Home >

Matabeleland South >

The Kirby family and their Salvation Army connection in early Rhodesia with the Usher Institute from 1946 and the Tshelanyemba Institute in the Semokwe Reserve from 1948 – 1954 followed by international assignments in Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia

The Kirby family and their Salvation Army connection in early Rhodesia with the Usher Institute from 1946 and the Tshelanyemba Institute in the Semokwe Reserve from 1948 – 1954 followed by international assignments in Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia

Part 1 of 2 is under Mashonaland Central.

Leonard Andrew Kirby, the father of the author of this article is referred to as “Dad,” Leonard Field Kirby, the author is “I, or the author.” Rose Emma Field is “Mum” and “Rose” is their daughter and “Andrew” is the youngest son.

Usher Institute, Figtree and furlough in Canada

All my service as an officer had been at Howard teaching industrial and handwork and I wrote to the Teacher Training School in Ontario asking if I could join a course and was told the next course began 10 September 1946. Sir Godfrey Huggins, the Prime Minister, supported my application and the course fees were waived. Captain Jack Horwood replaced me at Howard and I was sent to Usher Institute at Figtree, Matabeleland, as acting principal whilst Major Clements was on furlough.

In May 1946[i] we left Usher for Canada where I did my course, met all of Isabel’s family, and we left in January 1947

Usher Institute and the April 1947 royal visit

Back in Southern Rhodesia our new posting to Usher Institute was not new to me as my parents had been principals for some years. It was a boys and girls boarding school in Matabeleland on a farm of about 4,000 acres near the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) border. We had a good herd of goats, sheep and cattle, but wild dogs (painted wolves) were a menace and one night I had to shoot one to keep them away. We always kept some goats with the sheep as they were better at finding their way back to their kraal!

Captain Myrtle Pitcher married Captain Ed Deering whilst we were there; unfortunately the grass roof of the kitchen / dining room caught fire as lunch was about to be served, nobody was hurt, but the food was ruined. They left for their next posting at Mbembeswana, also in southern Matabeleland.

Soon after was the royal tour of Southern Rhodesia by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, along with the two princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret.[ii] Usher was only three miles north of Leighwoods siding, between Marula and Figtree on the railway line. The whole school wanted to see the royal train and three hundred boys and girls with their teachers walked to the siding and lined up parallel to the track. The train drew up and slowed to walking pace and the King and Queen stood at the rail of the royal coach and waved to everyone from beginning to end, as did the princesses.[iii]

One morning one of the best teachers, Isiah Togwe, was at the door looking shaken. He said he must leave or he would die, as he had been bewitched and wanted to be released immediately. I told him to stay at his house and we would talk about it later which we did and he still believed he must leave. He told me his father was a powerful traditional healer (n’anga) and someone was using witchcraft to make him leave.

I asked Isaiah if witchcraft was sent by God or was it from the devil. He replied without hesitation that it was the work of the devil, but that the devil was very powerful and could not be ignored. I then asked him who was the most powerful, God or the devil. He was quiet for quite a long time then he replied that he believed God was more powerful than the devil, so then I said, if God is the most powerful, will you not trust Him to protect you from what you know is a very powerful evil force which could destroy you. So we prayed together and the following week Isiah stood in front of the school and told them his experience and that he had proved that God is all powerful, and none of them need to be afraid of witchcraft, or evil spirits, because God is greater than all of them and would always protect them.

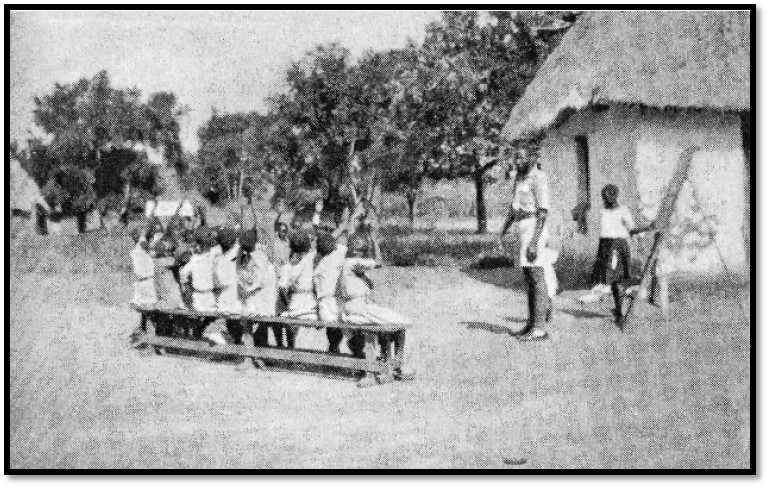

NAZ: open-air lesson at a village school

Mbembeswana and Tshelanyemba

In late 1947 we transferred to Mbembeswana, as Mrs Deering’s health had suffered. From Bulawayo the road goes through the Matobo to Kezi on gravel and then by just a track for the next twenty miles. The founding officer, Major Wackernagel wrote, "The Clinic as well as the little quarters, each had a large water tank of galvanized iron with a tap and padlock. In periods of drought when only a small supply of water was left and carefully hoarded for further emergencies, we managed to get extra water from the pump of a Government cistern which was brought by an African comrade in a petrol drum on an ox cart. Later when we had a water cart given to us, and two donkeys purchased locally, these did the job. However, if the pump was damaged through mishandling, or by small boys throwing pebbles into the tube of the pump, repairs were often not forthcoming for some time. In these circumstances, on moonlit nights at about 2 am the donkeys were in spanned and driven down into a sandy river bed where a deep hole was dug in the sand in which eventually water gathered and was collected. This was repeated until there was enough to fill the drum after which the cart was pulled and pushed up the steep bank. We could never allow a drop of water to be wasted. The water concern was far from being the only one to be faced, our problems were legion, but despite them there remains in the heart gratitude to God for His help in the never-ending difficulties."

It was not the best location because of the lack of water and it was on the very edge of our district. There were sixteen Corps and schools, some over sixty miles away. The nearest post office was at Antelope mine, thirteen miles across country by bicycle, twenty-five miles by bush track. Captain and Mrs Nhari were in charge of the Corps and School at Mbembeswana. They were a well-educated couple with seven boys, but no girls, and became Elizabeth’s only playmates and she very quickly learned to speak Ndebele as she spent most of her time at the Nhari's house.

I wanted to choose a better site in the centre of the area and spoke to Chief Malaba who said that I could have 100 acres of land anywhere in his area provided I chose on his side of the Shashani River as during the rainy season nobody could cross the flooded river to go to the Government Hospital. I looked around his area and decided on suitable site about 2 miles from Tshelanyemba village where we had a large Corps and school.

Google Earth image of Tshelanyemba Hospital, Shashani river and former sites of Sun Yet Sen and Legion gold mine in southern Matabeland

The Sun Yet Sen gold mine

This gold mine, now closed, was on the opposite side of the Shashani river and connected to Bulawayo by a gravel road. The mine had an Electric Supply Commission's main power line and good water from a well near the river and a telephone line to the Antelope mine and then on to Bulawayo. There was also a Postal Agency and General Store five miles to the south at the Legion mine. So there were good advantages to the site, but no bridge over the river itself.

Chief Malaba was very pleased and local people at Tshelanyemba were delighted and promised to make Kimberley bricks on the site. The Mbembeswana community were not very happy but reassured that the African nurse would stay and we promised to return once a week to check on the clinic’s supplies and visit the school; Captain and Mrs Nhari remained.

We move to Tshelanyemba in 1948

Initially, the three of us lived in our half ton van. The people made bricks and when dry we built a single room approximately 10 feet square with a flat galvanized corrugated-iron roof as our home for the next few months.

The Shashani river was about 250 feet wide and usually just a dry sandy river bed. To cross the river we broke down its banks and cut loads of thin poles a couple of feet longer than the width of the van and joined together with wire and stretched across the river on top of the sand, and that enabled us to drive over to the other bank, and then drive to the Sun Yet Sen mine, or Legion mine store, and the 6 or 7 Corps on the opposite side of the river. The mat remained on the sand until the rains came, when we rolled it up and kept it ready for the next dry period. When the river flooded, we could, in an absolute emergency, travel on some bush tracks about forty miles to Antelope mine where there was a causeway across the Shashani.

When never knew what the day would bring and had to be prepared for anything. At a wedding at Mbembeswana Isabel was called by the young nurse at the clinic because a patient had just arrived in a critical condition and was not expected to live very long. Native medicines and rituals had been tried for days without success, so now the family turned to the `Army' and the young African nurse was at her wits end. Isabel stayed with the nurse until there was improvement in her health and the woman returned to her village with the knowledge that the Christian's God still performed miracles through his very ordinary servants who served the community in his name.

In 1946 at Howard I continued with my B.A. in African Studies and passed Shona 2 and Native Administration 1 and in December 1948 I passed in Shona 3 but failed in the Native Administration 2. But with the increased demands of establishing the mission centre at Tshelanyemba and the growing work, I had to make the decision to give up studying. I had 16 Corps and Schools with 52 teachers to look after, with regular school inspections four times a year at each school to meet the requirements of the native education department.

Every morning patients would be waiting for Isabel for treatment as the nearest clinic was thirty miles away at Antelope mine and there was no public transport in the whole of the Semokwe in those days. None of the patients spoke English and Isabel could not understand their Ndebele, I had a limited knowledge of Zulu, and our expert translator was our daughter Elizabeth, not yet 5 years old. Often there were more than twenty people waiting for treatment and some were too sick to be treated as outpatients. The local community agreed to make more Kimberley bricks for a four-roomed building where we could have a dispensary, an outpatient treatment room, and two beds in each of the other two rooms for patients who were too ill to be out-patients.

Daughter Elizabeth with a best friend

There were men coming over from Sun Yet Sen mine for injections to clear up a venereal infection and Isabel decided that I would learn how to give injections on these patients under her supervision. Interestingly later some of the men who came over for injections demanded that they be given them by the doctor, and not a mere nurse! It took a little while to convince them that there was no doctor at Tshelanyemba! Then we employed an African nurse to work under Isabel's direction as there was far too much work for her alone and as patients increased, a second building of the same size had to be hurriedly built.

Then I built a house with four rooms with a corrugated iron roof, dhaka floors, and no ceilings, that became our home and office for the next two years, Ruth Hacking came and lived in the single room which we had vacated. We were very happy at Tshelanyemba establishing a centre which in years to come would greatly benefit the local community. People walked as far as sixty miles through the bush taking three or four days on the journey and we erected a few shelters where relatives of the sick could stay. Major Hacking did valiant service and became well known throughout the area with patients coming even from Bechuanaland.

There was no running water at Tshelanyemba when we were there and it was brought up from the river in drums on a Scotch cart. Although the river was just dry sand from one bank to the other, there was always water a few feet down to be reached by digging. We bathed in a galvanised tub after boiling some water on the wood stove.

After Elizabeth complained of a bite, the local Africans said it was a black scorpion and that she would lose her voice and become partly paralyzed for some time and might die. We took her by van to the doctor at Kezi forty miles away who said there was nothing to worry about and gave her aspirin for pain. Her throat became completely paralyzed and she could not speak or swallow anything for about five days before gradually getting better. We learned that the Kezi doctor had a patient brought in with a scorpion bite who had died, so he made enquiries and discovered that the black scorpion was the most poisonous known, and that there was no antidote for the bite.

We contacted the South African Institute for Medical Research who told us that they could make an antidote if we sent them scorpion tails and offered to pay us two pence per tail. Local people killed any black scorpions they saw, and we sent the tails off in match boxes; the money went into the hospital building fund.

On 31 March 1949 our second daughter Dorothy was born. Elizabeth's puppy took it upon himself to be her guard when Dorothy was put outside in the pram and any stranger coming near that pram really had to look out.

We build a new home at Tshelanyemba

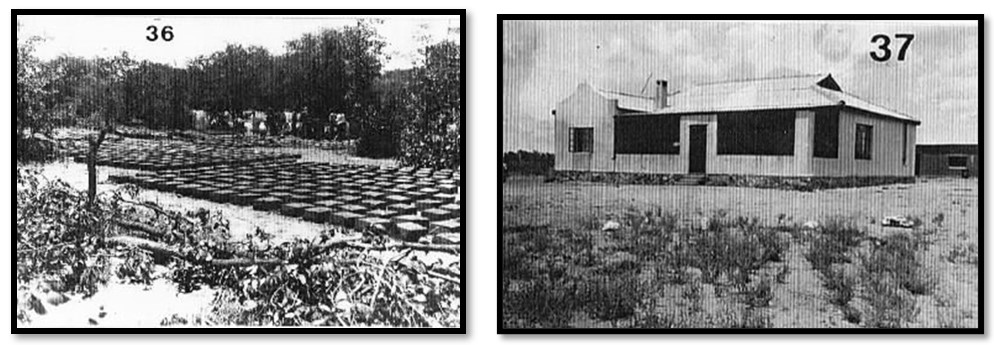

Semokwe was district given six hundred pounds for a new home and I drew up plans for a three-bedroom house using burnt bricks with a large lounge and screened-in front veranda, ceilings, and an asbestos roof to keep the house cool. With a couple of labourers we made 30,000 bricks by the river in a kiln using wood from the forest. I acquired a couple of car wheels and an axle and built a trailer to carry the finished bricks and we used rocks for the foundations. There was no money for a bricklayer, so I did all the building myself and laid conduit into the walls for the day we had electricity. The plumbing was connected to a small tank outside which we filled from drums. It was amazing how little water we used; our toilet was always flushed with water previously used for washing or bathing.

Kimberley bricks drying in the sun at Tshelanyemba The house we built with an asbestos roof – much cooler!

I had put in a request for a telephone line and the Post Office connected us with the line from Sun Yet Sen mine even before the house was ready. As it was a three-bedroom house, Major Hacking left her small Kimberley brick room and lived with us. When I visited Tshelanyemba in 1993, this house was still the Divisional Commander's house and in sound condition.

On Sunday mornings we held a service for the patients and their relatives at the clinic with usually a good attendance. This was conducted by Major Hacking, or one of her staff, or us. One year the cadets from the Howard Training College came for their ten day campaign. We had saved the life of one of the wives of the local n’anga and the cadets held a rousing open-air meeting in his village that was well attended.

Tshelanyemba Hospital

When the Territorial Commander visited us to see our clinic, he found only eight beds with over thirty in-patients occupying every bit of space, some on the lying on the floor on mats, additionally the nurses were seeing up to a hundred out-patients each day.

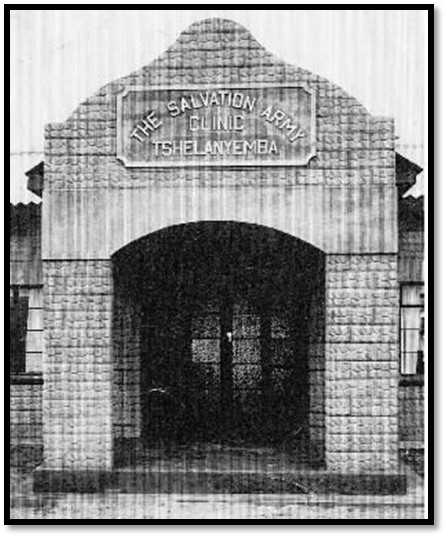

I drew up plans for a thirty-five bed hospital, with a maternity ward, delivery room, men's ward, women's ward, children's ward, out-patients room, office, store room, and male and female toilets that were submitted to the Property Board and the Medical Director and then International Headquarters in London for approval and for funds. However we learnt that all the money available for medical work for the next 10 years had already been allocated and they suggested we could re-apply in a few years’ time.

It was some months later that I was conducting a Sunday evening service for the miners at the Sun Yet Sen mine and giving a lesson on the miracle of the loaves and fishes and through my mind flashed the thought, ‘Do not just continue to pray for money to build the hospital. See what you have yourselves first, then God will take your little loaves and fishes and multiply them.’ I was prepared to do all the building myself and Isabel agreed to run the division. An understanding school inspector at the Ministry of African Education agreed to register Isabel as responsible for half of the schools so she could do the school inspections. This meant that we could go out early in the morning, I would drop her off at a school where she would do the inspection, and I would drive to the next one, do that inspection then pick up Isabel, and head for home.

We needed to raise funds and after seeing a Bulawayo newspaper advert reading. 'Old bones needed, will pay three pounds per ton' we borrowed a five ton truck from our good neighbour, Ed Delaney who owned the Legion mine store, free of charge and took the bones to the factory near Bulawayo. The bones weighed five tons, so I expected to receive my first fifteen pounds toward the hospital, but they were now offering nine pounds and gave me a cheque for forty-five pounds. With this we bought cement and next morning employed two workmen to start digging the foundations for one of the hospital wards and filling them with rocks.

Donations then started arriving from around the world and so we laid the foundation for the complete block. Then when the foundations were complete, we started making cement blocks with a rock face design for a pleasing outside appearance. They were made by two men at the Shashani river from sand and cement and kept moist for the cement to dry hard over ten days. Then they were loaded into the small trailer and taken the mile to the hospital site.

The front of Tshelanyemba Clinic, the blocks with a rock face design

Ed Delaney was always ready to lend me his five ton truck at no cost to buy the cement and lime, steel window and door frames, timber for the roof and ceilings, asbestos roofing and ceiling sheets. One day I had been over to the cement factory near Gwanda for a five ton load of cement and was only five miles from Tshelanyemba when the electric fuel pump failed. I scribbled a note to Major Hacking asking for an enema set. She thought it was a strange request, especially when the messenger said we had trouble with the truck, but she did not query it. I always carried a spare can of petrol with me, so after attaching the rubber tube directly to the carburettor, I filled the enema container with petrol, and had one of my men hold it high above the engine while sitting on the mudguard and it worked like magic. The engine started and we went about two miles when I had to refill the container, but after two refuelling stops we arrived home safely, and Major Hacking's curiosity was satisfied!

Roads in the Semokwe Reserve were very rudimentary

Everything was done on a cash basis and we never ran out of funds. In time assisted by the two village men, we put up the building, plastered and painted the walls, cemented the floors, put in the ceilings, hung the doors, fitted the asbestos roof and ceilings to keep it cool inside. However I knew it could not be used without equipment, so I wrote to the Beit Trust, but they replied saying they were unable to help with equipment, but they could pay for a power line, or water scheme. I sent the Beit Trust an estimated cost of £1,200 for a power line, digging a well on the river bank, and laying pipes to a storage tank at the hospital. Imagine my surprise, when three weeks later I opened a letter from the Trust enclosing a cheque from the full amount, and an additional £500 for buying beds, cupboards, mattresses and blankets.

On 16 December 1953, the hospital was officially opened by the Territorial Commander, Colonel Theodore Holbrook, the Children's Ward was completely furnished with money from the London Citadel Corps, a brass plaque on the door commemorates this gift and until we retired they gave between $300 and $400 every year.

Tshelanyemba 1950 - 54

Soon after the opening, Major Hacking took home furlough and Isabel took responsibility for the thirty-five bed hospital and three African nurses. However most of the babies arrived after midnight and I did not like her walking down to the hospital at night with snakes about. So I decided to teach her to drive the van and everything went well for a week or two, then I found there were no brakes. Isabel had forgotten to release the hand brake and the shoes needed replacing!

With the better hospital accommodation we received an increasing number of calls to bring in patients and in one month I travelled 450 miles over bush roads bringing in patients who could not get to the hospital in any other way. Food was not provided for them as it was always the custom for at least one relative to accompany a patient to hospital and remain with them until they returned home. We built a place for the relatives to sleep and cook.

At the time village schools only went up to Std 3 and there was a real need for a centre where the brighter students could complete their primary schooling. Tshelanyemba was the obvious choice as an electricity supply had been promised. Initially we could only provide boarding facilities for boys and the girls had to be day students, so many girls arranged to stay with local families. The classrooms were a few hundred yards from the hospital and we started in 1950. Isabel taught domestic science and mother craft. A Corps was opened for the students, patients and relatives staying with them and was named the ‘Kirby Corps’ after we left.

The Electric Supply Commission brought in the main power line from the Sun Yet Sen mine just before we left Tshelanyemba, everything in both the hospital and house had been prepared, and I had built a room for meter board and distribution switches ready for that day. We also dug a well on the Shashani river bank in the dry season and installed a pump and electric motor and laid a pipeline about half a mile to a large tank mounted on a stand near our house.

Isabel taught Elizabeth using the government correspondence course, but at eight years old we felt that she should attend a proper school. She became a boarding student at Hillside School in Bulawayo, but hated leaving home and cried when we went to visit her once a month. In the last few days of her school holidays she would become very quiet and upset, which upset us and we missed her, but it was the price we had to pay because of the work that God had called us to do.

Flag-making

We noticed when we visited the various corps that their flags were very tattered, or they did not even possess one. None of the corps had money to buy a new flag, and there were no funds to buy them, so we decided to make our own. We bought material in yellow, red, and blue at a wholesale merchant and Isabel and I got to work making full size flags for every Corps. This took most of our evenings and spare moments for some weeks but we managed and they lasted for many years in good condition.

Semokwe Corps displaying the flags we made for them

Farewell to Tshelanyemba

By then it was time for us to say good-bye to Tshelanyemba where we had spent some very happy and rewarding years and in August 1954 we left for Cape Town and England and Canada on our homeland furlough. Thus ended our service in the Semokwe with the lovely people who appreciated so much for what we tried to do for them.

Home furlough

Whilst in Canada we learned that my mother, soon after their fortieth anniversary, had died of cancer on 3 October 1954. In a Territorial Newsletter about this time the following appeared. "I had a most cheering letter from Major Kirby (R) with a cheque for two hundred and twenty five pounds as his first contribution for the erection of a quarters in memory of his warrior-wife, the first Mother of the Howard Training College. The Central Mashona Division also raised seventy five pounds toward a quarters."

The following is part of Mrs Brigadier Salmon’s tribute. "It is my sad privilege to pay a tribute to a beloved friend and comrade officer, and I feel that this I can truthfully do. Many things in life only become clear when we look back, and it is often so with people we have known. often their very nearness hides them and it is only when we look back through eyes which sorrow has cleansed, that we see them as they really were. We do not have to come to a day like this to realise the beauty and choiceness of Mrs Kirby's life and character, it has been quietly apparent right through the years, and we who have known and worked with her thank God for every remembrance of her.

We first met Mrs Rose Kirby thirty four years ago in London, we were in the same missionary group, en route for various destinations, and it has been my privilege to see her in many circumstances during the years that have intervened. I think of her as a wonderful wife and mother as she took her place beside her husband and with him entered into all the sacrifices which were the lot of pioneer officers, and they were in very truth pioneers. I think of her in that little mud hut at Howard with literally nothing in the way of comfort, this she endured all to provide some better thing for those who were to follow.

I remember her at Pearson Farm with its pitifully poor furniture, I never came away from visiting there but what I was humbled and impressed with her quiet, peaceful spirit and I feel today that peacefulness which emanated from her. I look at the children, her two officer sons, and how proud she was of them, and I feel that today her children rise up and call her blessed.

We who latterly have watched and known that the sun was gradually setting, have marvelled at her fortitude, at the peace and serenity which was hers, and we have been touched by her gratitude for any little kindness shown or prayer offered. I feel that with Mrs Kirby there was no breaking point, and although she has laid down the sword, she calls us all to carry on. She was so very tired at the end, so God’s finger touched her and she slept. And now we think of those who are left; Mrs Kirby is safe, her pain and suffering are no more, but we think of the Major and the family, of Leonard in Canada and we assure them of our loving sympathy and prayers."

Appointed to Divisional Commander for Northern Rhodesia, present-day Zambia (1954 – 1960)

We left Canada for London where I visited International headquarters. Here Colonel Swinfen, told me I had been appointed divisional commander for Northern Rhodesia. He said The `Army' work in Northern Rhodesia started in 1925 when Colonel Fred Clark and Major Jaynes, went by car to the Zambezi River, crossed over, and walked to Ibwe Munyama where a centre was established on the Northern Rhodesia escarpment. When the centre became isolated from the main road, a new centre was established at Chikankata in 1932 and a Canadian officer, Major George Cowan was appointed its first Divisional Commander. During Leonard and Isabel’s posting, Mazabuka became the new Army headquarters for Northern Rhodesia.

Isabel’s reaction was, “why are we going to a division where the previous divisional commander had been there less than a year, and refused to stay, and the one before him had only remained for 8 months, so before we went to international headquarters that day, I told Leonard that I must fight this battle out.” But the under-secretary said to me, “you are our last hope for Northern Rhodesia, the work is going down and it is costing us so much, therefore the general feeling is that the people are not worth working among, so you go in and either pull the place together or close it.”

Interesting though it is, Leonard and Isabel six years in Zambia are not included here.

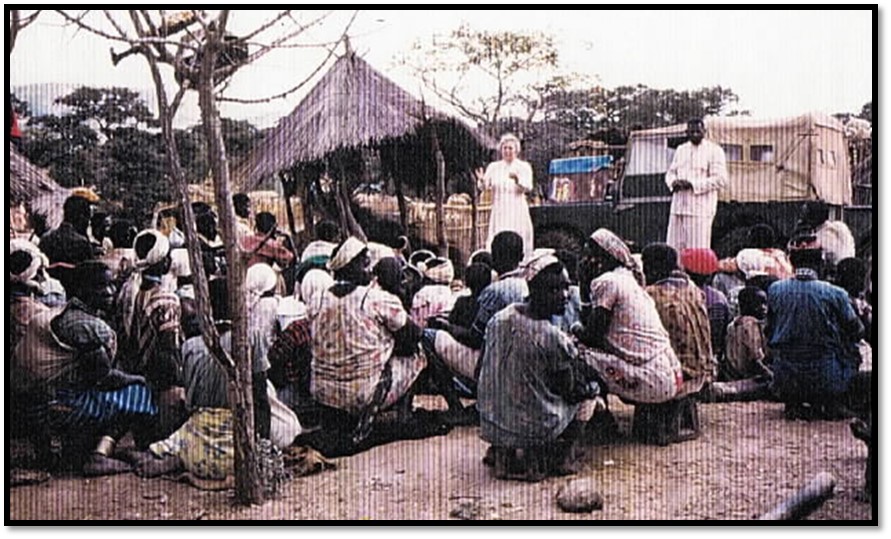

Isabel in a remote Zambian village giving a Sunday sermon

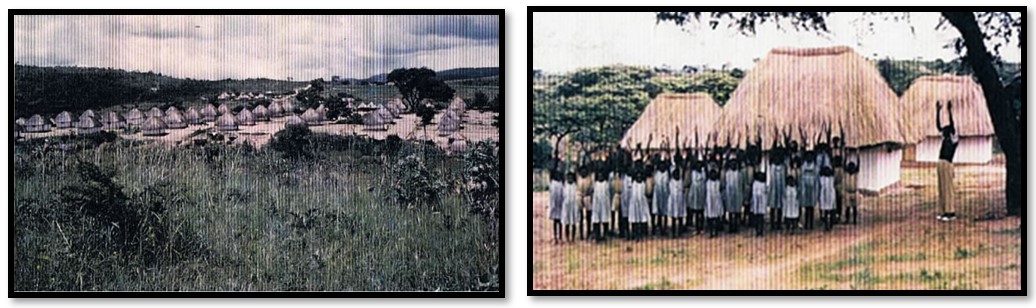

Construction of homes at Chikankata Leprosy settlement

Dad was lonely after Mum’s death and visited my younger brother Andrew at Chikankata. One day he saw the leprosy patients making bricks, but not correctly. So he saw Captain Edith Shangster and asked if she minded him teaching them how to make bricks. She told me about Doctor Gauntlett's plan to eventually replace all the old pole and dhaka huts the lepers were living in with Kimberley brick houses. There was very little money, but he was able to show some of them how to put in the foundations and lay the ant courses. The younger girls carried the small burnt bricks used in the foundations, while the larger girls carried the heavier Kimberley bricks, and the women carried the water. They completed the first ten houses before the rains came but had to stop work until next dry season.

A report in the International War Cry dated about 1960 reads as follows, "In honour of Major Kirby (R) and the great building work he has done at the Leprosy settlement, the school for the leprosy children has been named the 'Kirby School'. As the sun shone on the little white house’s visible from the school, it was hard to remember the pole and dagga huts that had formed the men's part of the settlement before Major Kirby's `retirement' at Chikankata. Since then he has supervised the building of eighty-five houses, teaching many of the men and boys in the Leprosy settlement the art of bricklaying, the value of good foundations and the necessity for an ant course to keep out that constant enemy - the white ant. His consistent example and timely word have taught them more than bricklaying, for they have also seen the value of good Christian foundations for building worthy characters. When the Major finished the 15 houses he is now in course of erecting, his target of 100 houses will be reached and the Kirby School will always stand as a tribute, not only to the Major's craftsmanship, but to his interest in both old and young members of the Leprosy settlement community."

The houses Dad built at Chikankata Leprosy settlement Young Leprosy patients exercising with their teacher

In 1960, after furlough in Canada, Isabel and I sailed for Cape Town and took the three day journey by train to Salisbury and then followed in my father’s footsteps by taking responsibility for the Lomagundi division with our headquarters at Sinoia.

Divisional Commander at Sinoia, present-day Chinhoyi (1960)

Captain & Mrs Andy McDonald, both Australian officers, were temporarily in charge of the division when we arrived and they stayed on to assisting me until their new appointment was ready. They were living in the house Dad had built in 1930! A new house was being built and Dad’s house would become the divisional office and storage rooms as large orders of school supplies were expected. The division had seen many changes since 1930 and I was now teaching a religious knowledge class once a week at my old school!.

It was much easier to get around too, as the roads were now much better than when I had been a child when we used bicycles.

At one centre there had been much disagreement between the teachers and the community. I made it a priority and arranged a visit. On the day arranged there was a great crowd of village people, the village headmen and chief. The teachers gave their version in English which the majority of the villagers could not follow. Then the villagers gave their version, but it did not take long to realise that the headmaster, who was translating, was giving a false translation. Some of the villagers, who spoke some English, were aware the translation was untruthful, saying, “that is a lie, or that never happened.”

The meeting took three hours, then I got up and gave my decision as to what was to happen in future. Captain McDonald said he could not understand my decision, the teachers were unhappy, but of course, the village people were delighted. I explained the problem had arisen through an inaccurate translation, but now all the local people knew I understood Shona.

New problems had arisen at Chikankata, and after five months at Sinoia, we repacked our belongings and moved back to Northern Rhodesia. Major Ron Cox, later Chief of the Staff, was our replacement at Sinoia.

Chikankata Institute, northern Rhodesia (1960 - 1966)

Chikankata is one of the Salvation Army's largest Mission Centres and there is a hospital under the direction of the chief medical officer and an educational centre under the direction of the principal and a large Leprosy settlement with as many as 400 patients in close proximity. The primary school went to Std 3, a co-ed primary boarding school had 200 pupils, taking them from Std 4 to 6 to complete their Primary education. There was also a trade school with a 3 year course teaching woodwork and building. A Secondary School had just been approved by the Ministry of Education with the first class of approximately 30 students.

There was quite a lot of political unrest in the country and some schools had serious student strikes. One of our well-known patients was Kenneth Kaunda, later the President of the Republic of Zambia, who had been arrested a few times on charges of disturbing the peace, or similar offences, in connection with his battle for Independence from Britain and because of the authorities attitude toward him and his followers, they would not go to a government hospital if they were ill but did come to Chikankata Hospital.

We were sad to leave Zambia in 1966 and received many letters of appreciation and thanks from the communities.

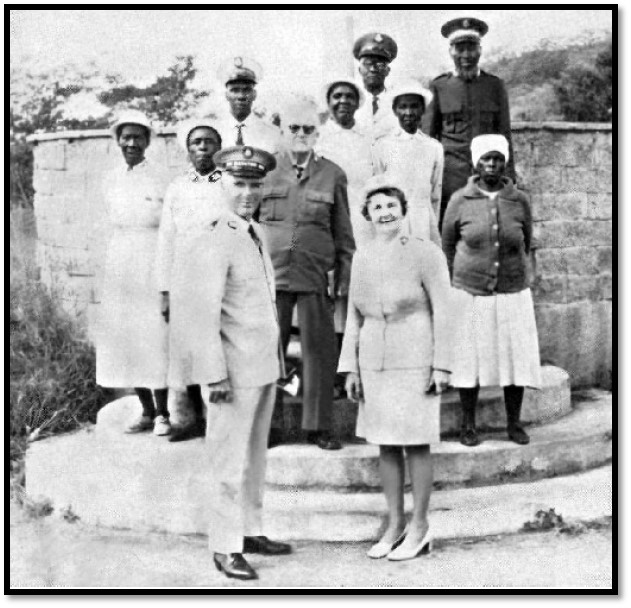

Isabel and I distributing Bibles at Chikankata Greeting Lady Baden-Powell on a visit to Chikankata

Elizabeth gets married

Our daughter Elizabeth wanted to follow in her mother's footsteps and enrolled on a nursing course at the Salisbury General Hospital but after a year, decided nursing was not for her. She was working at a home for handicapped children when she met Ron, who was studying to be a telephone technician. After completing his course Ron returned to the copper belt and Elizabeth managed to get a job nearby. They married in early 1964 at Luanshya and I conducted their marriage in the Methodist Church with the reception at Ron's father's farm.

Home furlough in Canada

Soon after we arrived in Canada we took part in a missionary conference with a large international representation and Dorothy, our second daughter, was enrolled as a senior soldier at the Citadel. We received our appointment as divisional commanders of the Central Mashona division and were delighted because we would be living with my brother, who was a superintendent, my Dad and my sister Rose also lived in Salisbury. We arrived after a very delayed journey by train from Cape Town.

Divisional Commanders of Central Mashona division (1966 - 1967)

We were settling in when I was asked if we could go to Nigeria as the general secretaries. Our main concern was Dorothy who had just started at business school and settled down in Salisbury having joined the Salisbury Citadel Corps and the Songsters and become active in the youth group.

We were sorry to be leaving Rhodesia as we found the work very rewarding and it was a happy place. Isabel had served 28 years and I had served 31 years in Rhodesia as officers.

General Secretaries in Nigeria (1967 - 1968)

We were met at the airport by the territorial commander, Colonel Haakon Dahlstrom and his wife and driven to the Salvation Army compound, where most of the missionary officers lived and where the training college is situated. The general secretary's quarters was a double story house with very large rooms and plenty of windows, because of the intense heat which lasts for most of the year.

Only five days after leaving Rhodesia, Isabel and I left Lagos with very little knowledge of the territory, to go to the east, knowing that civil war with Biafra could come anytime and then we could be completely cut off from headquarters.

We took over from Captain Pat Bird at the Akai Education Centre with responsibility for all the work in the South Eastern State with instructions to get the expatriate staff out of the country and then stay as long as we could. It was clearly a dangerous time for us and the other missionaries of various denominations who stayed in the country. The Nigerian Airforce hired mercenaries to carry out many bombing raids and we were lucky to escape on a number of occasions, finally being forced to move from Akai to Abak with the fighting, although even there was dangerous with the Nigerian Federal army advance. White persons were often shot on sight as mercenaries.

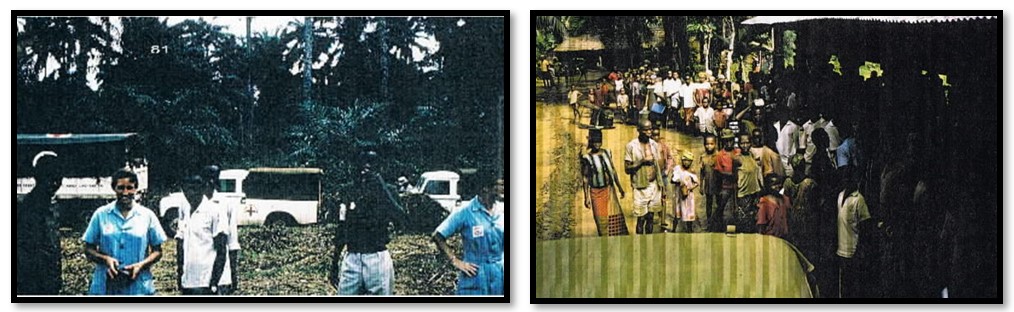

We were arrested with other missionaries who had stayed behind even after being told to quit the country, but various Nigerians were very kind to us all, knowing we were missionaries and in the country to help them. Finally we were flown to Lagos by cargo plane. The Oxfam representative asked Isabel and I to make up a relief team to the South East State with members of the Nigerian Red Cross and we were taken by ship to Calabar and then by road to Abak. The people were starving, many children were orphaned and at the peak of operations we were feeding around 150,000 people.

When the time arrived to leave, we received many expressions of gratitude. Chief Akpan, clan head of the Ikono wrote, "On behalf of my people I write to say thank you for the humanitarian services that you and your team have rendered to us. You have saved many lives, for this God will save your life for you to continue in your efforts to demonstrate practical Christianity acceptable by all men of good taste. God bless you all" and presented me with a Nigerian made briefcase with the words `Colonel Kirby friend of the orphans’ worked into it.

Dad is awarded the Order of the Founder

On 10 December 1972, when Dad was 87 years old, he was awarded the Order of the Founder. The citation reads, “Whereas it has been reported to me that Major Leonard A. Kirby (Canadian) of the Salvation Army has for 52 years given outstanding service, pioneering and fostering our work in Rhodesia and Zambia wielding a remarkable influence for God for over 25 years in active retirement. And Whereas it seems to me that the service of the said Major Leonard A. Kirby as above recorded, was in itself, and in its spirit and purpose, such as would have especially recommended him to the attention and approval of Our Beloved Founder.

Now I hereby appoint the said Major Leonard A. Kirby to be a member of The Order of the Founder and direct that his name be inscribed in the Roll of the Order.” 10 December 1972, General Erik Wickberg

Appointed to Territorial Commander Nigeria (1978)

I only had a few days handover with my predecessor Colonel Dahlstrom. As the territorial commander, Isabel and I met many foreign heads including President Todman of Liberia, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, the Sultan on Zanzibar, The President of Togo, Harold Wilson, Prime Minister of England and President Jimmy Carter of the U.S.A. when he came to Nigeria in April 1978.

Delivering aid after the Biafra War One of the Salvation Army feeding centres for war refugees

Salvation Army Oji River workshop where we made artificial limbs for those disabled in the civil war

At the same time I recognised it was important to have a Nigerian to be his successor and recommended Brigadier Barrika, divisional commander in Lagos.

Farewell to Nigeria

On the 15 June 1978 we said good-bye to the many friends we had made during our ten and a half years in Nigeria and boarded the plane for England, arriving at Heathrow airport next morning, and so ended our years of active service. My entire officership (42 years) had been spent in Africa and Isabel had spent 39 years out of a total of 50 years active officership in Africa.

Dad joined us and together we attended the international congress which was held in Wembley Stadium and then left for Rhodesia for a month’s holiday before returning to Canada.

Canada

At Toronto we attended the Canadian congress meeting where Isabel was presented with a certificate `In Recognition of Exceptional Service, rendered on behalf of The Salvation Army.' The citation on the back reads: "When Mrs. Kirby left a comfortable life in the year 1927, leaving the London Citadel Corps to embrace a life-long career as an officer in The Salvation Army, she undoubtedly did not see her days unfolding in a thrilling, adventure-filled life as a missionary in the vast land of Africa.

On leaving Canada in 1939, after serving as a Registered Nurse in Windsor and Halifax Grace Hospitals, Mrs Kirby commenced a dedicated service of almost forty years in Africa. Married to Colonel Leonard Kirby in 1943, she shared her life with him in giving splendid service to God and to the Salvation Army, concluding her active service in Nigeria.

Who can possibly estimate the worth of a missionary officer, and the extent of the influence of such a life of faith and love. At the International Congress in London, England, Mrs Colonel Kirby celebrated a high and holy moment of joy and achievement when General Arnold Brown presented her with a certificate and badge in recognition of a half-century of loyal and loving service. Such a recognition tells it all."

A new career in retirement in Canada

In November 1978 I worked at the House of Concord, not as the chaplain as had been planned, but as the business manager to sort out some financial problems, under Major and Mrs Jackson who I knew from when he was the divisional commander in Gwelo, present-day Gweru.

Death of my father

Sadly on Sunday 4 March 1979 I received a telephone call informing me that Dad had died in his sleep. This news came as a great surprise because despite being in his 93rd year, he had not been sick, and had carried out his usual visits to the sick and lonely at the B.S. Leon Home and the Andrew Fleming Hospital during the week.

A few of the tributes to him:

`When in the early hours of Sunday March 4th, 1979, Major Leonard Kirby was welcomed home into Heaven, a record of service in this transitory life ended in triumph and Glory to God.'

`A Salvationist of the highest order, Major Leonard Kirby, by his life and service caused many to follow his Lord and bore testimony so often to the saving and keeping Grace of God, the most recent occasion being at the Braeside Social Complex on the Sunday morning before his Promotion to Glory.'

Return to Zimbabwe-Rhodesia[iv] in 1980

Toward the end of January 1980 Commissioner Richard Atwell, the international secretary for Africa, called me and asked if I would take charge of the Salvation Army Rehabilitation programme in Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, as thousands of people who had fled during the conflict were being repatriated in time to cast their vote in the coming elections, and many would require assistance.

But the Salvation Army Rehabilitation Programme did not go ahead, instead the ‘heads of denominations’ in partnership with UNHCR (The United Nations High Commission for Refugees) appointed Christian Care to be responsible for funds allocated to the refugee repatriation programme. I was appointed office manager to replace Captain (Dr) Watt, who was leaving on homeland furlough in Canada. A committee met weekly and consisted of Bishop Hatendi, Dr. Mazobere (Methodist) Father Rodgers (Catholic) and Mercy Musara (World Vision) with the office manager carrying out the decisions of the committee and paying the expenses of the operation.

It was estimated there were up to 200,000 people (150,000 in Mozambique, 25,000 Zambia and 20,000 in Botswana) who had fled from Rhodesia to neighbouring countries during the fighting. On our side of the border the refugees were transported to one of the main reception centres for documentation and could then go straight to their homes, or to a transit centre. About fifty of our Missions became transit centres and approximately 25 percent of the refugees passed through Salvation Army centres.

Our offices at the Presbyterian Church Centre in Salisbury were bombed and wrecked during this time. One of the happiest moments Isabel and I had was to take a truck load of equipment and medical supplies to Tshelanyemba and reopen the hospital which had been forced to close. Ida Sibanda, who was a nurse when we lived there, was back, ready to get down to work, not a single thing had been stolen during the two years that the hospital had been closed, and there had been no damage whatsoever to the building itself. The Corps soon became active again.

The Howard Institute in the Chiweshe Reserve is the Salvation Army’s largest operation and we wanted to help the people rebuild their villages. Isabel and I visited every Corps and listed all the severely handicapped people and old people who had lost homes, well over 100 people needed assistance. I designed a metal frame which could be bolted together to take a metal roof. A factory produced these and the structure gave them a frame with a good roof large enough to divide into two rooms, the walls could be made of grass, poles, dhaka or anything else.

Zimbabwe becomes independent on 18 April 1980

We left for Canada about three months after Independence. I had two very appreciative letters from Garfield Todd, former Prime Minister of Rhodesia and from Bishop Hatendi.

Four months in Ghana

In May 1981 we were asked to relieve Lt Col. and Mrs. Seiler in Ghana whilst they were away on homeland furlough, we were familiar with the country having visited several times. Food and fuel was scarce, our vehicles would be left in a queue outside the petrol station overnight and the local economy was in bad shape. There were six Army clinics in the country and it was difficult keeping them supplied with medicines. During our stay there was a coup and heavy fighting broke out with shelling and small arms and for the following weeks military checkpoints everywhere.

Order of the Founder

In October 1982 Isabel and I are awarded the Order of the Founder, like my parents. The citation reads, "Whereas it has been reported to me that Colonel Leonard F. Kirby has with Mrs. Kirby given unstinting service to Africa, showing courage and resourcefulness, even in times of ill-health and danger, and has in retirement returned to direct relief and rehabilitation operations."

Retirement

The Lord has been very good to us all through our lives, but especially since we retired and we had a few wonderful years together in retirement before Isabel was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Following her diagnosis I gave up working at Booth House (formerly the House of Concord) to help Isabel who become more and more confused and could not be left alone.

My hobby was woodworking for three or four years, and then I took up stained glass, and enjoyed them both. In 1992 Isabel tripped over a mat and broke her hip and needed constant care, but we are pleased she is at home.

I end with the statement that `All through the years His providence has led us' and I pray that all those who read about the wonderful way in which the Lord has cared for us, provided for us, and used us, will know Him as their personal Saviour as we do.

A group of retired Salvation Army officers at Mazowe with Commissioner Richard Atwell and Mrs Atwell. In the centre of the group is Major Leonard F. Kirby O.F. and top right, Major Ben Gwindi, both then aged over ninety.

References

Autobiographical notes written by Leonard Field Kirby

W.D. Gale. One Man’s Vision. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 12, Bulawayo 1976

N.H. Murdock. Christian Warfare in Rhodesia-Zimbabwe. The Salvation Army and African Liberation, 1891–1991. The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge, 2015

M. Nyandoro. The Salvation Army in Zimbabwe 1890-1991, published 1993

Notes

[i] I think Leonard means 1947, i.e. after the royal tour

[ii] The royal tour took place in April 1947

[iii] The 1947 Royal train, 15th Class Beyer Garratt (No. 271, later 350) 4-6-4+4-6-4 in her blue livery, is at the Kadoma Steam Centre. See the article Kadoma (formerly Gatooma) Steam Centre under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[iv] Zimbabwe-Rhodesia was a short-lived state that existed from 1 June 1979 to 18 April 1980,

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: