepidolite, petalite, spodumene and tantalum-niobium minerals. The intrusion of the granitic magma into the tremolite schists caused contact-metamorphosis of the two rocks through which new minerals were formed, the most valuable of which is emerald.

Beryllium is an element that comes from the granite as the tremolite schists do not carry any beryllium. Chromium which acts as a pigment is present in minute quantities in the altered serpentine rocks and in the course of the numerous successive intrusions, alterations and re-formations became an ingredient in the process of contact-metamorphosis, thus becoming responsible for the superb colour of the Sandawana emeralds.

E.J. Gübelin the author of the above paragraphs was given a lot of 92 Sandawana stones to find out their local peculiarities and other typical characteristics and to establish how they differed from other known emeralds. He writes that they all displayed a superb verdant emerald green with a brightening yellow glint that made the stones very vivid. To the naked eye the gems appeared amazingly clean and only in a few of the specimens a denser concentrations of inclusions altered the colour into a more bluish-green hue.

Most of the rough material showed as small crystals only and he estimated that most of the Sandawana cut emeralds reaching the market of cut gems would be below 1/4 carat in weight although he thought larger gems might appear as the deposit was exploited. The largest Sandawana emerald obtained to that date weighed 1·56 carat as a cut gem but the good news was that even small carat sizes kept the unrivalled beauty of colour which seemed to be the outstanding virtue of the Sandawana emeralds.

World trade in emeralds

Much of the world’s rough (i.e. uncut) emeralds are traded illegally on what is euphemistically called

“the grey market.” Daniel Howden’s article describes how in the remote reaches of Colombia thousands of poor and desperate gem prospectors risk this wild frontier of gangster rule, left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries and the army in the hope of striking it rich.

The bulk of the world’s emeralds come out of a tiny valley, an exhausting hike out of the town of Muzo, itself in the middle of nowhere. Some sort through the gravels of the Rio Minerva as “guaquero’s” hoping to spot green, others descend the dozens of ramshackle mine shafts searching for the green gems and the fortune they all hope for.

When Howden spoke to the man in charge of one of the mines he was told the first rule of mining is to accept that you might not be coming back up. "When you understand that you're less likely to panic once something goes wrong down there." A battered cage at the mine lowers …nearly 200 metres into the darkness in what feels like a pitch-black waterfall. As the cage descends the temperature rises rapidly and water rains down continuously soaking everything. The bottom of the shaft is hotter than a sauna and claustrophobic. The miners walk over narrow planks and up crude ladders until the deafening roar of jackhammers signals the working face has been reached.

When emeralds are found at depth in these mines they must be dug carefully out of the black carbon surface to reveal the raw emeralds that stud the rock’s surface; impossibly green and shining in the lamplight. Because of their value, there is a large illicit market operating in emeralds and they remain the preserve of prospectors, gangsters and dealers.

Along Bogotá's Avenida Jimenez is the centre of the illicit emerald trade where the rough gemstones are bought and sold; emeralds are bought and sold typically six times between the mines where they are sourced to the streets in downtown Bogotá. The stones wrapped in white paper are carefully inspected using tweezers to hold the gemstones to the light as potential buyers search for imperfections in the form of inclusions and look for the green shade they are seeking. Sellers and dealers will bargain and finally secure a deal.

Because of this illegal trade there are no figures for total emerald rough production, but estimates put annual worldwide production at about $200 million.

The illegal trade in emeralds

Colombia’s lightly regulated emerald trade has long been a sector that straddles the line between the legal and illegal worlds. Regulated sales represent just a fraction of the profits on offer; with illegal sales and opportunities for laundering drug profits the real attraction for many.

For decades, the unchecked trade has attracted murky characters, from emerald magnate Pedro Rincon, alias "Pedro Orejas" to Victor Carranza who was suspected of operating his own private army and having ties to paramilitary groups, to drug traffickers such as Pablo Escobar and his associate Jose Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, alias “El Mexicano.”

The explosive mix of powerful criminals and vast profits led to frequent bloodletting, which erupted in the 1980’s in a series of “Green Wars” which claimed over three thousands lives.

Is green beryl classified as emerald?

No, green beryl is often found in the same mines as emeralds but are a much lighter green and it is the intensity of the colour which differentiates green beryl from emerald. Clearly this will be reflected in the price which is much lower in green beryl.

The Sandawana mine site

Exploration

The mining lease and claim holdings cover a 21-km-long strip along the southern slope of the Mweza Range. They are bordered on the north by the densely populated Mberengwa Communal Lands. On their southern flank, the Sandawana claims share a 16 km-long electrified game fence with “The Bubiana Conservancy.” This syndicate of seven different ranches, which covers an area of 350,000 acres represents one of the largest private game reserves in the world and is supported by the World Wildlife Fund.

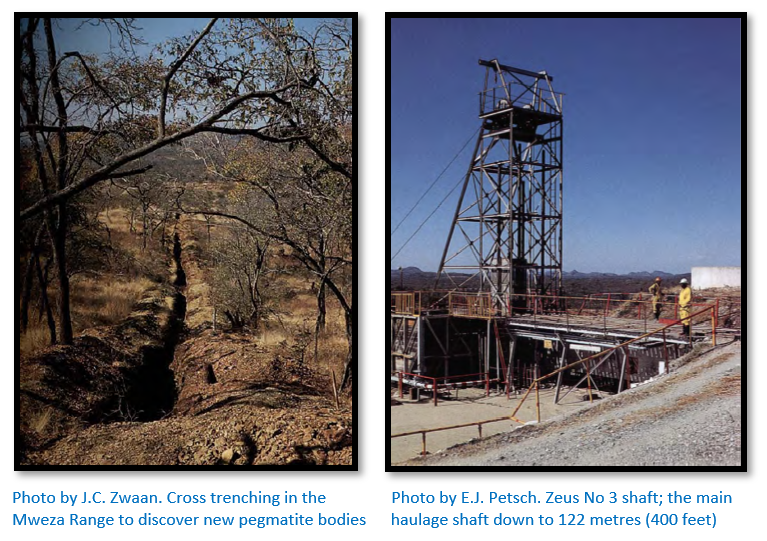

Since the discovery of the Sandawana deposits in 1956, an almost continuous exploration program has been carried out within the 21-km-long claim holding. Over the years, systematic trenching and surface drilling of profiles for structural studies has led to the discovery of other emerald-bearing sites including Eros, Juno, Aeres and Orpheus.

After extensive trenching, surface drilling, sampling, and some open pit mining, exploration shafts were sunk at the Aeres and Orpheus sections. These prospects are 3 km north-east and 10 km south-west of the Zeus mine, respectively.

Mining

Since the earliest days emerald exploitation has been concentrated mainly in the Zeus area. The Zeus mine was an open-cast operation initially until the pit reached 15 metres deep. Petsch states it was so rich in emeralds that the location was nicknamed the “Bank of England.” Subsequently the Zeus mine was developed into a modern underground mine. Over a strike of 700 metres four vertical shafts have been sunk. The No. 3 shaft served as the main production shaft reaching levels as far down as 122 metres (400 feet) Below another almost vertical shaft serves the mine from 122 metres (400 feet) to the 152 metre (500 feet) level. Levels and sublevels are 7.6 metres (25 feet) apart vertically and are connected by raises.

Drifts (horizontal tunnels) are mined along the hanging and footwall contacts of the pegmatites and mining of the emerald-bearing shoots is done by stoping methods. Ore is removed from the stopes via small tunnels called ore passes. It is then transported in cocopans (ore carts) on rails to the haulage shaft. More than 40 kms (25 miles) of tunnels and shafts have been dug at the Zeus mine.

All underground survey data was plotted on a composite mine plan, scale 1:1000 and since its inception the survey department has maintained a three-dimensional model of the underground mine workings.

Processing

After dynamite blasting any rock with “green” in it is taken from the ore-zone in the stopes and transported to the processing plant and batch processed. Any exceptionally rich matrix with fine-quality emeralds visible is hand-cobbed underground and treated separately from the normal run-of-mine materials. Some of these pieces are selected for sale as collectors’ specimens. Waste rock is dumped near the haulage shaft and taken up as less of a priority.

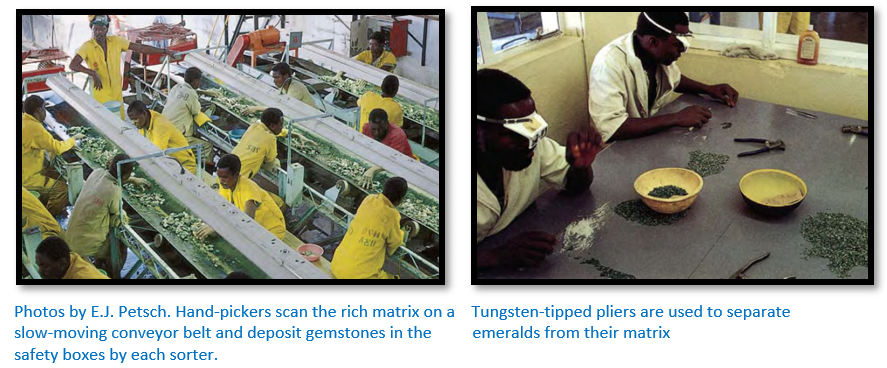

The processing plant was a standard washing/ screening trommel plant with a capacity of approximately 300 tons of ore per month. About 42 people worked there, eight hours a day, five days a week. After the ore passes through a 24 cm grizzly-grid it is broken by a jaw crusher. (Although some emeralds might be slightly damaged by the jaw crusher, there is no alternative for large tonnages) The ore is then washed and sized, with the largest (over 20 mm) and smallest (under 3 mm) pieces separated out in a rotating trommel. Additional vibrating screens further separate the material into specific size ranges, so that larger and smaller pieces were not mixed for the next stage of sorting on slow-moving conveyor belts. Under strict security, 30 hand-pickers scan this material for emeralds.

For emerald recovery from the 1.6 – 6 mm material Sandawana introduced innovative processing technology based on gravity separation. The DMS (dense media separation) module with a capacity of one ton of ore per hour, was originally designed for diamond processing. This technology enables the mine to recover those smaller emeralds that might be overlooked in the course of hand sorting.

At the next stage “cobber’s” use tungsten-tipped pliers and chipping hammers to liberate the emeralds from their matrix with a minimum of damage.

Lastly all the rough emeralds were sorted according to size, colour, and clarity to prepare parcels for the international market. The entire processing plant area is surrounded by a security fence, patrolled by security staff and monitored by security officers using closed-circuit television.

Sandawana rough

The majority of the rough emeralds are recovered as crystal fragments and break easily when they are removed from the host rock or processed. Most of the emeralds are medium to dark green. Sandawana emerald crystals are typically small and most gem-quality material is between 2 and 8 mm, although opaque crystals as large as 12 mm are seen. The Zeus mine regularly extracted larger crystals of 25 - 100 carats each but precise numbers are not published.

Since 1993 when the mine was sold by Rio Tinto Zimbabwe to Gemstone Resources Limited monthly emerald production improved considerably and became more consistent. Most Sandawana polished stones weigh between 0.25 and 0.80 carat, but stones weighing above 1 – 2 carat were sometimes produced. Cut Sandawana emeralds of 1.50 carat or more are rare.

The quantity of emeralds produced varied from month to month, but for the 1993 – 1996 period published figures showed a production of at least 60 kg of mixed grades of rough emeralds per month of which 10% is usually transparent enough and of a sufficiently attractive colour to be faceted or cut as cabochons.

The largest crystal that one of the authors (JCZ) has seen was 1,021.5 carats found at the Orpheus mine in 1995. Some of the larger crystals from Orpheus were found in khaki-coloured altered schist near a pegmatite at the surface. Most of these large crystals contain a substantial portion that is suitable for cutting. The average retention after cutting is 10–20% of the original weight.

Production and Distribution

From 1965 after Rio Tinto had owned Sandawana for seven years it decided to switch to a distribution system based on the De Beers single-channel market model for diamonds putting sales of rough and cut stones in the hands of French gem dealer Jean Rosenthal. He assigned five dealers, himself included, exclusive franchises in France, Germany, Switzerland and the Americas.

For New York dealer Maurice Shire, who oversaw sales in the U.S. from 1965 until 1983, it was a business arrangement as close to ideal as the product itself. Once every 10 to 12 weeks for over 18 years Shire flew to Paris where he bought the equivalent of a ‘sight” in Sandawana gems, the most desirable small emeralds in history. While these offerings cost him on average $300,000 to $400,000; he says: “they were worth every penny.”[x]

At least for the first 10 years. Then the assortments tapered off in terms of quality and quantity without a corresponding drop in price. In 1982, the Zimbabwe government insisted buyers come to Africa. By then, prices for Sandawana stones were $1,600 versus $700 per carat for Zambian emeralds and Shire gave up his U.S. concession in 1983.

Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe (MMCZ)

Sales of all gem materials (rough and cut) in Zimbabwe are monitored by the Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe which was established through an Act of Parliament (MMCZ Act Chapter 21:04) and began operations in March 1983. It is 100% owned by the Government of Zimbabwe and falls under the ambit of the Ministry of Mines and Mining Development. It is an exclusive agent for marketing and selling of all minerals produced in Zimbabwe except silver and gold.

As regulated by the government, part of the production is cut locally for export from Zimbabwe. However, the greater part of the rough material is sold to traditional clients and in recent years also at regular invitation-only auctions. However there have been allegations this organisation has been corrupted and valuable gems are siphoned off for the benefit of political cronies. The Sunday Mail of 10 July 2016 published an article stating MMCZ was being investigated for nepotism, fraud, extravagant allowances and collusion with foreign diamond buyers to manipulate the price of local gemstones including rough emeralds and diamonds and that senior management were helping themselves to housing and vehicle loans, school fees, travel and accommodation allowances.

In a familiar story there are allegations that there is collusion between MMCZ gemstone evaluators and gem buyers, especially from India. Precious stones are under-invoiced in return for “kickbacks” from dishonest and dodgy buyers.

The future for Emeralds in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe has been home to over 800 mines in the past. Most have been shut down or placed under care and maintenance in the past two decades because the once-thriving mining industry has been destroyed for a number of reasons. They include unfavourable local economic conditions such as inflation, hostile indigenization laws requiring foreign owners to relinquish 51% of the shares (now rescinded, but the damage has been done) steep corporation tax and high import duties which have increased as the economic base has withered away, high operational costs from an increasing government imposed bureaucratic burden and bureaucratic corruption in state organizations such as MMCZ and in some cases unfavourable prices of minerals.[xi]

Zimbabwean citizens are prevented from accumulating any amounts of foreign currency, as well as transferring significant sums of money out of the country. One of the results is that gem smuggling of emeralds has long run rampant. This has been exacerbated by ZANU-PF “high-ups” leaning on mining operators and threatening to get mining licences withdrawn unless precious stones are diverted from official channels into their own pockets.

Corruption and theft are now endemic in ZANU-PF; Zimbabwe has become much like the “wild frontier” of Muzo in Colombia although the disease may not be so evident to the passer-by, but it is there. State Enterprises described above are part of the problem…competence and integrity have been replaced by party loyalty and cronyism, that is the appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications has become the order of the day. Lieutenant-Colonels retired from the army are rewarded with the top positions because of their loyalty and once-thriving mines such as Sandawana have been run into the ground because the funds that should be invested in new plant are used to buy the “big cheeses” Range Rovers and other luxuries and the stolen monies from gemstones are invested in villas in Dubai.

References

Böhmke F.C. (1982) Emeralds at Sandawana. In Gemstones, Report of the Sixth Annual Commodity Meeting, Institution of Mining and Metallurgy (IMM), London.

E. J. Gübelin. Emeralds from Zimbabwe. The Journal of Gemmology, Vol. VI, No. 8, October 1958

D. Howden. Fighting Colombia's Green War: Treasure of the emerald forest. The Independent Newspaper, 29 April 2006

J. Kanis, C.E.S. Arps, P.C. Zwaan. 'Machingwe': A new emerald deposit in Zimbabwe. The Journal of Gemmology, Volume 22, No 5, January 1991

T. Schlesinger. The Story of Sandawana and Columbian Emeralds

T. Schlesinger. The Most Famous Emeralds in History

J. C. Zwaan, J. Kanis and E.J. Petsch. Update on Emeralds from the Sandawana Mines, Zimbabwe. Gems and Gemmology. 1997

Sandawana Emeralds - Better Than Colombian Emeralds? https://hubpages.com/style/The-Sandawana-Emerald-Best-Engagement-Ring

https://www.insightcrime.org/news/brief/grenade-attack-in-colombia-raises-specter-of-new-emerald-war/article by J. Bargent on 14.11.2013

[i] Emeralds from Zimbabwe article

[ii] Pegmatites -

[iii] Update of emeralds article, P82

[iv] Machingwe, P264

[v] Ibid

[vi] Bulawayo Chronicle 23/07/2020

[vii] https://inews.co.uk/news/worlds-biggest-emerald-inkalamu-2-million-zambian-mine-216336 article by Josh Barrie

[ix] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/16/rare-emeralds-found-400-year-old-shipwreck-expected-fetch-millions/ article by Helena Horton

[xi] Mining.Zimbabwe.com. Ten mines that Zimbabwe should urgently revive article by Justice Zhou on 14.12.2018