Home >

Matabeleland North >

Inyati and the activities of the London Missionary Society in Matabeleland from 1859

Inyati and the activities of the London Missionary Society in Matabeleland from 1859

National Monument No.:

97

How to get here:

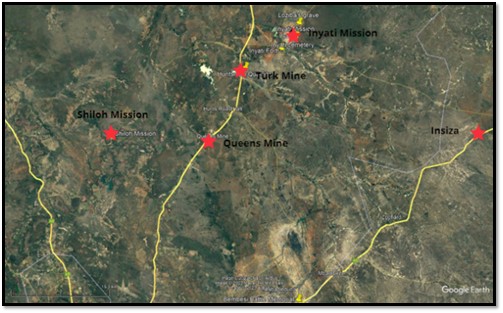

Take Robert Mugabe Way out of Bulawayo. From the turnoff to Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo International Airport to Queen's mine is 28km, Turk's mine is at 39km. Turnoff east to Inyati is at 44km, cross the Ingwingwisi river at 50km and turn left for Inyati mission at 52 km.

GPS for Inyati Church is 19° 40´ 16" S, 28° 52´ 29" E

Introduction

Most of what follows is taken from two sources. The first is the Reverend William Allan Elliott’s book Gold from the Quartz published in 1910. The book itself was awarded to Gladys Blowolb in 1911 by the London Missionary Society[i] (LMS) for collecting funds for their missionary ships in the South Seas and New Guinea, India and China and on Lake Tanganyika.

The second source is These Vessels…The Story of Inyati 1859-1959 by Iris Clinton. Much of the detail in this little book is from Rev Elliott’s Gold from the Quartz, but it does include useful information on LMS activities after 1910.

James Sibree’s book on the London Missionary Society lists 1,482 missionaries posted abroad between 1796 and 1923; 1,159 were men, 323 were women and 897 of the men were accompanied by their wives. It celebrates the great devotion so many people put into spreading the word of God around the world – many would suffer great hardship through disease and deprivation in the South Sea Islands, China, India and Africa.

Google Earth image of Insiza Mission, north of Bulawayo

Reverend William Allan Elliott

He was born on 19 May 1851 at Cheltenham and studied at New College, London. He was ordained on 20 June 1876 at the Congregational Chapel, Cheltenham and married Rosina Clapton the following day. They sailed from England on 23 August 1876 arriving at the LMS Mission at Inyati (present-day Inyathi) twelve months later.

They remained at Inyati until 9 June 1890 when because of the unrest and political disturbances in Matabeleland, caused by the Pioneer Column’s progress from Tuli to Mashonaland, they left for Palapye in present-day Botswana, and stayed with Rev James D. Hepburn,[ii] only returning in October.

In 1892 Mrs Elliott’s health began to fail and the couple in July left for England. On account of his wife’s health, Reverend Elliott felt unable to return to Matabeleland and his connection with the LMS ceased. In July 1895 he became Pastor of the Congregation Church at Frizinghall, near Bradford, Yorkshire and from 1914-22 that of Clifton Down, Bristol.

Robert Moffat (Mtjete) opens the way for the LMS in Matabeleland

In 1829 Robert Moffat[iii] guided two indunas sent by Mzilikazi to Kuruman back through territories hostile to the amaNdebele. Mzilikazi said to Moffat, “These are my servants whom I love. They are my eyes and ears and what you did for them you did to me.”[iv] Again in June 1835 they met when Moffat escorted a scientific expedition into the interior and so began a great friendship.[v]

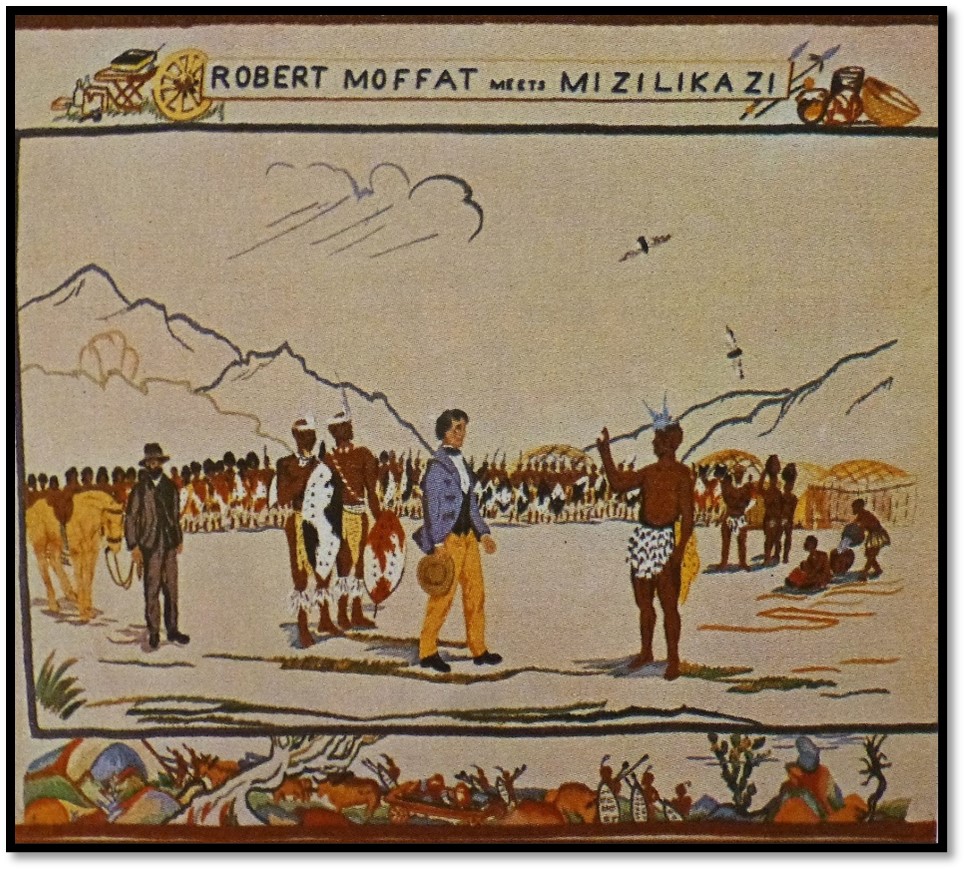

Rhodesian Tapestry, Embroidered by the Darwendale Women’s Institute:

Robert Moffat meets Mzilikazi

In 1854 Robert Moffat with Sam Edwards[vi] and James Chapman trekked to Shoshong where Chapman left for Lake Ngami and Moffat and Edwards met Mzilikazi at Matlokotloko where Moffat treated the king for gout and spent eleven weeks in Matabeleland. They then travelled to the Nata river taking supplies and mail for David Livingstone[vii] that were taken on to the Zambesi Valley by the king’s men.

In 1857 the directors of the London Missionary Society passed a motion, “that two new mission stations should be opened – the one among the Makololo, north of the Zambesi…and the other among the Matabele…”[viii] Moffat again travelled to Matabeleland and renewed his contact with Mzilikazi to prepare the way for the Matabele mission and again was given a warm welcome.

Kuruman Mission, once the most inland permanent mission, would become the logistical base for these new missions to the north.

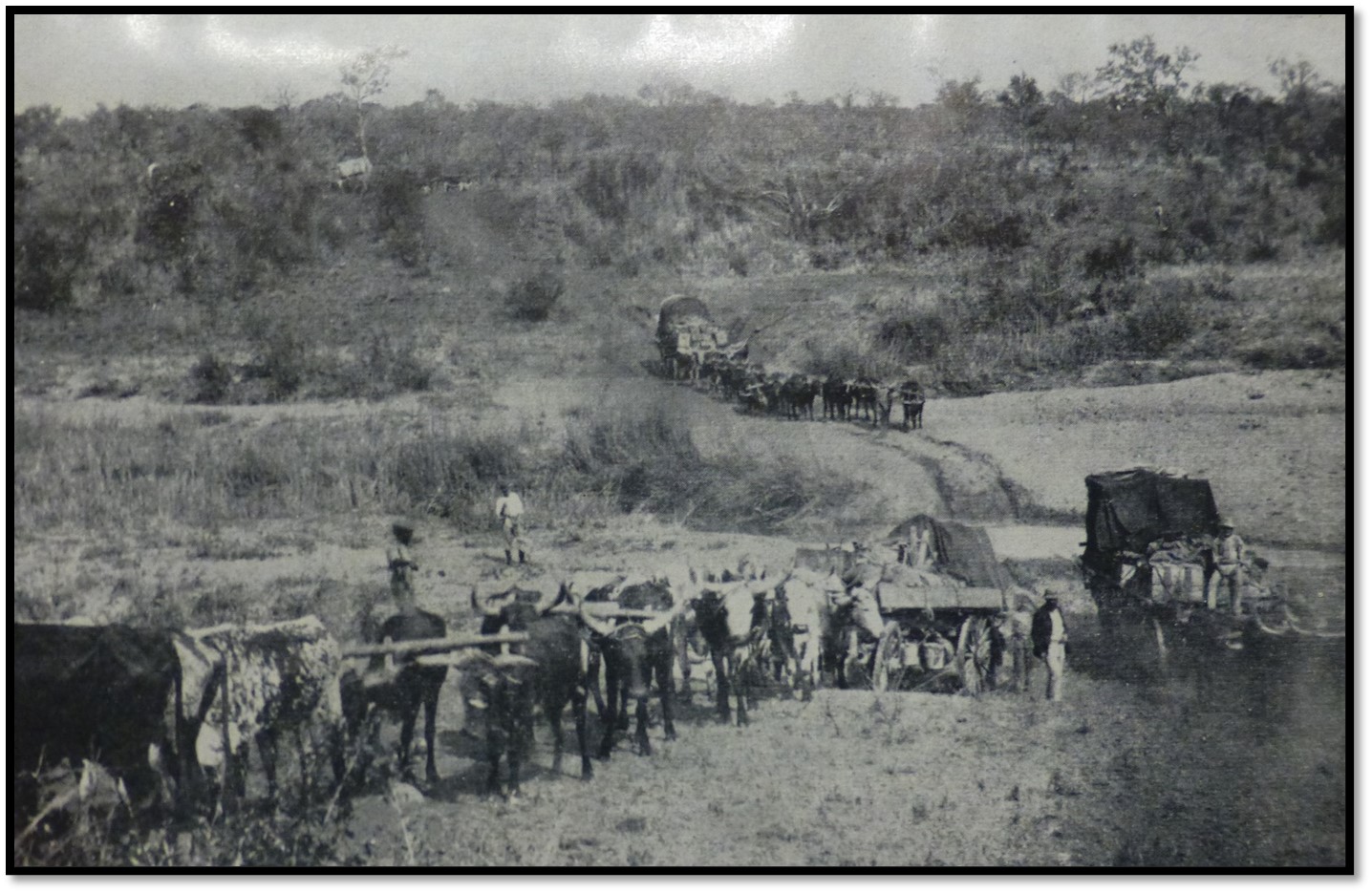

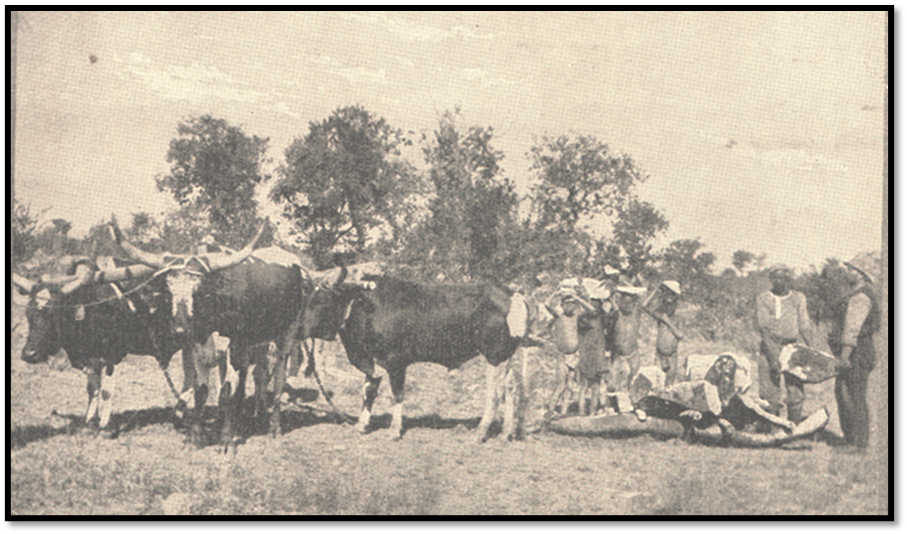

Ox-wagon crossing a shallow spruit

On 14 July 1859 three wagons left Kuruman with, John Moffat and his wife Emily,[ix] Thomas Morgan Thomas and his wife Anne,[x] eight Kuruman artisans and two girls carrying two years supply of stores. Robert Moffat and William Sykes left on 1 August and the party united at Bakwena.[xi] After a long and hard journey, frequently short of water, they reached the amaNdebele outposts and Mzilikazi, now in Matabeleland, sent a messenger to say, “The king longs exceedingly to look on the face of Mtjete again.” By 10 September they reached the western edge of the Matobo Hills at Makobi’s kraal and saw running once streams again, but halted because they heard that lung sickness had broken out and did not wish to spread it amongst the amaNdebele herds.

A messenger came and urged them to hasten on. Six days later, they were halted, Mzilikazi had sent his young warriors (Majakas) who inspanned themselves and pulled the wagons in relays, singing and chanting, to Mzilikazi’s royal cattle post at New Matlokotloko on the Bembesi river. Emily Moffat wrote, “I was surprised to see the eagerness and power of the men…the two sets of men had a race - it reminded me of the omnibus drivers vying with one another. We gained the advantage at first, and the lumber waggon, tortoise-like gained upon us afterwards. At any difficult place the men’s recourse was to sing very vigorously and then a mighty pull and on we went.”[xii]

The missionaries high expectations were soon dashed however, when Mzilikazi refused to discuss the possibility of a mission station, then after three weeks keeping them on tenterhooks, he inspanned his wagons and left them in solitude. Sykes kept the LMS directors informed, “We reached Moselkatse’s kraal on Friday the 28th of October 1859…His treatment of us till about a fortnight ago was peculiar. During the first three weeks we often saw him and generally made some effort for trading, but his unreasonable demands in nine cases out of 10, were an insuperable barrier in barter. He would ask twice, thrice or four times the price for different things which we required, that we could purchase those same things for at Kuruman, or from any other of the tribes lying between. My impression was, before long, that he designed to fleece us and send us about our business. Such was out getting on during the first three weeks.”

“On November 22nd, the King’s wagons were inspanned and away he led us to a town more than seven miles distant…During the next four weeks we were, to all intents and purposes, prisoners.” Their spirits fell just as the rains started leaving their camp a quagmire and messengers began to arrive from the king accusing them of being spies and demanding guns and ammunition from them.

Their spirits sank, although Moffat’s messages to the king were always dignified, as they were forbidden to move, or to hunt, when suddenly they were told the Inyati valley and its spring were for their use as a Mission station. Mzilikazi sent oxen and a guide, Monyebe,[xiii] although the two day journey, in the wet conditions, took a week’s travel, before they forded the Ingwingwisi stream and trekked to the head of the valley, the long low hill of Ndumba (bean) behind, that was reached on 26 December 1859.[xiv]

Monyebe said, “The king says ‘if the valley you see pleases you, it is, with the fountain, at your service. Choose where you wish to build and occupy as much land as you please. If you are satisfied, the king will be glad.’.”

Inyati Mission

Their arrival at Inyati was watched with interest. On the first Sunday Robert Moffat and Sykes went to the royal town of Emhlangeni, a short distance from the new Mission to ask Mzilikazi if the people might be collected for ‘the teaching.’ Permission was given and many came. Hymns were sung in Sechuana, the language at Kuruman Mission, and a sermon given.

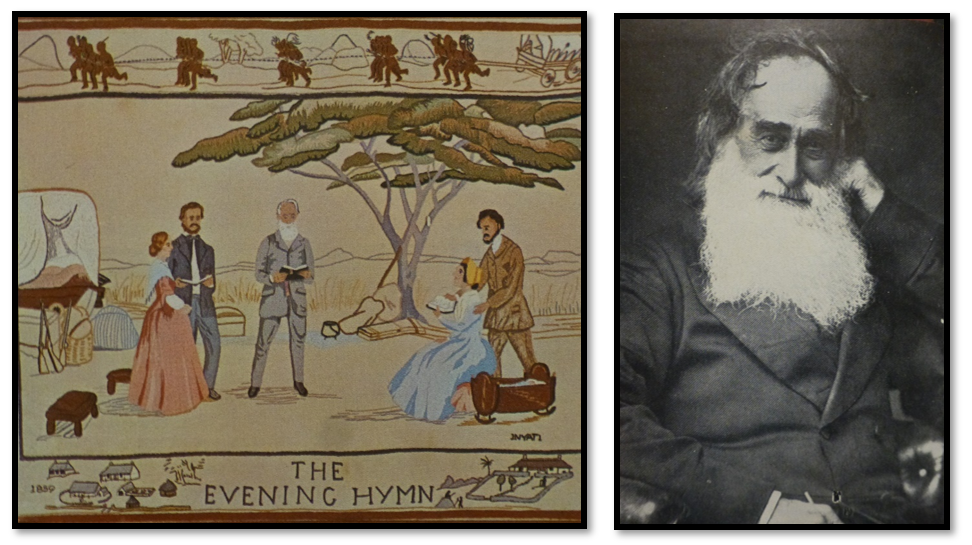

Rhodesian Tapestry, Embroidered by the Inyati Women’s Institute: Robert Moffat meets Mzilikazi

The panel depicts Robert Moffat (centre) John and Emily Moffat (left) and Rev and Mrs Thomas.

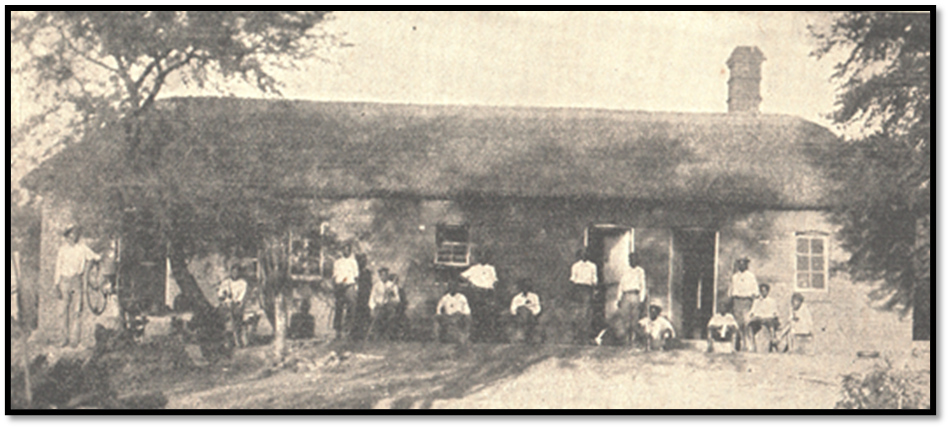

Then work began on constructing pole and dhaka huts for homes, a dam was built to hold the water of the spring and to supply a garden and kraals for sheep and goats and the oxen. Work was begun on a sawpit and a forge where the king brought his wagons and guns for repair. Fortunately, the missionaries had the help of skilled brick-makers and builders who had come from Kuruman with them.

On 15 April 1860, Livingstone Moffat was born to John and Emily Moffat, the first white child in the country.

Emily wrote to her father, “after Baby's birth, our native hut gave way, so we adjourned for the night to our wagon. I found that so unpleasant with baby that we moved our bed into our tent, and here we are.”

Moffat’s last service at Inyati was held on 17 June 1860; Mzilikazi had protested at his departure, but finally gave his assent. The king held Moffat’s hand and said, “Why should I continue looking on you? Go nicely, I will take care of the teachers.”[xv] They never met again, but both Mzilikazi and his son Lobengula kept the promise to look after the missionaries.

Their two-roomed houses were built near the spring, William Sykes’ house on the exact spot where Robert Moffat has stopped his wagon. Sun-dried bricks were made, the walls plastered within and lime-washed. Timber was cut for the roofs that were thatched. Windows were covered with calico and the floor made of clay, mixed with cattle dung.

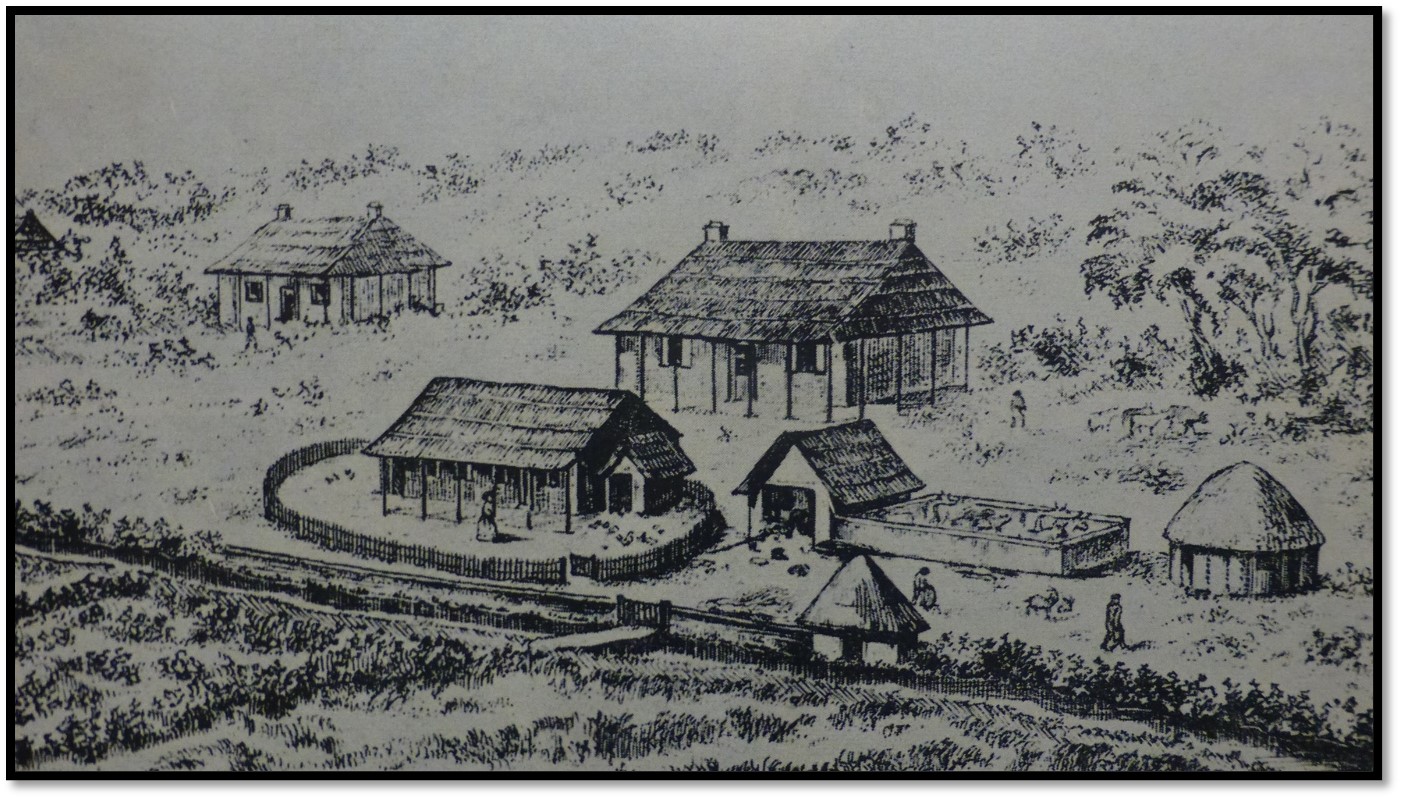

Sketch of Rev W.A. Elliott’s first house at Inyati in 1877 – typical of a missionary home with the kitchen on the left

One initial difficulty was insects – black and white ants that ate the wood timbers and burrowed into the thatch, rats, snakes, spiders and beetles. In time however the missionaries leaned to cope and conquer these inconveniences.

Local people exchanged labour for calico and beads, women made most of the clay used in brick-making and floors. Young men helped with the timbers and thatching.

Around the Mission station lay the huts and kraals and the gardens of the amaNdebele people. In the early days wildlife was often encountered. F.C. Selous, one of the most famous hunters, describes meeting Sykes at Inyati in 1872. “He (Sykes) told me that when he first came here in 1859, game of every kind abounded, that he had often been called by the natives to drive elephants out of their cornfields, that he constantly saw buffaloes and rhinoceroses going down to the river to drink in the afternoon and that lions roared nightly round his house, and frequently quenched their thirst in the little reedy pool not more than 200 yards from his doorstep.”

The missionary day was comprised of building, carpentry, tending the gardens or livestock, evangelical work, medical work, buying local provisions, teaching, training teachers, preparing sermons, writing letters – both the missionaries and their wives needed to be a jack-of-all-trades.

Thus began the first mission station in the country and the earliest European permanent settlement.

Missionaries usually lived very isolated lives

Rev Sykes left even before Robert Moffat to take back the men who had come from Kuruman with the wagons.[xvi] That left just Rev Thomas and John Moffat with their wives 650 miles (1,050 km) from the nearest missionary settlement at Kuruman. Elliott writes for those at Inyati, “There was a multitude of people, but no companionship; plenty of labour, but little help” and goes on to say, “The missionary was a mystery. Traders and hunters they could understand, but the missionary?”[xvii]

When the missionaries tried to tell the amaNdebele people of their homes across the water, one town (London) containing more inhabitants than all the people of Matabeleland, of wagons running without horses and oxen, of ships that held as many people as one of the amaNdebele towns, they were incredulous and believed the missionaries were lying.

Letters were the missionaries contact with the outside world and in the beginning they were brought monthly by runners, although they became more frequent with time. Also hunters and traders brought welcome news of the outside world. Henry ‘Old Baas’ Hartley, Thomas Leask, George ‘Elephant’ Phillips, Frederick Selous, George Woods were all welcomed in for food, conversation, games and music.

The threat of sickness was ever-present. In May 1862 Mrs Thomas and her two-month old baby girl became ill and then the child died followed three days later by her mother. Her loss in such a small community was very painful. They were buried in the Inyati cemetery, she was only twenty-two.

Rev William Sykes

William Sykes was born on 13 March 1829 at Mirfield, Yorkshire and was a grocery clerk before training with the LMS and was ordained in Aril 1858. He was initially extremely reserved and withdrawn as Mrs Sykes had died at Kuruman on 19 May 1859 worn out by the travelling across the Karoo. In 1860 he married Charlotte Kolbe, a daughter of a Rhenish missionary at the Cape Colony and they had four children. He immersed himself in languages, first Setswana and then Ndebele. In the future he would make many translations of hymns and prayers. He witnessed Lobengula’s coronation at Mhlanhlandlela on 22-24 January 1860 and he and Thomson helped the wounded after the battle of Zwangendaba on 5 June 1870. Sykes and Rev Hepburn influenced King Khama III to keep the Jesuits out of Bechuanaland in 1879 although he became friendly with them at Sacred Heart Mission at Old Bulawayo. Sykes stayed at Inyati until his death on 22 July 1887, his wife died in 1920.

William Sykes was the most influential missionary at Inyati and should be regarded as the prime mover for its existence and without him it probably would not exist today.[xviii]

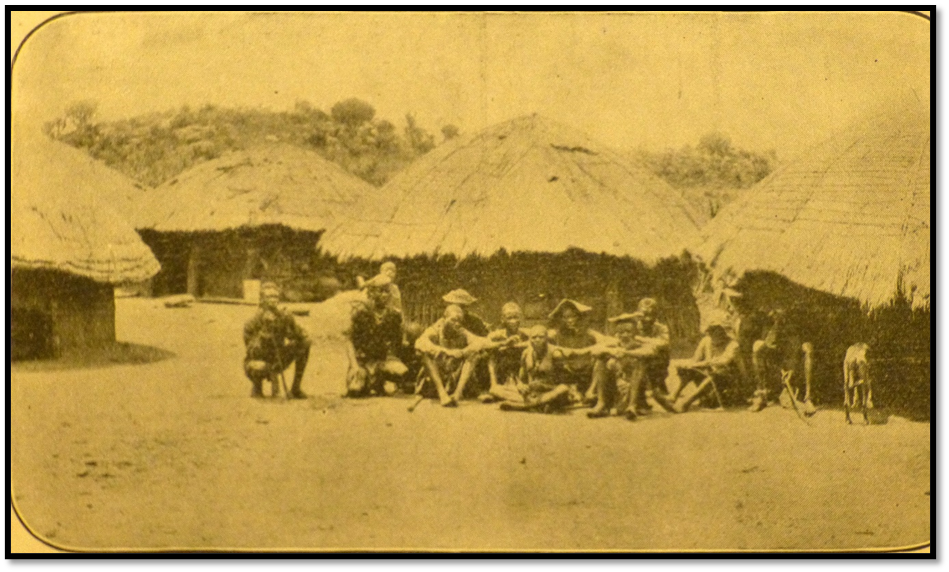

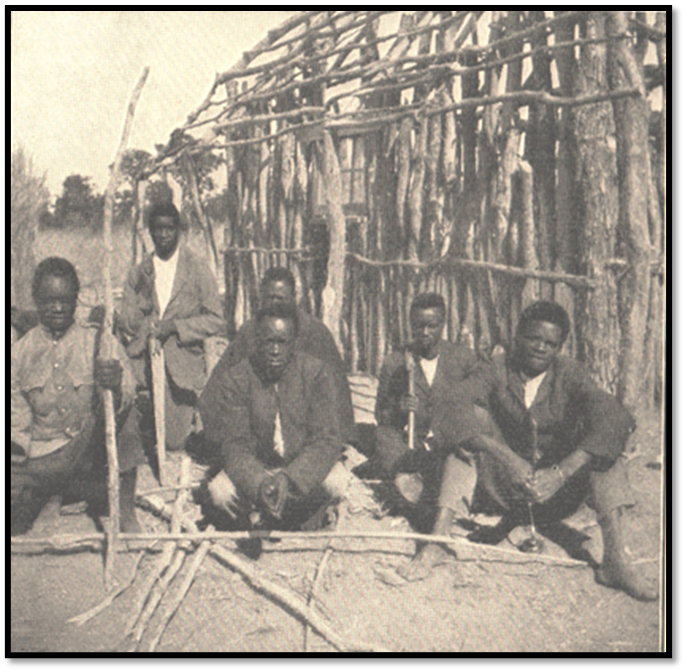

Inyati Mission station about 1860

Emhlangeni

About a mile from the Mission was the royal kraal of Emhlangeni, with its iNyati (Buffalo) regiment. The village was surrounded by two circular fences made of branches and thorns, perhaps 300-400 yards (275-366 metres) in diameter with about 100 feet (30 metres) between the fences and housed between six hundred and a thousand amaNdebele people.

Each family had its own compound, containing huts for the head of the family, one for each of the wives and others for the children and slaves (Maholi) plus one or more granaries, usually lifted above ground on poles. An open space in the centre was used as a public meeting place.

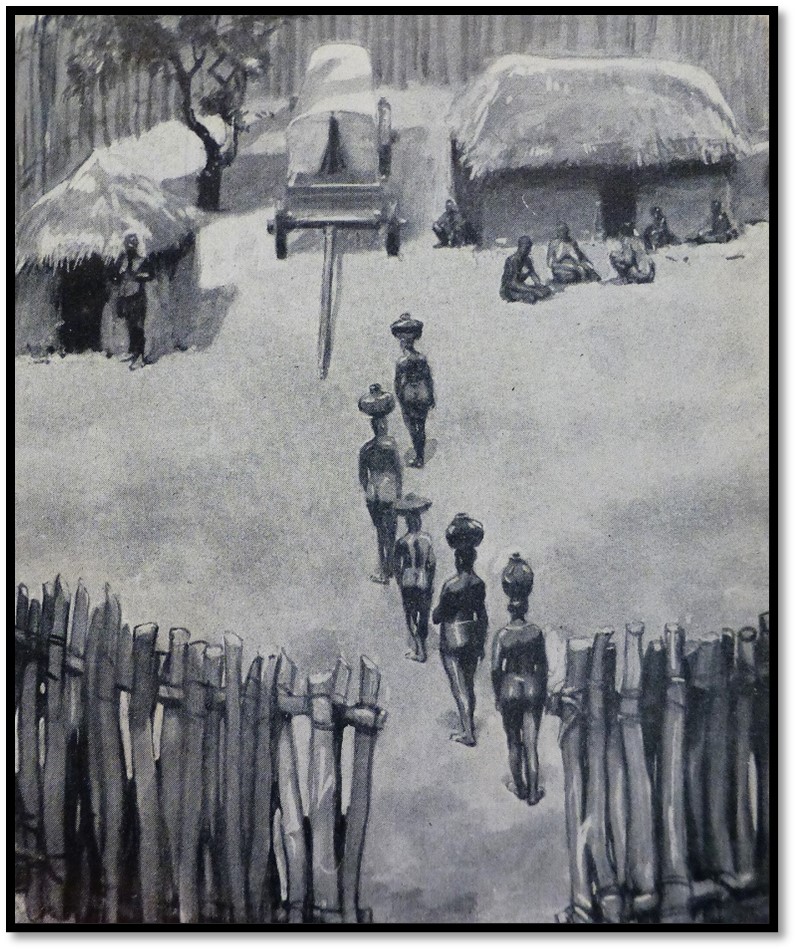

Rev W.A. Elliott: scene from an amaNdebele village

Mzilikazi moves away from the vicinity of Inyati before his death

On the 5th of October 1861, uLoziba, the King’s chief wife, died of rheumatic fever. Thomas wrote in his book, “It is the custom of the AmaNdebele tribe that when the great queen dies at a certain town, such town is forever deserted by her husband, who henceforth takes up his quarters at the town of the next great queen. ULoziba was buried in one of the cow pens, and honour which is only confirmed upon the most distinguished and great. Umzilikazi moved on from town to town, till at last he reached Umhlahlanhlela and the multitudes of people who used from all directions to come together to Inyati were seen there no more.”[xix]

The missionaries made frequent references to Mzilikazi’s failing health and he suffered from gout and could not put his feet to the ground. Rev Thomas who had a certain amount of medical skill was able at times to give him some relief, but on the 6 September 1868, he died at a village about fifty miles south from Inyati minority called Ingama.

During the Interregnum the amaNdebele search for Mzilikazi’s heir

The amaNdebele 1848 knew that Nkuluman had been appointed as Mzilikazi’s heir and according to their custom had been driven from home to wait in exile, his accession to power. For months the search went on under Ncumbata, the regent. But when it proved fruitless, Lobengula, a son of Mzilikazi by a Swazi princess was approached, and finally on 22 - 24th January 1860, his coronation took place as king at Mhlahlandhlela.

Lobengula was opposed by the Ingabha regiment who believed Nkuluman should be king. They refused all offers of peace and at last Lobengula’s patience was exhausted and his army joined in battle with them at Zwangendaba and won a victory. That evening, the mission station was crowded with wounded and next day Sykes and Thomson rode over to the battlefield and helped the wounded there.

Hope Fountain Mission

Rev Elliott writes that the under-manning of the mission imposed a great strain on the missionaries. “The conditions altogether were unspeakably depressing. The climate depressed, the loneliness depressed, the apathy of the people depressed, the non-success depressed, the insistent strain of working beyond strength depressed and the result was disastrous to the work.” To overcome these difficulties “demanded a small colony of, say, half-a-dozen families, whereas at times there was only one family, and occasionally one man. The thing was impossible.”[xx]

The solution seemed to be two stations, with two families at each station, but King Mzilikazi always refused permission. He was very friendly and faithfully stood by his promise to Robert Moffat, but he would not allow any more missionaries into Matabeleland. Many appeals to him were made over the years, but all were rebuffed. Rev Price was refused entry, Rev McKenzie was allowed to visit, but not teach, Rev Wookey visited but left and only in 1870 did the situation change with the new king.

Rev Sykes were alone at Inyati – poor health prevented John Moffat and his wife returning and John Boden Thomson arrived to replace them. Sykes and Thomson decided to approach King Lobengula and to their great surprise he replied, “where do you want to build? The country is before you, go and seek a place.” They could hardly believe their ears. It seemed too good to be true.

Lobengula agrees to a second mission station

An induna recommended a suitable place for a mission station and when examined, it seemed ideal being 3½ miles (5.6 km) miles from Old Bulawayo in a charming valley, with a beautiful spring of water, and with a large population. Henry Hartley and Thomas Baines were asked for their opinion and gave a positive verdict. The two missionaries went back to the king and were dumbfounded when he brusquely asked, “why have you been riding about my country?” You told us to look for a new station where Thomson could build; we have been doing so with the help of Baines and Hartley. I do not want any more missionaries; I have enough” said the king.

Monday saw the king at his wagon and Thomson brought up the subject again, with John Lee[xxi] acting as interpreter, in place of Sykes who had returned to Inyati. Many questions were asked. “Were missionaries of any use to the people?” The King and indunas seemed to be of the opinion that the country was better without them. “What is the message from God? How would the message benefit him and his people? What is the missionary society?” To these questions answers were given.

The King said, “I believe in God. I believe that he made all things just as he wants them to remain. I believe God made the Matabele just as he wished him to be; it is wrong for anyone to seek to alter them…God has left his people so long, I feel sure that he intends them to remain as they are.”[xxii]

The king said that Sykes and Thomas[xxiii] had been in Matabeleland for a long time and the people had not learned. Then he said he was tired and he wanted to take some time to think about it.

The king gave them no reply for a week and when Thomson told him that his supplies were low and he must go home, the king said, “I give your Society that valley for a mission station as long as they like, under me as king, and no trader is to build there.”[xxiv]

The missionaries were overjoyed and Thomson employed a white builder to build a pole and dhaka thatched house whilst he went to Kuruman to replenish supplies. Elliot says, “but the white man, after the manner of his type, took his ease, and the house was far from finished when family and stores were waiting for it. Under pressure of righteous indignation, the house was hurriedly finished and scamped. Of course the roof fell in. That white man was a bad lot.” The dhaka and thatch house lasted a year or two until replaced by brick.[xxv]

A dam had to be built before a garden could be made, the stock of spades and shovels ran out, and had to be borrowed. “Workers were up to their knees in mud and water for days together, and some of the natives proved themselves of the same type as that white man, but with greater excuse. They appeared to have thought it sufficient to start work about 11:00 am in the morning and to finish about 2:00 pm. This, with numerous intervals for snuffing, left little time for work.”

Neville Jones, My Friend Kumalo: the old mission station at Hope Fountain from a sketch by Fr Croonenberghs

The King had promised to visit Hope Fountain Mission and in July 1871, he came on horseback. He had a good look around, taking a fancy to some of Mrs Thomson’s fowls which were given to him. He was much taken by the brick house and ordered his own people to make bricks for himself. A month later he came again, accompanied by his sister, Njina (Mncengence or Nina) and 3 waggons and about 150 courtiers He outspanned at the front door of the house and took his food with the Thomson’s. Next morning he re-examined the brick house and stated he must have one like it at Old Bulawayo. He praised the garden, but showed the greatest interest in three little piglets, requesting some offspring in the future. Next day large numbers of amaNdebele came to greet their king and sang and danced before him.

Second LMS missionaries arrive in Matabeleland

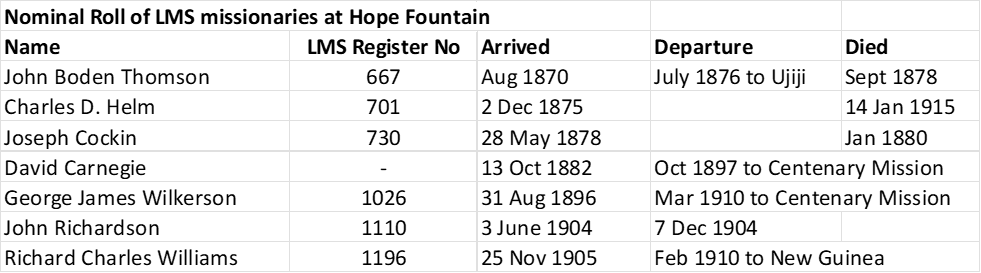

In 1875 Rev Charles Helm arrived at Hope Fountain to be followed in 1877 by Rev William Elliott, the author of one of the books used in this article, at Inyati Mission. Almost immediately Rev Thomson left Hope Fountain to establish a new Central African Mission, but within a few months was a victim to fever.

Mr Cockin arrived in 1878 at Hope Fountain, but he too fell victim to fever and died at Shoshong in February 1880. Only in 1882 when David Carnegie arrived did the “two mission families at each of the two mission stations” become an accomplished fact.

In January 1884 Thomas Morgan Thomas passed away. Rev Elliott does not name Thomas, just calls him, “Thomas Sykes first colleague in the pioneer work of the mission [Inyati] had passed away. He was a great worker and gathered a small company of disciples round him at Shiloh, most of whom fell away after his death.”

Rev Sykes died in July 1887 “after twenty-seven years of strenuous and almost thankless toil in the ‘hopeless’ Matabele field”[xxvi] and was buried at Inyati cemetery. His successor was Mr Bowen Rees who arrived in March 1888.

The same year saw the return of John Moffat, to the scene of his earlier life, but now as British Resident. Elliott writes, “English power was making itself felt at last in those remote regions and would ere long strike a mortal blow to the tyrannies and devilries of Matabele rule. A new era was dawning, soon to flood the land of darkness and death with the light of the gospel and of civilisation.”

Lobengula’s attitude is perplexing to the Missionaries

The ‘four missionaries, two stations” had been achieved, but the promise of the early years of Lobengula’s reign had disappeared, largely the missionaries thought, due to the influence of certain Basuto ‘doctors’ on the king and the continued annual raids for tribute and also to terrorise the tribes on their borders into submission.[xxvii]

David Carnegie refers to Hlegisana, Professor Roberts states he is the son of Bulali and that the Mzizi family were Lobengula’s ‘war doctors’ and exercised a malevolent influence over him. Carnegie writes in Among the Matabele, “it was the one found dream of Mr. Sykes life to try and win him [Lobengula] over to Christianity. But the arrival of Hlegisana from Hopetoun in Cape Colony, but a stop to all this. This coloured man professed to have powerful medicines, by means of which he could sharpen the spears of Lobengula's warriors and make them successful in war. He caused the chief to believe that the missionary was a man of peace, did not encourage war in any shape or form, and if he accepted his principles, he would never be a great king like unto his father whose death was compared to the falling of a mountain; besides, this would mean a new departure, and a serious one too, the throwing over the old habits and heathen customs of the tribe. Thus it became apparent that the king must choose between the army doctor and the missionary. It was evident he could not be a Christian chief and a heathen at one and the same time, and he decided to listen to the army doctor, and the missionary from that time sat outside the king’s hut and the army doctor inside with the king.”

Lobengula wrote to the Lieutenant-Governor of Natal Colony in 1874. “The King is glad to have teachers living in his country to teach his people. God’s word came to the white people first, and they received it readily; now it has come to the King and his people and they will follow behind the white people. The black people are very hard and unwilling to leave their own customs and to practise all the teachings of God’s word. White men listened readily, but the black people will not listen. They will come to God in the year appointed them. The king has given his teachers liberty to teach all his people God's word and has told him to listen to their teachers. He has advised them to send their children to be taught the white men's books. Some time ago he sent his own children to be taught and now one of them can read a little and the others are learning.”[xxviii]

The missionaries could not understand if this was just diplomatic posturing or the outcome of his good nature.

J.S. Moffat wrote in 1891, “An awful gloom hangs over this land. After twenty-two years’ absence, I have returned and spent four years at the Matebele court and the impression made on my mind is that so far as there is any change at all in these people, it is a change for the worse. The old Zulu strain, which had in it something of nobility, has been nearly weeded out by cruel murders till four-fifth of the nation are slaves, with all the meanness of their servile nature, and all the arrogance of their tyrants. If I look for any benignant influence traceable to the preaching of the Gospel, there is scarcely the glimmering of the tiniest star.”[xxix]

A young girl who became proficient at reading was accused of witchcraft and she and ger parents cast out. Rev Thomson found the girl and took her into his house and settled her parents with the king’s permission. She wrote a letter to the king and Thomson took the girl to the king to read her letter. When he heard it, he called his councillors. They exclaimed, “she is a white person” and the king added, “now I know that my people can learn, for I have seen what a little girl can do.”

After the 1893 annexation of Matabeleland

Mr and Mrs Rees were welcomed back to Inyati by those converts who still remained, the old mission houses had been burnt down, but were rebuilt and construction on a new church began with the cornerstone cut from the rock at Ntabazinduna. Two of the earliest converts, Makaza Nkala and Matambo Ndlovu led the construction efforts.[xxx]

The March 1896 Rebellion (Umvukela)

The Church was only just finished when the Matabele rose and many farmers, miners and traders were cruelly murdered,[xxxi] with the remaining whites hastily called into laager at Bulawayo. Rev and Mrs Rees encountered an impi at Elebeni and the young warriors (Majakas) were all for killing them, but their induna remembered how these missionaries had been befriended by Lobengula and ordered, “these vessels are not to be broken.”

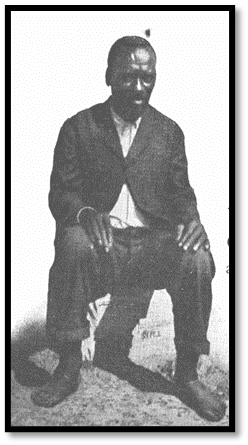

The young converts Makaza and Matambo were taken and bound, as they had been specially marked out for vengeance, in that they had left the ways of their fathers’ and gone over to the white men. Matombo's brother, Maqamula was in the impi that captured them and was allowed to set him free. But Makaza had no brother to intercede for him and was led out and stabbed to death.

Rev W.A. Elliott: Matambo Ndlovu as a boy

After six weeks Rev Rees was allowed to accompany a troop of horsemen back to Inyati – the remains of Assistant Native Commissioner A.M. Graham, Sub-Inspector Mark Handley MMP Troopers George Case and George Hurford, Leighton Huntley Corke ex-MMP were found and buried in the mission cemetery, as was Makaza Nkala.

Peace comes and a network of outstations is established

By 1896 Matambo and Zhisho were well-established at Inyati and Hope Fountain as teacher-evangelists and helping to build up the African Church for the LMS. At Mafeking in 1897 a scheme for was drawn up for elementary education which, “is considered necessary to the life and continuation of the work in this field.”[xxxii]

The LMS missionaries wanted twenty teachers immediately to be distributed amongst the Matabeleland districts. They would be married, to teach the three R’s and singing, provided with a house and garden and paid £25 per annum. They would teach for nine months of the year, and when the children were on holiday, would attend a refresher course. As soon as practicable, there would be an annual inspection of each teacher, their pupils and the school by an impartial person. Then one after another, as teachers became available, a network of outstations were opened until over a few years Inyati Mission became the centre of a diocese with the European missionary as bishop.

In 1903 Rev Cullen Reed reported that in many schools, “the best scholars are already up to their teachers and ne or two are in advance of them…there are 23 schools with 2,266 children on the rolls. 19 of these were examined [in the year] at which 1,298 children were present.”[xxxiii] It was felt that the schools had reached their peak and additional help was needed.

In 1908 Hope Fountain added a training school for teachers with an initial class of fifteen and was the first deliberate effort to train African teachers, although in 1909 both the Industrial Institution and training school were forced to close through lack of funding. In 1912 George Wilkerson left and subsequently joined the Baptist Missionary Society.

The Hope Fountain Industrial Institution

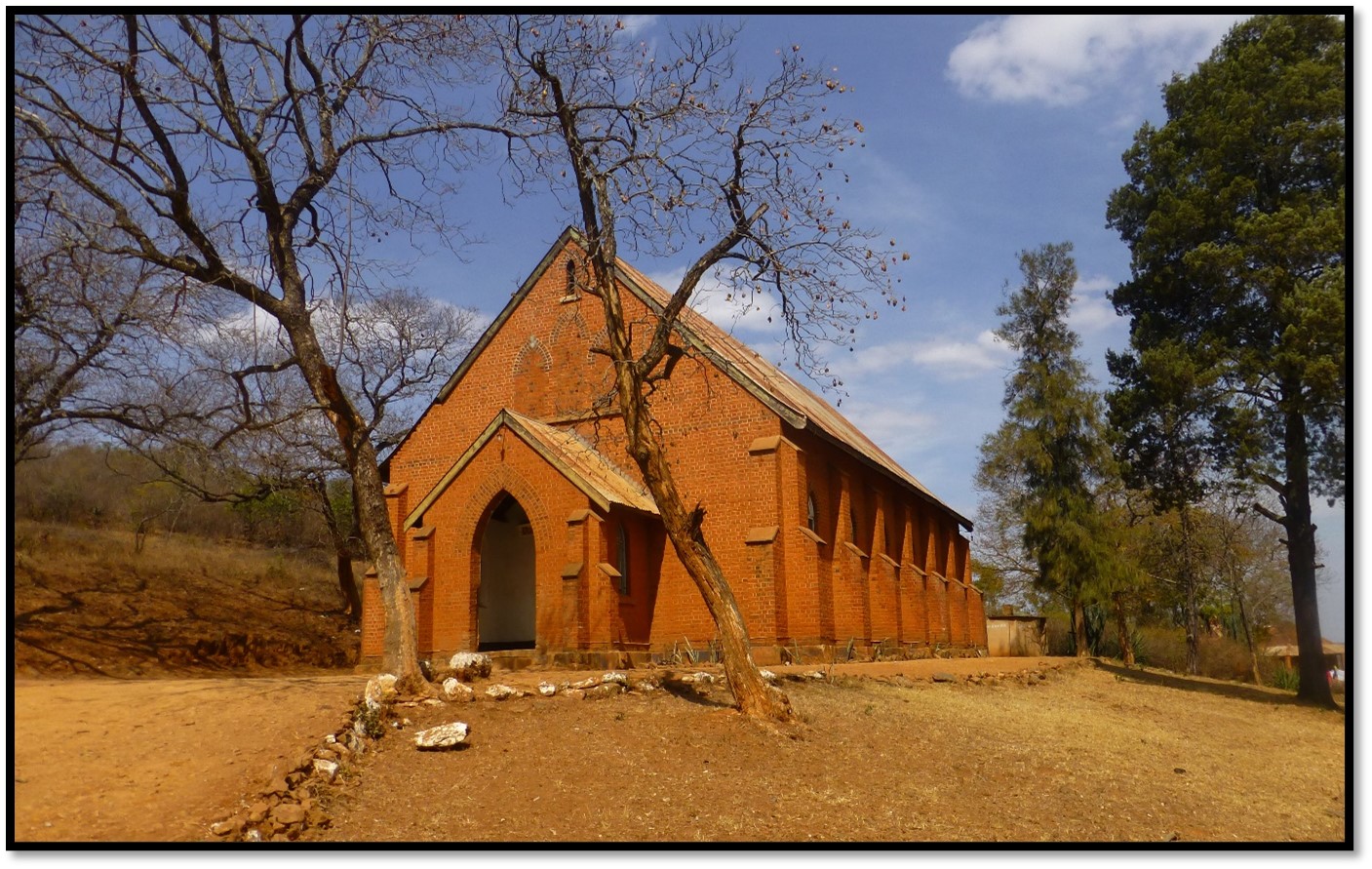

An industrial school was opened at Inyati headed by George Wilkerson, a builder, who was employed as an artisan missionary and by 1898 had three young men under training. Mabuto Gasela, Matjiketje Mkandla and Matjina Ndiweni were the first students at the Industrial Institution at Hope Fountain. Wilkerson aimed at turning out cheerful Christian handymen who after their three year course had learnt carpentry, tin smithing, blacksmithing, building and cobbling and during their last two years specialised in one or another of these trades. The churches at Inyati and Hope Fountain, which they built, are testimony to their skills.

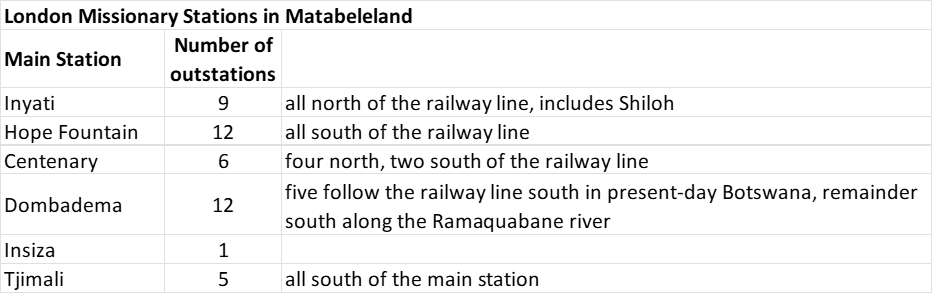

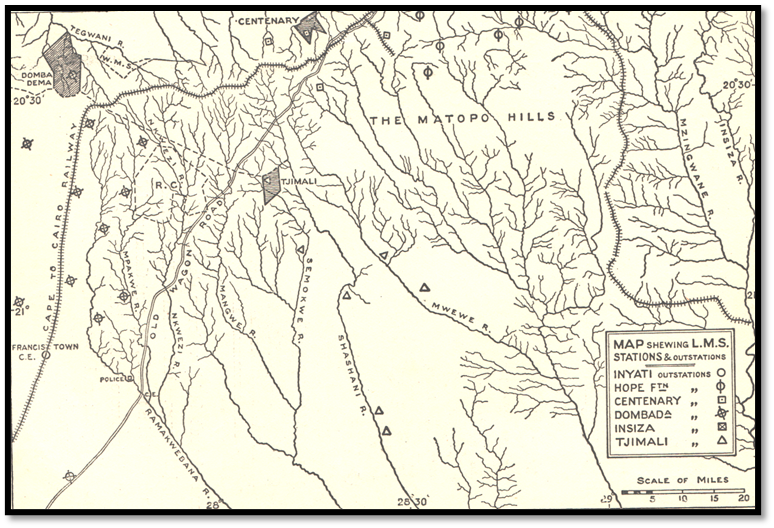

Rev W.A. Elliott: Northern half of map showing LMS Missions and Outstations

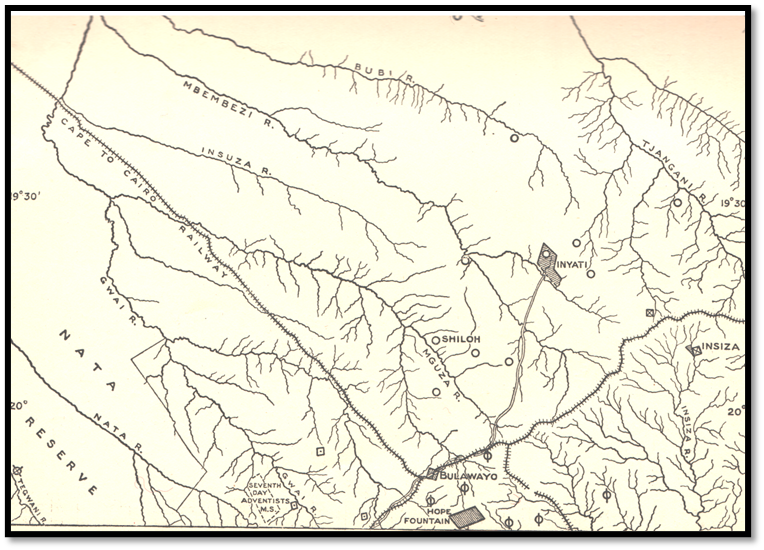

Rev W.A. Elliott: Southern half of map showing LMS Missions and Outstations

Elliott writes that Baleni and his wife Lomaqele, a convert from Hope Fountain, kept the king’s garden at Gubulawayo. He was Amaholi, i.e. from a tribe conquered by the amaNdebele and probably the first native Christian in Matabeleland. After Thomas’s death he moved to Shiloh Mission and ‘held the fort’ and became the resident teacher. In September 1901, of the thirty-four adults baptized at Inyati, thirty of the converts had attended Baleni’s classes for the previous two years.

New Inyati Mission

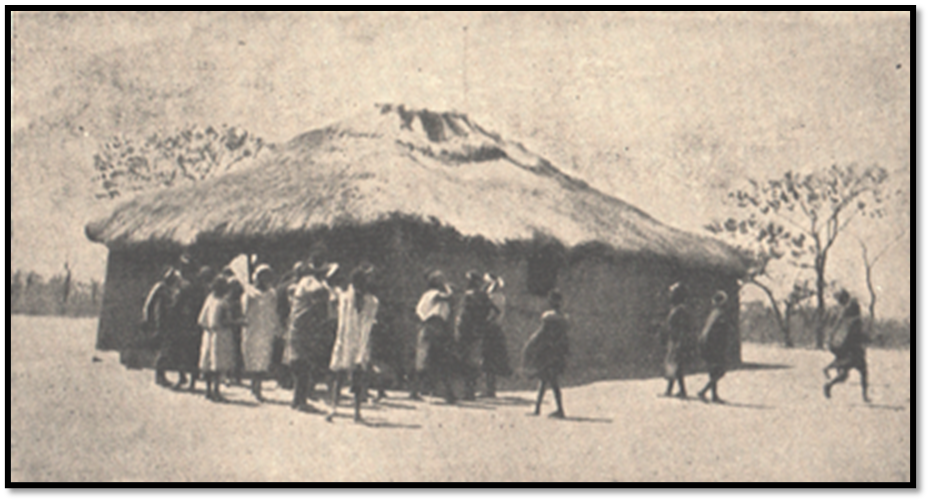

A pole and dhaka thatched church school was built by the congregation by Baleni’s congregation. It was in effect, a huge native hut, being 28 feet (8.5 m) in diameter and so large it could hold a congregation of one hundred people. At the opening on 25 November 1901 great numbers gathered at the usual place in the shade of large tree and after hymns and prayers were led by Mr Rees into the new church, although many had to sit outside.

An outstation was started at Sipongweni in Lupane, Matabeleland North with Samuel as teacher where they built another church and even a house for visiting missionaries.

There were requests from the Shangani river area from Headman Mtjugula and his people for teaching. Nobody was available, but a young boy convert, Manxiweni, with his parent’s permission, was sent from Inyati and taught the men, women and children bible lessons. He stayed for three months before being succeeded by another young convert and finally Matambo Ndlovu took up the teacher’s post.

Elliott says that “it was the same on every side, people crying out to be taught, congregations often crowded and day-schools full to overflowing.”

In December 1901 Rev David Picton Jones arrived from present-day Tanzania after four years residence there to teach at Insiza, but fever brought on his retirement from missionary work in Matabeleland and he moved to Glamorganshire.

A night school was opened and classes in “house-wifery.” By 1906 a new brick church had been built under the supervision of Mr Wilkerson and the boys from his technical school.

Inyati (present-day Inyathi) Church built by Wilkerson and his young apprentices and opened in June 1906

W.S. Elliott: the new day school opened in 1910

Inyati Mission in 1959

Iris Clinton’s description in 1959 goes as follows, “An earth road branches off three miles beyond Turk Mine. After travelling along it for three miles and passing the gaol, the Native Commissioner’s offices and the Police Camp, the road bends sharply and there ahead lies the shallow valley of the Ingwingwisi, with the long ridge of Ndumba (Bean) Hill beyond. Between the hill and the river lies the mission - a long line of corrugated iron roofs shining above the thorn bush.

The mission station is long and straggly. First come the Church and Primary School, old buildings of burnt brick on granite foundations. Within the church, the carved reading desk bears the names of two young Matabele men who suffered, one of them to death, for their Christian faith.

Just beyond lies Teachers’ Square, a group of thatched buildings housing the single teachers, and the minister, the Rev Amos Mzileti and his wife. Down a little slope now and the road passes the football field on the left and on the right the married teachers’ houses built of burnt brick, plastered and colour-washed on the outside and thatched. The teachers put much time and energy into their gardens, which are very colourful and Mr Mzileti’s garden is famous for its beautiful dahlias. On the left, opposite these houses, lies the Quad, the classroom block built in a rectangle round a grassy plot, boarded with flower beds. Here, are also the new Science Laboratory, staff room, school office and a classroom in use as a library.

At this point, there are cross roads. The road to the right passes the carpentry and leather craft shops, the tannery pits, the maze grinding shed, the tractor shed and the main electricity substation housing the main fuses. Inyati is on the main electricity supply line from Bulawayo.

The road ahead leads to the Boys’ boarding department. There are the dormitories, some circular, some rectangular of burnt brick and thatched, the main Hall (the Robert Moffat Hall) used for meals and school assemblies, the kitchen, boarding-master’s house, ablutions block, well and school gardens.

The left hand road continues past two mission houses, the school dispensary and gardens and up the hill to the Girls boarding department. This is a very new building built like an open square, plastered and colour -washed a light green. Here are teachers’ rooms, that domestic science room and washing rooms, opening off the veranda which runs round the inside of the square. The five dormitories, each built to accommodate ten or a dozen beds are the envy of the boys, who have to sleep on mats on the floor in their old buildings. Store, assembly room and office also open off the veranda.

The roads of the mission are lined with trees, mainly jacaranda and syringa, which blossom out into bluebell blue in the spring (October) In the open spaces between, the grass grows breast high and at the end of summer is like a hay field.

The Mission farm, shaped like a letter L, with one arm pointing north and one east, stretches around and beyond the mission station. The inside of the L is the crest of Ndumba, a serpentine hill, and on the outside of the L is a bend in the river Ingwingwisi. The farm covers about 8,000 acres and is divided in half by the mission station, which stands at the corner of the L. The northern arms occupied by tenants, while the eastern arm is run by the mission.

The steam engine that drives the circular saw and dynamo for electricity and African staff housing – both about 1929

New Hope Fountain Mission

At Lobengula’s succession in 1869 he built a new capital at Old Bulawayo, that was just 3½ miles (5.6 km) from Hope Fountain Mission. This resulted in many amaNdebele moving away from Inyati to the new royal town.

At the time of the 1896 Rebellion (Umvukela) the Helm’s were away, as were Mrs Carnegie and Mrs Rees with their children. The converts at Hope Fountain remained at the Mission until faced with an impossible choice by the amaNdebele and were forced to move into the Matobo Hills. Here the women and children endured famine conditions and were forced to catch rodents and feed on the cattle dead from rinderpest.

At the AGM of the LMS on 1 September 1896 and attended by Carnegie, Rees, Reed and Wilkerson they noted, “At Hope Fountain there were absolutely no inhabitants left, but the fort having been evacuated and peace negotiations begun, the people were already sending their women to discover the feeling of the missionaries as to their return, and it was hoped that all would soon be back in their houses as Mr Carnegie purposes going into the Matopos to fetch them in a couple of days, hearing that, they were anxious but afraid to return.”

David Carnegie had visited Hope Fountain during from this period from the laager at Bulawayo and was fired upon, although after some months he and Rev Bowen were able to entice over two hundred of their converts back to the Mission where they were fed by the British South Africa Company.

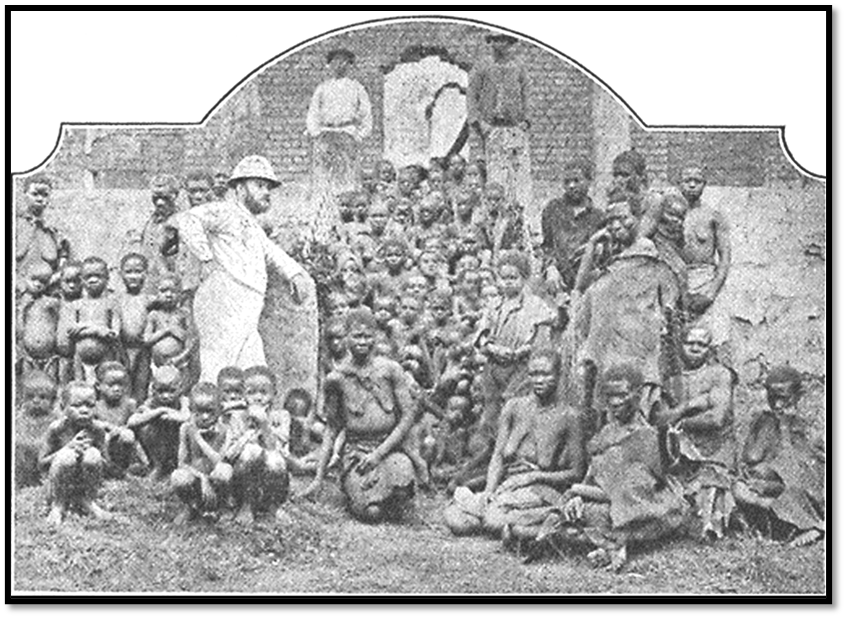

W.S. Elliott: Rev David Carnegie with the congregation at the ruined Mission house, Zhisho in white shirt

There was great rejoicing when after a year Rev and Mrs Helm returned and they were met by Zhisho and his wife Ndawa and the school children with hymns. Hope Fountain was in ruins, but they made do with scraps of broken furniture and odd pieces of crockery.

Elliott writes, “To the native came freedom such as never, not even in dreams, been his. For the first time, this property was his own, his wife and children his very own; and in the morning of that new freedom, his need of sympathetic guidance was very great. He had been conquered and had become free, now he had to learn to use his freedom.

To the missionary came the exhilarating consciousness that he was no longer, as in the olden days, building on sand, beating the air. The work that he was now to do would be suffered to remain and become fruitful; and of this he saw rich promise both in church and in school. Men came in increasing numbers and even the women attended. The congregations were not only larger, they were in quality vast improved. Now keen minds waited on the preacher’s message and bent their unaccustomed strength to the new learning. Never before had such a sense of responsibility burdened the missionary’s heart.”[xxxiv]

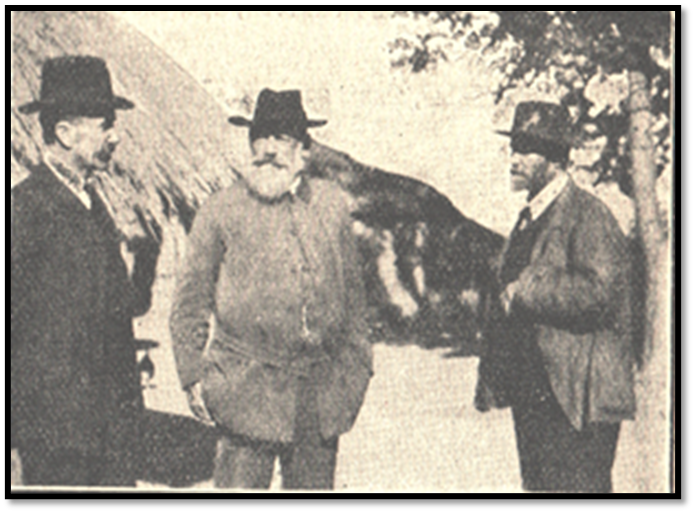

Rev W.A. Elliott: Dr Helm (Dutch Reformed Church) Rev Charles Helm and Rev David Carnegie

The Industrial Institution

Elliott writes that strenuous efforts were made to deal with the new situation. Mr Wilkerson established the nucleus of an industrial institution at Hope Fountain and for several years he and his boys were in great demand at one station after another to build and enlarge. They built the churches and houses of the mission as well as the buildings of the Institute itself. Mrs Helm instructed the girls in sewing and dress making and excellent work was done.

In 1905 George Wilkerson said, “my boys have not the chance to become expert in any particular branch…but I try to turn out Christian lads, tidy, clean, sharp and useful, teaching them to be this by labour which may be building, gardening, etc, mixed with a fair education.”[xxxv]

Rev W.S. Elliott: the student’s quarters at the Industrial Institute, Hope Fountain

It was a great day at Hope Fountain when the fine new church was opened and representatives of nearly all the missionary societies in the country attended.

The young converts from Hope Fountain evangelised amongst the villages within a radius of eight or ten miles every Sunday afternoon. On their return they met together and reported to the missionary what they had talked about and how they had fared.

Msindo, one of the earliest Outstation teachers

The Hope Fountain diocese was very large, the outstations were many miles apart and required constant supervision. Each was in charge of a native teacher, with several substations and nothing would have been possible, but for the loyal cooperation of teachers and church members.

Hope Fountain Church

David Carnegie is a surprising omission from Sibree’s list of LMS missionaries. For more detail and photos of Hope Fountain Mission see the article Hope Fountain Mission under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Rev Charles Helm

After joining the LMS and volunteering for Matabeleland in 1873 he married Elizabet von Puttkamer and reached Hope Fountain on 2 December 1875 with their baby daughter and son. The Thomson’s had just moved into a brick house and the Helm’s took over their Thomson’s pole and dhaka hut. The Helms took the brick house when the Thomson left the next year.

Helm acted as the postmaster for the mail that came by runner fortnightly and were on furlough in England in 1886-8. In September 1888 Helm acted as interpreter for Lobengula in his dealings with Rhodes emissaries, Rudd, Maguire and Thompson and witnessed the concession on 31 October 1888. He left for Palapye during the 1893 annexation of Matabeleland, returning in January 1894.

His wife died at Hope Fountain in November 1913, Charles retired the next year after forty year service and died at Bulawayo on 14 January 1915.

Rev Neville Jones

He was ordained on 23 June 1909, became assistant home secretary of the LMS and married Ruth Collard in 1911 before leaving England for Matabeleland in 1912. At Hope Fountain he organised a girl’s Institute and he and his wife were father and mother to successive generations pf amaNdebele schoolgirls and known and loved throughout the district.

He was in many ways a polymath and in 1933 supervised the excavation site at Mapungubwe for the University of Pretoria. Two years later he took charge of the historical collection of the National Museum at Bulawayo.

Centenary Mission

Unlike in Inyati and Hope Fountain, Centenary Mission Station was the work of one man, David Carnegie. Carnegie and his wife had spent fifteen years at Hope Fountain and there was a happy comradeship with the Helm’s and much sorrow at their departure from the Hope Fountain congregation.

The site, thirty miles (48 km) west of Hope Fountain was in a quiet valley with a clear stream and had been generously donated with 6,000 acres by the Matebele Gold Reef Company, but best of all there was twelve villages within three miles and thirty within half a day’s journey.

Quickly three pole and dhaka huts were built – dining-room, bedroom and kitchen, to be followed by outbuildings for a goat kraal and fowl-house and then a small school house. The ox-wagon was drawn up alongside the school house and between them under a tarpaulin was the workshop. Under a tree, that will always be remembered, the first congregation gathered for Sunday service. By the river a garden was laid out and fruit trees planted.

Just twelve months later in April 1898, the Carnegie family came to a remote siding from where they were fetched by wagon the five miles to Centenary Mission station. The railway had only reached Bulawayo the previous year.

After a nine months of living under thatch Mr Wilkerson came from Hope Fountain with his team and built a brick house and Carnegie hired a Scotchman to build a brick church with Carnegie doing the quarrying of stones for the foundation – a task he much hated! All the native inhabitants in the area donated a minimum six days free labour.

Rev W.A. Elliott: Rev David Carnegie and teacher hauling stones for the church foundation

In October 1899 more than three hundred people crowded into the building along with Rev Rees and Reed, Baleni and Zhisho, although unfortunately Rev Helm was too ill to attend.

In the early days there was good attendance at church and school, but few converts. But gradually numbers grew of both men and women. When the Carnegie family left to take leave, Rev Cullen Reed took their place and when they returned over four hundred native people were at Figtree station, the remote siding now had a name, to welcome them back.

The keen desire of local people to learn astonished even the missionaries and included not only the young, but older men and women too. At the quarterly communion over one hundred people participated.

At headman Mapisa’s village called Sizindeni, a young native teacher called Mhotja was put in charge for one month, but proved so popular that his stay was extended. Sitjenkwa Hlabangana was a teacher at Centenary before training as a minister and ordination in 1921 and serving at Essexvale (present-day Esigodini)

David Carnegie after his fifteen years at Hope Fountain spent a further seventeen years at Centenary Mission and died on 29 January 1910 aged 54 years at Bulawayo Memorial Hospital.

Rev W.A. Elliott: Centenary Church opened in 1899

Centenary Mission was given up in 1913.[xxxvi]

Dombadema Mission (20° 24´ 8" S, 27° 37´ 25" E)

Rev Cullen Reed who had arrived at Inyati in Feb 1895 to replace Rev Elliott saw the need for urgent expansion and agreed to found the new Mission Station at Dombadema (Black Rock) The British South Africa Company donated three farms with over 24,000 acres which had a good supply of water and were well suited to cultivation.

Most of the local people in western Matabeleland are Kalanga and when Cullen Reed arrived in May 1895 they told him they were keen “to hear about Jesus” and the congregations increased steadily in size. In March 1896 the Rebellion (Umvukela) broke out and the Matabele induna Langabi told the local Kalanga headman Mnigau that the missionary was to be killed. Said Mnigau, “If Langabi wants the teacher killed let him come and do it himself” and hurried off to warn Cullen Reed at great personal risk to himself.

Cullen Reed was sitting writing a letter when the messenger arrived, “Master, we must fly, an impi is at Guqwana’s (half a mile away) coming to kill us.”[xxxvii] Cullen Reed with his converts spent the night at a cattle post about seven miles away and had left thirty minutes before the impi arrived to kill him. Next day he met a trooper sent from Figtree to call him into Bulawayo laager.

It was six months before Cullen Reed was able to return and view the burnt ruins of his house, but he was welcomed by local people who hoped that some stability had now returned to their lives. Elliott writes that as a single man he was able to integrate more closely with the local people than if he had been married. He lived in a native-style pole and dhaka hut, ate the same food, observed Kalanga etiquette and learned their language and customs.

Photo: Rev W.A. Elliott, A Kalanga kraal

Elliot writes that teaching began with singing and learning of hymns which they never tired of singing. “Stand up, stand up for Jesus” became a great favourite. But after some time they asked if they could begin to learn to read and this would be added to the curriculum.

A missionaries life is always busy. The house has to be kept, servants told what to do, the cattle and garden cared for, food must be provided for all, there are medical duties - Cullen Reed pulled over four hundred teeth in one year, and the services and classes needed to be organised.

One of the first villages that he visited was that of Tjingababili about 35 miles (56 km) to the south west. Cullen Reed took four young boys from the Dombadena choir to carry their blankets and cooking pot and set off across the Matobo Hills arriving next day when they were welcomed. That winter’s night young and old gathered around a blazing fire and heard their first hymn ‘the Love of Jesus’ led by the young choir boys.

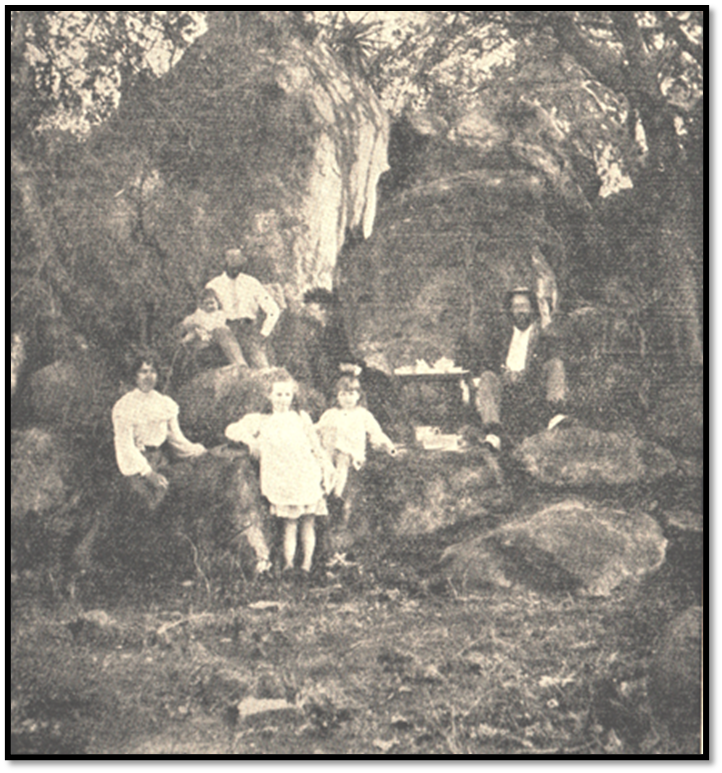

Rev W.A. Elliott: A Matobo picnic near Dombadema. Rev Cullen Reed with hat

The following day he attempted a Sunday service with a reading and a lesson on the ten commandments. Those people stayed on and others from nearby kraals were still coming in on Monday morning to hear what the teacher had to say and by the time he left on Tuesday his voice was hoarse.

The villagers were willing to build schools, but there were no teachers. So the villagers sent six of the brightest boys available to Dombadena for three months training, before they returned to their villages and taught, and at the same time another six young boys went for training to return as teachers.

Insiza Mission

By 1900 it was felt a Mission was needed east of Inyati and Rev Rees found a spot on the headwaters of the Insiza river south of the railway line that closely resembled the conditions at Hope Fountain Mission in a well-watered and wooded valley. Within a radius of 20 miles (32 km) were many villages with perhaps twenty thousand inhabitants. A white settler, Mr Carlessen, generously offered three hundred acres of land at a very nominal rent.

Rev Picton Jones was appointed to the new Mission, but as Rev Rees went on furlough to England, Picton Jones had to take his place at Inyati Mission, and in fact made only one visit to Insiza Mission before poor health made him retire from missionary work in 1903.

Rev Rees on his return did what he could, but no white missionary was sent to share the burden and no native converts were ready to be placed in charge until Zhisho and his wife Ndawa, both Hope Fountain converts, moved from another outstation to Insiza Mission. Soon the Sunday services were attracting congregations of up to three hundred people each Sunday and they giving assistance in building a large, thatched school house and two-roomed teacher’s house with a stone kraal for animals.

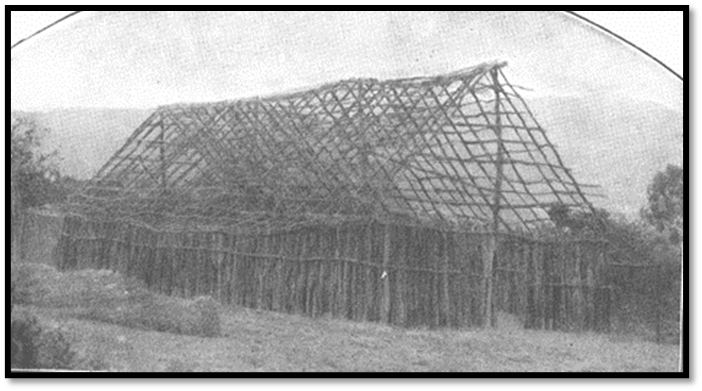

Rev W.A. Elliott: building a school-church at an outstation

Within eighteen months the children were examined and of the twenty-three who were tested on the New Testament, eighteen gained an excellent grade. One hundred and fifty-three children were examined by a visiting missionary – only thirty-seven failed to pass. After his faithful years of teaching Zhisho was ordained as a minister. Outstations of Insiza Mission included Jingeni with its teacher Samuel and Sipongweni with teachers Tandugudla and Egipiti, both with their own large congregations.

Rev W.A. Elliott: native built school church under construction

Insiza Mission was given up in 1911.[xxxviii]

Tjimali

A farm was acquired with 6,000 acres on the Semokwe river in the Matobo, south of the railway and well-watered with good soils. In August 1907 Rev John Whiteside built a road to the site and then a pole and dhaka hut at Tjimali, where he depended on his own resources. He might get advice and sympathy from the other missionaries, but they were far too busy to do more, although he was given a translator from Hope Fountain Mission.

In 1908 Rev Whiteside obtained five teachers and relocated them at outstations and by 1910 his congregations had increased steadily and there were six day schools with over a hundred children in attendance.

Rev W.S. Elliott: an Outstation school church

Ingwalo

This word refers to missionary literature, although its origin lies in the Shona word for decorative markings on wooden bowls. The mystery of the written word to the illiterate is well illustrated in this note by Rev Elliott. One day a man came to Rev Charles Helm with a disease requiring medicine that Helm had no stock. So he said, “Give me a note to Eliyata (Rev Elliott) that he may give me the thing that I want.” Once he had Helm’s note, he cut a stick, placed the ugwalo (singular of Ingwalo) in the split, tied the stick tightly together above and below the note and walked to Inyati forty miles away. Arriving, he handed the stick with the note to Rev Elliott, narrowly watching what happened. The missionary read the note and told the man to sit down while he went to get it. “Get what?” said the man. “Do you not want such a medicine?” “Yes,” replied the applicant, “But how did you know?” “Did you not bring me the ugwalo asking for it?” “Truly, but I never heard the ugwalo speak to you.” “Perhaps not” replied Rev Elliott, “but I did hear it.”

References

D. Carnegie. Among the Matabele. The Religious Tract Society, London, 1894

I. Clinton. These Vessels…The Story of Inyati 1859 – 1959. Stuart Manning. Cape Town, 1959

W.A. Elliott. Gold from the Quartz. London Missionary Society. Simpkin, Marshall Hamilton, Kent and Co, London 1910

James Sibree. London Missionary Society. A Register of Missionaries, Deputations, etc. from 1796 to 1923. London Missionary Society, London 1923

O. Ransford (Text) Rhodesian Tapestry, A History of Needlework, Embroidered by the Women’s Institutes of Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo, 1971

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town, 1966

Notes

[i] The London Missionary Society is these days called the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA)

[ii] Rec Hepburn came to Shoshong in 1871. He went to Shoshong in August 1889 where both he and his wife suffered from fever and left in October 1891 after a quarrel with Khama III

[iii] Robert Moffat was born in Ormiston, Scotland in 1795 and after school apprenticed to a gardener. He then entered theological college and in 1816 was accepted by the London Missionary Society. In 1824 he founded Kuruman Mission station in the northern Cape and in 1829 met Mzilikazi for the first time. When he left for Matabeleland in 1859 he was 63 years old, but with great experience of trekking and a commanding personality.

[iv] Gold from the Quartz, P35

[v] For a summary of the amaNdebele journey to Matabeland see the article Early traveller’s impressions of Gubulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vi] Sam Edwards (1827-1922) an old hand who served at different times as hunter, trader, explorer, transport manager, interpreter, guide, mine manager and British agent. He had served as transport manager to the London and Limpopo Mining Company at Tati. In 1881 he tried to get a mineral concession from Lobengula and was given the abandoned Tati concession for an annual £50 rental and stayed here for the next ten years as managing director of the Northern Light Company and served as Lobengula’s ‘immigration officer’ in much the same way as John Lee. Very popular with travellers and good friend of Baines.

[vii] David Livingstone who married Robert Moffat’s daughter, Mary, had come to South Africa and worked for eleven years with the LMS in Bechuanaland. In 1849 he and William Cotton Oswell journeyed to Lake Ngami which awakened his interest in exploring the Zambesi and in 1852 he set out on his amazing journeys.

[viii] These Vessels, P22

[ix] John Moffat, son of Robert, was deeply religious, liberal in outlook with a keen sense of justice and explosive temper on occasion. His salary was paid by David Livingstone until 1864 when he received a letter saying the Zambesi Expedition was recalled and he could not support him any longer. He then applied for a post with the LMS. However because of his wife Emily’s ill-health and his discouragement with the lack of success making converts, they left Inyati in 1865 and was his father’s assistant at Kuruman until 1870 when Robert retired and then in charge until 1877. He then took government posts. Native Commissioner at Zeerust until 1881, Resident Magistrate at Maseru, Basutoland until 1884, then at Taungs until 1887 when he was appointed Assistant Commissioner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. In 1888 he was British Resident at Gubulawayo and on 11 February obtained Lobengula’s mark on a treaty of friendship with Britain.

[x] Thomas Morgan Thomas started work at 7 years old on a Welsh farm and educated himself sufficiently to train for the ministry at Brecon College in Wales. He felt out with Sykes and John Moffat and eventually the LMS because he traded to supplement his poor salary and gave presents to the amaNdebele for attending church and school. Wrote in 1872 Eleven Years in Central South Africa which describes not only mission work, but amaNdebele customs, fauna and flora. His wife Anne died three days after their third child had died on 7 June 1862. He married Caroline Elliott and brought her and his two elder sons to Inyati. He successfully treated Mzilikazi’s gout which greatly increased his standing. In 1867 he walked to the Zambesi Valley but did not see the Victoria Falls. After Mzilikazi’s death he interfered in amaNdebele politics and was present at Lobengula’s coronation at Mhlahlandhlela in on 22-24 January 1870. In 1875 he moved away from Inyati to a new mission at Shiloh given to him by Lobengula where he lived for the rest of his life teaching, trading and farming and died there on 8 January 1884

[xi] These Vessels, P30

[xii] Ibid, P32

[xiii] Robert Moffat writes that Monyebe was the king’s prime minister

[xiv] This was on the anniversary 299 years before of the arrival of the first Portuguese missionary on the northern Mashonaland plateau. See the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xv] Gold from the Quartz, P49

[xvi] One of the Bechuana servants, Marelole, died on 18 April 1860 and was the first person buried in Inyati cemetery

[xvii] Gold from the Quartz, P59

[xviii] These Vessels, P26

[xix] Ibid, P44

[xx] Gold from the Quartz, P124

[xxi] John Lee, hunter and trader first hunted elephant in Matabeleland in 1862 and in 1866 settled at Mangwe on land granted to him by Mzilikazi. In the early days of the gold rush at Tati he marked off claims and interviewed diggers. He became trusted by Mzilikazi who appointed him as agent and adviser in his dealings with Europeans.

[xxii] Gold from the Quartz, P127

[xxiii] Thomas Morgan Thomas who had left the LMS under a cloud for meddling in Matabele politics and trading and set up a new mission station at Shiloh

[xxiv] Lobengula granted Hope Fountain Mission 6,000 acres of land

[xxv] The builder was an old sailor named John Halyet

[xxvi] These Vessels, P54

[xxvii] Heritage Vol 41, P13-16 has a good article on the malevolent influence of these ‘doctors’ written by Prof. R.S. Roberts called The Mzizi Family: War Doctors to Lobengula

[xxviii] Gold from the Quartz, P144-5

[xxix] Ibid, P145

[xxx] Their names are honoured on the pulpit of present-day Inyathi church

[xxxi] European deaths in the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) totalled 260; in the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) they totalled 150

[xxxii] These Vessels, P64

[xxxiii] Ibid, P67

[xxxiv] Gold from the Quartz, P174

[xxxv] These Vessels, P69

[xxxvii] Ibid, P200

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: