Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold

- In October 1996 Zimbabwe Scouts at Gordon Park celebrated the exploits of Lt-Col R.S. Baden-Powell's “B-P” exploits as Chief of Staff of the Matabeleland Relief Force in the Matobo Hills a hundred years before.

- Little has been written about the battle of Tshingengoma apart from the original accounts by Sykes, Baden-Powell and Plumer. Perhaps it is because most readers can understand that it was not the victory that B-P made out?

- Tshingengoma was probably the most conventional military engagement fought throughout the Matabeleland campaign. According to B-P, five impis of AmaNdebele were attacked and completely routed and the loss of Sikombo’s stronghold was a major blow to the amaNdebele. However, a closer look at the different accounts of the battle makes this claim questionable.

- The Honourable John Beresford, then a Lieutenant in the 7th Hussars, with a Captain’s rank in the MRF, later Lord 5th Baron Decies, was ambushed by the amaNdebele and nearly lost the seven-pounder guns in his charge. They were saved by Capt. Hoël Llewelyn who used the Maxim gun single-handed and swept away the attackers.

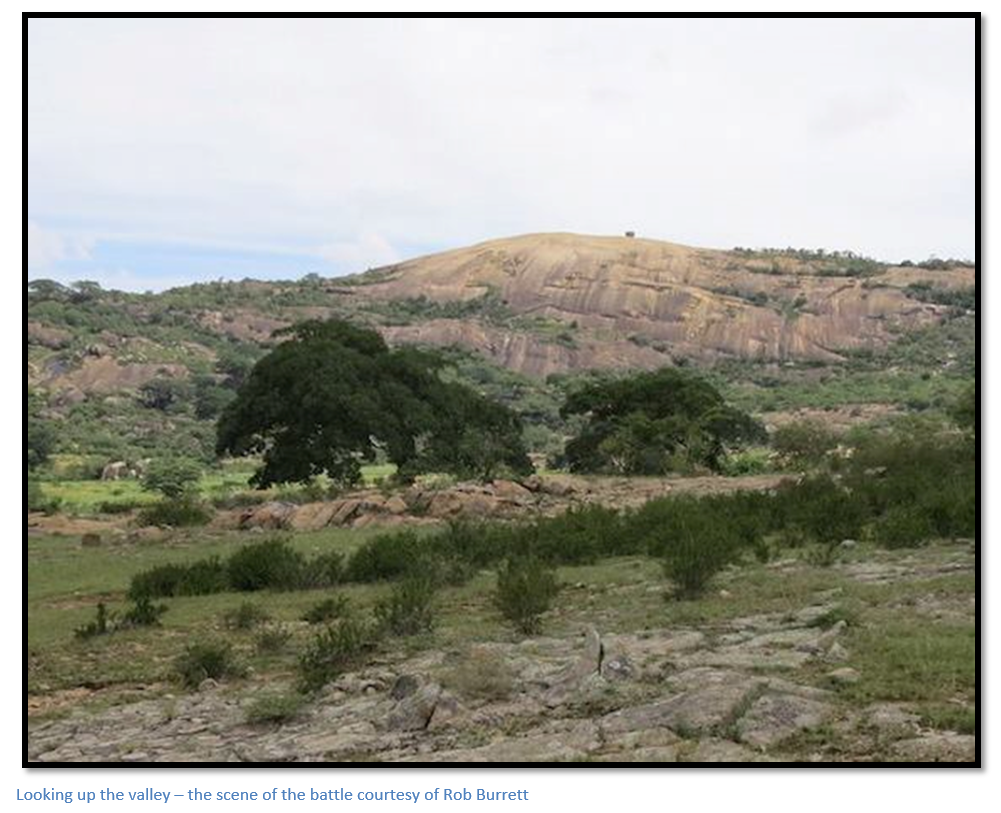

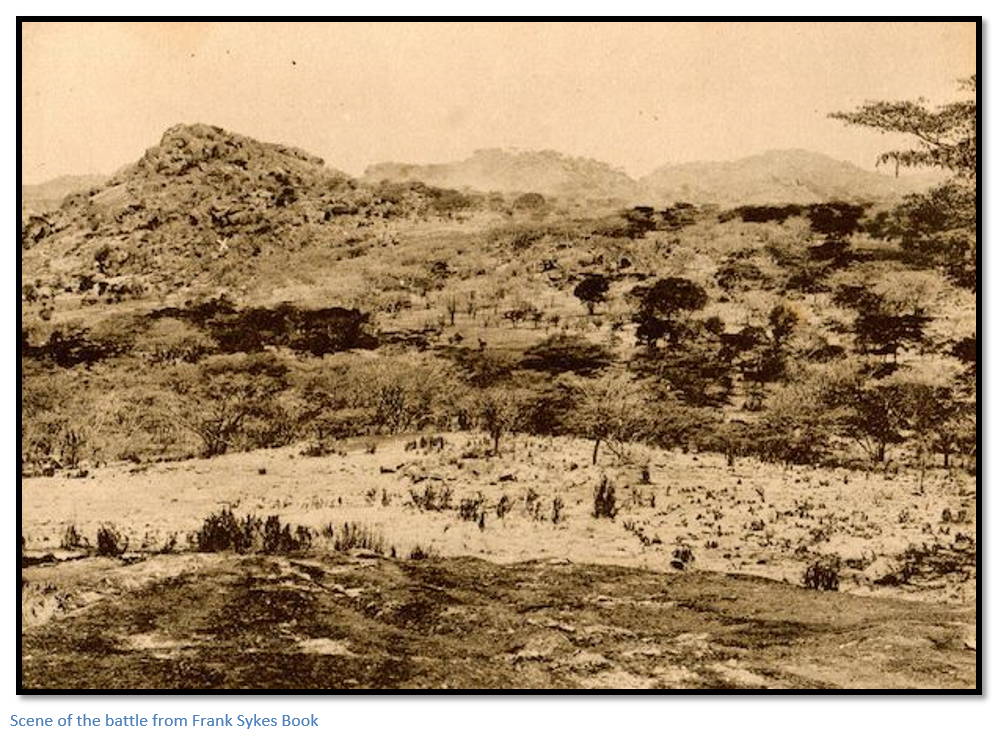

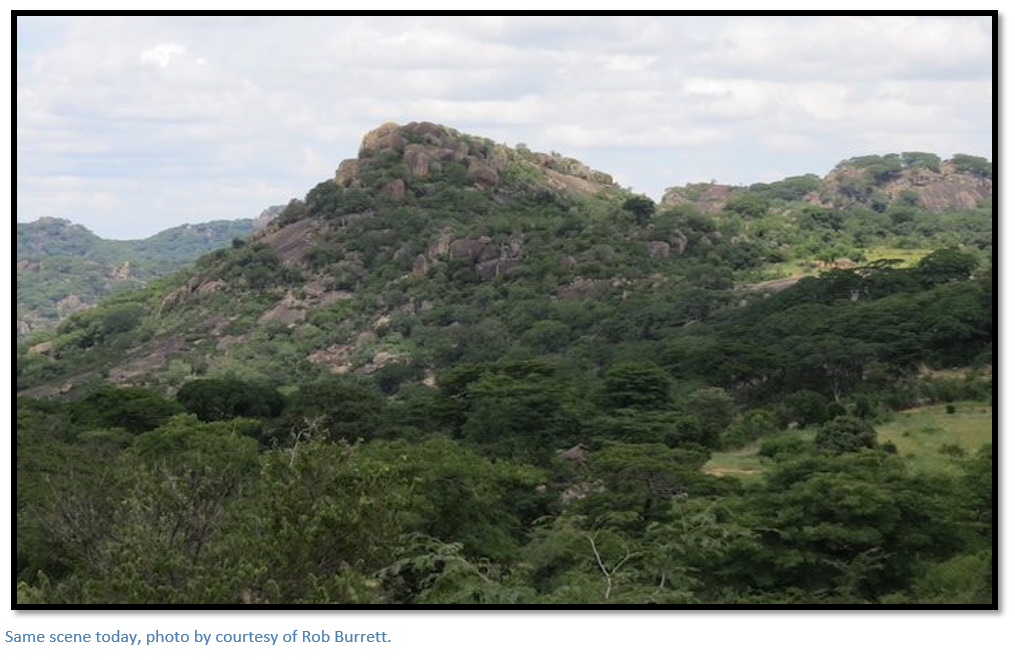

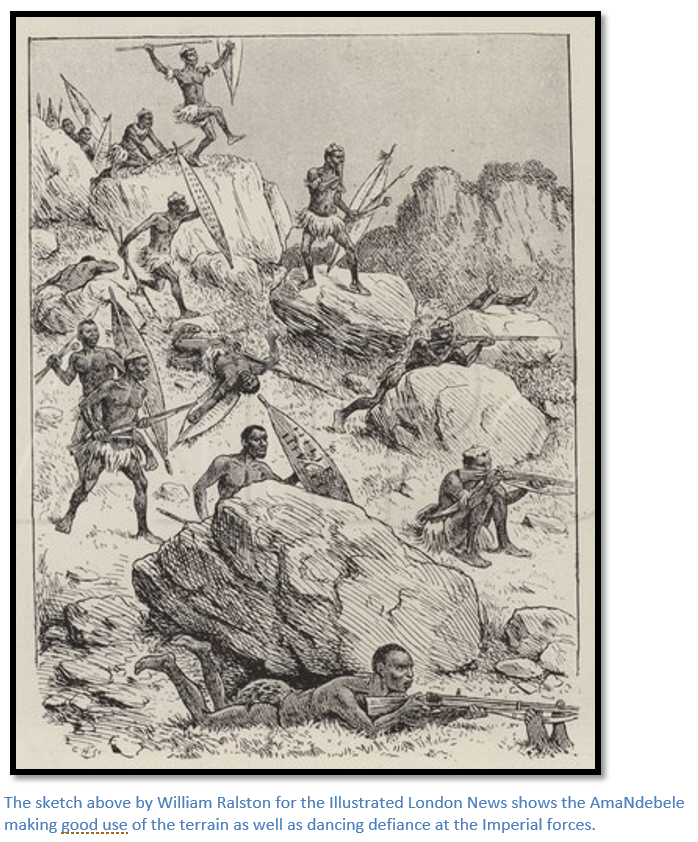

- There is no doubt that the Imperial and local Forces faced a very difficult task in extricating the amaNdebele from the Matobo Hills. Herbert Plumer’s description of the Matobo is appropriate: “an endless sea of kopjes of various sizes, all more or less composed of huge granite boulders, in the interstices of which grow thick bush and scrub and separated from each other in most cases by only extremely narrow and tortuous gorges.”

General directions are the same as for the First Indaba Site. The Indaba site is about 70 kilometres southeast of Bulawayo. From Bulawayo take the A6 towards Gwanda, but turn right at the turnoff just before Mawabeni (57.5 KM peg) Drive the untarred road 10 KM to Esibomvu, turn left down a road 100 metres after Esibomvu Clinic signposted Diana’s Pool 9 KM / Rhodes Indaba site 7 KM. Cross the Nsezi stream following the road, ignore the first road to the left, signposted Tshalimbe Primary School, my GPS directed me down this road to a dead-end. Continue on to where the road forks right to the signposted Indaba site. Take this road, turning a sharp left after 1.5 KM to reach the fenced indaba site on the left-hand side of the road after another 0.5 KM.

For Tshingengoma battle site continue another 2.1 KM until the road makes a sharp right-hand turn and park here. The road is suitable for ordinary vehicles, if they have good ground clearance.

GPS reference: 20⁰27′46.33″S 28⁰51′32.69″E

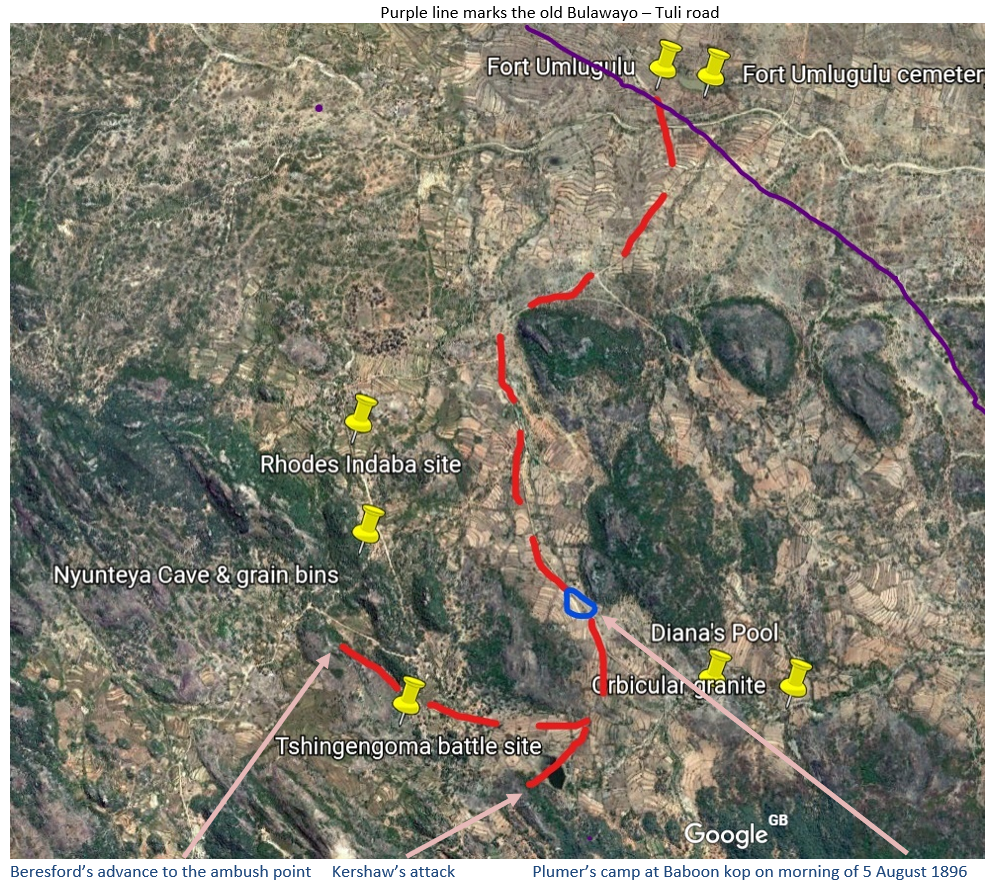

This Google Earth view showing the line of advance of Plumer’s forces to the Tshingengoma battle-site from their base camp at Fort Umlugulu is based on the plan originally drawn by Dr Oliver Ransford in his book Bulawayo: Historic Battleground of Rhodesia.

Background to Tshingengoma battle, the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela 1896

Following a public meeting in Bulawayo on 25 March 1896 convened by the acting Administrator, AHF Duncan there came the realization by the public and the British South Africa Company that the amaNdebele had arisen in rebellion to the European settlors. Quickly a succession of patrols was sent out to rescue the prospectors, traders and miners trapped in remote settlements and then from the beginning of April to the end of May 1896 were followed by a succession of skirmishes around Bulawayo.

Lt-Col. Gifford fought an amaNdebele force at Fonseca’s farm, Capt. “Micky” Macfarlane had two fights on the Umguza River and numerous other small engagements took place almost within sight of Bulawayo on a daily basis. In addition, Colonels Napier and Spreckley took local volunteer forces to Filabusi, Insiza and the Shangani districts.

Colonel Beal’s force of volunteers from Salisbury met up with Napier and reached Bulawayo and a relief column from Fort Victoria and Tuli managed to free Capt. Tyrie-Laing with his small troop of miners and prospectors from their laager at Belingwe and ride into Bulawayo.

Formation and build-up of the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF)

Rhodes was in the country at the time, pushing forward the construction of the Beira Mashonaland railway and telegraphed the British South Africa Company at Kimberley to raise a relief force made up of volunteers to proceed to Matabeleland. Lt-Colonel Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer was put in charge; recruiting began at Kimberley and Mafeking on 6th April, with the exception of 150 men and 163 horses recruited in Johannesburg and 150 Cape Volunteers. However, most were not raw recruits; they had previously fought with the Cape Mounted Rifles, the Bechuanaland Border Police or the Natal Police, and some had taken part in the 1890 Pioneer Column, and even in the 1893 Matabele War.

Mafeking (now Mahikeng) was then the chief town in British Bechuanaland (now the North-West Province of South Africa) although it was outside the Protectorate’s borders until 1965 when Gaborone became Botswana’s capital. Importantly, it was then the northern terminus of the Cape Government Railways; Bulawayo was 936 kilometres away.

A military camp was set up outside the town near the railway station with new recruits, horses, mules, wagons, provisions and equipment brought in by rail. The heavy work of organising the operations of the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) fell under Lt-Col. H. Plumer, a soldier who showed extraordinary capability and good organisational sense.

The first horse was bought on 10 April and the last delivered at Mafeking on 25 April; 1,150 horses from the Free State and Kimberley districts were inspected, purchased and delivered in fifteen days! They withstood the long journey remarkably well and although horse-sickness was widespread, only 88 horses failed to make the journey to Bulawayo.

The MRF marches to Bulawayo

The first troops left Mafeking five days after enrolment showing that no time was lost. They left in batches of fifty for Macloutsie; Frank Sykes in his book With Plumer in Matabeleland gives an eloquent description of the long journey by foot on the road. He says there was always an audience at the morning parade when the riders fully equipped with rifle, bandolier, haversack, water-bottle and spurs attempted to mount their newly broken-in horses. The troop Sergeant-Major impatient of delay, was not to be trifled with; “fall in on the left of the line, are you going to keep us waiting all day?” In would go the spurs, down went the horses’ heads, and then the fun would begin. Buck-jumping exhibitions were a daily occurrence and spills were frequent! Sykes says some of the horses could buck very handsomely, and in the case of a poor rider, a separation between horse and man was soon produced!

Plumer states each group of fifty men had two wagons to accompany them, with a third wagon with every third or fourth party, to carry reserve ammunition, additional stores and sundries. Each man was limited to 20 lbs each (9 kgs.) including two blankets and a waterproof sheet; each wagon carried a buck sail, or tarpaulin, which could be stretched between two wagons during wet weather, and each party had a small consignment of medical stores, as well as cooking utensils, tools for repairing wagons, picks and shovels.

From Macloutsie however, Plumer restricted each man to two blankets and a waterproof sheet and what they could carry in their wallets and haversacks. The remainder of their kit was left at Macloutsie and only brought up to Bulawayo two months later.

Oxen have many advantages over mules; for a start they practically exist on the grass from the veld; mules need grain which had to be cached at stores along the route. In addition, mules could only draw 4,500 lbs (2,041 kgs.) per wagon, whereas oxen could draw 8,000 lbs (3,628 kgs.) but nearly all the oxen had been killed by rinderpest which was still sweeping through Bechuanaland and were practically unobtainable.

Matabeleland Relief Force - departure from Mafeking | ||

Troops | Date |

|

No. 1 | 12-Apr |

|

No. 2 | 14-Apr |

|

No. 3 | 15-Apr |

|

No. 4 | 16-Apr |

|

No. 5 | 17-Apr |

|

No. 6 | 18-Apr |

|

No. 7 | 19-Apr | with two Maxims |

No. 8 / 9 | 20-Apr |

|

Signallers & medical detachment | 21-Apr |

|

No. 10 / Scouts | 23-Apr | with 50 extra horses |

Maxim detachment | 24-Apr |

|

No. 11 / Dismounted detachment | 25-Apr |

|

No. 12 | 29-Apr | mostly BSA Police |

No. 13 | 30-Apr | " |

No. 14 | 01-May | " |

Formation of the Matabeleland Relief Force |

|

|

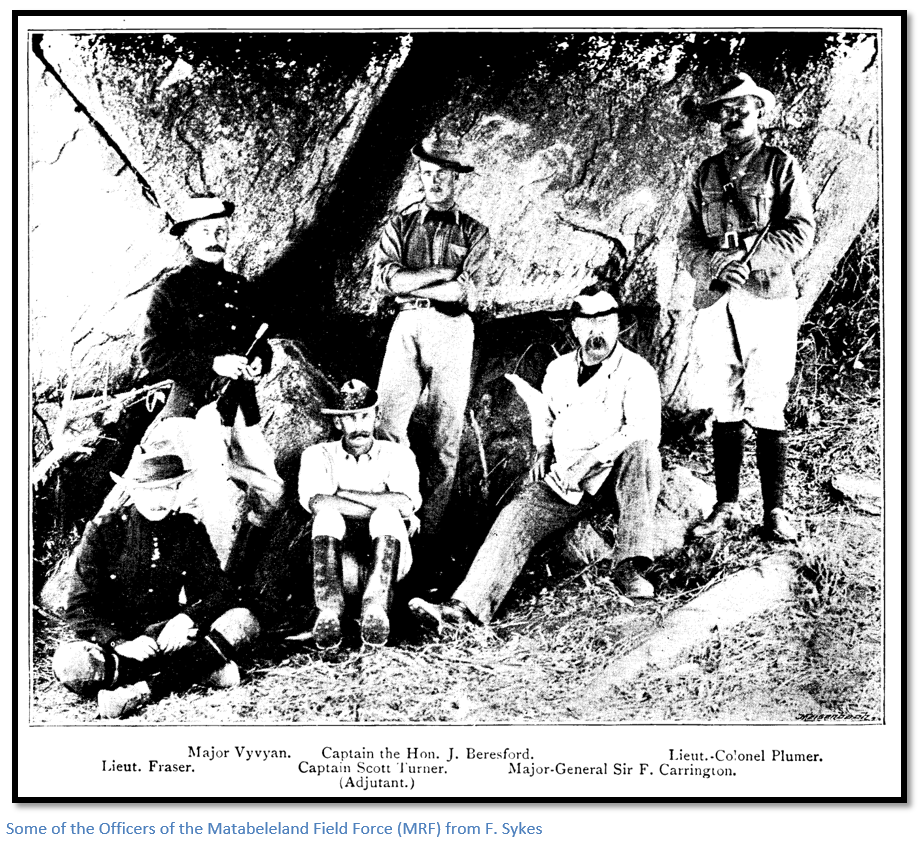

Staff Officers |

|

|

Lt-Col. Herbert Plumer | 2nd Batt. York & Lancaster Regt. | OC |

Major C.N. Watts | Derbyshire Regt., DAAG, Natal |

|

Major F.E. Kershaw | 2nd Batt. York & Lancaster Regt. |

|

Capt. Hon. J.G. Beresford | 7th Hussars |

|

Capt. K. Fraser | 7th Hussars |

|

Capt. H. Scott Turner | Black Watch | Adjutant and Paymaster |

Capt. G.D. Wheeler | Royal Artillery | Maxim detachment |

Capt. B.C. Dent | 1st Batt. Leicestershire Regt. | Signals detachment |

Where there is any conflict in the description of names between Baden-Powell and Plumer; I have picked the latter.

| i/c | Troop 1 | Troop 2 | Troop 3 |

A Squadron | Capt. Bowden | Lieut. Wood | Lieut. Cashel | Lieut. McQueen |

|

| Troop 4 | Troop 5 | Troop 6 |

B Squadron | Capt. Turner | Lieut. Constable | Capt. Satchwell | Lieut. Williams |

|

| Lieut. Oakley | Lieut. May | Lieut. Masterson |

|

| Troop 7 | Troop 8 | Troop 9 |

C Squadron | Major Kershaw | Capt. Fowler | Lieut. Nichol | Capt. Murray |

|

| Lieut. Mathias | Lieut. Forbes | Lieut. Ranstone |

|

| Troop 10 | Troop 11 |

|

D Squadron |

| Lieut. Tomlinson | Lieut. MacGeean |

|

|

| Lieut. Heyman |

|

|

|

| Lieut. Lees |

|

|

Maxim detachment | Capt. Wheeler | Lieut. Pyke | ||

|

| Lieut. Michell | ||

Signalling detachment | Capt. Dent | |||

Medical detachment | Dr Michell | |||

| Dr Morris |

Between the Shashe River, the boundary to Matabeleland, and Mangwe; the squadrons did not march at night because of the thick bush and proximity of the amaNdebele. On the march, one Troop would act as advance guard; another as rear-guard and a third with the wagons; there were “Cossack posts” at the midday halt and pickets at night when a small laager would be formed within the wagons.

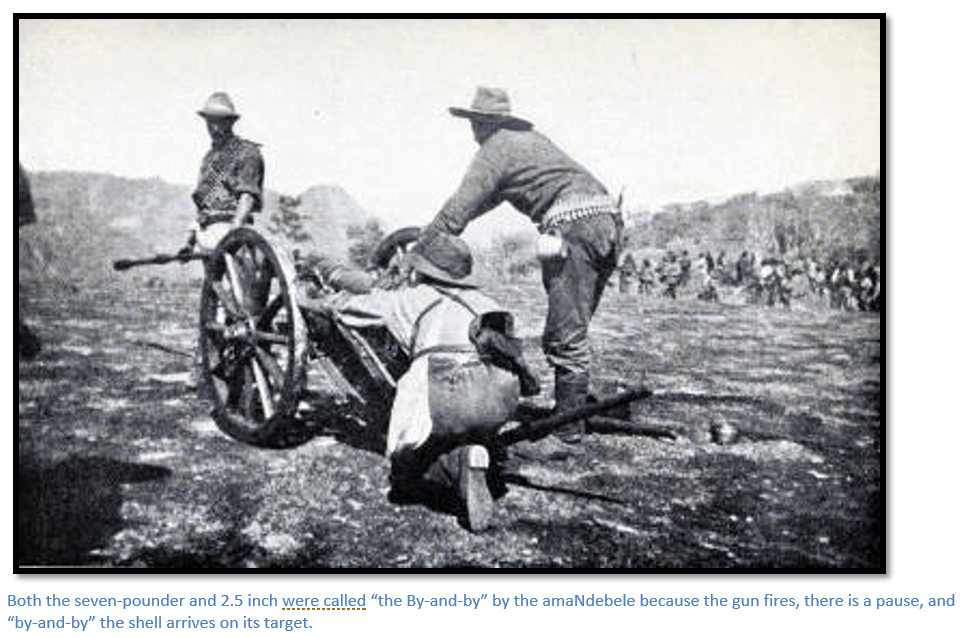

On the morning of 24 April, to the delight of Bulawayo’s citizens, the long awaited-for MRF marched into Bulawayo. Once the MRF were dismissed from the parade, old comrades recognised and greeted each other with “Plumer’s men” eager to learn details of the fighting that had already taken place from locals. Sykes says the AmaNdebele were still a presence around the town. They would appear on the ridge summits within five kilometres of the town and provide target practice for the seven-pounder guns. Once the guns had found the range, the shrapnel shells bursting overhead suddenly reminded the amaNdebele of an appointment a few miles further away!

First skirmishes by the MRF with the AmaNdebele

With the arrival of Plumer and his staff things got quickly under way with an operation to liaise with Major Watts on the Umgusa River at midnight on 24 May. Major Watts came into contact with the amaNdebele at about 3am and heavy firing, including the Maxims commenced. At dawn the combined force moved forward and again encountered the amaNdebele; a skirmishing line was formed, and the mounted forces charged forward, whereupon the AmaNdebele retreated and melted away into the heavy scrub. Further skirmishing took place on the Khami River until sunset on the 25 May.

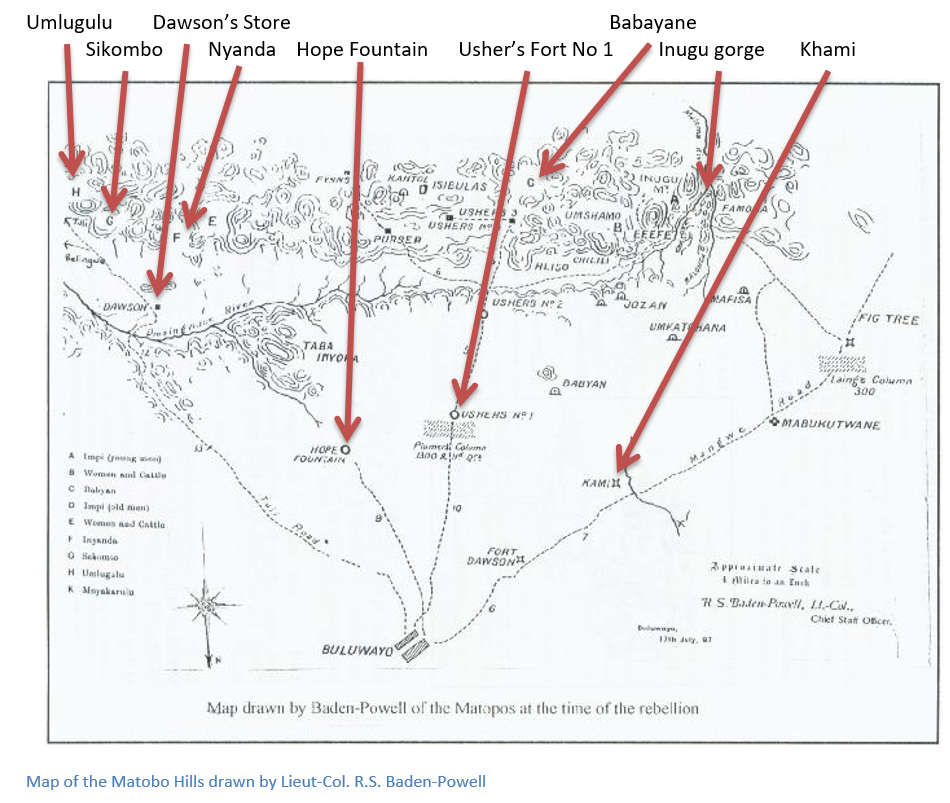

After further reconnaissance failed to show an AmaNdebele presence, the MRF force moved on the 29 May to Hope Fountain Mission and remained here until 4 June when they marched back to Fort Khami, shown clearly on the map by Baden-Powell below.

Their next assignment was a twenty-day patrol down the Gwaai River which began on 5 June; the column comprising 450 Troopers, three Maxim guns on travelling carriages and sixteen transport wagons. Most of the kraals encountered were found to be deserted and although amaNdebele scouts were frequently seen, the main amaNdebele Regiment gave the patrol the slip and made for the Matobo Hills.

Frank Sykes shrewdly comments that it was hardly surprising the amaNdebele were never taken unawares; from reveille before daybreak until lights out at 8:45pm, bugles were sounding out calls throughout the day and at night rockets and star shells lit up the sky for miles around! The line of advance was marked by dozens of blazing kraals on both banks of the Gwaai River and at night the rockets and burning grass advertised the column’s presence very clearly and the only real casualties were stragglers, or amaNdebele scouts caught by small patrols.

Near the Gwaai River a surprise attack was planned and the patrol under Major Watts cautioned not to talk with all orders to be given in whispers, and no smoking permitted, or fires lighted. It seemed certain that the amaNdebele would be drawn into a fight, but at the last minute Major Watts without thinking gave the order for the bugler to sound a call and all surprise was lost!

The cold nights and stealing of personal kit, lack of tobacco and monotonous rations resulted after the end of the Gwaai patrol in about a sixth of the men requesting their discharge; but Plumer explained in a speech to the troopers on parade that they had signed on until their services were over.

The next engagement between the MRF and the amaNdebele took place at Ntaba zika Mambo [covered in a separate article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Almost all the MRF left Bulawayo on 28 June, the force comprising about 1,200, the largest made up of any engagement in the country. The stronghold was to be reached by a twenty-five-kilometre night march from Inyati Mission (now Inyathi) with the attack planned to start at dawn on Sunday 5 July; the amaNdebele were estimated at between 1,500 – 2,500 armed men. After a stiff resistance the amaNdebele deserted their rocky kopjes and the column started back on Tuesday 7 July, arriving back at Usher’s No. 1 farm south of Bulawayo on 13 July.

The battle zone moves to the Matobo Hills

Following the battle at Ntaba zika Mambo the large amaNdebele fighting force estimated at 5,000 by Sykes, now became broken up and rendezvoused south at various points within the Matobo Hills. The iButho of Babayan and Dhliso occupied the central Matobo position, the western Matobo were under the Indunas Nyanda (a brother of Lobengula) Sikombo and Umlugulu, and the eastern Matobo under the command of Mabiza and Hole. Against them General Carrington had about 1,100 of the MRF backed up by 160 Cape Volunteers and an amorphous collection of amaNdebele levies and ‘friendlies’ under the command of Johann Colenbrander.

Frank Sykes in his book With Plumer in Matabeleland has a chapter on John Grootboom and his significant contribution to the campaign. Grootboom was from the Cape and provided invaluable intelligence to Plumer as he was able to infiltrate the amaNdebele forces, especially at night, and listen to their conversations and learn their plans and dispositions. His scouting into Ntaba Zika Mambo before the main attack provided vital intelligence and is told in the article on this battle.

Although John Grootboom respected Baden-Powell’s method of going into the Matobo with a sole companion for scouting purposes; he called him “Colonel Baking-Powder;” Plumer’s fighting tactics came in for fierce criticism from Grootboom. The MRF tended to fight the fight during the day and then return to their laagers at night and Grootboom thought that was no way to fight the amaNdebele. He continued: “they go out in the open and let the Matabele shoot and shoot, and down they fall. I saw one man walk out from behind a rock, and as he did so, a Matabele shot him through the head. But you don’t see Colonel Baking-Powder do that. If they want to shoot him, they must go after him, catch him out from where he hides. He knows better than to stand up to be shot at.”

Initial contacts with the amaNdebele result in stalemate

The amaNdebele could not be expelled from the Matopos in a single battle; their tactic was to slip away as soon as they lost the military advantage and move into another set of rocky kopjes. The MRF fought a number of separate battles, each involving frontal assaults on rocky and thickly defended positions. Heavy losses were suffered by both sides, and no material advantage gained by either side. These battles are all described by Sykes, Baden-Powell and Plumer in their books.

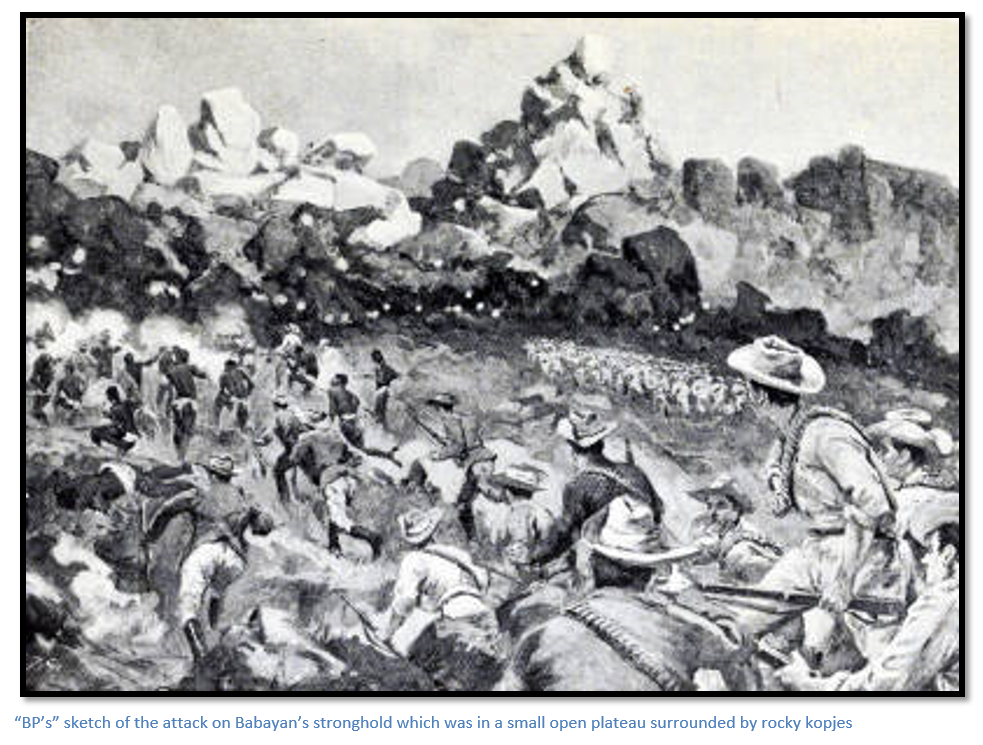

On the 19 July the MRF under the personal command of Major-General Sir F. Carrington made a night march on Babayan’s stronghold known as the Nkantola in the mid-section of the Matobo Hills with the intention of attacking at dawn. The main attack force consisting of 800 white troops and the Cape Volunteers would attack from the north; a smaller flying column of 170 whites and 300 ‘friendly’ irregulars under the command of Capt. Tyrie-Laing was to attack from the west.

After marching for two hours, a halt was made for four hours with the men attempting sleep in the chill winter air, before moving on again. At first light battle commenced with the seven-pounders shelling the stronghold, but Tyrie-Laing’s forces did not succeed in co-ordinating their attack. The Cape Volunteers fought well, driving the amaNdebele out of a kraal in the valley and storming Babayan’s stronghold which consisted of an intricate labyrinth of caves, strengthened by dry-stone walling; but the ‘friendlies’ lost their heads firing wildly and became a danger to everyone.

Little of military advantage was gained and the amaNdebele vacated their positions to fight another day. They had learned from 1893 that to attack the Maxim guns which they named “isi-kwa-kwa” in the open was a mistake and had adapted their tactics accordingly. Here the MRF had Sgt Worringham killed, Lieut. Taylor wounded, four Cape Volunteers killed and ten wounded.

Worringham, Frederick C. Sgt | MMP | Babayan’s kraal | KIA | 20th July 1896 |

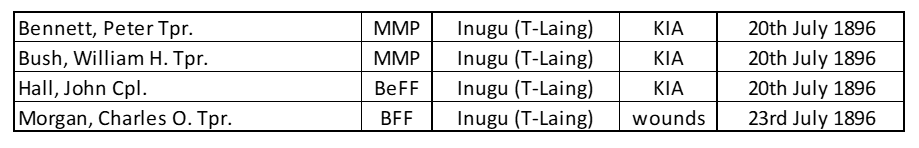

Capt. Tyrie-Laing had entered the eastern Matobo Hills in the afternoon of the 19 July and chosen a poor site to laager, later known as “Laing’s graveyard,” where a long narrow gorge widened into a valley under Inugu Hill. The laager site was overlooked on two sides; the amaNdebele under the Indunas Mabiza, Inkonkebella, Holi and Dhliso launched an entirely predictable attack at dawn, the ‘friendlies’ panicked and ran across the laager’s line of fire with about thirty killed and wounded. The amaNdebele charged within 20 metres of the wagons before being turned back by case shot from the seven-pounder. The Maxim gun attracted special attention from snipers with four men being wounded on it before Capt. Hopper took charge. Casualties included:

Nine troopers were wounded, some seriously, twenty-five friendlies were killed or missing, eighteen wounded and eighteen horses and mules killed. B-P says a hundred amaNdebele were killed but offers no evidence to support this figure.

On the night of 24 July Capt. Nicholson with 250 mounted men, 200 Cape Volunteers, two seven-pounders and two Maxims left for the scene of Tyrie-Laing’s fight at Inugu. Frank Sykes says the object of the visit was to teach the amaNdebele in that area a lesson, but it was subsequently found out that they were not as amenable to instruction as they might have been.

Advancing along the same track as Tyrie-Laing’s forces six days previously they were attacked in Inungu gorge by an invisible enemy who fired from the heights. Lieut. Henry Colenbrander led his native contingent up the right-hand side of the gorge but was unable to dislodge their attackers. Casualties were:

Bern, William Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27th July 1896 |

Cheves, Laurence Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27th July 1896 |

Porter, Joseph Kirk Cpl.* | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 3rd August 1896 |

Two troopers were seriously wounded and Colenbrander’s contingent lost two killed and four wounded. Corporal JK Porter is not listed on the Fort Umlugulu cemetery memorial. It was with a great sense of relief that Nicholson’s force was not attacked again as they made their way along the valley floor commanded by high rocky ground.

The Bulawayo press stated a considerable number of amaNdebele were killed; the amaNdebele themselves when asked later said only two died on the spot. But the press was already beginning to question the military tactics saying: “Carrington has to choose between two alternatives – either he must storm the hills and drive the rebels out at a heavy sacrifice of valuable lives, or he must build a chain of forts at enormous expenditure, and so, in course of time, starve them into submission.”

The battleground moves to the western Matobo

On 30 July General Carrington left for Bulawayo and handed over command to Lieut-Col Plumer. The next day the column marched from Usher’s Fort No 1 taking a route through the Matobo whilst the transport took a longer route around the hills.

Colonel Plumer's Column strength for the battle at Tshingengoma | ||||

Officers | Men | Horses | Guns | |

Matabeleland Relief Force | 42 | 477 | 369 | 3 Maxims |

Matabeleland Mounted Police | 11 | 107 | 47 | 1 Maxim, 1 Hotchkiss, 1 7-pr, 1 2.5 inch |

Royal Artillery | 2 | 26 | 3 | 2 2.5 inch |

Colenbrander's Corps | 6 | 183 | 8 |

|

Robertson's Cape Volunteers | 4 | 102 | 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total | 65 | 895 | 431 |

|

The following day the column had a small engagement with the amaNdebele at the head of the Mtshabezi valley following some reconnaissance work by B-P. Major Kershaw led C squadron of the MRF who had a brief and inconclusive skirmish with the amaNdebele before they retreated into the deep caves to escape the seven-pounder’s shells.

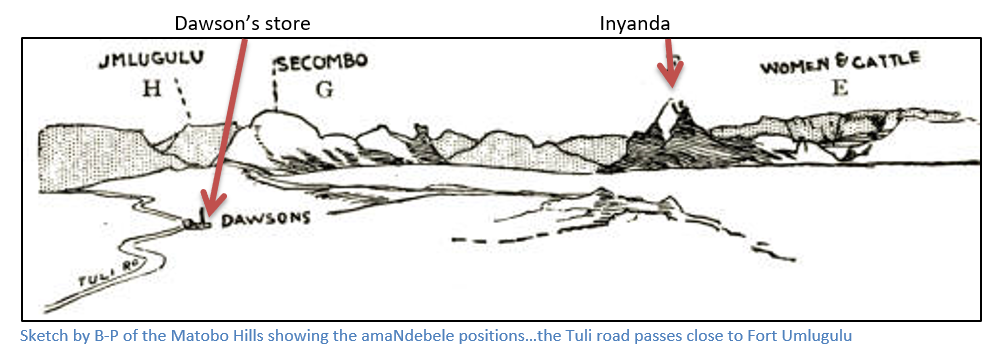

The column then moved up the Tuli road to Dawson’s Store where they met the transport wagons and rested for a day.

On 2 August the force went looking for a fight at Nyanda’s stronghold; first shelling the main kraal and then sending flanking parties to the left and right of the main kopje and finding caves at the rear defended by dry-stone stockades, which contained grain stores of maize, corn, monkey-nuts and rice stored in large woven baskets which were seized.

Major Kershaw went up the Tuli road towards Bulawayo to Spargo’s store to fetch the wagons. He reported on his return that the ‘friendlies’ had proved very disappointing in action and in disgust at their behaviour their rifles had been taken from them and loaded onto a wagon to be sent back to Bulawayo. In unloading the rifles at Spargo’s store, Trooper Little pulled one out by the barrel which was cocked and loaded. The gun went off killing Trooper Little and wounding Troopers Champion and Sieberhagen.

Little, Edward R. Tpr. | MRF | Spargo store | accident | 3rd August 1896 |

On 4 August the column marched to the Fort Umlugulu site, then called Sugar-bush Camp, on a ridge overlooking the Nsezi River. [There is an article on Fort Umlugulu on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] On the way B-P captured an old lady, Umzava, a niece of Mzilikazi, who had been carrying supplies to Umlugulu and confirmed that there were five Impis in the hills around and gave the information that were tired of fighting as they could not plant their crops and were getting increasingly distrustful of the Mlimo who had predicted the Europeans would all die of rinderpest.

B-P reported to Plumer that he thought he had located a considerable body of Sikombo Mguni’s men only eight kilometres away and Plumer quickly decided to attack them early next morning.

The Battle of Tshingengoma

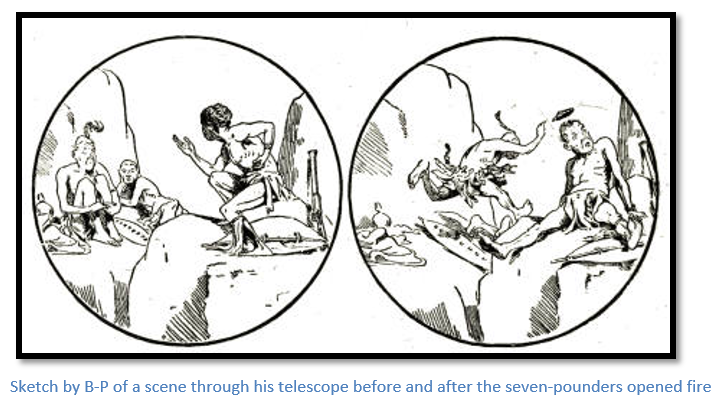

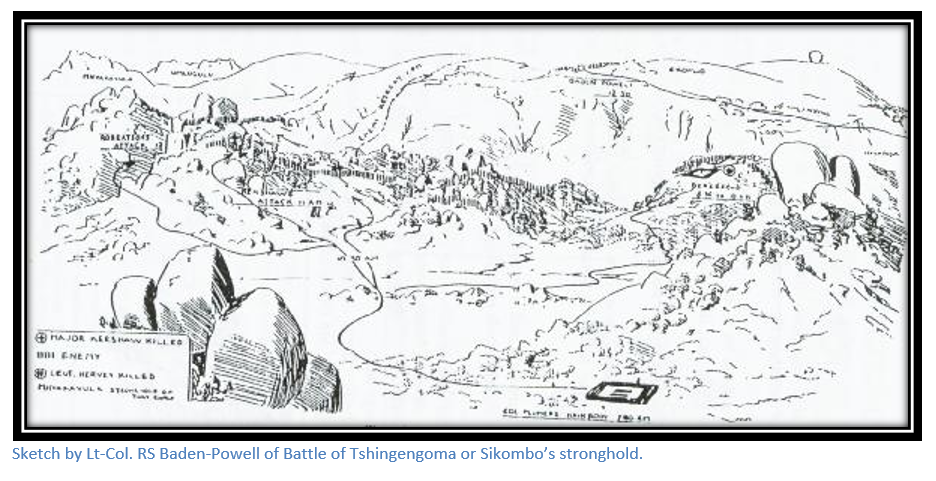

The following day a force of 760 comprised of MRF, some Police, Coope’s Scouts, Robertson’s and Colenbrander’s Cape Volunteers, two seven-pounders, Maxim guns, a Hotchkiss and rocket tubes left at 4:30am to attack Chief’s Umlugulu and Sikombo Mguni’s strongholds on the east of the Matobo Hills leaving just B Squadron with two Maxims and a seven-pounder at Fort Umlugulu. They crossed the Nsezi River in the dark and skirted the Matobo Hills with “B-P” acting as guide for about three kilometres before halting at Baboon Rock at 6:15am. The force then moved forward into a space between two bald kopjes opening into a valley in front of Tshingengoma. B-P describes the back of the valley being dominated by a single high ridge of smooth granite and having five offshoots of wooded hills running down into the valley like fingers from a ridge of knuckles; the rocky tips of the fingers formed the strongholds for the amaNdebele.

Tactically it made sense to get the two seven-pounders on a commanding position on the nearest finger on the western side of the valley in order to bring an effective fire on each of the strongholds and clear the way for the attacking troops. Accordingly, at 7:30am Colonel Plumer ordered all the dismounted men of the MRF and MMP (138) forward under Capt. the Hon. J. Beresford with the seven-pounder guns to take up a position on a hill to the west of Sikombo’s main position, subsequently called “case-shot kopje,” which when captured would enable the guns to shell most of the surrounding area prior to the main advance.

The two local guides declared they did not know which way to go and Beresford selected what he thought was the best path. Progress up the broken ground on the right-hand side of the valley was slow and about halfway up the hill, at a small plateau a halt was made, when Beresford’s force was surprised by a large number of amaNdebele who had crept up on them unobserved from the other side of the ridge and concealed themselves and then began to fire at short range from the cover of caves and boulders. The two seven-pounders had been positioned without an advance guard and this nearly ended in disaster as they were rushed by the amaNdebele; the Artillery Troop only just managed to limber up the guns and fire case shot at point-blank range to halt their charge.

To the right of the seven-pounders Lieutenant Hervey was ordered to attack, but as he stood on a rock waving his men forward, he was shot and mortally wounded. He was laid on a stretcher in the shelter of two large boulders, telling his men to continue on fighting. Battery Sgt-Major Ainslie, who took his place, was killed here immediately afterwards. [see the article on Hubert Hervey in Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Lieuts. McCulloch and Fraser were wounded as the amaNdebele began firing from behind rocks and trees at close range, but they continued to fire the seven-pounders. To the left of the seven-pounders on the hill slope Captain Hoël Llewelyn operated the Maxim gun single-handed and swept away his attackers at 90 metres and stopped a further charge; Tpr Holmes seeing Llewellyn unsupported ran to his assistance and was mortally wounded in the thigh and died four days later. Several bullets hit the Maxim and Llewellyn was struck in the face by a stone splinter, Colonel Plumer praised him in his despatches: “Hoël Llewelyn who worked and managed his gun admirably under heavy fire.” For more details on his career see the article by BH Taylor in Heritage No 18 who quotes several newspaper articles. For example, the Cape Times wrote on 5 August 1896: “Captain Llewellyn practically saved the gun by his smart and plucky action. He was one time completely alone. The fire was heavy and well directed…Captain Llewellyn’s Maxim fired 900 rounds…” and on the 6 August: “on the left of the lie the rebels charged up to five yards of the Maxim and were shot down at that range by Capt. Llewellyn who stuck to his guns with great bravery.”

Plumer says Llewellyn did “splendid service” and recommended him for a Victoria Cross award for his coolness under fire, but although he received the BSA Company campaign medals for 1893 and 1896, he was not awarded the Victoria Cross probably because as the title of Plumer’s book on the campaign suggests, it was an ‘Irregular Corps.’

As soon as the firing began the ‘friendlies’ carrying the Hotchkiss dropped the pole on which it was hung and ran off; part of the gun could not be found, and it was never brought into action.

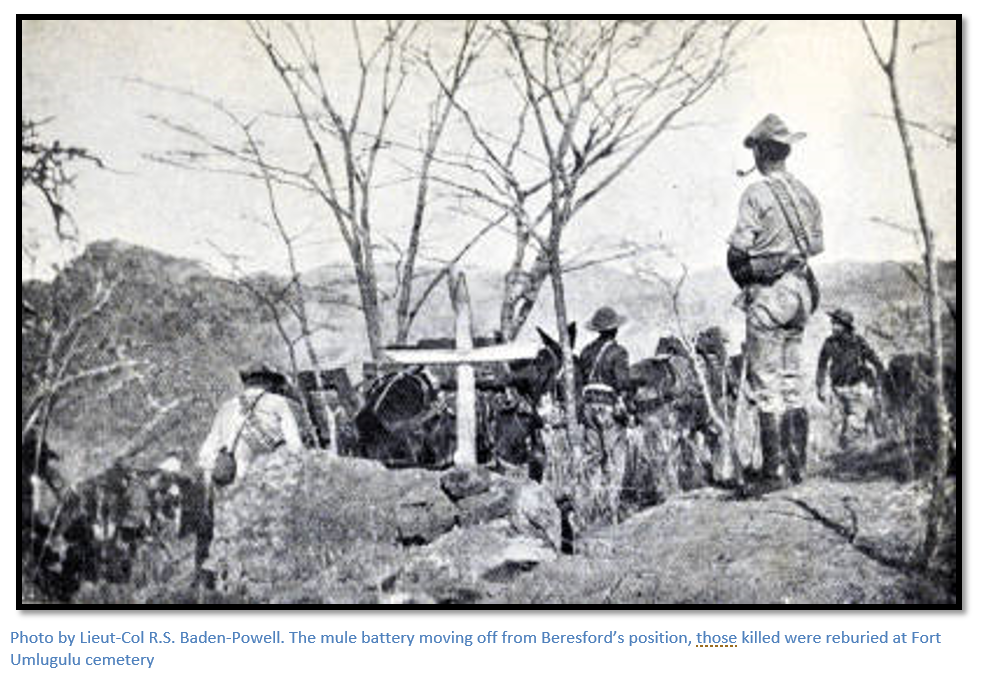

Rodney Tourle tells me that the small x on the above photo marks the spot where Sergeant Innes-Kerr was shot and killed and that almost directly above the x but closer to the summit was where Major Kershaw and Sergeant-Major McCloskie were killed shortly afterwards.

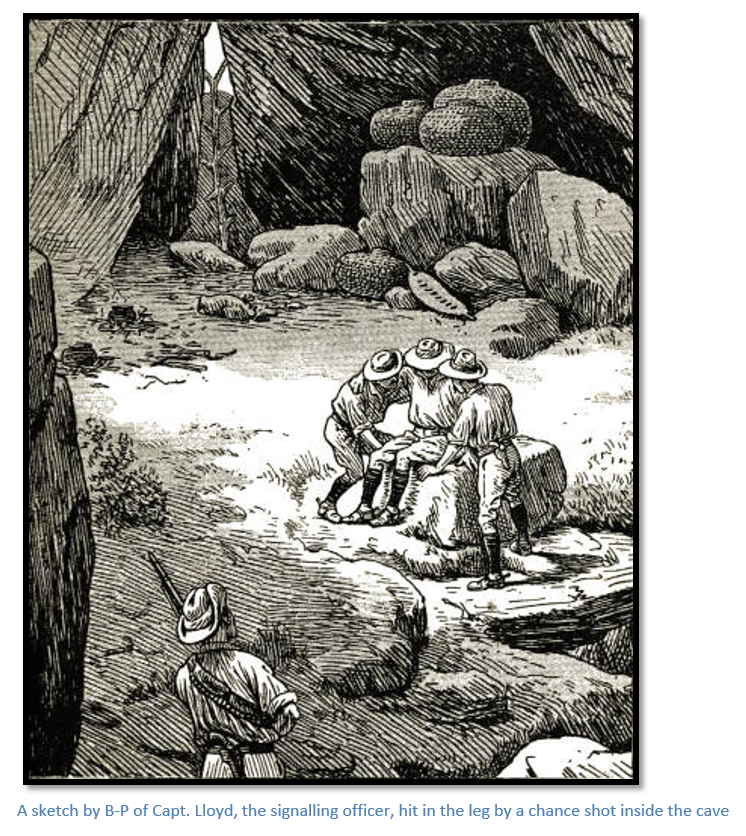

At 7.30am Colonel Plumer's and the remainder of the forces still halted at the head of the valley could hear, but not see, the heavy incessant firing from Beresford’s Maxim guns and the two seven-pounders. When sounds of the engagement became more intense, Capt. Jesser Coope with his Scouts was sent by Plumer to assess the situation and reported back at 10:30am that Beresford’s force had been heavily attacked for over an hour, with Hervey severely wounded, and needed reinforcements urgently.

The MRF’s A squadron under Capt. Bowden and the MMP under Capt. Nicholson and two Maxims were despatched to Beresford’s support; at 11am soon after a war rocket was fired and caused the whole battlefield to fall silent, the sound of a kudu horn was heard from Sikombo’s lines and Col. Plumer ordered Coope’s Scouts forward with Colenbrander’s and Robertson’s Cape Volunteers. The Cape Volunteers ran forward with every man firing and under their combined assault the amaNdebele attacking Beresford retreated to the top of the kopje and then fell back onto the next ridge, or finger.

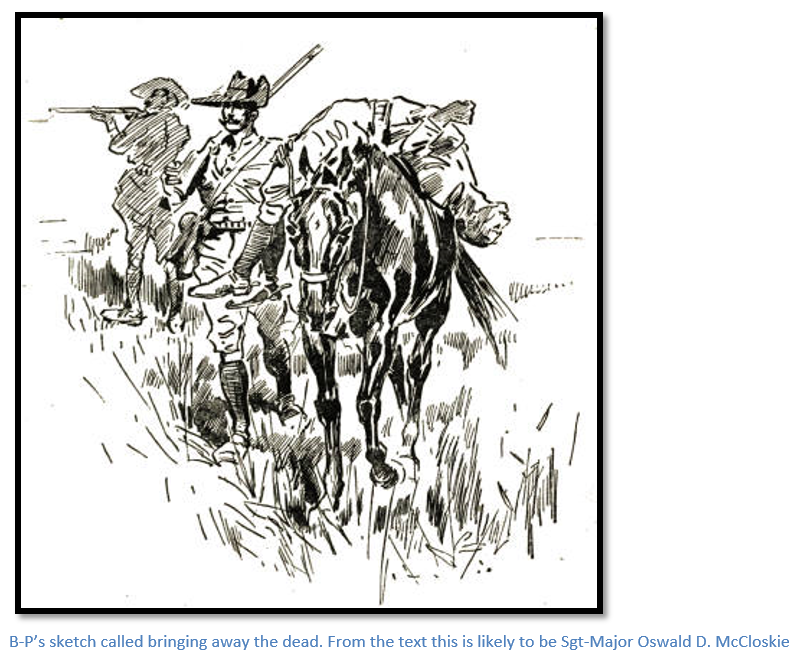

The three mounted MRF squadrons (C, D and E) led by Major Kershaw and Captains Fraser and Drury galloped across mealie fields to the foot of Malumika Hill where they dismounted, leaving their horses tied up at the base of the kopje, and commenced climbing the hill on foot. B-P took Coope’s Scouts with him and worked around the flank and rear to assess the situation. A heavy fire opened up on the climbing men. Major Kershaw followed by his Sergeant-Major and troopers had almost reached the entrance of the main cave below the summit when he was shot twice and fell mortally wounded; seconds later Sergeant-Major McCloskie was shot dead.

At Beresford’s position, Sergeant Innes-Kerr of the Maxim detachment stepped out to shoot at a sniper behind a nearby boulder and was himself killed. It took an hour for D and E squadrons to push back the amaNdebele, supported by cross-fire from Beresford’s position, and as they retreated Sergeant Gibb was shot through both legs and soon died; his body being carried back to “case-shot kopje.”

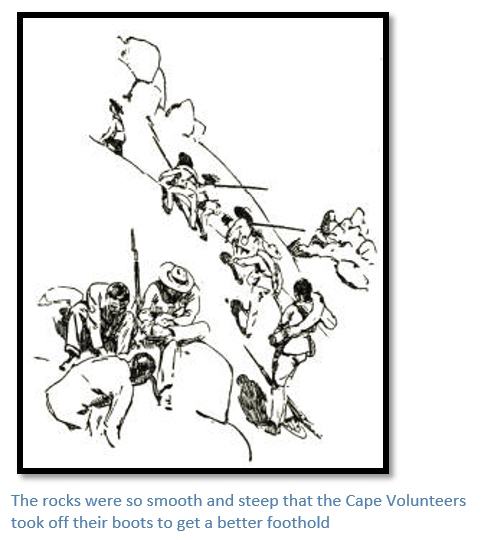

Major Robertson’s and Colenbrander’s Cape Volunteers attacked at 12am up the far side of Sikombo’s Hill and by advancing steadily under cover they managed to push back the defenders. Some of the slopes were so vertical they removed their boots to get a better footing on the granite and as they gained the heights the AmaNdebele stole away and out of sight.

B-P and Coope’s Scouts moved through Beresford’s position, before continuing up the finger to the knuckles via a very steep path which they negotiated single-file leading their horses. Once they reached the top of the ridge they saw that the amaNdebele were retreating to the next ridge. From this spot B-P had a fine view of the entire battlefield and signalled to Col. Plumer for reinforcements to pursue the retiring amaNdebele, but the reply came that every man was needed in a final attack into the kopjes in the valley itself.

The Cape Volunteers had managed to work their way onto the fourth ridge or finger with some hard fighting. The MRF and Police attacked the central positions and quite soon the amaNdebele were streaming off the ridges in retreat, pursued by Maxim and seven-pounder fire wherever they made a good target.

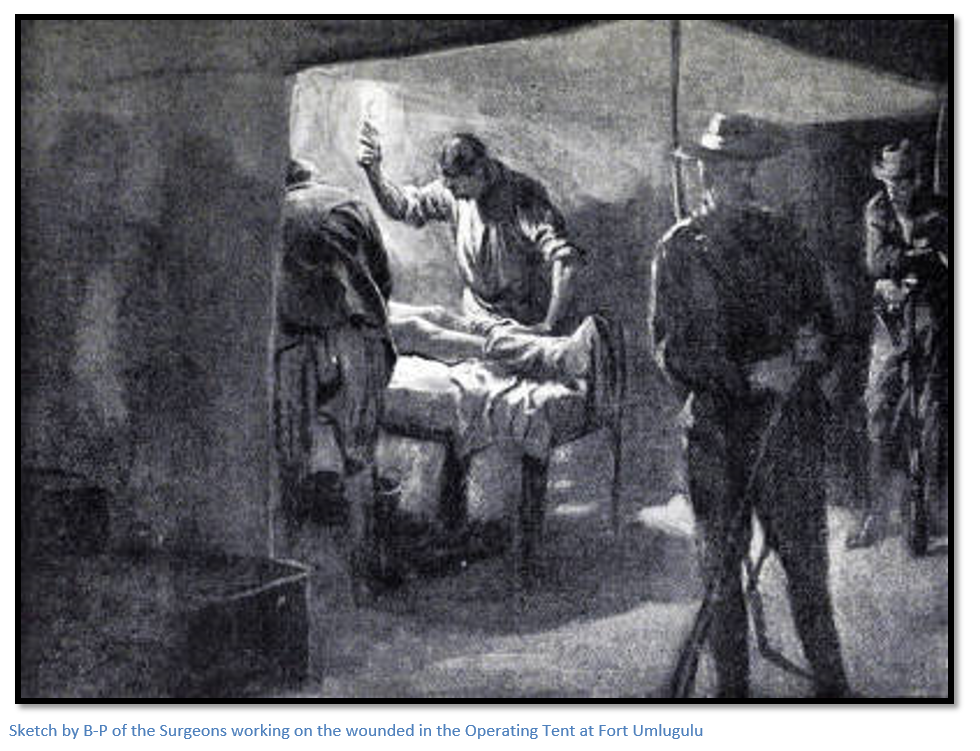

Desultory firing continued until 2pm when the “assembly” bugle call sounded, and all the forces moved back with the wounded on stretchers to the head of the valley where they had assembled that morning. The return march was slow to prevent the wounded being unnecessarily jolted and Fort Umlugulu was reached about 8pm in the dark.

AmaNdebele losses were estimated by B-P and Plumer at around 200 from a force of 3,000; Plumer’s forces lost five killed and thirteen wounded, of which two subsequently died of wounds. Those buried within the cemetery include:

Ainslie, Alexander Battery Sgt-Maj. | MMP |

| KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Gibb, William, Sgt | MRF | C Squadron | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Innes-Kerr Archibald Sgt | MRF | Maxim detachment | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Kershaw, Frederick E. Maj. | MRF | 2nd Batt. Y&L Regt. | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

McCloskie, Oswald D. Sgt-Maj. | MRF | C Squadron, MRF | KIA | 5th August 1896 |

Hervey, Hubert J.A. Lt. | MRF | Dismounted Troop | wounds | 6th August 1896 |

Holmes, Alfred J.E. Tpr. | MRF | D Squadron | wounds | 9th August 1896 |

Wounded include those below and two Cape Volunteers:

Brabant, E, Sgt | MRF | C Squadron | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Currie, William, Sgt | MRF | C Squadron | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Dumeresq, R, Sgt-Major | MRF | D Squadron | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Fowler, C.H, Capt. | MRF | C Squadron | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Fraser, N.W, Lieut. | MRF | York’s West Riding Regt. | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Gordon, T, Tpr | MMP | I Troop | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Howard, H, Lieut. the Hon. | MRF | Cape Volunteers | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Josephs, W, Sgt-Major | MRF | C Squadron | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

McCullock, H.R.F, Lieut. | MRF | Royal Artillery | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Turnbull, R, Cpl. | MRF | Dismounted Troop | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

Windley, Capt. | MRF | Colenbrander's Native Con. | wounded | 5th August 1896 |

As they left the battlefield the MRF was jeered at by Umlugulu’s men who had just arrived after missing the fight; a long-range volley kept them back. The MRF men marched into camp in the dark singing ‘The man who broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’ and were cheered into camp by those who had stayed behind at Fort Umlugulu.

Next morning after the funerals, General Carrington congratulated the force in an address to the men saying the enemy had been defeated, but at the same time expressed regret for the deaths.

Conclusions

Baden-Powell called Tshingengoma battle a victory for Col. Plumer; but his estimation of 200 - 300 AmaNdebele casualties is very probably exaggerated. Carrington’s initial military tactics was to wear the amaNdebele Induna’s down by picking them off one by one through attacking their kopje strongholds. However due to the difficult terrain it was difficult to get to grips with the amaNdebele; the easiest tactic was to fire shells into the kopjes, although this achieved little in military terms. Even moving to an attack position by night march proved ineffectual as the column would be quickly spotted when the sun rose, and the news shouted across from kopje to kopje.

Even Plumer admits most of their encounters were far from satisfactory; “it looked very much as if they had no intention of risking a general engagement but meant to trust to the natural difficulties which their hills presented to save them from any severe loss, and to eventually perhaps exhaust our resources. If they adhered to these tactics we had a long and difficult task before us.”

Epilogue on the main military characters

General Sir Frederick Carrington made his name as a young Captain with the formation and success of mounted infantry, the Frontier Light Horse, in the Ninth Frontier War of 1877 and Basuto Gun War of 1881. By 1888, he commanded the Bechuanaland Protectorate Police (BPP) and was a natural choice for command when the Matabele Rebellion, of First Umvukela broke out in 1896. He delegated most of his responsibilities to Plumer and Baden-Powell and was well-known around Bulawayo at the time for learning to ride a bicycle! He commanded the Rhodesian Field Force during the Boer war and died in his home town of Cheltenham in 1913.

Robert Baden-Powell made many reconnaissance missions into the Matobo Hills and his encounters with John Grootboom and Frederick Russell Burnham, the American Scout, formed the basis for many of his later Boy Scout ideas that took hold here. At 40 years old he became the youngest Colonel in the British Army and achieved fame with his 217-day defence of Mafeking in the Boer War; but his military career effectively ended at the Battle of Elands River in 1900. In later life his military training manual Aids to Scouting became a best seller and he became famous for his founding of the Boy Scout and Girl Guides movement.

Herbert Plumer, who led the Matabeleland Relief Force in 1896 – 1897; was eventually promoted to Field-Marshal and commanded the British 2nd Army between 1915 and 1917, became C-in-C of the British Army of the Rhine, and was appointed High Commissioner for Palestine. He was created a Viscount and died in Knightsbridge in 1932. One of the most successful British Generals; he achieved military success during the Boer War and won a crushing victory over the German Army at the battle of Messines in June 1917 which started with the simultaneous detonation of nineteen huge mines under the German lines.

The Aftermath

In the end, the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela was quelled not by force of arms, although this was tried through the Matabeleland Relief Force, but through negotiation and compromise between the warring parties. [see the article The Matabele Uprising or First Umvukela Indaba site (Rhodes Indaba site) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The military led by Carrington finally concluded that only a war of attrition would beat the amaNdebele, a military tactic which required a ring of forts around the Matobo Hills and destroying their food reserves. The idea of additional Imperial Forces to garrison the forts whose cost would be borne by the British South Africa Company horrified Rhodes and forced him to the view that once again in his career he needed to “square” his opponents and bring the war to an end. He knew from messages received from the amaNdebele that they wanted to start planting their crops and assumed that they would probably lay down their arms and accept peace if the terms were not too harsh and their past grievances were listened to.

So, to expedite the peace process and to save the BSA Company shareholders additional expense, Rhodes decided to initiate negotiations with the amaNdebele Indunas through Johan Colenbrander and Jan Grootboom and Richardson after the capture of Nyambezana, one of Mzilikazi’s wives, which provided the opportunity for opening contact. Both Carrington and the UK Government were initially left on the side-lines of the first Indaba held on 21 August 1896 at a site midway between the site of the battle of Tshingengoma and Fort Umlugulu. [See the First Umvukela Indaba on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Six days later, on 27 August 1897, the second indaba was held 1.6 kilometres from Fort Usher No. 3 at the foot of Usher’s Kop, now called by the local inhabitants Lahlamkonto “The place where the spears were laid down” and this time the military were represented by Colonel Plumer with Lieut Moncrieff and Trooper Laurie.

Acknowledgements

R.S. Baden-Powell. The Matabele Campaign being a Narrative of the Campaign in Suppressing the Native Rising in Matabeleland and Mashonaland 1896. Methuen & Co, London, 1901

F. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Byo. 1972

O. Ransford. Bulawayo: Historic battleground of Rhodesia. A.A. Balkema Cape Town 1968

H.C.O. Plumer. An irregular Corps in Matabeleland. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Ltd, 1897