Home >

Matabeleland North >

Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone

Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone

The Zambezi expedition

There is no consistency in the Victorian descriptions of the 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition: Dr Livingstone’s Expedition, Livingstone or Zambezi Expedition, The Central African Expedition; they all refer to the mission along the final four hundred kilometres of the Zambezi river between Tete and the Delta, or in the lower two hundred kilometres of the Shire river.[i]

The initial plan for the Zambezi Expedition was to proceed as rapidly as possible up the Zambezi river and beyond the Victoria Falls. There to begin to setup the infrastructure for future cotton gins and sugar mills, to begin planting crops and exploring the region and cataloguing the natural resources with an eye to future trade.[ii]

However in the book Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambezi and its Tributaries and of the Discovery of Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864 which is based on the journals of David and Charles Livingstone “every failure and setback for the Expedition is in one way or another attributed to Portuguese meddling”[iii] along with calls for British action against the slave trade. Clearly this was an attempt to divert the public’s attention away from Livingstone’s poor leadership and other errors, such as assuming the Zambezi was navigable.

Most spellings have been changed to those in current use. (i.e. Lake Malawi for Lake Nyassa)

Early life of Thomas Baines

(John) Thomas Baines (27 November 1820 – 8 May 1875) was born in King’s Lynn, Norfolk; the second son and one of three surviving children of Mary Ann Watson and John Thomas Baines, a master mariner. His father and maternal grandfather were amateur artists, his brother Henry a professional; Thomas was apprenticed to a painter of heraldic arms on coach panels, a craft he learnt from the heraldic painter William Carr.

Sail for South Africa

In 1842 when he was 21 years old and wished to see more of the world he sailed for the Cape Colony aboard the Olivia arriving on 23 November 1842. For his first five years in Cape Town he worked first as a painter for a cabinet-maker and then as a scenic and portrait artist becoming well-known for his many attractive seascapes in oils and watercolours usually featuring the backdrop of Table Mountain.

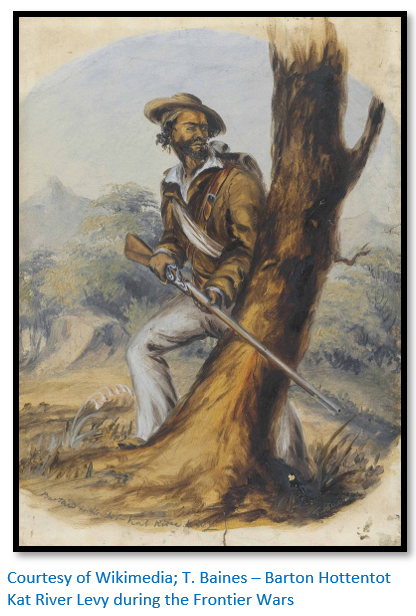

The young man, however, tired of repetitive painting and in 1848 headed for the Eastern Cape—to Grahamstown and its hinterland. Baines based himself in the Eastern Cape between 1848 and 1853 and from there he undertook three journeys to the interior. The first, in 1848, took him beyond the Orange River; on the second in 1849 he travelled beyond the Great Kei River and over the Great Winterberg mountains; in 1850 he made an attempt to reach the Okavango swamps of northern Botswana. Returning in 1851 he found Grahamstown almost in a state of siege and was offered a post as artist-draughtsman to the forces under General Somerset 1852 during the so-called Eighth Frontier War. He made many sketches of the action, some for the Illustrated London News, frequently at great personal risk.

Fortunately he kept a regular diary and a rich daily account of his experiences and impressions survives. “Of adventurous disposition, he mingled with adventurers, and the pictures he painted in the course of his travels are amongst the finest mementoes Southern Africa has of the days of frontiersmen and ivory hunters.”[iv] There was little demand for paintings in a frontier society and for many months he wandered alone and on foot into the more remote parts of the colony and recorded the culture and habits of the Xhosa people who offered him food and shelter. During this period Baines accompanied a group of hunter-traders into the Transvaal and learned about the river systems and lakes in what was then referred to as the ‘far interior’—places such as present-day Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia, which he was later to visit and record. Baines proved himself to be a careful observer of humans and places, and a physically robust and resourceful young man.

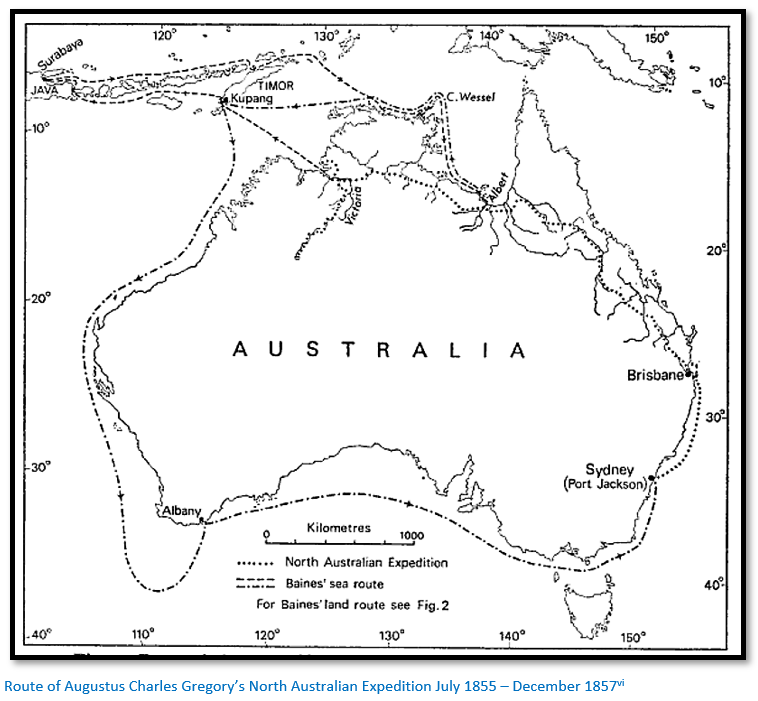

In 1852 when Baines returned to King’s Lynn he gave a number of public lectures and exhibitions in his home town and published Scenery and Events in South Africa, but also went to London and worked at the Royal Geographical Society on a map of Africa, in consultation with the cartographer John Arrowsmith.[v] His artist’s eye and field knowledge earned him the respect of those he met and suggestions were made that he accompany Augustus Gregory and his team on an expedition across northern Australia, sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society.

Australian expedition of 1855-57 under Augustus Gregory

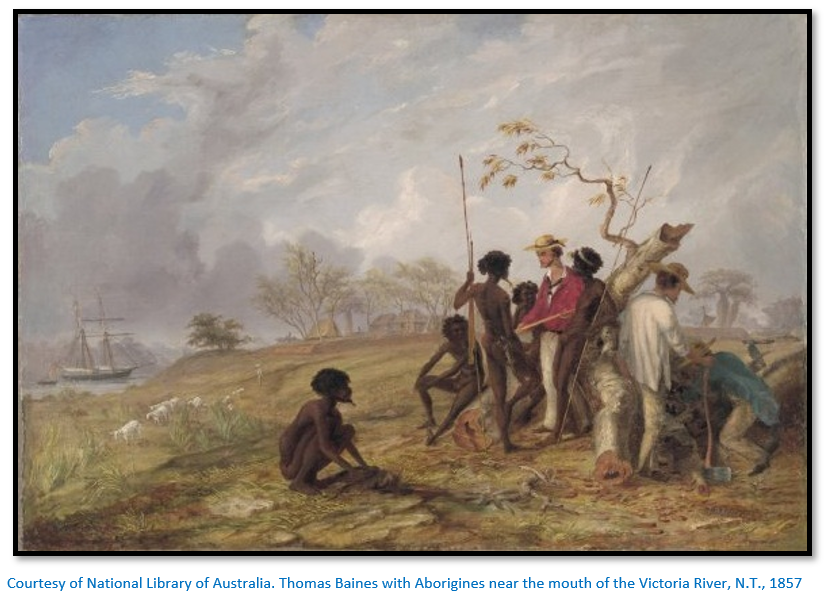

In 1855 Baines joined Augustus Gregory’s 1855–1857 Royal Geographical Society sponsored expedition across northern Australia as official artist and storekeeper sailing from Liverpool to Port Phillip on board the Blue Jacket which made a record voyage of 69 days and joined Gregory in Sydney. The expedition’s purpose was to explore the Victoria River district in the north-west and its suitability for colonial settlement by establishing the extent of its agricultural land and collect details of the region’s rivers.

In the event, although Baines did not accompany Gregory in the land party on the adventurous overland trip, his association with the North Australian Expedition was the highpoint of his career and his valuable contribution to its success was acknowledged by Mount Baines and the Baines river in the Northern Territory being named in his honour.

Baines was often left in command at Depot Creek when Gregory went off exploring with a smaller and more mobile mounted detachment. He organised the stores sourcing supplies by sea journeys to Java and Timor, had the boats repaired and returned the expedition staff to Sydney by sea via the westward route, almost circumnavigating Australia in a long boat and many fine paintings and sketches survive from this journey. His adventures, too numerous to review here, earned him the following praise in Gregory’s official report: “I consider it my duty in this place to recommend his [Baines] conduct throughout the Expedition for the approval of his Excellency, as he has shown considerable energy and judgement in carrying out his instructions and a constant desire to carry out the object of the Expedition.”[vii]

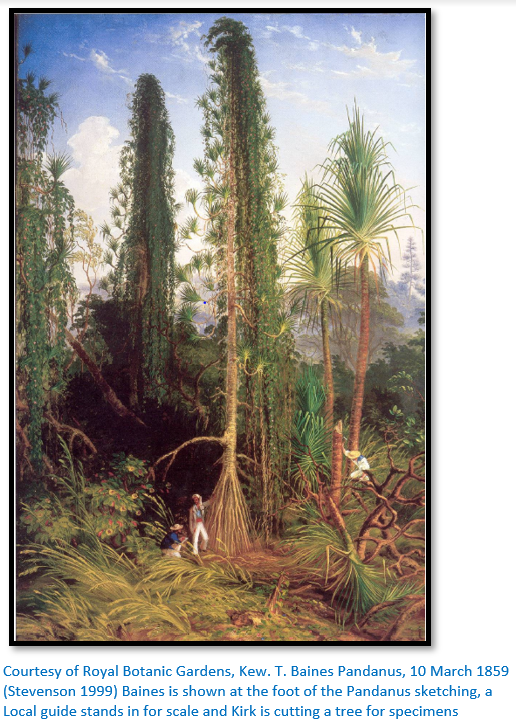

Baines achievements

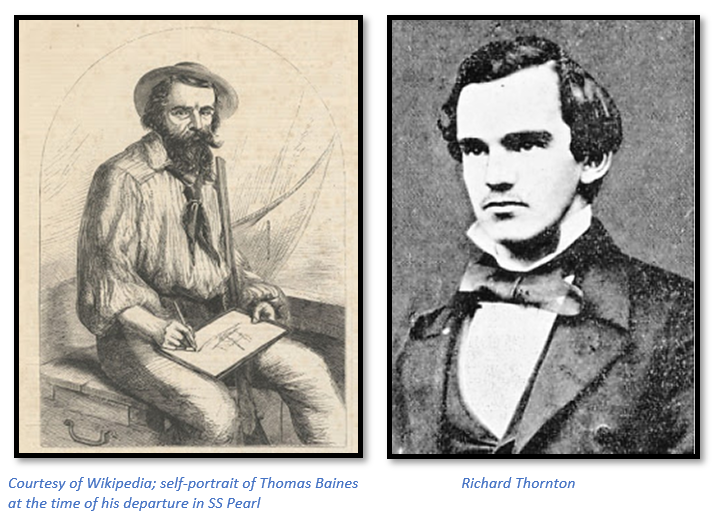

Seldom without a pencil and sketchbook to hand, Baines produced a graphic record of Gregory's expedition unparalleled in contemporary Australian exploration.[viii] Always an observant naturalist, his washes and sketches of plants were well regarded by the eminent botanist Sir William Hooker. His paintings of Australian animals and insects and the Aborigines portraits he painted were appreciated by zoologists and anthropologists. Seventeen plant specimens in the collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, bear his name, as does Bolbotritus bainesi, a new genus of beetle he discovered. His reputation – not only as an artist, but as an accurate and scientific geographer, was spreading in scientific circles, in both England and Europe.[ix]

He had done well and earned himself a good reputation for organisation in the face of an unknown land, an unhealthy climate, often uncongenial and uncooperative companions, the hostility from Aboriginal Australians and the difficulties of provisioning stores and ships. He left Sydney in July 1857 and was elected Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and received its gold medal in 1858.

David Livingstone’s fame

In 1856 David Livingstone returned to England a national hero after his journey from the port of Luanda on the Atlantic Coast of Angola to Quelimane in Mozambique where the Zambezi River meets the Indian Ocean. The next year he published a book Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa which sold a remarkable 70,000 copies. With the huge amount of public support behind him, he persuaded Lord Clarendon, the Foreign Secretary and Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister to sponsor an expedition by the British Government to investigate the navigability of the Zambezi River and open it up as an ‘economic highway’ through Portuguese-occupied territory to allow cotton and sugar to be grown in large quantities on the floodplains of the river and to destroy the slave trade. He hoped: “to introduce Commerce, Civilization, and Christianity to the lands of Zambezi River and Lake Malawi.”

The 1858-59 Zambezi Expedition under David Livingstone

Because of his excellent work in Australia, Baines was invited to accompany the renowned missionary–explorer David Livingstone on the 1858–59 expedition to assess the navigability of the Zambezi River.

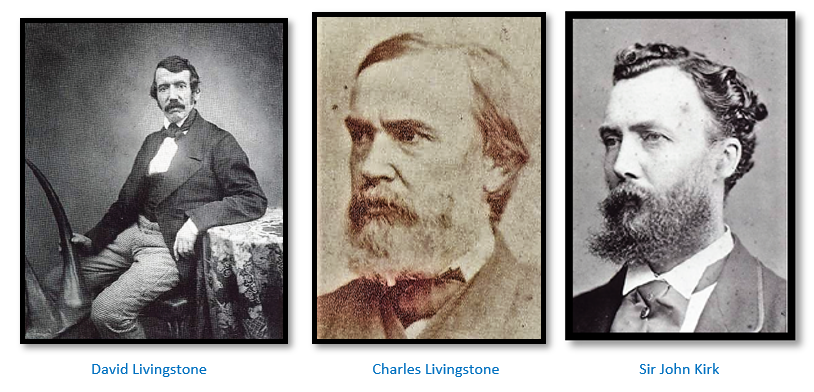

On the 10th March 1858, Livingstone sailed from Liverpool in the S.S. Pearl with his brother Charles as general assistant and ‘moral’ agent, Commander Norman Bernard Bedingfield of the Royal Navy as second-in-command, naturalist and medical doctor Dr John Kirk, geologist Richard Thornton, engineer George Rae and Thomas Baines as artist and storekeeper; en route it stopped in Freetown, Sierra Leone and Cape Town, South Africa and then the Zambezi river mouth.

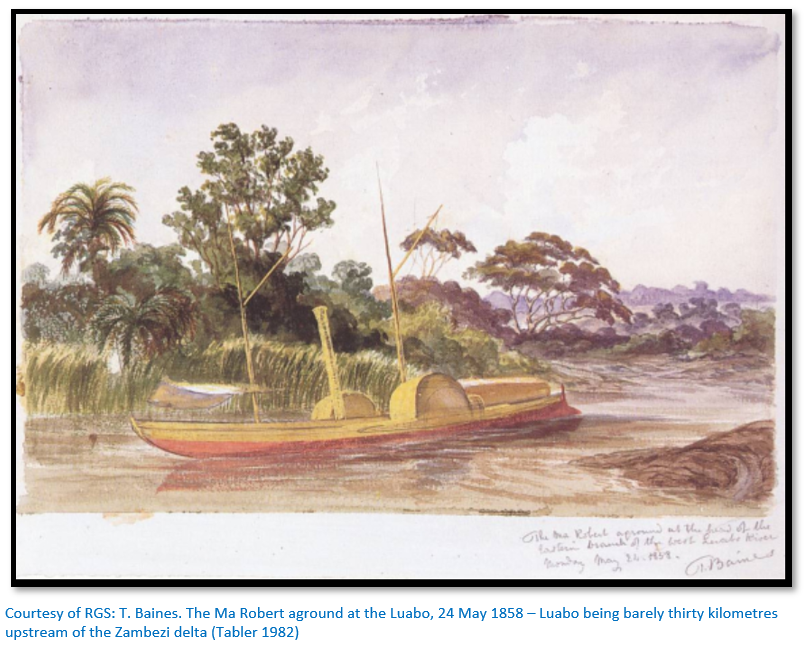

May — November 1858 - The S.S. Pearl arrives at the Zambezi delta on 14 May 1858

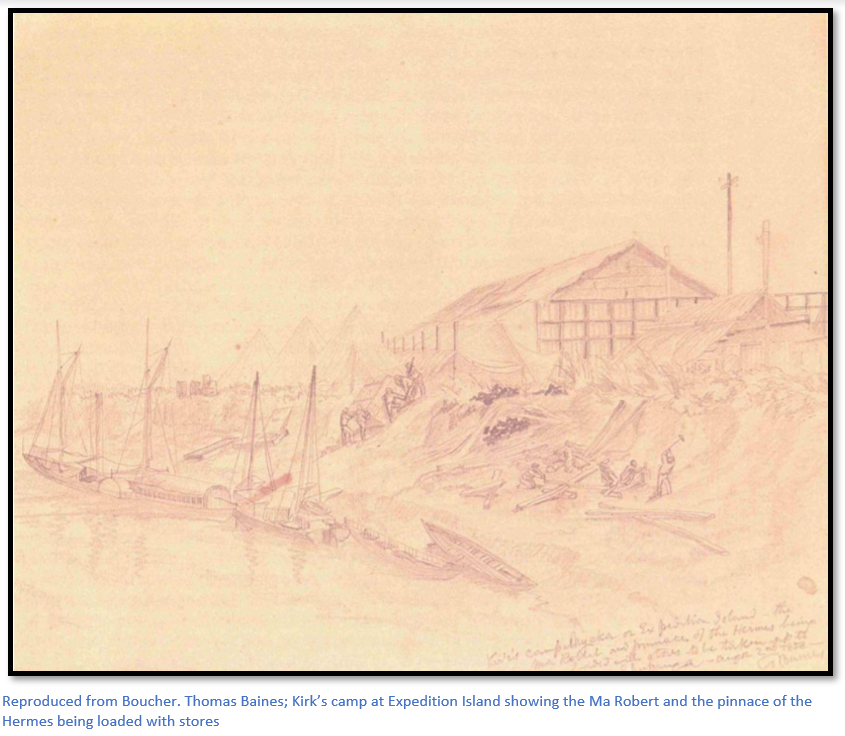

The party prepared for their travels and explored the area. Navigation charts were poor and the main channel was only discovered on 11 June. The original plan was for the S.S. Pearl to take the Expedition’s stores to Tete within a week or two and then return and continue to Ceylon. But the river was too shallow, so the expedition faced months of ferrying stores upriver; they were unloaded on a small island (Expedition island) on the delta for the Ma Robert to take them to Tete using Chupanga (formerly Shupanga) and Sena as depots with the base camp at Tete. Norman Bedingfield left at the end of July due to differences with David Livingstone.

November 1858 — January 1859: the Zambezi River impossible to navigate above Tete

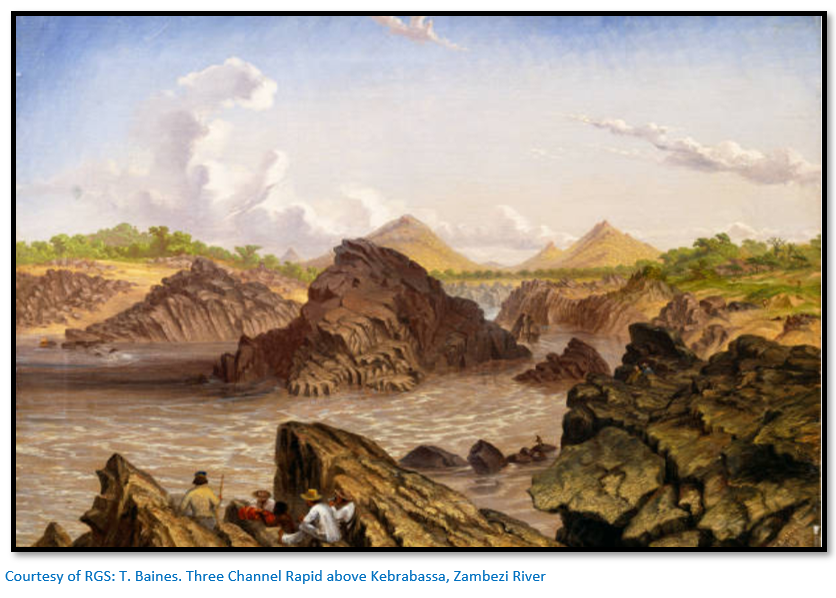

Equipment was initially scattered at Expedition Island, Chupanga, Sena and Tete, but by early November most stores and staff were gathered at Tete. Two demanding expeditions by foot upstream from Tete proved that the primary aim of the expedition was doomed from the outset. On his earlier journey down the Zambezi in what is now Mozambique, Livingstone heard about, but skirted around and did not view, a set of rapids known as Cahora Bassa, starting ninety kilometres above Tete. The cataracts and rapids that Livingstone had failed to explore on his earlier expedition made it impossible for any vessel to sail up the river even at full flood at the end of the rains.

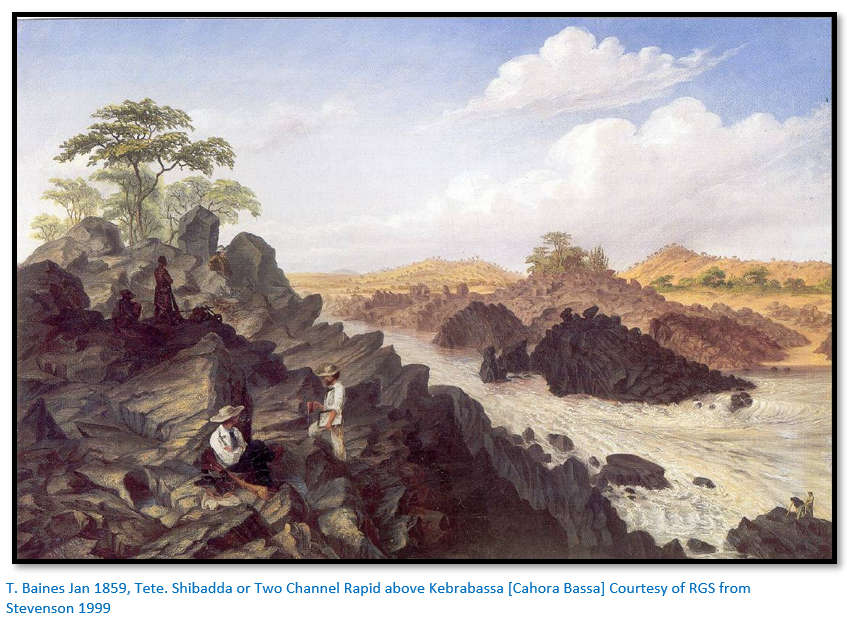

Baines and Charles Livingstone were told to visit Cahora Bassa during the floods in January to see if the higher water made it passable; it did not. They made the ninety kilometre journeys to the mouth of the gorge on 8 - 13 November and 22 November – 8 December 1858; the second trip was guided by José Anselmo de Santanna who was leading the Portuguese prazo resettlement above Tete to Zumbo. From 21 December David Livingstone and Kirk went up the Shire river to view the region.

Richard Thornton’s dismissal

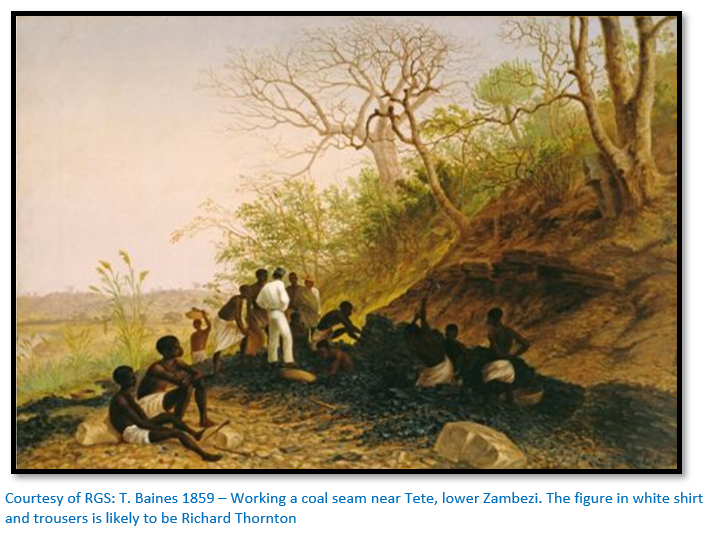

The geologist Thornton explored the Moatize area a few kilometres north of Tete and wrote a favourable report on its coal seams which the Ma Robert was able to make use of in her boilers. Baines and Thornton had been exploring the natural resources around Tete but were often sick with malaria and Charles Livingstone delivered malicious reports of their underperformance. They often found themselves alone at Tete base camp, unsupervised and discouraged, without medical care, suffering malaria, fever, dysentery, sores and prickly heat. Thornton lacked the energy to keep up his geological work and Livingstone accused him of being ‘idle’ and of disobedient writing: “[Thornton] has been incorrigibly lazy, seems to have no taste for geology and works none.”[i]

However it is more likely that both Livingstone’s were jealous of Baines and Thornton because they had formed constructive relationships with the Portuguese at Sena and Tete who had been in the area for hundreds of years.

Baines was accused of stealing supplies and Richard Thornton was dismissed on 25 June 1859 but stayed on at Tete and accompanied a Portuguese caravan to Zumbo before making his way to Zanzibar and joined Carl Von der Decken’s expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro. He returned to the Zambesi in 1862 and re-joined the Zambezi expedition in January 1863; Drought and famine worsened by tribal warfare brought about by slaving had resulted in the expedition running out of supplies. Thornton trekked 150 miles overland to Tete and it was only his friendship with the Portuguese that enabled him to obtain sixty goats and forty sheep. He returned severely weakened by fever and dysentery and died on 21 April 1863, on board the river-launch Pioneer, aged 25 years. He was buried the next day under a large baobab tree near the cataracts, now Kapachira Falls, on the Shire river.

Sir Roderick Murchison wrote: “So gifted and rising an explorer – had he lived, his indomitable zeal and great acquirements would have surely placed him in the front rank of men of science.”[ii]

February – November 1859; the Expedition receives an extension; Baines is dismissed

David Livingstone and Kirk returned to Tete on 2 February 1859; the Shire river appeared navigable and the Portuguese at Sena informed them of a large lake upstream. They wrote up reports before departing once more up the Shire river on 14 March.

On their second trip they climbed Mount Zomba and visited Lake Shirwa, now Lake Chilwa, which has no outlet and explored the highlands until early May. They then took the Ma Robert down to the delta to see if any relief supplies had been left. As none arrived they returned to Tete on 23 June and Thornton was dismissed a few days later.

Baines’ relationship with the Livingstone’s was deteriorating, but he was left in charge of stores at Tete whilst everyone else left on 11 July for the delta. After collecting stores they returned to the Shire Highlands until October; with the river levels low Kirk and Rae came overland to Tete where Kirk’s first task was to check if Baines had stolen any stores – his report was inconclusive.

Baines, Kirk and Rae hired canoes and rendezvoused with the Livingstone’s at the delta and so in November 1859 all the Zambezi Expedition members were at the coast awaiting re-supply and to learn if the British Government would approve an extension beyond the initial two years. Supplies were collected and members returned to Tete in early 1860 except for Baines who was dismissed and sent to Cape Town on HMS Lynx. Baines dismissal is discussed below.

Only Kirk, Rae, David and Charles Livingstone now remained on the expedition.

April 1860 — January 1861 - Expedition travels inland and returns after the canoes overturn and sickness

From April 1860 the Expedition members travelled with the Makololo assistants Livingstone had left at Tete at the end of his first expedition in 1856 back to Sekeletu and the Victoria Falls. This trip confirmed once and for all that the Zambezi river was un-navigable. On the way back some of the canoes overturned in the upper rapids of Cahora Bassa and Kirk lost many of his notes and specimens – they also suffered the discomforts of fatigue and hunger. Kirk intended to return home in 1861, but at Livingstone's request he remained on the expedition.

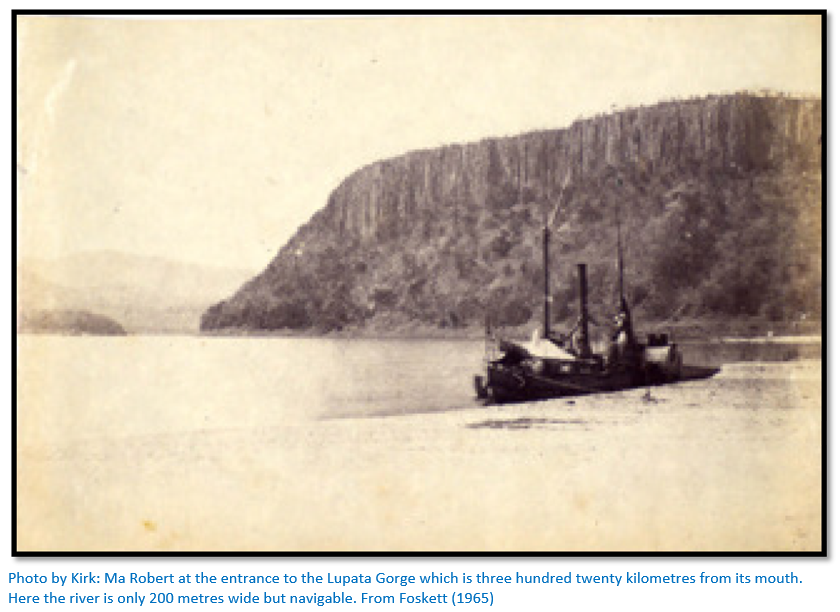

Having reached their base camp at Tete they set out for the coast in January 1861; the Ma Robert sank in the sands near Cheba, upstream of Sena, on 21 December as a result of her badly corroded hull and the journey was completed to the coast by canoe.

February 1861 — May 1861: Rovuma river impassable, illness on the Shire

At the coast a new paddle steamer, HMS Pioneer waited to replace the Ma Robert. She had been towed by HMS Lyra and accompanied by HMS Sidon with the first missionaries of the Universities' Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) and also the botanist Dr Charles Meller would join the expedition.

However the Shire river proved too shallow for both the Ma Robert and the Pioneer; the Portuguese used large locally-built canoes with Chikunda crews, but the thought of the UVMA having to rely on the Portuguese and their slaves was too difficult to contemplate. This despite the fact that the Zambezi Expedition had been completely reliant on Portuguese support in the previous three years!

Livingstone suggested using the Rovuma river which was outside Portuguese control (now the border between Tanzania and Mozambique) and which was believed to flow from Lake Malawi. This information was incorrect; one of the two major tributaries rises in the high plateau to the east of the lake.

However they were foiled by the shallow waters once again and by April, the expedition had only managed to travel thirty miles up the Rovuma River because the paddle wheels were continually fouled by objects in the river, including the bodies thrown in the river by slave traders. They turned back and returned to the Zambezi delta with most members suffering from malaria.

May 1861 — November 1861 - Kirk and Livingstone reach Lake Malawi

Between May and June 1861 Bishop MacKenzie and the UCMA were taken up the Zambezi and then the Shire river to Magomero in the Shire Highlands to establish a mission station. Water levels were low and the Pioneer frequently grounded on shoals for days. Yao and Chikunda slave raiders were causing a considerable disturbance in the region and crops had not been planted resulting in famine.

David and Charles Livingstone and Kirk left the UCMA to explore Lake Malawi in a four-oared rowing boat from August to November. However their gig could not handle the high waves caused by gales on the lake, they were robbed and often short of food. Their failure to explore the northernmost extent and circumnavigate the lake was considered at the time the greatest failure of the expedition.

Clearly this is connected with the mystery of the source of the Nile. Burton insisted the Nile rose from Lake Tanganyika, Speke that it was Lake Victoria; but if a large river flowed into Lake Malawi from Lake Tanganyika then Speke argued that the lake could not support two rivers.[iii] On 8 November they begin the journey back to the coast via the Shire River but were trapped by shallow water for a month and only the onset of the rains and rising water enabled them to reach the Zambezi delta on 11 January 1862.

January – March 1862; Supplies, the Lady Nyassa and Mary Livingstone arrive.

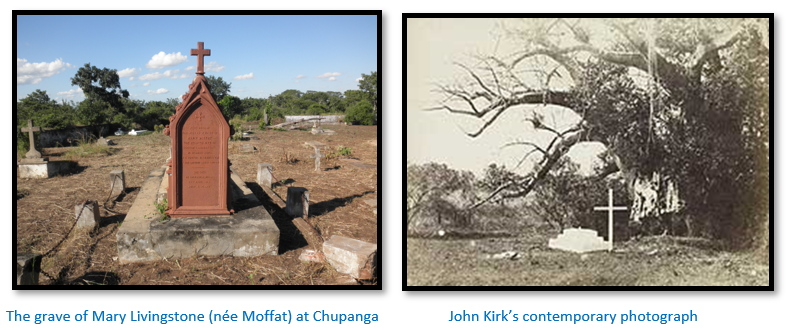

At the delta they met the HMS Gorgon and HMS Hetty Ellen with more missionaries, Mary Livingstone – Davis’s wife and James Stewart, a Scots missionary investigating the possibility of opening a cotton-producing industrial mission in the Shire Highlands. There were serious setbacks to the UCMA mission with several members including Bishop MacKenzie dying of malaria.

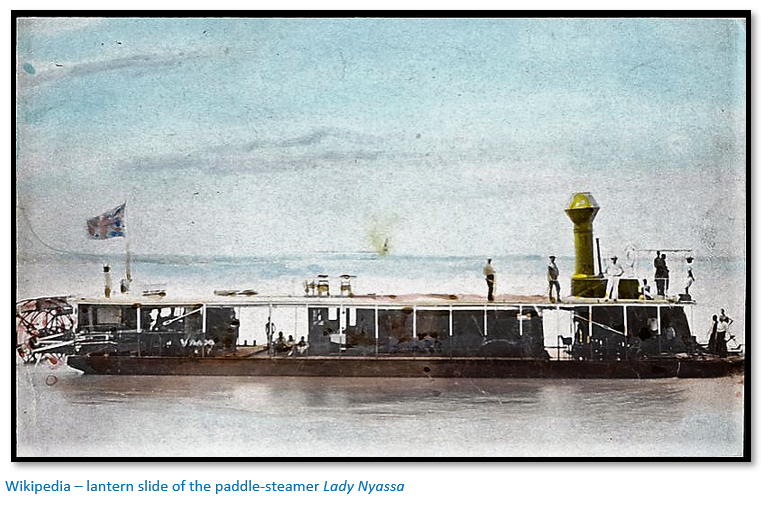

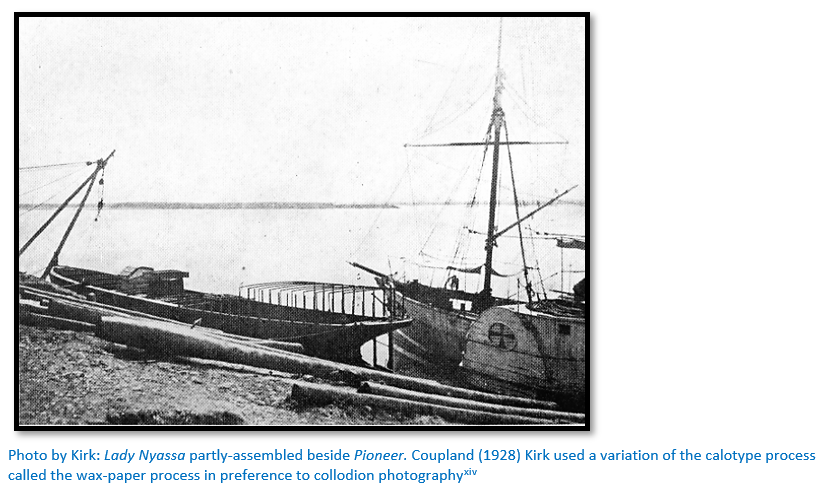

Another paddle steamer, the Lady Nyassa especially designed to sail on Lake Malawi arrived in pieces. The plan was to construct her on the lake and use her to support the missions carrying out work in the cotton trade and anti-slavery activities. David Livingstone had financed the Lady Nyassa himself from the sales of his book Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.

April — November 1862 : Mary Livingstone dies, problems with the Lady Nyassa, another fruitless journey up the Rovuma river

Mary Livingstone joined the expedition leaving her five remaining children in Britain. Already prone to illness and suffering from alcoholism brought about by her husband’s frequent absences, she died of malaria on 27 April 1862 after less than four months. Livingstone was devastated.[iv]

In April the Zambezi was too low for the Pioneer to carry the pieces of the Lady Nyassa to the cataracts of the Shire for portage around them, so she was assembled at Chupanga without her boilers so that she could be towed upriver, disassembled, carried fifty kilometres around the cataracts and re-assembled on the Shire to steam onto Lake Malawi; this was a huge task for George Rae with the minimum of equipment on the banks of the Zambezi river.

Whilst this took place Livingstone took Kirk and the Pioneer back to the Rovuma river leaving on 6 August and returning on 23 November for another attempt at reaching Lake Malawi– once again the river proved unnavigable.

December 1862 — December 1863; Livingstone unable to leave in May; UCMA mission leaves in December

In January the Lady Nyassa was towed with much difficulty by the Pioneer to the cataracts on the Shire river. News from the UCMA mission at Magomero was bad as food was desperately short. This was when Richard Thornton undertook his overland mission to Sena for supplies and died on his return in April. Livingstone decided to return to Britain to appeal to the Government for assistance, but once again the Shire was too low for travelling. Until the rains resumed at the end of the year he decided to explore west of Lake Malawi and observe the extent of the slave trade.

UCMA operations ceased despite the arrival of Bishop Tozer in June 1863. The mission had moved to Mount Moramballa to escape the malaria at Magomero, but conditions did not improve and in December the UCMA mission left for Zanzibar.

January 1864 – July 1864: Expedition withdrawal notice is sent. Kirk, Charles Livingstone and crew depart for Britain

David Livingstone left the Zambezi in January taking the Pioneer and Lady Nyassa to Zanzibar.

In April he took the Lady Nyassa to Bombay, a seven-week voyage, to sell her; in May, Kirk, Charles Livingstone and crew members left for Britain, although David Livingstone only learned of their departure when he arrived in London in July. The Zambezi expedition has ended.

The Zambezi Expedition was regarded as a failure in many newspapers of the time; Livingstone experienced great difficulty in raising funds for further exploration in Africa. The major positives to come out of the Zambezi expedition were the large quantities of natural history specimens - plants, birds, mammals, reptiles and fish collected on this expedition by John Kirk, Charles Meller and Richard Thornton, the scientists appointed to work under Livingstone. In the years following many lists and new species were published in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London and many of these specimens are now in the Natural History Museum.

The Zambezi expedition with Livingstone as leader is a disaster

The Oxford Dictionary of Biography calls it an unhappy expedition, but this is a gross understatement.[vi] In contrast to his Australian experience, the Zambezi expedition was to prove disastrous for Baines. Livingstone was the most famous Victorian explorer of his time and his name attracted funds and publicity and therefore his image had to be protected at all costs and his reputation supported.

The Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambezi and its Tributaries and of the Discovery of Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864 is based chiefly on the journals of Charles and David Livingstone and is mostly based on two periods totalling eleven months of the six years. The periods covered in detail are the journey from Tete to Sekeletu and back in 1860 and David Livingstone’s exploration west of Lake Malawi in 1863, which highlights the slave trade. Thomas Baines is not credited with his paintings which enhance the book.[vii]

It is valid question to ask: ‘how suitable was David Livingstone as the choice for expedition leader?’ when all his previous experience had been as “a lone wandering apostle of the London Missionary Society.”[viii] Dritsas attributes this to David Livingstone being in 1856-7 the acknowledged expert on southern tropical Africa and its most famous explorer.

Livingstone’s conflicts with his team

First to go was Livingstone's second-in-command, Commander Norman Bernard Bedingfield of the Royal Navy. Livingstone had met Bedingfield in 1854 at Luanda, Angola, where Bedingfield was in command of HMS Pluto, a steam gun vessel.[ix] They had furious clashes; Livingstone deliberately wrote him out of his own Narritive on the expedition and there is not a single mention of Bedingfield in that official account.

Dour and uncommunicative, often petty and vindictive, David Livingstone expected his men to share his own super-human powers of endurance and displayed an un-Christian lack of sympathy whenever they fell ill. Conversely, he was obsessed with his bowel movements, which dictated his moods. He could not bear anyone to question his authority yet could also be dangerously indecisive. “I can come to no other conclusion than that Dr Livingstone is out of his mind and a most unsafe leader” wrote the expedition’s physician, John Kirk, in despair.[x]

In reality Livingstone was a difficult man to work with, beset with anxieties and insecurities, with poor leadership skills and unable to communicate properly at a personal level.

The engineer George Rae felt the brunt of Livingstone’s wrath for the inadequacies and short-comings of the Ma Robert, described below. Although the two men were at loggerheads much of the time Rae was a fellow Glaswegian and this gave Rae an advantage in his dealings with Livingstone as the other relationships around them turned sour. It was Rae whom Livingstone relied on and trusted to take on the responsibility for building Mary Livingstone’s coffin after her death at Chupanga.

Rae was also accused of being an incurable gossip who was the source of the scandal suggesting that Mary Livingstone and the Reverend James Stewart had an illicit sexual affair after he reported seeing Stewart entering Mary’s cabin at night on the brig Hetty Ellen which had brought them out to join the Expedition at the Zambezi delta.[xi]

Then Livingstone himself wrote; “Rae has behaved with great duplicity, accusing Baines of having stolen his goods, then giving him a certificate that he had no reason to believe he had stolen any public property. I shall use him but be wary of trusting to him in the least degree.”

Charles Livingstone the source of negative whispers about Thomas Baines and Richard Thornton

Charles Livingstone, David’s brother, took his role as “moral agent” to the expedition extremely seriously and it only needed a minor slip-up in what he considered to be proper Christian behaviour for the men to get on his wrong side. Like David, he was racially arrogant towards the Portuguese at Tete, thinking them immoral and degenerate, so when Baines and Thornton displayed friendliness towards the officials at Tete, Charles thought the worst of them. David should have overruled this malicious gossip but failed to do so.

Dritsas considers Charles Livingstone as uniquely unqualified for service on the Expedition. He had trained as a minister but had neither scientific qualifications nor exploration experience and had never been outside Britain or the United States.[xii]

Wallis states that Baines natural history specimens “were denounced, he does not say by whom [most likely Charles Livingstone] as trash, lumber, stinking things and thrown overboard at the first opportunity” … “and he became tired of collecting. He felt he was looked upon more as a storekeeper and handyman than as an artist and there was no disposition to admit him to the liberal side of the expedition’s work.” This was in relation to a unique fish named shynyessi that Kirk obtained from a fisherman and tried to preserve which delivered electric shocks.

Baines dismissal

Baines was unjustly accused by Charles Livingstone of petty pilfering after apparently using spare pieces of canvas to paint pictures as presents for the Portuguese officials who had cared for him whilst he was prostrated with malaria at Tete and of carousing with the Portuguese at various trading stations along the Zambezi. He was sent home in disgrace (not the only one to suffer this fate), and not given the chance to defend himself publicly. Most of his possessions were left behind in Tete, and he never again saw most of his paintings although they were exhibited in London and Dublin and his manuscript map of the river kept by the Royal Geographical Society.

Baines came to the Expedition with recommendations from William Hooker and Sir Roderick Murchison; his exploration experience being second only to Livingstone. Hooker said he was more than capable of commanding part of the Expedition: “If Livingstone should find it necessary to go in another direction when in the interior.” He was an obvious choice being an experienced explorer and proven fieldworker.[i]

Baines had involved himself in every aspect of the Expedition, including woodworking and boat building, but suffered recurring bouts of malaria - as did most of the expedition members. The crunch came when he was accused by Charles Livingstone of being free and easy with the stores, of “skylarking”, ruining a whale boat and wasting his “time and materials in painting Portuguese portraits”.

In a feverish state, Baines responded to this accusation by Charles with some no doubt ill-chosen words that were interpreted as a confession. Baines letter of dismissal from David Livingstone has all the hallmarks of his brother Charles and is fully reproduced in all its sniping officiousness in the biography and makes for sad reading. Like Bedingfield, Baines was written out of the official Journal published by the Livingstone brothers, although his illustrations were included without his approval or authorization.

Clearly Livingstone’s secretive, self-righteous, and moody nature, and his inability to tolerate criticism made him the wrong choice as leader of an expedition.[ii] Baines innocence or guilt to the charge of theft can never be satisfactorily judged because he was never given a fair hearing.[iii]

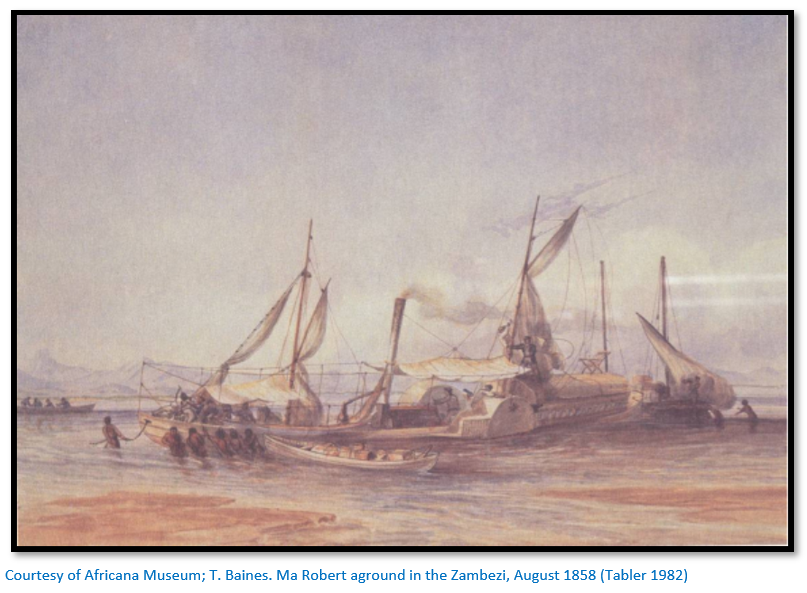

The Ma Robert proved an unsuitable vessel for the Zambezi river

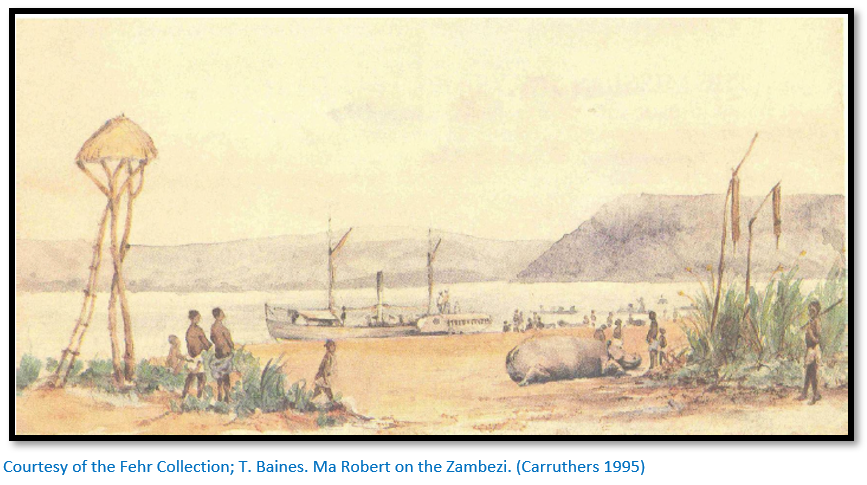

The steam paddle wheeler was built at the Birkenhead yard of Macgregor Laird and named Ma Robert, after Livingstone’s wife Mary, in the traditional African fashion of Ma for mother and Robert her eldest child.

Apart from the Zambezi river further exploration was required up the Rovuma (Ruvuma) and Shire rivers and a reliable steam vessel and the men to operate it was essential for the success of the expedition as the vessel allowed the expedition to carry more equipment than could easily be transported by land . However the Ma Robert’s boiler feed pipes was constantly choked with wood ash with the result that her cylinders and boilers kept breaking down.

Several tons of hardwood was required each day just to get up steam. Instead of employing men to stockpile wood ahead of the vessel they would be tied up on the banks of the Zambesi whilst local natives were employed to chop down wood. Chopping and hauling wood to the vessel took up more time than cruising, often two days at a time to chop down trees and saw them up into boiler-sized pieces. Local natives employed were inexperienced and did not enjoy stoking the boiler; even Livingstone is known to have beaten individuals of the native crew.[iv]

Kirk used these stops for “wooding” to “botanise” and make short collecting excursions; the fact these stops were not always suitable for collecting was secondary; collecting fuel was the primary concern. Kirk wrote to Hooker: “As far as I am concerned I may say that the expedition having turned out offering very few opportunities for botany and being heavy work simply transporting the gear from place to place I feel it rather a waste of time and shall probably soon find myself home” – however he stayed on from a sense of duty.[v]

In addition, the Ma Robert was unable to negotiate the cataracts on the Shire River as her engine was not sufficiently powerful to push her against the current and this forced Livingstone to trek overland to Lake Malawi. Another slip-up was to ignore the seasonal rise and fall of the river level of the Zambezi river and often there was insufficient water to float the vessel when fully loaded with people and equipment plus the massive quantity of wood fuel. The final straw was when the thin hull started to disintegrate and the holes had to be plugged with clay. "Asthmatic" as Ma Robert came to be known finally fell apart completely and sank into the sands of the Zambezi river in December 1860.

The Zambezi river was not the river that Livingstone had claimed

The shallow waters and shoals in the Zambezi and Shire rivers during the long dry season were an unexpected hazard to the Expedition members and caused lengthy delays. The shipbuilders and Admiralty had been concerned about the accuracy of Livingstone’s untrained observations of the likely depth of the Zambezi river which were made without instruments.

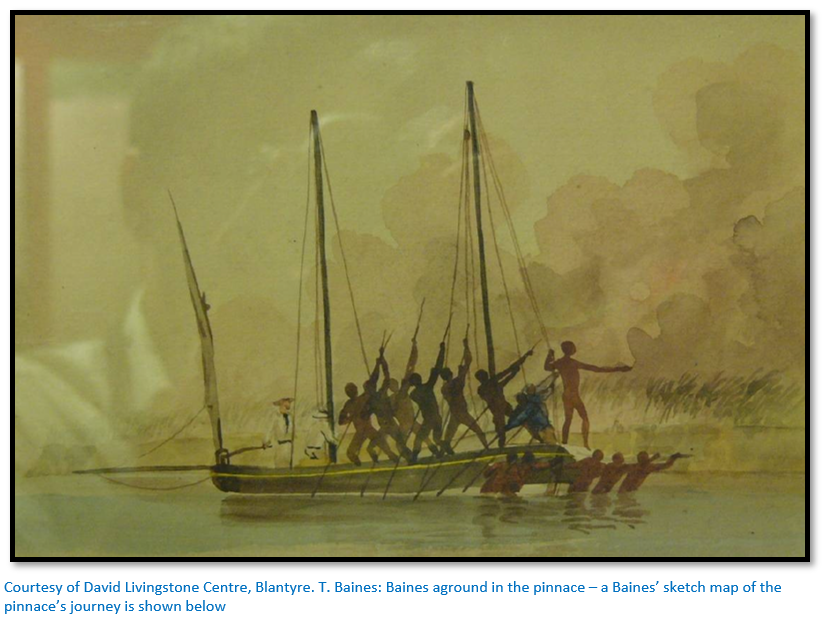

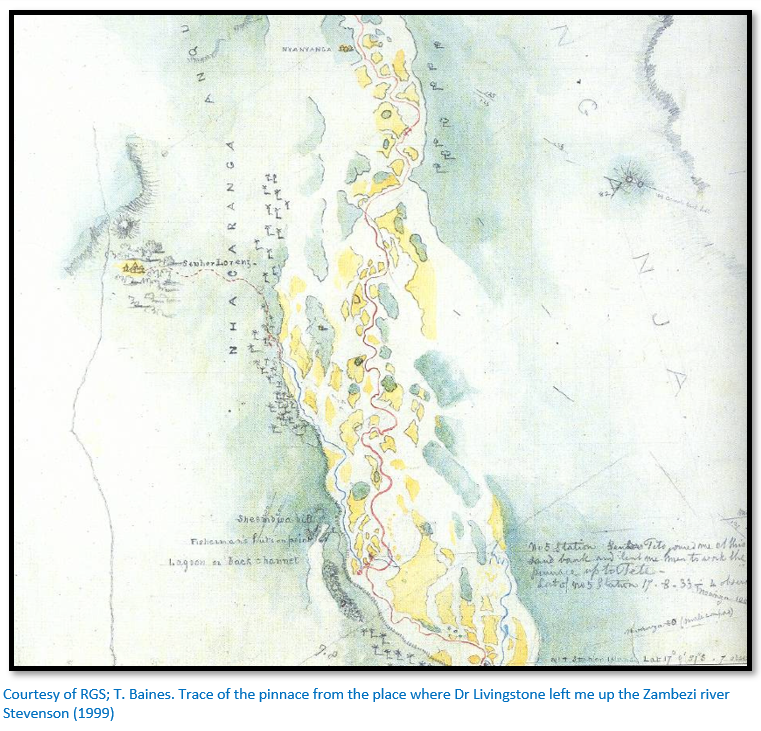

The Expedition were surprised to learn from Senor Vienna, the prazo-holder at Chupanga, that no channel to Tete existed in the dry season. Baines’ chart below shows the torturous course upriver that the pinnace took.

Kirk called the many days spent winching and hauling over shoals as “land transport.” After six months on the Zambezi Baines referred to it as “the broad labyrinth of shoals called by courtesy a river.”[vi] Extremely shallow in the dry season, the river’s channel meandered wildly as Baines’ watercolour above shows. The repeated failures of the steam paddle-wheelers led to widespread depression amongst the members of the Expedition and to the questioning of their leader.

Livingstone’s next Expedition

Despite his leadership failures, Livingstone was asked by The Royal Geographical Society in 1866 to lead an expedition to find the source of the Nile. Leaving the island of Zanzibar with a party of 35 soldiers, porters and freed slaves, but no Europeans, Livingstone again seemed unable to exert authority over his men and they soon they began deserting him taking with them vital supplies. On their return to Zanzibar they told the authorities that Livingstone had been killed by hostile tribes.

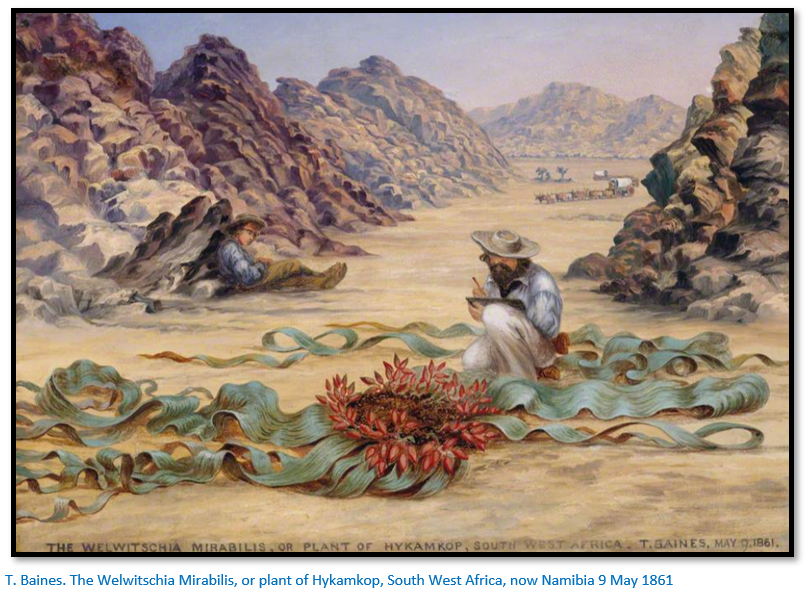

Chapman and Baines Namibia to Victoria Falls 1861 – 1862 Expedition

Baines returned to South Africa after this bad episode and from 1861 to 1862 he and James Chapman undertook an expedition to South West Africa, now Namibia and were amongst the first white men to view Victoria Falls on 23 July 1862. Chapman's Travels in the Interior of South Africa (1868) and Baines' Explorations in South-West Africa (1864) provide a rare account of different perspectives on the same trip. Baines made a complete route survey having been taught how to use surveying and astronomical instruments by Sir Thomas Maclear, astronomer royal at the Cape.[vii] [See the article The Victoria Falls Zambezi River sketched on the spot by Thomas Baines F.R.G.S under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

His paintings of the Victoria Falls (The Victoria Falls, Zambezi River was published by Day & Son) date from this time and are immense contributions to the artistic heritage of Africa, as are many of his other depictions of landscape, botany, zoology and people of the region some of which were published as coloured lithographs in 1862. The Victoria Falls, Zambezi River was published by Day in London 1865. In addition, the affair which had resulted in his dismissal from the Zambezi expedition still troubled Baines and he hoped to meet Livingstone to clear his name, but he arrived too late - Livingstone had already left the area.

Following their arduous return Baines stayed with Charles John Andersson in central Namibia and later painted the bird studies for Andersson's Birds of Damaraland and the Adjacent Countries, published at London in 1872.

An interlude in England

On his return from the Victoria Falls expedition Baines worked for a time at the Royal Geographical Society’s rooms in Whitehall Place lecturing on his African travels and illustrating his talks with magic-lantern slides apparently waiting an opportunity to return to Africa.

Gold exploration in Botswana and Zimbabwe

In 1868 Baines took charge of a prospecting company, the South African Goldfields Exploration Company and travelled a number of times from Durban to the Tati goldfields near Francistown in Botswana and in 1869 led one of the first gold prospecting expeditions to Hartley Hills near Chegutu in Zimbabwe. In 1870 Baines was granted a concession to explore for gold between the Gweru and Manyame rivers by Lobengula leader of the amaNdebele nation, although the South African Goldfields Exploration Company had insufficient finances to take advantage of this project. He mapped and wrote a useful description of the route from Pretoria to the Tati goldfields.

In 1873 he was awarded a testimonial gold watch by the Royal Geographical Society and in the same year visited the Injembe district of Natal to investigate gold deposits and attended King Cetshwayo’s coronation. He was busy writing an account of his expeditions when he fell ill with dysentery and died in Durban on 8 May 1875 at the age of 54 and is buried in West Street Cemetery.

Obituary

Sir Henry Rawlinson, president of the Royal Geographical Society, in his annual address of 1876, remarked that: “few men were so well endowed…for successful African travel, and perhaps none possessed greater courage and perseverance, or more untiring industry than Baines.” He never married, but his pleasant manner and faithful nature secured him many friends. He was a man of many talents but is primarily remembered as an artist. He left many thousands of sketches, watercolours and oil paintings and made a huge contribution to cartography which give a unique insight into colonial life in southern Africa and Australia. Many of his pictures are held by the National Library of Australia, National Archives of Zimbabwe, National Maritime Museum, Brenthurst Library, the Albany Museum, the Africana Museum, the Royal Geographical Socoiety and Cape Town Castle. Around 400 oil paintings are known to exist, and many more watercolours and sketches.

The Thomas Baines Nature Reserve near Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape of South Africa was named after him and he deserves to be better known for his passion for wild life and the natural landscape, for his perceptiveness, good nature and tolerance in his dealings with his fellow travellers, people of other races and nationalities.

Baines' most loyal promoter was his mother who, until her death in 1870, displayed his canvases in her sitting-room window in King's Lynn and in organised many public exhibition of his work. In 1851 she sent two parcels of her son's Eastern Cape pictures to Queen Victoria and organised the printing of most of his publications.

Renaissance man

Helen Luckett wrote on the centenary of his death: “... that he probably approached the ideal of Renaissance Man more nearly than anyone in Africa at the time. Besides being a proficient handyman, able to shoe a horse, mend a wagon wheel, or repair a rifle, he was an accomplished astronomer, navigator and cartographer, and a very competent botanist, entomologist (several plants and one insect were named after him following their discoveries) and he possessed a most intelligent and enquiring mind.”[viii]

References

T. Baines. Exploration in South-West Africa: being an account of a journey in the years 1861 and 1862 from Walvisch Bay, on the Western Coast to Lake Ngami and the Victoria Falls. London, green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1864

T. Baines. The gold regions of south eastern Africa. London: Edward Stanford, 1877

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi, Nelson 1965

L.S. Dritsas. The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64; African Nature in the British Scientific Metropolis. University of Edinburgh, 2005

Dustyheaps.blogspot.com

R. Foskett. The Zambezi Doctors; Dr Livingstone’s letters to John Kirk, 1858-63. Oliver and Boyd, 1965

https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Geoscientist/Archive/August-2011/Mr-Thornton-I-presume: Geoscientist 21.07 August 2011

H. Luckett. Thomas Baines, 1820-1875. The Geographical Journal Vol 141, No 2 July 1975

M. Stevenson. An Artist in the Service of Science in Southern Africa. Christie’s, London 1999

J.P.R. Wallis (ed.) The northern goldfields diaries of Thomas Baines. London: Chatto & Windus, 1946

J.P.R. Wallis. Thomas Baines, his life and explorations in South Africa, Rhodesia and Australia, 1820 - 1875. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema, 1976

J.P.R. Wallis. Thomas Baines of Kings Lynn published in 1941

Wikipedia / Wikimedia

William Barry Lord and Thomas Baines Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life, Travel and Exploration (1876)

[i] Ibid, P66

[ii] Wikipedia

[iii] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P25

[iv] Wikipedia

[v] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P101

[vi] Ibid, P94

[vii] Oxford Dictionary of Biography

[viii] Thomas Baines 1820-1875, P258

[i] Mr Thornton, I presume?

[ii] Ibid

[iii] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P150

[iv] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1298546/Dark-Dr-David-Livingstone-New-letter-casts-explorer-different-light.html

[v] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P106

[vi] Oxford Dictionary of Biography

[vii] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P23

[viii] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P49

[x] E. Wright, Ed Lost Explorers: Adventurers who Disappeared Off the Face of the Earth. Allen & Unwin, 2008

[xii] The Zambezi Expedition, 1858-64, P68

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: