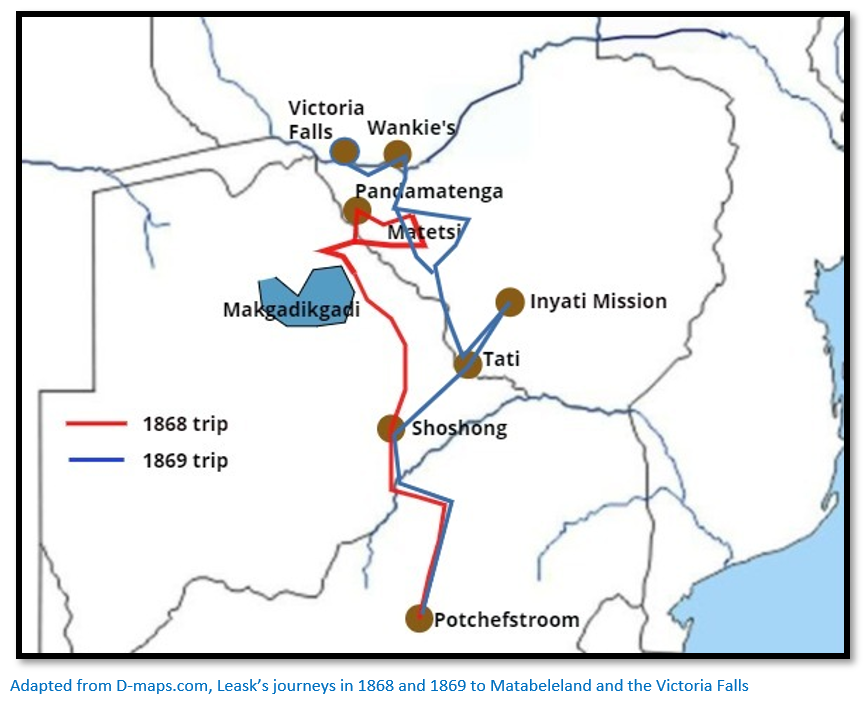

Thomas Leask’s two journeys to the Zambezi in 1868 and 1869

Background

For biographical details see the article Thomas Leask’s Life and Diaries describing Matabeleland and Mashonaland in the 1860’s under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

For other articles on Thomas Leask on the website see:

- Thomas Leask (1838-1912) and his first two hunting trips into Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1866 and 1867,

- Thomas Leask’s journey to Hartley Hills in 1870 under Mashonaland West.

Leask’s journey to the Zambezi from 29 April to 14 July 1868; “My Third Hunt”[i]

This account is written in a day-book that begins in pencil and continues in ink, but there is a gap between 28 June to 13 July 1868 brought about by his malaria fever.

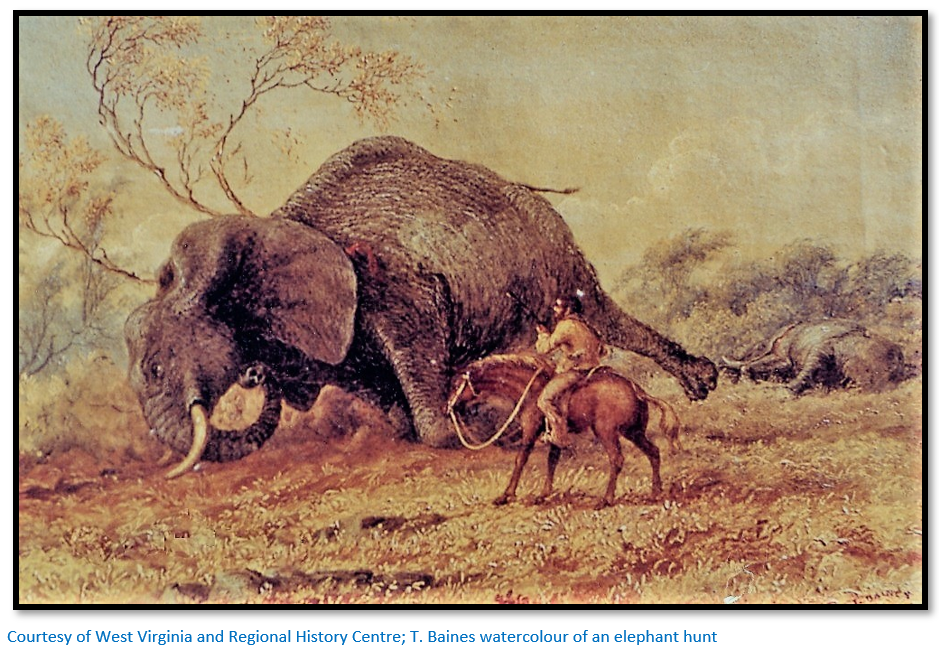

29 April – Leask and William Horn, each with a wagon leave Shoshong on the road to the Makarikari salt pans with a group of local hunters who have six wagons between them. One of the contracts he wrote with these native hunters reads: “Agreement with Piet and Janjie. For each bull-elephant which they may shoot having tusks each weighing twenty pounds and upwards, they receive £3. For each cow-elephant tusk each weighing eight pounds and upwards they receive £1 10s. Thomas Leask.” Janjie is to be paid £1 a month, and of his native servants, Mavuma was to receive a cow as wages for the trip, three others a gun apiece and another, Indoda Umdala, beads.

5 May – “Inspanned shortly after mid-day. An hour’s trek brought us to heavy sand through which we toiled til nearly sundown when we outspanned for an hour. The sand is very heavy.”

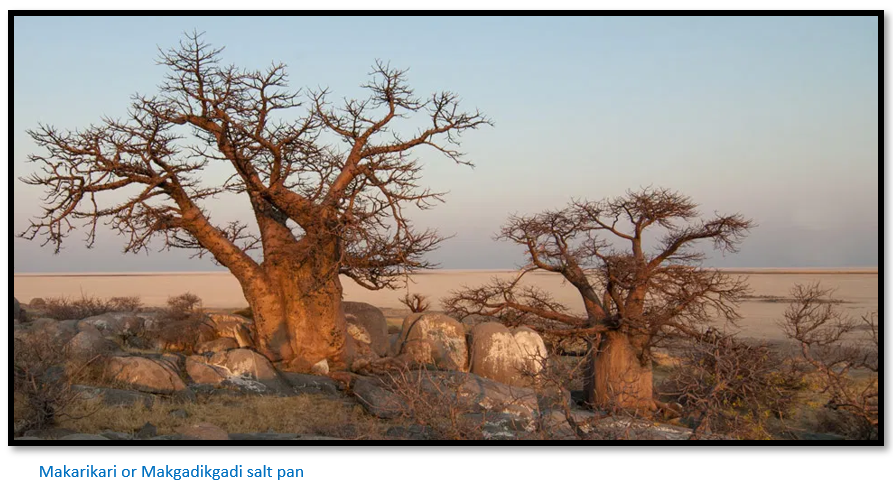

14 May – “…Since yesterday afternoon we have been travelling along the east margin of the great salt pan,[ii] sometimes skirting its edge, then crossing a bay and then through the scrubby bush of some jutting promontory, now and again coming upon a solitary giant of the forest (the cream of tartar tree)[iii] standing like some great beacon or deserted lighthouse. This morning the pan looked like a frozen sea; as far as the eye can reach westward is one level white plain, painful for the eyes to look upon, with here a bush-covered island and there what in the distance seems a bold headland extending several miles into the sea.”

18 May – “Some Bushmen[iv] who came to the wagons yesterday say there are elephants not far from here to the eastward, in consequence of which report several of the hunters started in search of them this morning. The wagons started about an hour after sunrise. An hour’s trek brought us again to the salt pan, part of which we crossed and outspanned at Shua,[v] where the river Nata joins the pan…When we inspanned this afternoon we turned away from the salt pan and trekked up along the Nata.”

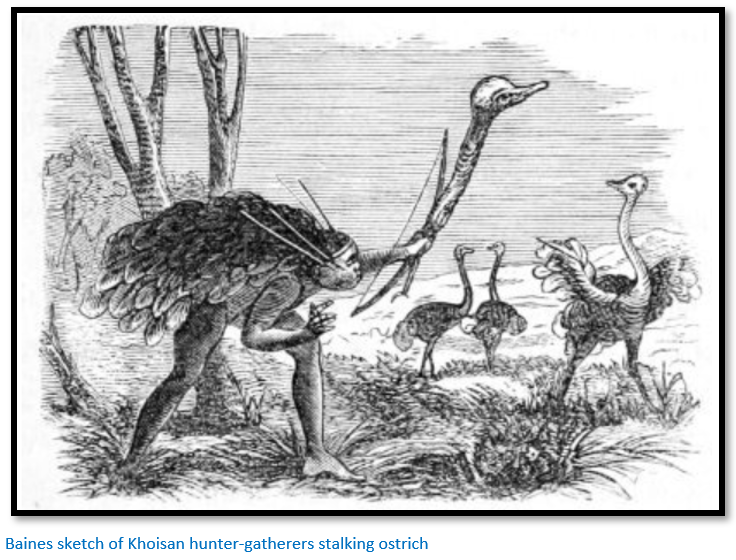

Leask killed his first ostrich which he says was a great fluke as the bullet struck the ground before ricocheting up and knocking down a fine male ostrich. “Though I don’t profess to be a hunter and am willing to admit that I am a very poor marksman, still I have killed some of every sort of game that I have seen with the exception of lion…”

19 May – Piet the wagon driver shot a lion and some others shot two rhinoceros near the wagons.

21 May – “By sunrise we were trekking again. The poor oxen looked very hungry and seemed tired. In some places the sand was uncommonly heavy and the thorn-bush so thick that the driver could not walk alongside of the oxen in which case our progress was slow…” They reach Mantlanyane, 113 kms (70 miles) south west of where the Nata river intersects the Westbeech road (i.e. on the present Zimbabwe – Botswana border) “This is part of the country much frequented by elephants and though it has been hunted for many years elephants are always to be found in it…An old Hottentot told me today that he once hunted here with Baldwin.[vi] One day they found elephants quite close to this water and the thorn-bush was so thick that they left the greater part of their clothes on the hooks of the wait-a-bits [Afrikaans: wag-'n-bietjie] and returned to the wagons naked, torn and bleeding.”

22 May – the native hunters shot an elephant the day before and five on this day. “There was a dispute among the hunters, the cause of which I did not inquire, but they made noise enough.”

27 May – meet Van der Berg at Tamasetsi pan and combine parties. “We are now eleven wagons together.”

1 June – “…We came across elephant spoor today, there seemed to be a large troop of them. Everyone that had a horse and many that had not, went in search of the elephants. We were trekking along very slowly through some heavy sand when an elephant crossed a few hundred yards in front of the wagons. Every man seized his gun but my boy Janjie was too sharp for us, so he gave it the first shot, which brought the elephant to a standstill and a second shot by Van der Berg dropped him; he fell close by the wagon road.” Subsequently one of Sechele’s hunters claimed that neither Janjie nor Van der Berg fired at the elephant at all, but he was laughed at by the other hunters.

4 June – “inspanned at sunrise and got to Deka where we found Van der Berg. Here is a fine stream of water; it is quite a delight to see such a thing again and the luxury of a drink of clear crystal water, after being compelled to drink a decoction of mud, urine and water – this with the luxury of a pleasant bathe, is grand. Give the drunkard his spirits, the tippler his beers and ales, but give the African traveller a stream of clear, pure water.”

8 June – camping on the Matetsi river headwaters. “The Bushmen[vii] returned yesterday and reported the country to be dry. Consequently we inspanned this morning and trekked on the Fall road[viii] as far as Pandamatinka [Pandamatenga] where we arrived shortly before sundown. The road goes about a day further [towards the Victoria Falls] but we have decided to halt here because some hunters got their oxen stuck[ix] by ‘fly’ last year at the old stand-place ahead.”

15 June – Leask falls sick and his diary entries are sparse

29 June – Van der Berg having being unsuccessful in finding Mababe Flat leaves for Wankie’s town. Leask has been sick with fever for some weeks having already sent Piet and Mavuma to trade at Wankie’s.[x] On his return Mavuma faithfully nurses Leask and Horn and Van der Berg[xi] do what they can. “But for the careful nursing of my good old boy Mavuma I should never have lived to leave the place…After some three days Mavuma pressed me to take some gruel. I told him it was useless as I was going to die, in fact was dying. He replied: suppose you are dying; you may as well die with something in your stomach! He looked at me so earnestly, and ill as I was, his remark amused me and to please him I said: Alright make me some gruel. I shall never forget how that dear old face brightened then. I swallowed all the gruel and not long after, like Oliver Twist, asked for more.”

Leask sends a present[xii] to Sipopa Lutangu, King of the Lozi people, who inhabit Barotseland with a request to trade in Barotseland but was refused permission to enter the region and so does not get to see the Victoria Falls. Mavuma manages to bring the semi-delirious Leask back to Shoshong where Reverend John Mackenzie and his wife Ellen nursed him back to health after which he returns to Potchefstroom.

Leask’s journey to the Zambezi from February or March to 12 September 1869; “My Fourth Hunt”[xiii]

Leask made himself three small books from blue notepaper each measuring 21 x 13 cm (8.25 x 5.25 inches) for this journey but kept no record from leaving Potchefstroom in February / March 1869 until 8 June 1869.

Feb / Mar 1869 – “The day on which we left Marico we were met by some fifteen or twenty men who were returning from the Tati goldfields. They had found no payable gold and declared it was an entire swindle; and some of them were going to do something awful to all newspaper correspondents and editors. And by the way considering the amount of embellished truth and bare-faced lies that are published in some papers about the said goldfields, a little wholesome horse-whipping would not be amiss somewhere…Left the Limpopo and turned north towards Bamangwato.[xiv] Met some more disheartened diggers returning. They all had specimens of gold, both alluvial and in the quartz, but are of the opinion it will never pay.”

Leask encounters a group of young miners from Glasgow going to Tati to work for the Glasgow and Limpopo Company. They are led by a Dr Coverley whom Leask consults professionally. “He told me I was more hypochondrial than ill” and suggested that Leask be their guide and he would be Leask’s doctor. This suited both parties and Leask’s health rapidly improved.

At Shoshong they presented Chief Macheng with a turkey; “Still I detected the old natives of the court stealing some very distrustful side-glances at him…the Chief however was thankful and said though he had not previously seen any turkeys he had heard of them.”

“It is eight days trek from Bamangwato [Shoshong] to Tati. Some two or three years ago game of all sorts were numerous along the road. It was easy to find giraffe, buffalo, eland and even rhinoceros, but now the country is so much hunted by the natives, who are well supplied with guns, and there is twenty times more traffic on the road, so the game is rather scarce.” Nevertheless Leask manages to shoot a giraffe for meat.

1 Apr – they reach Tati, but the alluvial workings are disappointing with only 20 – 30 diggers left; many have already gone, some for Mashonaland, or what is called the northern goldfields. Leask leaves on 3 April with a light wagon and eight oxen to assist Reverend and Mrs Thomas who had been ill with fever for three months. Manyami at Makobi’s kraal, agreed not to detain him as he knew him as a friend of the King[xv] and the Thomas’s were sick and needed medicine. Manyami said Mzilikazi needed a present of a gun, but Leask knew this was humbug and proceeded on his way.

11 Apr – Natives told Leask that all the white people at Inyati had smallpox and they might all be dead. He did not believe them and reached Inyati Mission. A digger had died of fever, five more were sick [four of whom subsequently died] as were the Thomas family. “His wife, poor woman, is very sick though moving about; I never saw such a walking skeleton…and evidently ‘ere long will add another to her family. Her husband sick and shall I say, silly through sickness; two of her three children just recovering from sickness…the house a heap of mud and rotten thatch, alive, literally, with rats and ants.”

Leask writes: “And why all this sickness and misery? Simply carelessness and ignorance. The houses at Inyati are enough to breed plague in wet weather. Houses did I say? They are hovels of mud and rotten thatch swarming with rats, mice, lizards, ants, etc. Every building on the place should be set on fire. All the diggers who are sick slept some time in an old tumble-down place which has not been inhabited since John Moffat left it some four or five years ago. All that slept in the house caught the fever, none of those who did not sleep in the house caught it. Again, not one of them knew how to treat the disease. No more did Thomas, and when told what to do by W- and P-, both of whom had had the fever themselves and seen many cases, he paid no attention to their advice.”

“If they [London Missionary Society] cannot send medical men to every mission, let them at least give their missionaries some knowledge of diseases and medicine and especially of midwifery.”[xvi]

End April – At Tati “all the old experienced diggers who came up in company with me had returned and several of the ’green horns’ of ‘new chums’ as well. They wanted alluvial and did not consider themselves in a position to attempt quartz digging…It seems to be generally believed that the old diggings are the work of white, or at least civilised people. If so, it was probably the Portuguese and supposing it to have been done by them, why should they come to the Tati, seeing that the Mashona country is much nearer their settlements?[xvii] I fancy however that these old diggings have been worked by the natives and that they bartered the gold to the Portuguese.”

Leask returned to Tati with a strange letter from Reverend Thomas. Mzilikazi had died in September 1868 and the regency was in the hands of Nombata. Although Mzilikazi had been well-disposed to Europeans, most of the amaNdebele were not and Mzilikazi had trod a delicate line. But with his death Thomas took upon himself sole discretion to grant mining concessions in return for an annual payment; apparently Thomas was trying to assist Sir John Swinburn to obtain a monopoly over the goldfields for his company London and Limpopo Gold Mining Company.

“He [Thomas] told me the contents of the letter and I enquired whether he was in a position to make such a grant seeing that the feeling of the Matabele was plainly hostile to anything of the sort. He quietly informed me that he could do just as he pleased, having full power from the Matabele chiefs. I was silenced, but not convinced.” Leask clearly thought Thomas was over-reaching himself and cautiously sounded out the izinDuna’s “and the chiefs said that until they get a King they cannot grant more liberties to white people than Moselekatze granted. What he allowed white people to do they can do still, but no more.”

10 May – Leask, Gifford, Dr Coverley, Henry Ogden and Hudson leave Tati to hunt on the Zambesi river. They trek to Mangwe and take John Lee’s Road to Bukwela’s kraal where they met with Zietsman, Byles and Meyer. “When within half a day’s journey of Manyami’s we turned north and skirted the Matabele country.”

8 June – they reach Summamolisha[xviii] and camp with Zietsman’s party nearby. “We mustered pretty strong, being nine white men, one half-caste and over one hundred and fifty natives of different African tribes.” They hunt in various groups along the Gwaai and Shangani rivers: “hoping to find a hippopotamus, saw only a crocodile. It is high treason to shoot the latter in this country. The natives believe, or profess to believe, that any person who kills a crocodile is guilty of witchcraft and uses the heart and other parts of the animal for bewitching purposes.” Leask kills his first lion: “Fired and sent a two ounce bullet through him.[xix] He went about a hundred yards and lay down. The grass was long; we heard the lion but could not see him. The natives were afraid to approach and I exhibited no extra amount of daring. One native got up a tree from which he fired. The lion growled in reply. We gradually but slowly moved towards him and came up in time to see him expire.”

18 June – they hunt in the area where the Shangani joins the Gwaai river – much game is seen, but few elephant and those that are seen mostly get away.

23 June – “We have been sixteen days from the wagons and brought only about 113 kgs (250 lbs) of ivory.” The servants who stayed at the wagons have spotted tsetse-fly, so they move camp about 10 kms (6 miles) south. “There is no living animal of which the African hunter and traveller stands in so much dread as the tsetse-fly.”

29 June – “Today we have been busy making preparations for another hunting expedition into the “fly.” This time we intend going in a northerly direction and some of us intend – all being well – to see the Zambesi before we return.

This last week has been one of rest but not of idleness, what with making and mending shoes, repairing damages done to clothing and darning stockings, cleaning, mending and altering guns, making bullets, washing clothes, baking and boiling, in fact doing numbers of necessary jobs. We also had a day’s hunting with the horses; that is if riding in search of game and seeing none can be termed hunting…”

30 June – Leask, Gifford, Coverley start to walk to the Victoria Falls leaving Ogden and Hudson at the camp. They travel via Dett, where they meet Byles and some of his companions and continue via the Inyantu, Shangano and Deka rivers. Gifford stays at the Shangano river to hunt and to avoid frightening local people on the Zambezi with his amaNdebele servants.

2 July – They spent the night at Malonga Well [just north of Hwange National Park at Dett] where “we found three rhinoceros quietly enjoying an afternoon’s nap under a bush, one of which we shot. The beast was scarcely dead when thirty hungry heathens commenced cutting and hacking in a very careless, excited and noisy manner; a few minutes sufficed for dissecting purposes.”

3 July – “Our day’s march was a very short one, though we travelled three hours. The country is extremely rugged and though picturesque it is uncomfortable travelling. The hills are merely separated by narrow gorges, so that it is one continual up and down. Game paths are a great aid, but they don’t always lead in the right direction; they lead us about like a ship beating to windward.”

4 July – they cross the Inyantuwee [Inyantue – a tributary of the Gwaai river] “Followed up along the banks of the river for some time and at noon halted when the guides told us that we must sleep there or die of thirst, for the next water was very far. Started again and two hours brought us to a pool of water by which we encamped.”

6 July – “this morning we were early on the path, or rather scrambling among the rocks. Passed through a very picturesque gully…An hour’s walk brought us to a river which is named Shangani. [This is actually the Gwaai which has joined the Shangani river some fifty kms to the south-east]

7 July - “This morning we started on our several courses. Gifford with twenty Matabele went down the river in search of elephants; Dr Coverley, myself and fourteen natives for the Zambesi. After three and a half hours walking we came to a fine river of beautiful running water. This river at its source is called Deka; here the natives call it Ngando. I crossed it last year a few miles below its source and the stand place for wagons at the end of the road to the Victoria Falls is about a day north of the source. The remainder of the road to the falls has to be travelled on foot owing to the country being infested by the tsetse-fly.”

8 July – Leask and Coverley reach the Zambezi river. “Followed the paths along the Deka for three and half hours, crossed to the east side of the river…worked our way down it as best we could and after much labour and many tears and scratches, we got to the end of the gorge and the south bank of the Zambesi…Tired, hungry and in a very bad temper with everything, especially the thorns and our guides.

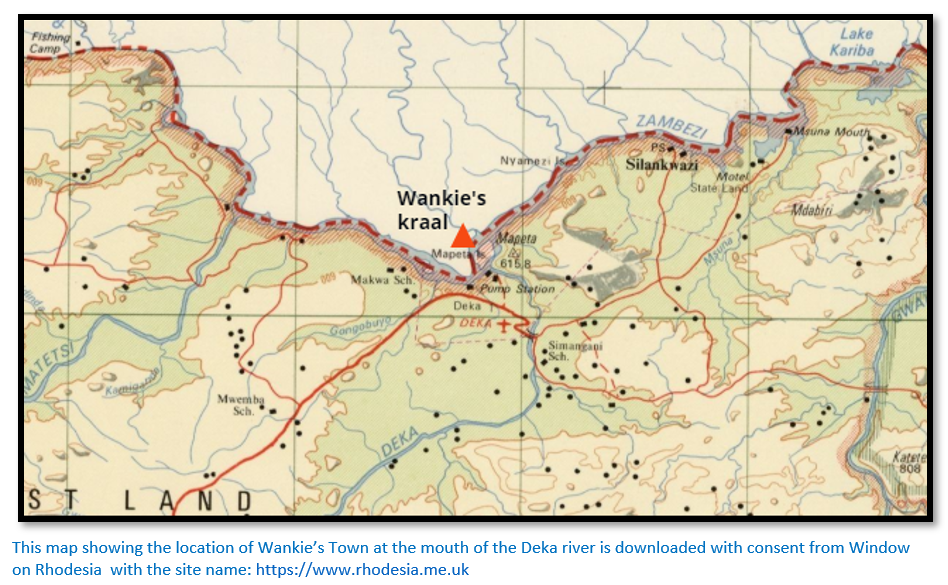

Certainly it bore no resemblance to the fine large river which Livingstone’s and other person’s descriptions had led me to expect. The stream was only about fifty yards broad, the river bed was rocky and the banks were rugged stony hills covered with scrubby straggling bush…The guides when they saw the river could not tell where we were; only they said we were below Wankie’s, how far they could not say.”

9 July - “The natives who slept by us last night offered their services to guide us up to Wankie’s, which offer accepted and started. It was warm walking and in some places rather rugged. We had to keep in the river bed, the bush being too thick for us to walk on the bank. There were gardens all along the river on the opposite bank. At midday we came to where the river Deka joins the Zambezi, which is nearly opposite Wankie’s. There is an island below the junction which dams up the water.

We were told to walk up the river until we found a crossing place for they could not – which meant would not – bring a canoe to where we were. There being no alternative, we turned up the river and had gone about a mile when our volunteers this morning said we must cross there. Half-an-hour’s walk brought us to the ferry and then we had time and opportunity to admire the river. The breadth varies, say, from three to five hundred yards. Above and below are islands which are covered in large trees. On the opposite bank, in a bend of the river, is Wankie’s town. His gardens are by the riverside and are studded with baobab trees.

A canoe came across and Wankie’s son came to hear our news and see whether we were Englishmen or Boers. As he and I were acquainted last year, matters were soon all right. Went through to see old Wankie. Found him very kind and we were soon fast and everlasting friends. Exchanged gifts, the one I gave him, of course, being the larger.

His town is a poor place, very small and the huts miserably little badly made things.”

10 July – All last night was given to eating, drinking, music and dancing on the part of our people. We slept little from the noise; they slept none.

11 July – “Did a little trade and took a long time over it. I fairly tired out the natives. Offered them a price in beads and brass wire for some ivory. They waited hours in hopes of getting more, but I was determined to let them see that I could be firm. Eventually they took the offer and were satisfied.”

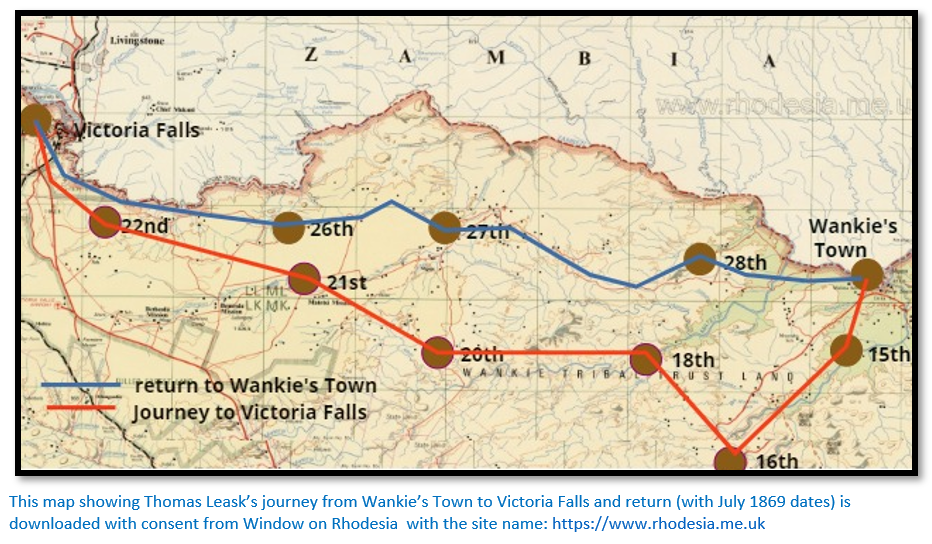

15 July – “…we intend to go and see the falls but must first return to Gifford and let him know so that he can go back to the wagons. Got some guides from Wankie and started in the afternoon.”

16 July – “All the people along the Zambesi are terribly afraid of the Matabele, consequently we could not take our guides to where Gifford and his people were…Had hard walking for six and a half hours and got to Gifford’s camp [at the Shangano river] in the afternoon. Found him quite well and glad to see us. He had been hunting ever since we separated and found elephants only once; he shot one.” Leask and Coverley tell Gifford to return to their main camp for which he starts the next day; Leask and Coverley plan to walk to the Victoria Falls.

18 July – “Walked six hours and came to the river Matetsi…It is tough tiring work clambering up and down these hills.” As the next day is Sunday they rested.

20 July – “Started early and walked over more agreeable country…At midday…our guides took us a little away from the path to show us some engravings on a large sandstone.” [the description is included in the article Bumbusi Ruin and Rock engravings under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Wallis the Editor of Leask’s Diaries consulted Dr J. Desmond Clark, the famous archaeologist, who favoured the Bumbusi engravings. However from Wankie’s Town on the Zambesi it took one and half days to reach Gifford’ camp i.e. forty kms. Six hours walk to the north-west took Leask’s party to the Matetsi river. Then a morning’s trek to the engraving site. They are clearly north of the present-day town of Hwange; the Bumbusi engravings are fifty kms south-west of Hwange and a long way south of the Matetsi river which rules them out.

21 July – “All the forenoon our course was over very rugged country. We came to the river Matetsi again [probably the Mbija river, a tributary] Here the scenery was grand. The river ran through a deep gorge and we had difficult work to scramble down and climb up the precipices…at midday we got out from the hills in the sandy country…shortly before sun we came to an open valley called Kingora and in it found a large pool of water, Jiumba…Time walking 6 hours = 30 kms (18 miles)” [this is Chewumba pan near Matetsi mission, I believe]

22 July – “…We had our first view of the Victoria Falls, or rather the vapour of the falls. We saw them at 11am and they lay north-west…The Zambesi was quite close to us and we proposed walking up along it but the guides declared it is almost an impossibility to do so, there being so many kloofs and precipices. Took their advice and kept some distance from the river. 5 hours = 24 kms (15 miles)” [the Batoka Gorge is just 12 kms north of Chewumba pan]

23 July – “After walking three and a half hours we reached the Victoria Falls and felt satisfied…After spending some hours at the falls and getting well drenched with the spray we went about three miles up the river to the ferry. Fired some shots and the people came through at sundown. Asked them to bring some meal for sale. They promised but brought none.”

Leask had read Livingstone’s and Baines’s descriptions, but found the reality: “much different from what I had pictured in my mind’s eye. The placidness of the river a little above the falls, the awful yawning gulf in which the tremendous body of water falls, the deafening roar and the clouds of thick vapour which ascend and come down in a perpetual rain, the drops glittering in the sun like a shower of diamonds, the rainbows dancing about the thick evergreen dripping trees and bushes which cover the brink of the chasm opposite the fall, all combine in making a scene that for terrible grandeur cannot be surpassed.” He was disappointed in one thing: “the falls cannot be seen at once they are so broad and the vapour is so dense that they can only be seen a bit at a time.”

25 July – They leave the Falls: “Started early in the morning. Had a fine view of the Zambesi some miles below the falls where it takes a sharp turn and roars along in its narrow bed.” Time walking 7.5 hours = 35 kms (22 miles) They are retracing their steps walking back to Wankie’s town.

28 July – “A walk of three and a half hours brought us to the Matetsi river where it joins the Zambesi and two hours more brought us to Wankie’s. After waiting about an hour they came across with a canoe. I went over to Wankie and bought a goat which was soon slaughtered and part of it on the fire and before long we were slackening our belts – we had been repeatedly finding it necessary to tighten them. Wankie was very kind and glad to see us – at least he said so and I believe him for he knows how to beg.”

The 4 day journey from Victoria Falls to Wankie’s Town took 24 hours of walking which indicates a total distance of 116 kms (72 miles)

4 Aug – Having left Wankie’s Town on 30 July Leask and Dr Coverley reach their wagons at Tshuma Maleesa [Malisa] only to find the camp-site deserted. A note tied to the branch of a tree informs them tsetse-fly have been spotted and the ox-wagons have moved to a new site 20 kms (12 miles away) at Linkwasha pan [in the very south east of Hwange National Park] Next day they shot a lion and a bull elephant.

8 Aug – “There are a good many fine old bull elephants in the neighbourhood [of Linkwasha pan] but they are very cautious and wide-awake. During the night they come out to drink at some one or more of the waters and before morning they are again in the thickets which are in many places impenetrable even on foot. Hunting in such a country is both useless and dangerous.”[xx]

22 Aug – “Some Hottentots and Griquas who had been hunting in the neighbourhood for the last month or six weeks trekked up to our camp while we were out hunting…Their party consisted of an old rickety wagon , both front wheels of which had been mended in a very rude manner…The [ten] children were honestly clothed, their dress being that of nature, with the simple addition of a thick crust of dirt. The whole squad had innumerable wants, all of which it was a pleasure for me to supply, so long as they had ivory.”

25 Aug – move off down the Linkwasha valley to the Nata and Maitengwe rivers.

2 Sept – “Arrived at the river Nata about a couple of hours before sundown.”

3 Sept – “A forenoon trek of about four hours brought us to another longish river, or more correctly a river bed of deep, dry, loose, white sand.” (Tegwani river]

4 Sept – “In the afternoon we got into hilly country again, which is quite a change. These hills are very grand and many of them are curious heaps of bare rocks with a few bushes and some fine cactuses growing in the fissures. These hills and valleys extend over a great tract of country, which is generally termed the Makalaka hills from the tribe that once inhabited them, a few of whom are still left.” The land rises and crosses the 1,200 metre gradient. They manage to buy some meal; the first their servants have enjoyed in three months having lived entirely on meat during the journey.

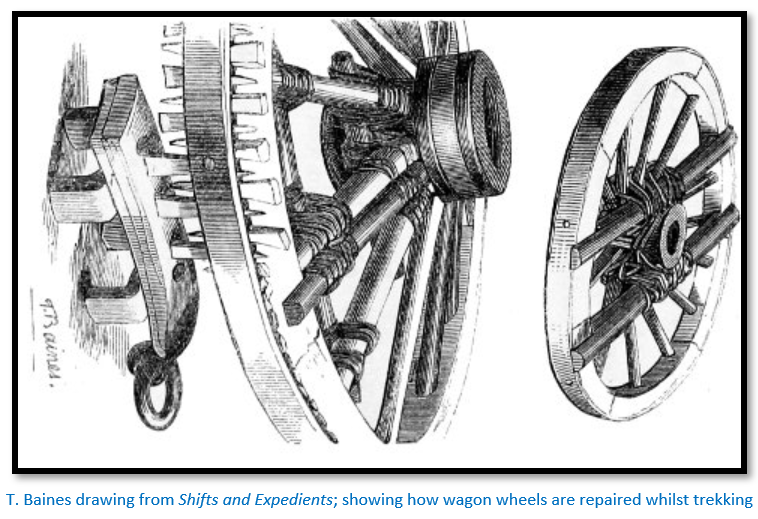

7 Sept – “One of the wheels of Gifford’s wagon has for some days been with difficulty kept from tumbling to pieces, so to prevent an accident he set about making a new set of spokes for it. A nave band was burst and for the purpose of welding it a native smith was employed. He brought his two bellows made from two goat-skins, as described by Livingstone and others, a smooth stone for an anvil and some charcoal. The smith engaged to iron to a welding heat but would attempt no more. However, he could not reach the necessary heat and was given beads for his good intentions.”

9 Sept – “The last of our Matabele servants left us yesterday for the purpose of returning to their homes, as we intend to shape our course from here to the source of the river Tati…A long trek from there brought us to a little river, one of the sources of the Shashi, [Shashe] where we slept and had to dig for water.” They have crossed the watershed and the rivers now flow south to the Limpopo.

10 Sept – “Trekked a good day. Crossed the Shashi several times and slept away from water. An hour’s trek brought us to the Tati and some three hours down it we outspanned, where our cattle could enjoy the luxury of a good drink of pure water.”

End Sept – They trek down the Tati river to the Tati settlement having killed about sixteen elephants and Leask returns to Potchefstroom: “where I disposed of my ivory and other goods picked up or bought in the interior. This completed I rested for some time and visited my old friends. After two or three months I made preparations for another trip to the interior which proved to be my last.”[xxi]

References

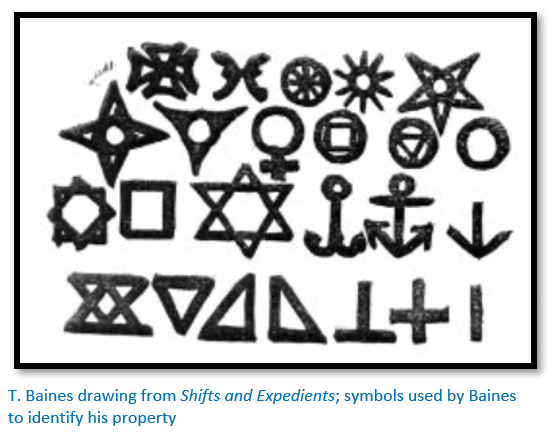

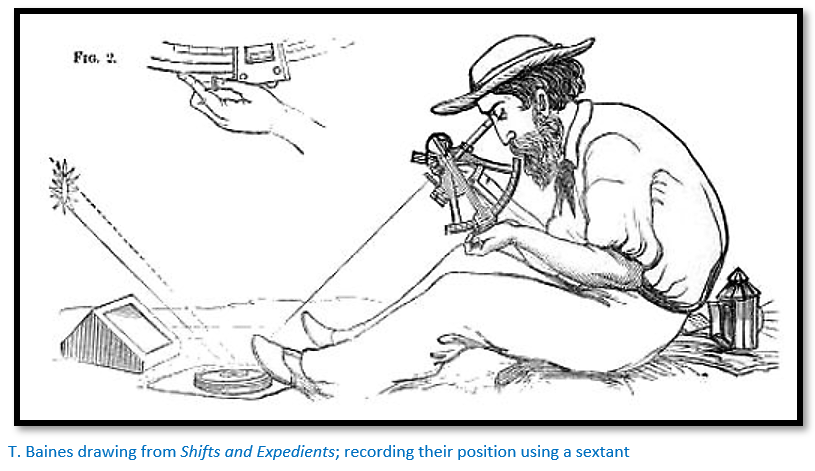

W.B. Lord and T. Baines. Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life Travel and Exploration. Horace Cox, London 1871

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town 1966

H.L. Tangye. In New South Africa – Travels in the Transvaal and Rhodesia. Horace Cox, London 1896

J.P.R. Wallis. The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865-1870. Chatto & Windus, London 1954

[i] The Southern African Diaries, P125

[ii] The Makgadikgadi Pan once a vast inland lake. The main water source is the Nata River, called Amanzamnyama in Zimbabwe, with its source near Bulawayo; the Boteti River from the Okavango delta also supplies seasonal water.

[iii] Baobab tree (Adansonia digitata)

[iv] Khoisan hunter-gatherers

[v] The Nata river flows into the Sua pan, on the eastern side of the Makgadikgadi salt pans.

[vi] William Charles Baldwin – a legendary hunter who wrote African Hunting from Natal to the Zambesi, Including Lake Ngami, the Kalahari Desert, &c., from 1852 to 1860

[vii] Khoisan hunter-gatherers.

[viii] The Westbeech Road cut by George Westbeech from Old Tati.

[ix] Tsetse-fly carries nagana which is fatal to oxen and horses.

[x] Wankie is a Makalaka chief living on the north bank of the Zambesi river below the confluence with the Matetsi river and about three days walking downstream from Victoria Falls. Hwange the town is named after him but is on the coalfield, not the river.

[xi] Van den Berg himself died of fever the next year.

[xii] The present consists of a gun, a bag of powder, a bar of lead, a box of percussion caps and a suit of clothing.

[xiii] The Southern African Diaries, P141

[xiv] The old name for Shoshong

[xv] Mzilikazi died on 9 September 1868 and Lobengula had not yet been made King.

[xvi] The Southern African Diaries, P148

[xvii] The Portuguese settlements at Tete and Sena on the Zambesi river.

[xviii] This stream flows into Dopi vlei is in the south of present-day Hwange National Park and about 30 kms from the Gwaai river

[xix] An eight bore smoothbore.

[xx] The Southern African Diaries, P181

[xxi] Ibid, Pxxxvi