Home >

Matabeleland South >

Battle of Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele) on the 1 November 1893

Battle of Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele) on the 1 November 1893

National Monument No.:

107 and 109

Why Visit?:

This battle fought on the 1st November 1893 was the decisive battle of the Matabele Campaign. The attack by 6,000 amaNdebele, about 1,000 armed with Martini-Henry rifles, came as a complete surprise to the Salisbury and Victoria Columns under Major P.W. Forbes

The Insukameni, Ihlati, Isezeba, Ingubu, Umbeza and Amaveni Regiments fought bravely, but were no match for the crushing firepower of the BSA Company Column’s Maxim machine guns and estimates vary as to the number of amaNdebele killed. The Maxim gun had been invented by Sir Hiram Maxim in 1883. It has been called "the weapon most associated with British imperial conquest" and played a vital role at the battles of Shangani and Bembesi.

Very accessible, the major positions on the battlefield are easily seen and the plaque on the Memorial records the result of the battle and also the bravery of the amaNdebele.

Open Monday to Sunday.

The battle site is on private land and visitors need to ask permission to enter

How to get here:

At the junction of the Bulawayo to Gweru national highway (A5) and the White’s Run road 34 kilometres from Bulawayo is the Battle of Bembesi Monument on White's Run Farm.

Note: the Monument plaque states the battle was fought 300 yards south; in fact, it is 1.3 kilometres south.

Following the Battle of Shangani River (called Bonko by the amaNdebele) on 25th October, the Columns moved in their parallel tracks west south west towards Gubulawayo and their impending confrontation with Lobengula.

On the morning of 1 November 1893 a thick fog prevented the Columns moving until 8 am but the scouts reported the country was clear ahead. Having passed some kopjes they trekked about 4 miles (6 km) and came to the headwaters of the Ncema river.[i] The scouts returned and said they were unable to get closer to Gubulawayo with the increasing number of amaNdebele forces. However they had questioned two women at a kraal and heard that King Lobengula had left the royal capital and that nothing had been heard of the Southern Column with Goold-Adams and Raaff. As the Columns advanced the scouts and flanking parties saw increasing numbers of amaNdebele, but they kept their distance, before the Column came onto a high ridge and laagered about midday. There was open country on all sides except the north and east where the bush encroached to within 400 yards (366 metres) with Ntabazinduna hill to be seen about 10 miles (16 km) to the north.

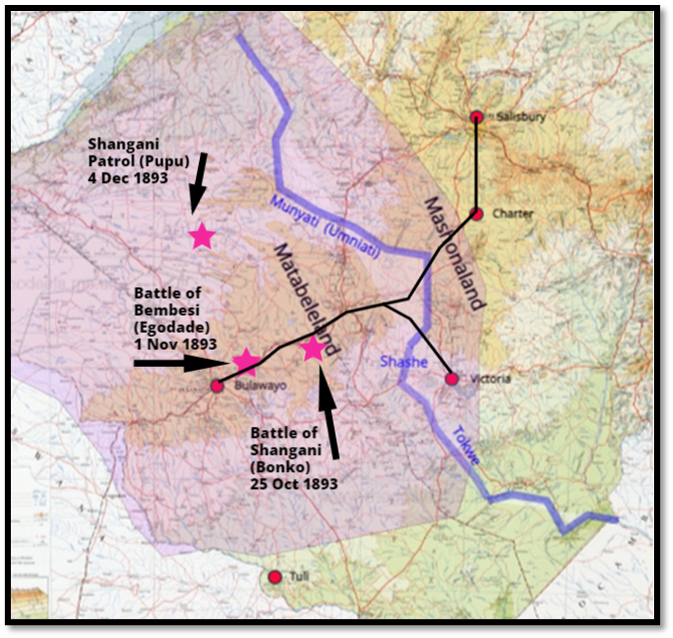

Map used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk Adapted from Stafford Glass – the amaNdebele border or boundary (both terms are used) as understood by Jameson along the Munyati (Umniati) a line south to the Shashe river, then along the Tokwe. Their raiding area after 1891 indicated by the pink coloured area

The Bembesi Battlefield

The ridge was level to the north for about 1,000 yards (914 metres) To the south it sloped quite steeply but with several spurs running out and the nights’ laager was formed on one of the western-facing spurs near an old kraal site. The nearest water was 1,200 yards (1,100 metres) to the south, a tributary of the Ncema river and the Column’s horses and oxen were taken down to it, with orders to return as soon as they had been watered so they would be under the protection of the laager. The morning had been very cold, eighteen oxen had refused to rise at the previous night’s laager and been left behind and three horses had bolted, so some of the native contingent were sent back to see if they could recover them.

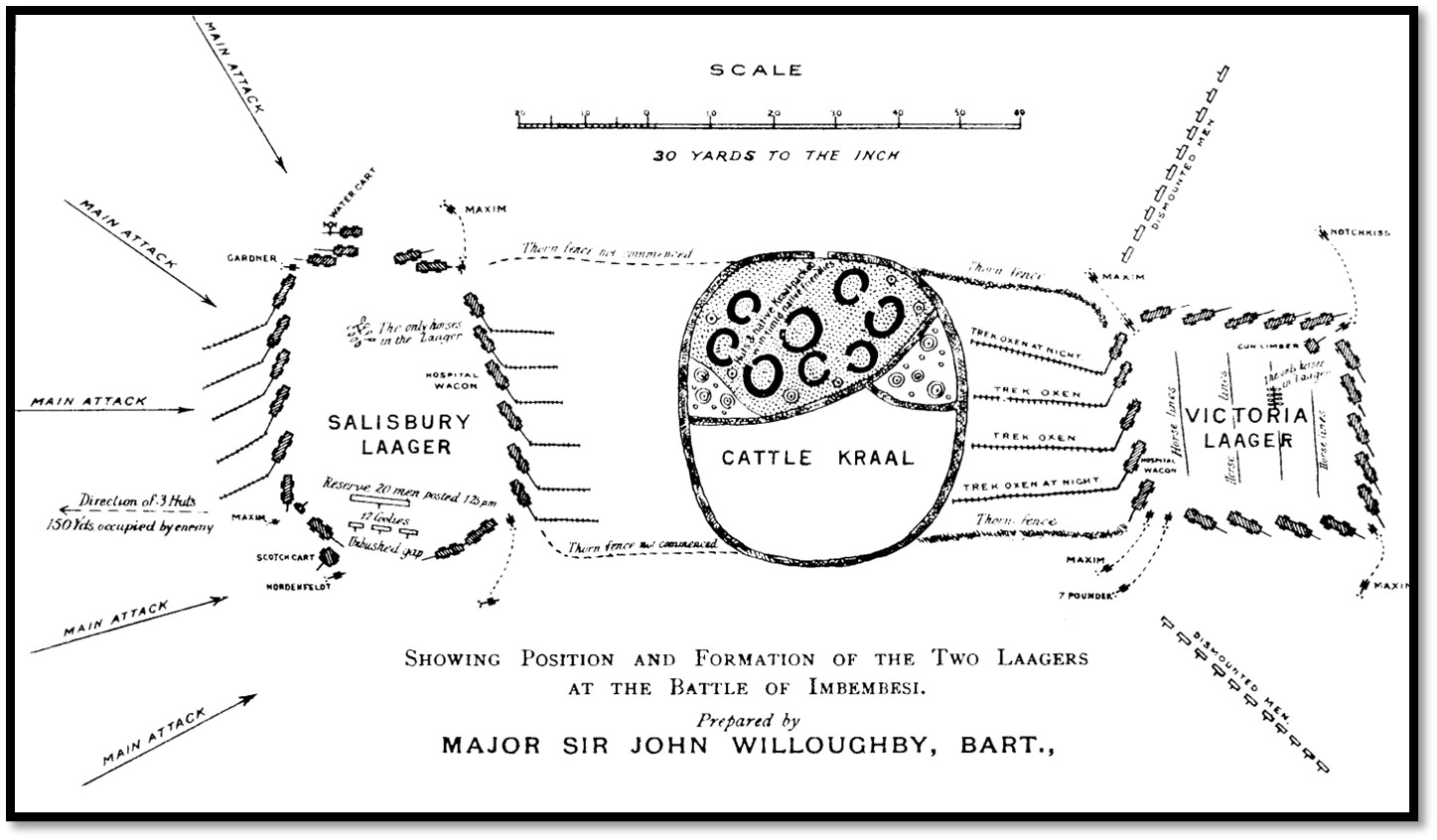

The Salisbury and Victoria Columns, numbering 672 white men with Martini-Henry rifles (about 396 mounted) and an unknown[ii] number of Shona tribesmen on foot, two seven-pounder guns, a one-pounder Hotchkiss, five ‘galloping’ Maxims, a Gardner and a Nordenfelt approached on parallel tracks from the east[iii] and laagered about 11:50 am on the high point of a spur 1.3 kilometres south east of the memorial and a few hundred metres west of the White’s Run Road; the Salisbury Column on the current site of the Terblanche family cemetery and the Victoria Column a little south on the site of an abandoned kraal.

The combined laager area extended about 160 metres, but an abandoned kraal with eight huts separated the two Columns thus restricting their mutual supporting fire, there was also dead ground and thick thorn bush in the north and east which enabled the Umbeza and Ingubu Regiments to approach quite closely to within 500 yards (460 metres) without being detected. Both Columns’ oxen and most horses were taken over a kilometre away where there were pools of water in the Ncema river headstream. The troopers were relaxed and making lunch as it was midday and the thorn scherms (fences) to join the two laagers were still not completed.

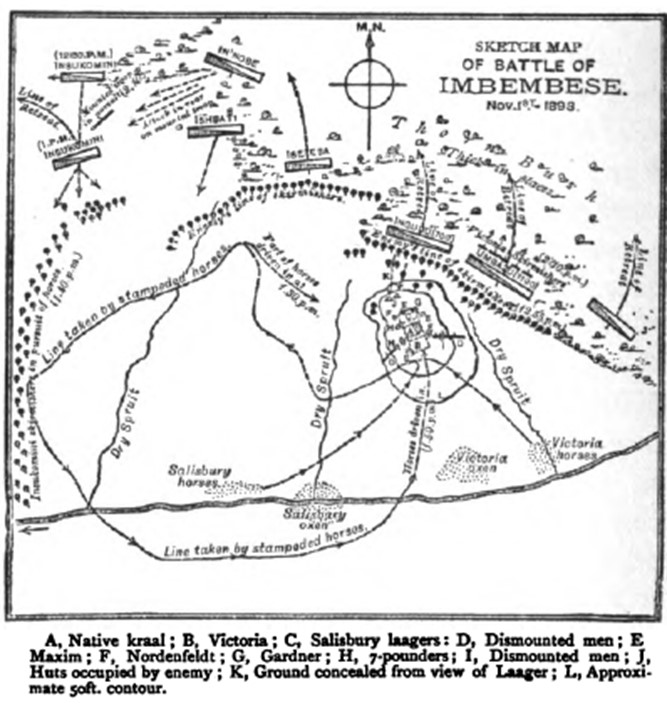

A plan of the Bembesi laagers, Salisbury on the north side, Victoria on the south side by John Willoughby in The Downfall of Lobengula

The first amaNdebele are spotted at midday

As orders were being issued at 12:50 pm, a large number of amaNdebele driving some cattle were seen on the west side of the laager about 1,800 yards (1,645 metres) away. Those at the laager thought they were part of the retreating forces, in fact it was the right horn of the amaNdebele attacking force composed of the Insukameni, Ihlati and Isezeba regiments. The seven-pounder fired several shells at them followed by the Victoria Column’s Maxims and this stopped their forward encircling momentum and alerted the Columns to an amaNdebele presence. The Amaveni regiment, the left horn, was then spotted on the east and also shelled. Moments later the whole edge of the bush on the north side of the laager came alive with amaNdebele ‘the chest of a typical amaNdebele attack’ as the Ingubu and Umbeza Regiments burst out from the bush.

The usual amaNdebele tactic was to attack before dawn; but the amaNdebele Regiments comprising some 5,000 – 6,000 warriors[iv] from the Insukameni, Ihlati, Isezeba (Siseba) and Amaveni Regiments that had fallen back after the fight at Shangani, were now joined by the Royal Regiments, the Ingubu and Umbeza, and made good use of the cover from the thick thorn bush and the centre’s mass attack at midday came as a complete surprise. The 1,400 young warriors of the Umbeza and Ingubu Regiments burst out of cover and charged the nearest laager, that of the Salisbury Column, 400 yards (366 metres) away across open ground, firing their guns on the move, but their shooting, although heavy was inaccurate, and caused few casualties, while the Columns raced to get their Maxim’s into action. The attack on a heavily defended laager was in direct defiance of Lobengula’s orders, which were to attack at river crossings, as happened at Shangani River.

A mounted picket is taken by surprise and overwhelmed

A mounted picket of two men,[v] Troopers White and Thompson, were 600 yards (550 metres) north of the laager, towards the intersection of the A5 and White’s Run roads, was taken completely by surprise[vi] as they sat under the shade of a thorn tree apparently not keeping an active watch. They failed to see the amaNdebele creeping up on them, Frederick Thompson could not catch his horse and climbed a tree, but was killed; White caught his horse, then fell off and ran exhausted into the laager, luckily keeping to the line of the future White’s Run road, so the Gardner gun under Corporal Whittaker could keep firing at the pursuing warriors immediately behind him. The farm was later named White's Run. Forbes clearly blames the pickets for not keeping a proper look out.

For ten minutes the intensity of the amaNdebele firing matched that of the Salisbury laager that was taking the brunt of the attack. The warriors were charging against a Maxim, a Gardner and the Nordenfelt machine guns and 150 M.H. rifles, in the open and in broad daylight. They got within 300 yards (275 metres) and Forbes writes, “held their own there, they could not get any closer and were at last forced to retire.” He says there were three half-built huts about 100 yards (90 metres) to the left front of the laager face and in a slight depression. Five warriors managed to crawl to them under cover and opened an accurate fire on the laager and were difficult to dislodge. Three eventually escaped, one badly wounded, leaving two dead.

Major Alan Wilson, the commander of the Fort Victoria Column wheeled around three of his Maxims, and the Hotchkiss gun to the eastern side of the Salisbury laager which added considerably to the firepower being poured onto the Ingubo and Umbeza Regiments directly attacking the face of the laager. An amaNdebele survivor recalled that when the "sigwagwa", as they called the Maxims, opened fire, "they killed such a lot of us that we were taken by surprise, the wounded and the dead lay in heaps."

Nevertheless, the warriors rallied and returned to the charge at least three times, advancing to within a hundred and ten yards of the laager. Sir John Willoughby, who was with the Column, later said, "I cannot speak too highly of the pluck of the Ngubo and Imbizo Regiments. I believe that no civilised army could have withstood the terrific fire they did for at most half as long." But the only result of their incredible courage and discipline was the loss of some 500 – 600 killed and wounded, before they finally retired.

View from the laager site to the west

The Column’s horses stampede

Disaster was narrowly averted when the Column’s 400 horses were being driven up to the Victoria laager. The herdsmen ran out to meet them and this started a stampede towards the Isezeba Regiment in the west. This would have been a calamity, but as they stampeded up the hollow towards the amaNdebele, Capt. Henry Borrow, Sir John Willoughby and Trooper Neale galloped after them and headed them off within a hundred yards of the amaNdebele, only one horse being killed under the heavy fire.

All attempts by the amaNdebele Regiments to work their way on the left and right flanks were defeated by the long-range fire of the Maxim machine guns. The fighting lasted about forty minutes before the amaNdebele retired, Napier says they retired, “but did so in a sulky sort of way, not hurrying or taking cover, but walking quietly back until they were out of sight.”

Once again, it was the Maxim fire that proved decisive. Sir John Willoughby says, “I think it is doubtful whether the rifle fire brought to bear would have succeeded in repelling the attack; the Matabele themselves have since stated that they did not fear our rifles so much, but that they could not stand against the Maxims.”

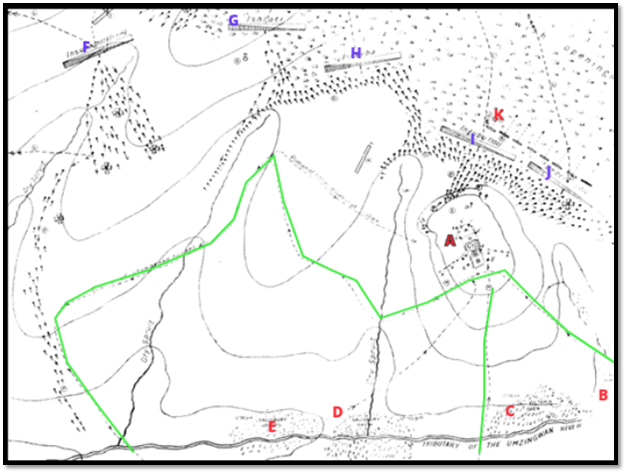

Adapted from Sir John Willoughby’s Plan IV in The Downfall of Lobengula

KEY

A Salisbury and Victoria Columns laager

B Victoria Column horses that bolted along a route shown by the green line

C Victoria oxen

D Salisbury oxen

E Salisbury horses

F Insukameni Regiment

G Ihlati Regiment

H Isezeba (Siseba) Regiment

I Ingubu Regiment

J Umbeza Regiment

K Pickets White and Thompson

View looking east looking up to the laager site on the ridge

After just over an hour the Battle is over

By 2 pm the amaNdebele attack had ceased and the demoralised impis were retreating. However some long- range firing continued, so one hundred Victoria dismounted men under Capt. Delamere and Lt Stier were sent to clear them out of the bush and Capt Borrow with B Troop went to support them and prevent any attempt to cut them off. Capt Bastard was sent to remove any warriors in the valley behind the next ridge line, but he got too near the bush and an attempt was made by the Ingubo Regiment to cut him off, but several shells from the seven-pounder gun and a well-aimed burst from Lt Tyndale-Biscoe’s Maxim at 1,800 yards (1,645 metres) thwarted the attack.

Some of the wounded amaNdebele were brought in to have their wounds attended to. One of them brought in, laughed and said, “Fancy the Imbezu being beaten by a lot of boys!” They told us that when the Insukameni Regiment reported to the King that they had been beaten at Shangani, The Ingubu and Umbeza had laughed at them and told the King that ‘they would not have to fight but would simply walk into the laagers and lead us out on the other side but would kill the older men and keep the rest for slaves.’

Casualties

The European casualties included Trooper Frederick Thompson, who is buried on the battlefield; Troopers Carey [vii] and Siebert who both died of their wounds on the night of 3 November and Trooper Calcraft, who was on the Gardner gun, died three days later at Bulawayo. The wounded included Trooper Barnard shot through the knee, Trooper Crewe the right leg, Capt Moberley, who took Trooper Calcroft’s place on the Gardner gun and Trooper Mack had superficial wounds, Driver Brown was shot in the hand, another in the arm and three horses were killed. The Victoria Column lost a horse.

Forbes states most of the amaNdebele dead were carried away by their fellow warriors after the Battle. He does not give an estimate of the number killed, but he says the Umbeza, who formed ‘the chest’ of the attack, lost 500 dead and wounded from their total strength of 700 warriors.

Ammunition usage

The columns used 8,600 M.H. rounds, 25 seven-pounder shells and 30 one-pound Hotchkiss shells. The amaNdebele used a wide variety of rifles apart from Martini-Henry’s and their ammunition, but also four-bore elephant guns and express rifles. Before the battle the King had issued the Umbeza Regiment 100 M.H. rifles and 10,000 rounds with another 10,000 rounds issued the evening before the attack.

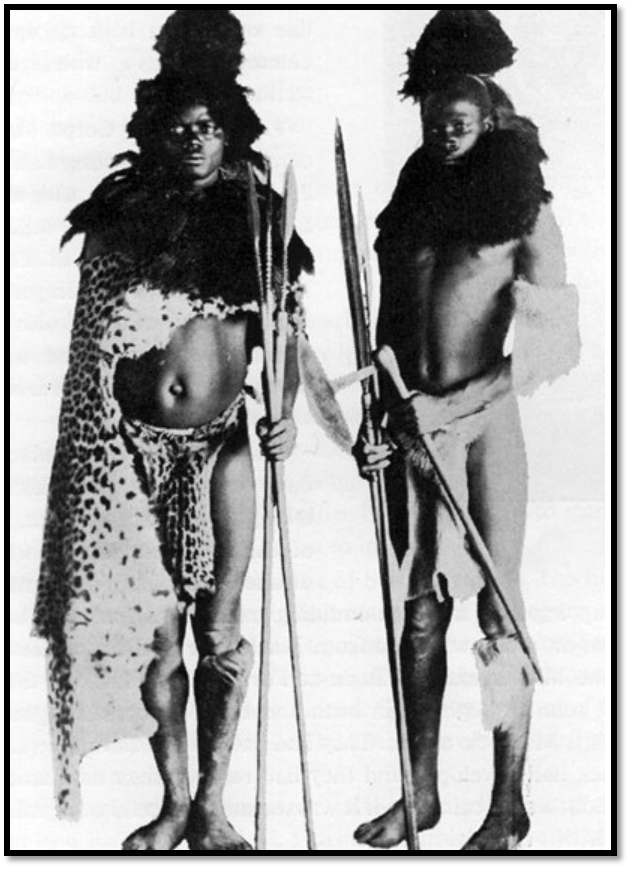

AmaNdebele Amajoda dressed in their finery

Jack Carruthers account of the Bembesi Battle

The following is compiled from the note books of Jack Carruthers, a Victoria Scout present at both the Shangani and Bembezi battles. When we rode into the Bembezi laager on the 1st of November 1893, the cattle and horses had just gone out to feed and water.

The battlefield is situated on the south slope of the open country, east of the railway crossing White’s Run farm, where the new motor road turns off to Filabusi. We had not long to wait when the vedettes started firing and the alarm was given. We saw a riderless horse making for laager and White coming in, running with the Matabele close on his heels, his companion, Thompson, having been stabbed.

The laager having been carefully formed in a secure position, the Matabele had no chance of reaching us. Most of those who were killed lay four hundred yards away on the west side. We almost had a mishap, our horses stampeding as we hurried back into laager and they were only saved by a Dutch chap, Piet Mathuisen by name, racing them down and turning them, heedless of the Matabele who were trying the Zulu stunt of closing us in.

There were about six hundred Matabele killed in this fight and I afterwards found many dead who had found their way back to their kraals and died there of their wounds.

We suffered one killed and eight wounded, two dying later in the day. My friend Tom Lynch was slightly wounded. A few of the Matabele were brought into laager for information, but nothing would persuade them to speak or say anything. The Matabele had retreated quite out of sight. We collected quite a number of Martini-Henry rifles, part of Rhodes' payment to Lobengula.

The next night we laagered up near the present railway crossing on a small river east of Ntabazinduna, where we again set up a few rockets. We were now nearing Bulawayo. [viii]

Frederick Thompson’s grave and Loyal Women’s Guild Pioneer Memorial cross on the Bembesi battlefield

Trooper George Rattray's version

Another account of the Bembesi battle quoted by R.C. Knight is given by George Rattray in a letter written soon after the Battle of Shangani to his mother:

We continued our march straight for Bulawayo capturing cattle as we went, burning every kraal we came near and destroying the grain, the natives having left everything behind. I suppose we have burned about some six thousand huts, one kraal alone having 150 huts in it. The next place we were attacked was at Bembezi about 21 miles from Bulawayo, and by the two crack regiments, the regiments that have never known defeat, the "Imbezi" and the "Ingobo", the King’s own. We had just laagered up at dinner time when they were seen trying to drive off the horses and cattle. The seven pounder stopped that little game and all the horses and cattle were got into laager. They then came on from the other side where there was a bit of bush, coming within 100 yards of the laager, squatting down and coolly firing at us on the wagons, but they were soon silenced, the maxims started then on those in the bush. You could see them mown down just as if with a scythe but they were there by the hundreds and thousands. The seven pounder started firing shrapnel, a shell that bursts in the air pouring down a regular rain of bullets. That silenced them a bit and then our two foot regiments, the redoubtable foot sloggers, were ordered out with fixed bayonets to clear the bush.

This they did in about twenty minutes, the firing on both sides being heavy but strange to say not a man of ours was hit while the Matabele dropped in all directions. The enemy then retired leaving over 1,500 dead. I was not in the laager at the time being posted vidette on a hill about a mile off and had a good view of it all.

I was by a burning Kraal and the smoke hindered one from seeing what was going on my right till a bullet came unpleasantly near my head. I thought it was time to be moving so mounted my horse and rode off. Another bullet landed in front, so I had a look round and there was a Matabele squatting behind a stone coolly practising at me. I couldn't stop as the natives were closing round towards the laager, so galloped off and got in all right. I was lucky as two other videttes posted from the Salisbury column both got assegai’d and shot. From our laager no one was killed or wounded but the Salisbury lost 3 killed and seven wounded. By Jove, but the ground was strewn with Matabeles up in the bush. We took about twenty rifles from the dead, rifles of all kinds, elephant guns or gas pipes, blunderbusses, Martini Henry's and repeating Winchesters which they have got from hunters going into the country.

We heard next day from a Matabele the scouts captured, that 1,700 Imbezi went to the King and asked leave to go and catch the white man and bring them in for the King to play with. The King said, "You can go, but I'll eat a live dog if you beat the ......." and 200 returned to the King. Lo Ben said 'Well, where are the wagons of the white man, I don't hear them.' The remnant said, “They are over there still.” “Well, where is the Imbezi, where is the Ingobo?” “They are finished” answered the 200. I believe Lo Ben was said to say “Well, then, if they are finished, I am too.” So giving the word to his indunas, he packed his wagons and all Bulawayo trekked north, Lo Ben blowing up his house behind him so that when we arrived in Bulawayo the next day his house was in ruins. I can tell you we are living rough now, half rations, double work and now today they tell us all the meal is finished. We have been living mostly on corn, which is beastly unpalatable and indigestible, but we can get as much meat as we want. Fever was pretty brisk about forty miles back and I had a couple of attacks in a week, but the country there was very low and a lot of stagnant water knocking about.

Bulawayo is as healthy a place there can possibly be, but at the same time the dust is such a nuisance, volumes of dust sweeping through camp every minute, getting in the grub that is being cooked, let alone one's eyes. I believe we are being disbanded next month. A hundred BBP and fifty of the Tuli Column arrived yesterday and together with one hundred of our chaps started in pursuit of Lo Ben last night. They are to travel all night and come upon the natives at daybreak. They have taken maxims and two seven pounders as Lo Ben has taken up a very strong position on a Kopje with thick bush round it for miles.

The day after we got up here we rushed up to Lo Ben's house, or rather ruins, to see if we couldn't find some of the talked-of riches but bar a silver elephant and two Jubilee shillings nothing of any value was found, but the collection of things was amusing, but of course everything was destroyed by the explosion. There was beads by the ton, cartridges of all kinds blown to bits, I should think there must have been quite 40 000 rounds destroyed, musical boxes, opera glasses, guns and toys of all descriptions. The house was built of bricks and stood in the centre of a big oblong...around which were about 200 huts belonging to his wives and head indunas. Bulawayo is a big place. There was a sale here of the stuff in the white man's store, a lb bacon fetching 8 and 9 shillings, a pound tobacco 10s and preserved meat and fish 5 and 6 shillings a tin. A small tin of pearl barley went for 26s and compressed vegetables 21s a tin. The chaps made more money that day than they had taken ever since they started trading in Bulawayo.

Raaff’s column with 50 wagons is expected in today together with the remainder of the BBP. Two companies of the Black Watch, two companies of Dragoons and a company of the CMR are ten days behind and will bring full rations for us all. We have heavy work now building a fort, three hours fatigue a day, let alone guards and videttes. No gold has been found in the country yet, so farms are fetching low prices at present, £100 being the highest price paid for a right up to now, very few are off as everyone knows the country is bound to go ahead.

I am expecting a big bundle of letters from Victoria when the carrier comes as I have not heard from you for a couple of months. I must now end up hoping you are all very well and with best love to all I remain,

Your affectionate son,

George Rattray" [ix]

The Bembesi laager site in 2015

Frederick Burnham’s version of the Battle

These abbreviated notes are from Burnham: King of Scouts, although the account, like the book, owes more to the author’s imagination than a true account and should be treated as very much exaggerated, At 1 o’clock, with the sun shining through cotton-ball clouds, Major Forbes ordered mess call. The troopers were forming in line to eat when the bugler sounded the alarm of an enemy attack. The Cape boys abandoned their scherm-building and sought shelter inside the two laagers. From the onset, this battle was a real corpse-and-cartridge occasion. The air was hot and thick with bullets. Fred heard the blowing of bugles and shouts of officers yelling orders. White soldiers dashed about, searching for their weapons and running toward battle stations. Burnham took up his post at the rear wheel of a trek wagon. He saw a blaze of flame issue from the Regiment’s rifles. His view of the enemy was blocked by the Salisbury Column laagered to the north. Major Allan Wilson rode up on his bigger version of Zebra. “I want volunteers.”

A trek wagon was pulled out of line to make an opening for Wilson’s volunteers. Fred laid down the Martini-Henry issue rifle and picked up his Winchester carbine. Mounting Zebra, he rode out to catch up with Major Wilson. “Forbes won’t get all the credit this time,” Wilson yelled over the din of battle. Burnham could scarcely believe what he was hearing. Sweating profusely, the commander of the Victoria Column galloped north, leading a small group of men into the thick of the action two hundred yards away. Fred was pondering Wilson’s jealousy when he heard a commotion behind him. He looked over his shoulder and his heart skipped a beat. Horses and oxen from the Victoria laager were escaping from the unfinished cattle scherm. If the Matabele were to perfect a stampede – as the Apache’s surely would – the whites would be unhorsed in the heart of Matabeleland. For that mistake, the penalty is death. I’ll never see Blanche or Rod, or the unborn baby. I hope the end will be swift.

Fred spurred zebra to warn Major Wilson. As he drew alongside, the rattle of Maxim fire drowned out his voice. Ahead, he saw a large induna leading an assault. Suddenly, the hairs on Fred’s neck stood out. Running behind their leader, wearing war paint and carrying shields, were more Matabele soldiers than he had ever seen. They were formed into an unwavering line in the deep veld grass, their horn-crescent formation spread over the open meadow for nearly a mile. The blacks screamed “jee” and ran towards the Salisbury laager.

Their charge was answered by a peppering of rifle fire, followed by the heavier, staccato burst of the Maxim guns. Hundreds of blacks fell. Still the horned crescent rolled across the veld like an ocean wave. Seemingly nothing could block it. “My God” Wilson cried out. “Thousands of them.”

“Major” – Fred tried to warn his commander about the escaping horses, but an explosion from the Salisbury laager cut him off. It was the Hotchkiss. A moment later, a shrapnel charge from Charlie Lendy’s cannon exploded over the left flank of the horned crescent. A score of Matabele fell, dead or wounded. More Hotchkiss shells exploded. The acrid smell of cordite mingled with the reek of horse manure. The young blacks on the left flank of the horned crescent crumbled, broke ranks and retreated toward the Bembesi River.

The centre of the impi, the older, more experienced warriors, continued a stern assault. A shrapnel charge from the Hotchkiss exploded over the right flank, dismembering a dozen attackers. Like the grape-shot cannons of the American Civil War, each shot from the Hotchkiss gun cleared a swath twenty yards wide of all humanity. Survivors fled to the trees to fashion nooses and hang themselves. Fred could scarcely believe his eyes.

That’s when Captain Lendy turned his attention to the centre of the horned crescent, the symbolic head of the Cape buffalo. In quick succession, the Hotchkiss barked three times. Shrapnel charges exploded over the centre of the black impi, and the Regiment began coming apart. Panic stricken, the elder warriors ran in circles while others tried to fire at the incoming artillery shells. Then the Maxim’s found the range and swept the Matabele down like blades of grass before a farmer’s sickle. The sun augured mercilessly on this scene of dismemberment and destruction. Unnatural noise filled the air, a sonic horror. Hyenas and vultures awaited joyfully. As dying men evacuated their bladders and bowels, the combined stench of human piss, shit and death was overwhelming.

Three times more the Matabele regrouped to launch attacks and thrice more the Hotchkiss broke up the horns of the crescent and then the head. Finally, the Maxims opened up to mow down the survivors. It was the worst military defeat that Burnham could conceive of and he was sickened at the frightful squander of human life. Then he recalled the escaping horses. Burnham looked back at the Victoria Column, blood racing. Two men were chasing the fleeing stock. One was Captain Henry Borrow, the adjutant of the old Pioneer Column, the group that had opened up Mashonaland in 1890. Borrow was well mounted and doing a splendid job. It was the other rider who astonished Fred. Digby Willoughby was astride a bay horse and riding as if they were pursued by lions. With pistols in each hand, he drove back a score of running Matabele who tried to capture the galloping horses. He then manoeuvred the animals toward the Bembesi River, a resourceful act because after a good gallop thirsty horses will always stop to drink. Fred relaxed knowing the stampede was ended.

If the Matabele commander planned a fifth assault that day, it never came. The firing died away and in time the troopers rode out to survey the battlefield. Within half an hour, the area had returned so much to normal that a herd of zebra began crossing the Bembesi River. The number of dead was enormous. At least eight hundred bodies lay in the field, some warriors blown apart by artillery and machine gun fire. The wounded appeared to number equally high. The ultimate count was that fifteen hundred blacks died as a result of the forty-five-minute engagement. The officers called roll to assess casualties; four men killed and seven wounded.[x]

John Meikle’s account

Although Meikle was not at the battle itself, after the occupation of Matabeleland he was given the task of herding loot cattle back to Victoria and part of his story contradicts Major Forbes’ statement that most of the amaNdebele dead were carried away by their fellow warriors after the Battle. Last night I camped on the site of the Bembesi battlefield where our fellows had kept back the hordes of attacking Matabele. There all around me, more particularly on the north side, were the bones of the Matabele scattered over the veld, lying white where they had fallen.[xi]

APPENDIX B: MAJOR SIR JOHN WILLOUGHBY’S ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF IMBEMBIZI, FOUGHT NEAR THE HEADWATERS OF THE BEMBESI RIVER 1 November 1893 REPORT TO THE WAR OFFICE[xii]

Bulawayo, Nov. 9, 1893

On the 30th of October the two columns trekked to one of the streams forming the head waters of the Manyani river, a tributary of the Umzingwane, here distant about four miles from the Umsingweni kraal of which Sema Pulami is chief. Here it was decided to halt until the following afternoon to give the horses and oxen a much needed rest, the grazing, which for the last three or four days had been very scanty, being here very good. The delay was also necessary to enable us to reconnoitre the country ahead, since the skirmish of the 27th, we had lost touch of the enemy, and were ignorant as to his whereabouts.

On the 31st of October a considerable number of shots were heard at 1 pm in the direction of Umsingweni: this proved to be an attack on Capt. White's scouts by large numbers of Matabele, who had taken up a strong position on a single line of kopjes, at the back of which lay the Umsingweni kraal. Two mounted troops were therefore sent to reconnoitre and on nearing the kopjes we could see small bodies of the enemy moving about on the sky-line, but on approaching to within 800 yards a heavy but ineffective fire was opened on us along the whole line of kopjes, extending for a mile in length. The troops, after returning the enemy's fire for a short time, retreated slowly, and the enemy thereby encouraged, showed in great force, masses of men running down to the base of the kopjes, while large bodies were seen to be rapidly advancing on our right flank over ground much intersected by dongas and sloping away at right angles to the kopjes. However, with the exception of a few who pushed on through a strip of bush to a deep watercourse, running parallel to, and about three-quarters of a mile from the kopjes, the majority did not advance further than their base. The laagers were broken up at 3.30 pm and reformed 1½ miles distant from the kopjes, in a fair position, though at some distance from water. While trekking to this place the enemy showed a disposition to attack, large numbers advancing at a run in skirmishing order on our right flank, but a few well directed shells from one of the 7-pounders drove them back again to the shelter of the kopjes. It was afterwards ascertained from natives that these shells did considerable execution. Contrary to expectation, a quiet night was passed, notwithstanding that it was evident the Matabele had received reinforcements, from the fact of their astonishment at the shells, many of them rushing forward to shoot at them as they burst. The following morning the column moved on and on reaching the Umsingweni kraal we found the enemy had evacuated his position of the previous day after having burnt many of the huts. I estimated the enemy's forces shown on the previous day at 3,000 but judging by the scherm fires and remains of oxen slaughtered behind the range of kopjes, the forces must have amounted to at least 4,000 to 5,000 men.

The country to the west of the Umsingweni kraal, through which it had at first been our intention to pass is bushy in places and broken by watercourses running into the Imbembesi river, the latter some four miles beyond the range of kopjes; had we continued on this course it is almost certain that we should have been attacked while crossing the Imbembesi river in an awkward place, the banks being steep . It was luckily decided, on information received from the scouts, to make a detour south and proceed along the higher ground where the bush was more open and so pass round the head of the river. Several small scouting parties of the Matabele were sighted as we wound our way along for three miles, taking the most open parts - a pretty clear indication that the enemy was close at hand in force and I fully expected an attack at any moment: the general opinion, however, seemed to be that they would not fight.

The open ground was reached at 11.30 am and the laagers formed at 11.50 am on a steep rise 500 yards from the edge of the bush, with a small native kraal in between the laagers, which it was intended to utilise for holding the captured cattle for the night. This position was far from being a good one, for 150 yards away to the right of the Salisbury laager a sudden drop in the ground on the side nearest the bush would enable the enemy to mass in large numbers under cover over an area of about 300 yards square, within 50 yards of the bush and 150 of the laager. The water too, was about one mile distant to the south in the open. The Victoria laager was well formed and partly bushed with thorns that had been carried on from the last camp by the Mashona contingent; the Salisbury laager was not so well made, in shape more or less of an oval, open at both ends in front and rear, with wide gaps where the guns stood and also between some of the wagons. Up to the time of the attack it had not been strengthened, the natives being still out cutting bush for that purpose. Three roofless huts too, were still left standing 150 yards distant from the right face; vedettes on the north side were placed west of the bush and in it, as well as on the higher ridges of ground east on south and west and east sides.

At 12.50 pm a dense mass of natives were seen emerging from the bush on a high ridge to the north west, about 1½ miles distant, apparently retreating on Thabas InDuna, in the direction of Bulawayo . One of the 7-pounders was run out and a few shells fired in their direction . This movement would appear to have been intended as a feint on their part, for almost immediately afterwards the whole body wheeled to its left and opening out into skirmishing order, commenced advancing rapidly in the direction of the laagers. At this moment, 12.55 pm one of the pickets stationed near the west side galloped in to report that the enemy were coming on rapidly through the bush in great numbers scarcely half a mile away. Within less than three minutes of this report we perceived the enemy ourselves rushing through the bush in splendid order and almost instantaneously occupying its outer fringe in various distances from the Salisbury laager at from 600 to 700 yards to 350 at the nearest point, whence they poured in a very heavy and ever-increasing rifle fire ( chiefly Martinis) as continuous reinforcements kept coming up from their rear.

Our men were outside the laager cooking their mid-day meal and had barely time to snatch up their saddles, rifles and bandoliers to reach and man the wagons. It was not till then that the recall was sounded for the horses and oxen, the furthest away of which were grazing over a mile away, though luckily on the least threatened flank, away in the open. The attack was pushed forward with great determination and admirable pluck for about 20 minutes, being solely directed against the right face and right front and rear of the Salisbury laager, reinforcements working their way up beautifully making use of the cover of every available bush; but in no one place did more than one or two collect together, and pouring into the laager a very heavy though, generally speaking, ill-directed fire - the majority of the bullets passing over our heads - though the wagons and head cover, formed of hastily piled-up kits and meal bags, were struck in many places - a small party of the enemy advanced under cover of the low ground already mentioned and occupied the three huts distant 150 yards and some of our casualties were occasioned through this occupation. Our rifle fire in this direction was not at first very effective, it being difficult from the nature of the ground to ascertain distances; the machine guns, however, did great execution, more especially the Gardner and two Maxims.

In the meantime Major Wilson, seeing that his own laager was not seriously threatened, very judiciously moved out three Maxims and the Hotchkiss gun and also flanked the slopes of the hills on both sides to assist in repelling the attack, yet, notwithstanding the heavy fire of three Maxims, one Gardner, one Nordenfeldt and two shell guns, besides some 400 rifles, the enemy continued reinforcing his first line (though latterly to a lesser extent) up to 1.25 pm when he contented himself with holding for some little time longer the fringe of bush occupied.

The really serious part of the attack was carried out by the Imbeza and Ingubo regiments, 1,000 and 700 strong respectively, backed up by members from these towns, covering a front of about three-quarters of a mile. Near to them, to the immediate right of the Ingubo, the Isiziba pushed on as near as they could without leaving the cover of the bush, distant in their direction about 700 yards. The Ishlati regiment beyond the latter, and in the open, kept at a distance of 1,000 to 1,200 yards, while the Insukameni regiment kept fully a mile away on the extreme right of the enemy's line; the Inxnobo, in the bush to the left rear, never really engaged until they went in pursuit of the mounted troop . Besides the above-named regiments the Inxchlecho regiment and most of the towns that took part in the Shangani attack , with the exception of the Amaveni , were present , but remained in the background in the bush . At 1.30 p.m. the enemy began to show signs of having had enough of the murderous fire he had so long withstood , and by degrees withdrew into the bush , and by 1.50 pm all had sought cover, merely keeping up a dropping fire here and there , and by 2 pm his fire ceased altogether.

At 2 pm 100 of the Victoria men under Capt. Delamere were sent out to skirmish through the bush to our right rear in pursuit of the now thoroughly demoralised Imbeza regiment, and admirably handled by their commander, these men worked exceedingly well and in excellent order, driving the enemy before them for some distance. Some of this party brought in the body of one of the vedettes who had been stationed in the bush and surprised and assegai’d by the Matabele as they first came on, his fellow vedette escaping with some difficulty to the laager, being thrown from his horse when 500 yards distant from it and having to run for his life, being hotly pursued by many of the Matabele. Great credit was here due to Sergeant Whittaker , who with the Gardner gun picked off many of his most pressing pursuers to the right and left of him and thus materially assisted in his escape.

A mounted troop under Capt. Bastard was sent out at the same time as the Victoria skirmishers in pursuit of the Insukameni and Ishlati, who were now flying in all directions across the open towards Bulawayo, but here some 500 or 600 of the Inxnobo regiment, not previously engaged , rushed out from the bush to cut off his retreat, thus placing the troop between two fires. Capt. Bastard's horse being shot in two places and being unsupported, he had to make a hasty retreat under cover of a 7-pounder and Maxim, which being brought to bear at a range of 1,800 yards, made excellent practice and drove the enemy back into the bush with considerable loss.

The horses and oxen as previously mentioned were over a mile distant from the laagers at the commencement of the attack, and the former only reached the laagers 25 minutes later. Just as those of the Salisbury laager were reaching it they were stampeded, either by the heavy fire or by some of the native contingent running out to help to bring them in and they, in their flight, carried with them the Victoria horses; thus between 400 and 500 horses galloped away across the spruit, running 400 yards west of the position and then headed straight for the enemy's lines. Fortunately the enemy opened fire upon them and so turned them towards the open country. Had he not done this all would have been lost to us, the only horses in laager at the time being some half a dozen of each inlying picket and one or two odd ones. Capt. Borrow and myself, followed by a few others, started on these in pursuit, whilst two of the grazing guard stuck with the horses throughout, pluckily endeavouring to turn them, even while heading straight for the enemy and we eventually succeeded in recovering the lot, with the exception of two shot, but the horses were only driven into the laager when the fight was practically over. The Isiziba and Ishlati regiments fired on us while thus engaged, but except two horses killed, without effect, although the nearest range was only some 300 to 400 yards distant. The Insukameni also made a poor attempt to intercept the horses at the furthest point reached by them , but probably deterred by shell and Maxim fire from the Victoria laager, covering us as we were turning, they made too wide a circuit to cut them off in time. The oxen of both laagers remained outside throughout the whole fight, those furthest away only being driven in just at the end.

Our casualties, considering the very heavy and concentrated fire of the enemy, were very small and comprised, Salisbury column: Europeans, one killed, eight wounded (three of the latter died subsequently of their wounds) three horses killed; Victoria column: no casualties except one horse wounded. No casualties among the native contingent, who took no part in the fight, but huddled themselves together in the little native kraal, crowding into every available hut and lying low. From the position of the laagers most of the enemy's fire, being high, must have passed over both. The losses of the enemy must have been very heavy indeed, though difficult to estimate, for he carried off his dead as fast as they fell during the first part of the fight. From personal examination of the ground after the engagement and from the reports of both wounded prisoners at the time and from natives subsequently encountered, they must have amounted to at least 800 to 1,000 killed and wounded and it would appear that the Imbeza and Ingubo were practically annihilated. I must record the pluck of these two regiments, which was simply splendid and I doubt whether any European troops would have stood for such a long time as they did the terrific and well-directed fire brought to bear upon them. It was perhaps fortunate that only a few perceived and made use of the cover afforded by the lie of the ground to our right front, for they might have massed in large numbers there in somewhat dangerous proximity to the laagers; as it was, with the exception of the few mentioned, none were able to approach nearer than within 350 yards. It was also, perhaps, fortunate that these two regiments arrived too late to attack us on the march, whilst winding through three miles of more or less bush country, for had they come on there with the same dash they afterwards showed in their attack, they would without doubt have made it very hot for us.

The Maxims especially and all the machine guns played a most important part throughout and without their assistance I think it is doubtful whether the rifle fire brought to bear could have succeeded in repelling the rush. The Matabele have since stated that they did not fear our rifle so much, but they could not stand against the Maxims. The officers and men all behaved very well and we have now met and beaten severely the three best regiments of the enemy, the Imbezu, the Ingubo and the Insukameni and it has been clearly shown that they have no chance of success in an attack on our laagers, at least in the daytime, as on no previous occasion had the threatened laager been so weakly formed, open at both ends, and with several wide gaps between the waggons and where the guns stood.

Signed J.C. Willoughby

P.S. The exact numbers of the enemy present at Bembesi are not known for certain, but it is generally estimated that they must have amounted to between 7,000 and 8,000 men.

The Battle of Bembezi Monument

A bronze plaque states: “On a hillock 300 yards south of this pillar the Salisbury and Victoria Columns (British South Africa Company’s forces) formed laager about midday on 1st November 1893. During the halt they were heavily attacked by a large force of amaNdebele (Imbizo, Ingubo, Isiziba and Ihlati Regiments with Avavene, Icobo and Insukamini Regiments in reserve) The battle was hard and the amaNdebele charged with the greatest courage three times in the face of machine gun fire, but after suffering very many casualties were compelled to withdraw. This was the decisive battle for Rhodesia and the Columns marched on to Bulawayo which they occupied on the 4th November 1893.”

The Bembesi Memorial with the plaques in English and Ndebele

Frederick Thompson’s grave on the left, the middle four graves have lost their headstones, the Terblanche family on the right. The site 50 yards east of the Salisbury Column laager.

References

P.W. Forbes (Chap VIII) and Sir John Willoughby (Chapter XIII) in W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia. 1971

Notes from Sergeant Jack Carruthers. Victoria Scout Shangani and M ‘Bembezi Fights. October - November 1893. Copyright © 2007 by Ian Carruthers.

S. Glass. The Downfall of Lobengula. Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, London 1968

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. Bulawayo, 1953

R.C. Knight. Letter from George Rattray. The Journal of the Rhodesian Study Circle. 1987

R.L. Moffat. A further note on the Battle of Shangani. Rhodesiana No.18 of July 1968.

C.L. Norris Newman. Matabeleland and how we got it. Fisher Unwin, London, 1895

R.F.H. Summers and C.W.D. Pagden. Notes on the Battlefields at Shangani and Bembesi. Rhodesiana No.17 Dec 1967

Maj. I.M. Tomes. The Matabele War 1893. Heritage of Zimbabwe. No. 17 1998. P18-73

P. Van Wyk. Burnham, King of Scouts. Trafford publishing. 2003

Notes

[i] Sir John Willoughby’s map states the headwaters of the Umzingwane river. In fact they are the headwaters of the Ncema river that is a tributary of the Umzingwane river

[ii] The number of Shona at the Battle of Shangani had numbered over 1,000 but many scared by the fighting had deserted the Column as it came closer to Gubulawayo

[iii] R.F.H. Summers and C.W.D. Pagden. Notes on the Battlefields at Shangani and Bembesi. Rhodesiana No.17 Dec 1967

[iv] Stafford Glass suggests 7 – 8,000 Amandebele warriors

[v] The third picket had gone to get his lunch at the laager

[vi] W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia. 1971. Account by Major P.W. Forbes.

[vii] Trooper William Arthur Cary. Capt Heany wrote, “he was a general favourite an adept at all field sports and a clever lad all round and sincerely regretted by his comrades. He was especially anxious, being a wonderfully good shot, to make good shooting at Imbembesi and it was in eagerly exposing himself with that object that he was hit in the head with a Martini bullet.”

When to visit:

Anytime

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: