Home >

Matabeleland North >

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa in 1891-2 (Part 2 of 5 - Arrival in the Barotse Valley)

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa in 1891-2 (Part 2 of 5 - Arrival in the Barotse Valley)

29 November 1891. “This morning, instead of starting, the carriers, led by two rascals, Bwete and Kesongo (who have been at the root of almost every trouble we have had on the road) conscious that they had exacted from me much more than was due for rations and fearing I should take it off their pay on getting to the Barotse, refused to take up their loads unless I paid every man, in full, here and now. They strutted about all day, thinking, no doubt, I should be obliged to comply.”

He called the headmen together and said they could do as they pleased, but he would be leaving tomorrow for the Barotse capital and if necessary would send carriers back for the loads and they would lose all their pay. They promised to start as they were within three or four days of Lealui and there all accounts would be squared.

30 November. Two men are sent, as is customary, with a letter and presents of cloth to King Lewanika, requesting permission to enter his country with a letter also for Monsieur Coillard, the French missionary.

Envelopes are slipped into a cleft stick, which is tied with bark. “When the messenger rests, the free end is stuck in the ground and they hold it prominently as they travel, the sight of an omakand (paper that speaks) generally securing for them a measure of protection when passing among strangers, as they recognize the fact that there must be a white man not far off.”

Their food supplies are very low, Johnston’s rations for the last two days having been a few crackers with two ears of roasted mealies.

They are now in the Barotse Valley, the natives being subjects of Lewanika, although most are also slaves belonging to village headmen who have been captured in raids and war. The women make no attempt at hairdressing, plaiting, or ornamenting; a few have beads around their necks and most of them have rings of iron and brass on their arms and ankles. There are no flintlocks among the men but bows and arrows and assegai’s. “This morning I saw cow’ s milk for the first time since coming to Africa and they promised to bring a gourd of fresh milk tomorrow.”

2 December. “Several villages are in sight, but the natives are very shy. About 3pm the two men I sent off on the 30th with letters to the king and Monsieur Coillard returned and to my dismay and chagrin, said they found no white people and that the king had forbidden, on pain of death, any white man to enter his country. They could give no reason for having failed to deliver the letter to the king.”

In the morning he takes Jonathan, one of the Jamaicans and a guide and sets out for Lealui.

Soon they reached the Zambesi and crossed by canoe, which at this point was 135 metres (150 yards) wide at what was called the Mongole drift and had hippos in the river. Another hours walk took them to the Kimbo river, wide but not deep, and the guide carried Johnston across on his shoulders. Small cattle grazed on the grass and there flocks of wild geese and ducks everywhere. In another four hours they were at Lealui where he had a hearty welcome from an English trader.

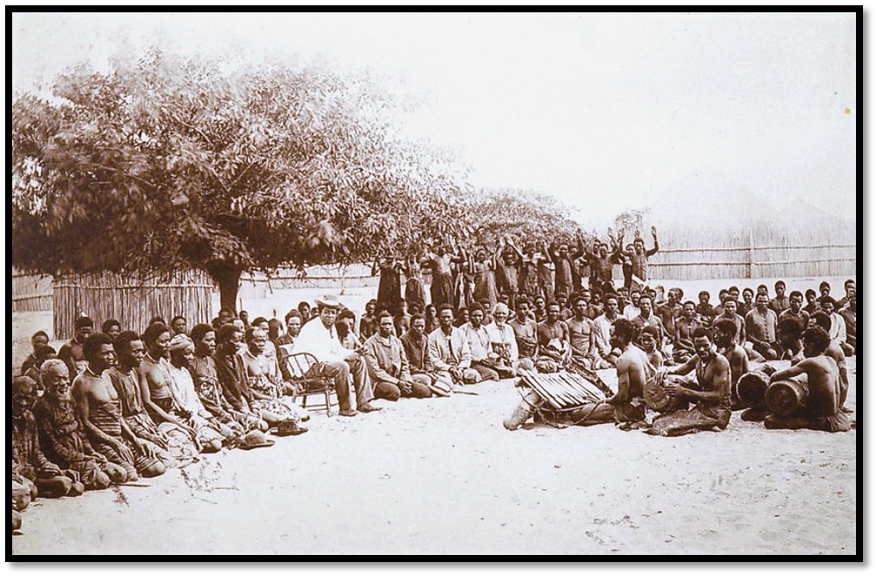

He writes: “I went to see Lewanika, whom I found sitting in his ‘lekhothla’ or courtyard, in the centre of the town, with a crowd of people kneeling in semicircles before him, near or far according to their rank. The deep, yielding sand is a merciful provision for those who have to remain in this position for hours together. I was graciously received and could not but feel that at last I was face to face with a real African king, compared with whom the many I had seen were but insignificant. Lewanika was plainly dressed in English clothes and sat on an ordinary cane bottom chair, his manner was affable and free. In front of him were his band of drummers and marimba players. Each company of men, as they assembled at the evening council, while still at some distance began clapping their hands in unison and before taking their places raised their hands above their heads and shouted the royal salutation, ‘Yo sho, yo sho, yo sho, Tau Tuna’ (great lion) After kneeling, they continue clapping, and bow their faces to the earth three times.“

Lewanika paid no attention to all this pomp and ceremony and kept up a long conversation with Johnston through an interpreter. He could not quite understand why I had come so far simply to see the country and the people as he said: “All the white men who come here either want ivory and skins, or liberty to hunt in my territory.”

King Lewanika holding court

Barotse (or Lozi) Greetings

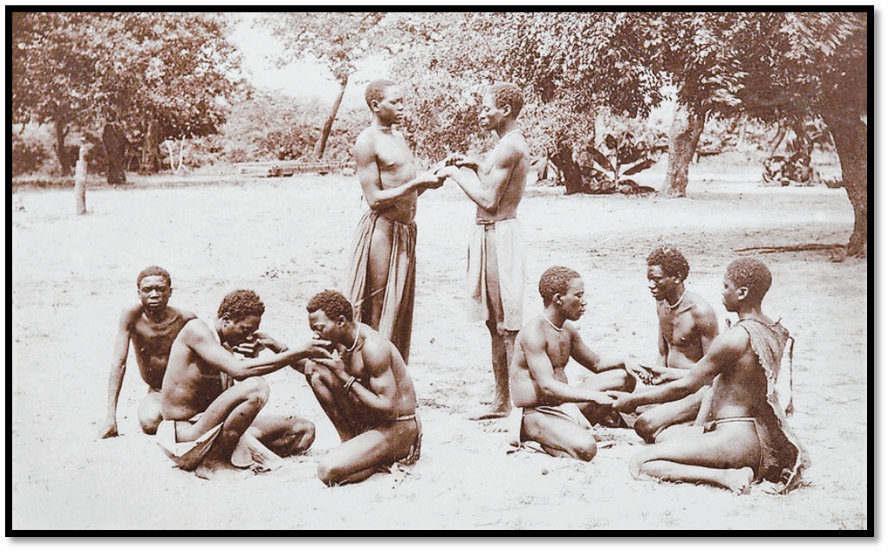

Johnston describes the various forms of greeting.

Superiors are approached by clapping the hands and repeating the word ‘lumela’

For equals there are three types of greeting according to their friendship or relationship:

- Those having a slight acquaintance with each other will on meeting lay down their spears or whatever load they may be carrying and seizing each other by both hands, elevate them to about the level of their eyes, lowering and raising them three times silently gazing into each other’s face and conclude by squatting down and sharing a snuff-box.

- Where there is a closer friendship; the same ritual above is performed, but in this case the parties kneel.

- Where they are near relations, each with his right hand seizes the left hand of the other, palm upward and gives a prolonged kiss, or kisses, according to the closeness.

Barotse greetings

4 December. Lewanika sends a messenger: “with his greetings and to know if I had slept well; at the same time expressing his desire that I should live in his village during my stay in the valley and stating that a house was already prepared for me. He also sent an invitation to lunch with him at noon.”

Noon found Johnston and the English trader at the entrance of the royal enclosure built of reed mats that surrounds the twenty large huts of his numerous wives. Lewanika was sitting at the door of his house talking with his secretary, but on seeing us, rose and bid them welcome. His building is in bungalow style and was built by natives under the direction of Mr Wardell, a Scottish carpenter, who stays at Sefula, south of Lealui, Monsieur Coillard’s mission station.

5 December. Still no sign of my caravan. I told the king, who immediately sent a messenger telling them to come at once. Before nightfall they were at Lealui and looking very frightened. “I never saw such a change in the demeanour of my men.”

Today they have been celebrating at the ‘lekhothla’ the great native festival of the month – the dance of the new moon. Drums have been beating since early morning and at midday about three hundred men were dancing, all dressed in kilts of leopard’s tails and ostrich feathers in their hair and it lasted until sundown. Every night beginning at 10pm there is a dance of a couple of hours and the drumming continues until daybreak to drive off any evil spirits that might disturb the king’s sleep.

I am in one of two huts provided by the king; the two Jamaicans are in the other. The huts consist of two circular reed walls, one inside the other, plastered with a mix of cow-dung and anthill sand. The floors are made of the same material well-trodden down and smoothed with ox-blood. The roof is made of closely woven reeds and thatched with grass and extends over the outer wall giving an inner and outer compartment to each hut, which having no windows, are very hot. The door is just 120 cm x 76 cm (4 feet x 2½ feet) wide.

6 December. “The chief ’s secretary, Sajrka, who has been educated in Basutoland had a service in the village, reading a portion of scripture and singing some hymns with the boys who are under the tuition of Monsieur Coillard at Sefula; but in the evening the drums beat and the dance goes on as on other nights, loudly and fiercely until two o’clock in the morning There is a manifest struggle going on here between light and darkness; so far, the latter is in the ascendency…

I spent three hours of the afternoon with the king, our conversation being interpreted by a black boy, who knows a little English, having been brought up at Cape Colony. Lewanika says he longs for light and knowledge and wonders why more missionaries do not come to teach him and his people. It must not be imagined by this, however, that he yearns for a knowledge of the gospel. By no means, he wants teachers to instruct his people how to read and write, but especially to train them as carpenters, cabinet makers, blacksmith's and for other trades that they may make furniture and build houses for him. None of his people dare own a chair or build a square house or put a wooden door or window in their hut, the right to possess such luxuries he reserves to himself. But he has a great idea of the ability of the Barotse to learn the various arts and become wise like Europeans.”

He is currently building the annual Nalikwanda canoe. This is made by breaking up normal canoes for their planks and constructing a monster flat-bottomed canoe measuring 37 metres x 4.5 metres (120 feet x 15 feet) and will take him with his wives to his mountain village 21 km (13 miles) where he spends a couple of months each year when the plain is covered in the Zambesi’s flood waters. When they dry up he returns and a new canoe will be built next year.

Photo Wikipedia: the royal barge goes from Lealui to Limulunga

7 December. He pays off his carriers today without a single complaint from any – they are afraid he will tell the king of their poor behaviour on the road. Each is given what they were promised, but no bonus.

The king gave Johnston a fine ox today which he has had slaughtered and the meat distributed to the sub-chiefs. Firewood is scarce and has to be carried 23 km (14 miles)

9 December. I spend 3 – 4 hours each day with Lewanika, discussing every question relating to black people and especially about Jamaica. He has been very kind to us, yesterday we had dinner with him. It was a very good attempt at English style, but for the slave waiters who in bringing in or removing each dish did so crouching on their knees (no native is allowed to stand in the king’s presence) and when the meal was finished the five slaves knelt in a row at the door and clapped again, thanking him for being pleased to eat the food they had served.

When I asked to visit Monsieur Coillard at his mission 30 km (18 miles) away at his mission at Sefula the king lent a horse and men to carry baggage.

Lewanika in war dress

The reason I heard that white men had been banned from visiting earlier is because of what the king believes is bad treatment from the British South Africa Company (BSA Co) For years he has been writing to the British government asking for his territory to be included under a British protectorate as in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) further south. Last year (1890) he was visited by an agent (Lochner) of the BSA Co who brought presents and asked for a monopoly of mineral rights. The king signed the concession believing protectorate status would be issued. In return, he asked the agent to present Queen Victoria with the finest tusks he owned.

But no acknowledgement of protectorate status came from the British government and his suspicions were confirmed when the following statement was read to him: “Mr Lochner and the king parted in the most amicable manner, his majesty returning the traveller’s present by the gift of two fine tusks of ivory, each considerably over one hundred pounds in weight and over six feet long. These now ornament the board-room of the British South African Company in their palatial office in St. Swithin’s Lane.”

Lewanika was filled with rage and he considered all Englishmen “thieves and robbers.” Unfortunately, Monsieur Coillard and his colleague Monsieur Jalla were seriously compromised as they acted as interpreters for the agent. Letters were written in protest by Coillard on the king’s behalf to the British government protesting the mineral concession: “Now, if the aim of the BSA Company is what it is represented to the king, a mere gigantic mining and land-securing scheme and if the British Protectorate has been used simply as a blind, I emphatically protest against it and regret if I have unwittingly been a dupe and an accomplice in such transactions.”

Lewanika forwarded an emphatic protest to the British government in August 1891 against the Lochner concession. The BSA Co of course denied that their agent tried to pass himself off as the Queen’s representative; but the facts show otherwise.[i]

Life in the Barotse Valley

10 December. Johnston and a guide rode south for two and half hours to the mission at Sefula where he meets Monsieur Coillard of whom he has heard so much and is introduced to Miss Keiner, a Swiss lady teacher and to Mr Waddell, the Scots carpenter. The mission station is situated on a beautiful plateau at the end of the low range of bills running along the east side of the Barotse valley.

Sefula, Monsieur Coillard’s mission station

He writes: “It might well lay claim to the title of a model mission station, it is so fully equipped with every appliance for instructing the natives, not only in divine things, but also how to improve their social condition.” The mission has a saw-mill powered by six oxen, brick-making machines, a smithy with a forge, a workshop fitted with every tool. All the buildings, including the trim little church, displaying skilled workmanship.

He is grieved to find Monsieur Coillard in a very low state of health and depressed in spirits as his wife, the devoted companion and helper of his thirty years’ in Africa had died a few weeks before.

Monsieur Coillard at his wife’s gravesite

Coillard tells him regarding their progress: “It is now seven years since our expedition crossed the Zambesi and the mission was started - a long time in one’s short life; yet we are still passing through that arduous and uninteresting period of breaking the fallow ground and sowing the seed…These last three years have been to us more by far than all our missionary life years of toil, trials, and suffering. The social and political state of the country has been greatly disturbed by internal causes and the advent of the British South Africa Company. Sickness and death have thinned our ranks as quickly as we had the joy of receiving helpers from Europe, at great expense and we have seen our brightest hopes and our dearest plans blighted and dashed to the ground.”

From this statement comes the title of his book as Johnston writes: “Such is the aspect of the most faithful mission work in reality. Of romance we have already had far too much from visionaries, who deem it essential to write such accounts for the purpose of keeping up the interest, particularly if they are not guaranteed support but have to depend upon casual voluntary contributions.”

He states that a great mischief is created when missionaries claim that Africans “are ready and waiting to receive the gospel” as the reality is quite the opposite. The writers of these articles are not to blame alone, as the routine of well-established mission stations seldom provide ‘thrilling’ tales, but committees and supporters require something significant for their quarterly or annual meetings. There is always a danger that the church at home may be misled by false reports of marvellous success.

Of the missionary workers in Matabeleland and the Barotse valley he says: “They are all foundation workers, toiling deep down in superstition and gross darkness and spending their lives almost unknown, amid dangers and discouragement, without a soul to cheer by responding to the message they bring, receiving no sympathy from their surroundings and hundreds of miles perhaps, from the nearest fellow labourer.”

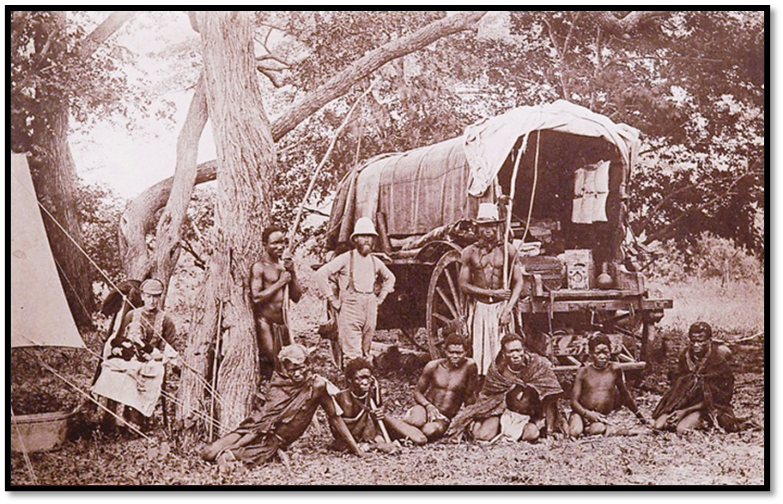

Primitive Methodist Missionary Society (PMMS)

Johnston writes that Mr B. representing the PMMS was camped near Sefula with his wife and child hoping to get permission from Lewanika to settle in their country or be allowed to go through to the Ila (Mashukulumbwe) peoples in the south to organise a mission station. The king, however is not favourable saying: “They had better go back, for they are not wanted.” Poor B. I am sorry for him, but still more so for his wife and delicate little girl, whom he takes about with him in the wagon trekking these many months.[ii]

Mr B of the Primitive Methodist Missionary Society

21 December. We returned to Lealui on the 14th, but I have been busy every day visiting and prescribing medicines to the sick in the village, including nine of the King’s wives. This prevents me from getting away and proceeding on my journey. “However kindly the white traveller may be received and treated by a powerful heathen potentate like Lewanika, he is soon made to realise that his position as a guest is virtually that of a prisoner, for he cannot leave the country, nor dare a porter lift one of his loads, except by the King’s permission.”

Magwai, Queen of the Barotse and slave girls

The romance of life among the Barotse is of short duration after the first few days. The traveller is interested in observing their manners and customs, the native smithy, under shade a group of men make karosses (blankets) from animal skins. In another corner, woodcarvers are making bowls with native hatchets. Elsewhere basket-makers are using reed grass to make vessels for carrying water.

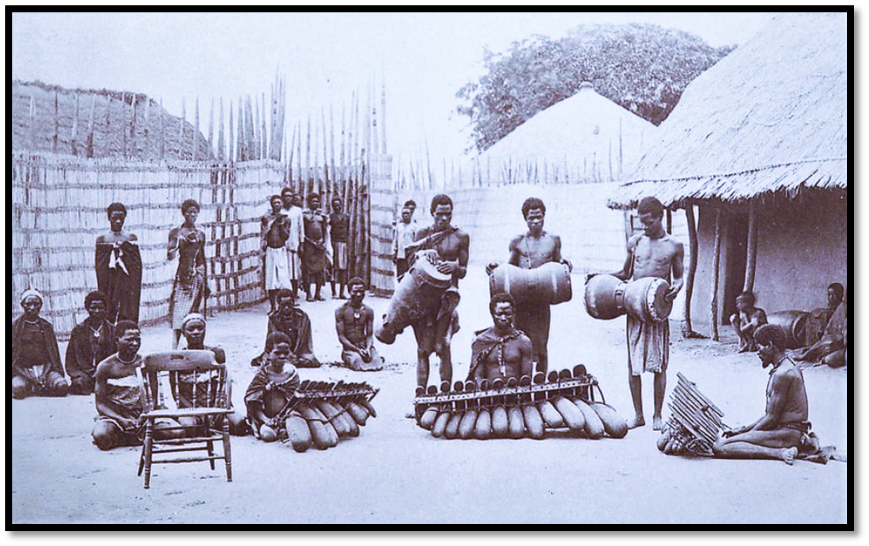

In the evening, with much pomp and ceremony, preceded by his band of drums and marimbas, his majesty comes out to the lekhothla where hundreds of his subjects are gathered and kneeling in their usual semi-circles around the royal mat with a chair for the white guest to hear while court is being held. The case may involve witchcraft, poisoning or cattle stealing or it may be to receive tribute from distant tribes as far north as Lake Bangweulu and south to Lake Ngami who occupy lands supposed to be within Lewanika’s dominions.

King Lewanika’s band comprising drums and marimbas

Ancestral worship

Ancestral worship is still the religion of the Barotse nation, the theory being that although their ancestors have departed this life, their spirits still haunt the scenes of their earthly career, potent to wreck vengeance on those who may have incurred their displeasure. Although Lewanika regularly visits the tombs of his predecessors to pray to them and is generous in his gifts of oxen as peace offerings, his conscience reminds him that some did not receive fair play at his hands and so the drums and noise at night to keep them away.

For several days Mambundas, a hill tribe and the recognised sorcerers in the Barotse valley have been throwing down their divining tables and shaking baskets to establish whether the Barotse should go to war with the amaNdebele under Lobengula. The answer seems to have been that the gods were angry with the tribe and refused to answer. This was convenient, as the Barotse armies are too weak to take on the amaNdebele and if they were beaten in a war authorised by the diviners would be blamed for the defeat!

The Barotse Valley

The valley is covered by the floodwaters of the Zambesi river annually to a depth of 150 – 245 cm (5 – 8 feet) and the villages are built on mounds to keep them out of the water with canoes the only means of travelling for several months. The grass rots when under water and stagnant pools are left when the floodwaters retreat so that malaria is ever present. “In the wet season the heat and moisture keep one in a perpetual vapour bath. Today my hands and arms are puckered from perspiration, as if I had spent hours at the washtub.”

Wikipedia: Zambezi river and Barotseland, Zambia with NASA satellite photo of the floodplain

Lewanika’s son is married

30 December. After Coillard conducted a Sunday service at Lealui he persuaded me to join him at Sefula. Lewanika’s son is getting married here on New Year’s Day and both Lewanika and the Queen, who is Lewanika’s sister, have arrived. She rules the kingdom with Lewanika from her base at Nalolo, a day’s journey down river. Johnston writes: “She is a much more determined character than her vacillating and pusillanimous brother. Her reign is stained with many a cruel act of murder and bloodshed, avenging herself, particularly on those who are in anyway the objects of her jealousy.”

Prior to the wedding on New Year’s Eve crowds of people were treated by Coillard to a fireworks display, which seemed to amaze them greatly. He puts himself to no end of trouble to create interest in the mission station and if it’s a magic lantern exhibition they will come in flocks.

1 January 1892. “Yes, another year is gone and one that to me has been fraught with the strangest and most varied experiences that have fallen to my lot during my somewhat checkered life. This time last year I was surrounded by all that makes life sweet, in a land where there is light, joy, peace and love; here, darkness, wretchedness, strife and hate abound. While writing, I hear the ghoulish yells and wild revel of the natives as they celebrate the opening year. Knowing no joy but in that which panders to their basest passions, love is to them a myth and peace they have never known, for war and bloodshed is their special delight.”

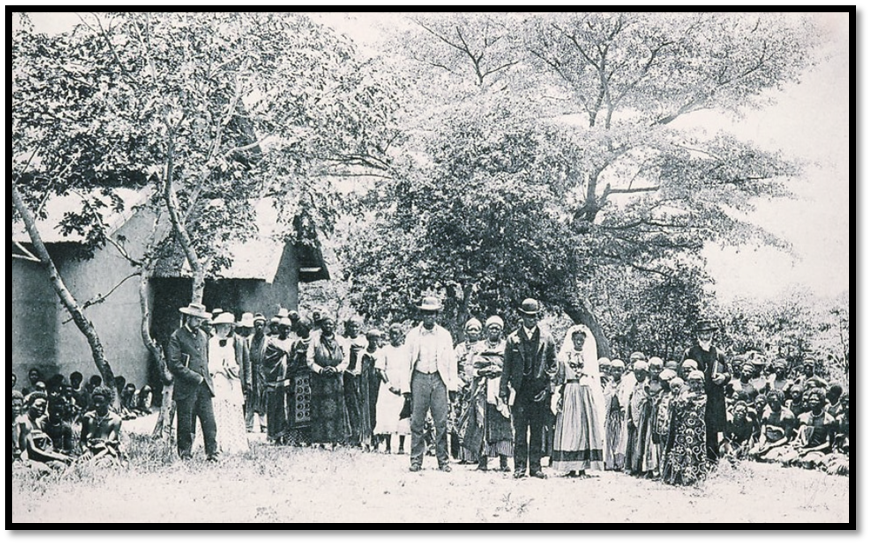

Lewanika’s son’s wedding at Sefula mission station

“This has been a great day in the Barotse Valley and at Sefula as the first marriage, christian or heathen, has been performed by Monsieur Coillard, in the union of Letia, son of Lewanika, and Makabi, daughter of Katusi, a minor chief. The girl has been for some time in the school at Sefula and much care has been bestowed and many months spent in the endeavour to wean her from her heathenism, but without success. Still, Letia has made a profession of christianity and wished to be married by the missionary. The bridegroom and groomsmen were neatly dressed in suits of tweed; the bride decked out in a dress of yellow lustre trimmed with furniture chintz, the material having been brought from Mangwato by Letia and made up with his own hands, Miss Keiner cutting it out and adding the finishing touches.

By 11am thousands had assembled at the little church, which was taste fully decorated for the occasion with fronds of the fan palm and leaves of the wild plantain. Flowers are scarce in these parts. The most important among the people obtained admission until the building was crammed, while the mass had to be contented with standing room at a distance, or a peep in at the windows. The ceremony proceeded without an interruption until the bridegroom promised to cleave unto this wife only so long as they “both should live” when an audible titter of amused scepticism passed round among the chiefs, beginning with his father, who rejoices in the possession of over a score. And he would be a small chief indeed who could not boast of at least half a dozen women in his harem.”[iii]

Monsieur Coillard proposed having the wedding lunch in the open air. But it was difficult getting the bride to sit on a chair, she had never sat at a table in her life or used a knife and fork. Then Lewanika objected strongly to the Queen and his chief wife sitting opposite him; he said he had never eaten with women and never would! A compromise was reached by pulling his chair back from the table. Then when his sister’s husband and his own secretary were invited to the table Lewanika declared no Barotse should ever sit in his presence except on the ground and they were forced to leave!

Johnston says it proved to him how totally impossible it will always be to influence for good, civilize or elevate a people tyrannised over by such an arrogant, ignorant autocrat such as Lewanika.

4 January. There’s a blissful stillness at Sefula today…royalty has left. The Queen and her entourage by canoe to Nalolo, the King by horse back to Lealui. He says he is not sorry to see the last of them as they will get some quiet rest tonight.

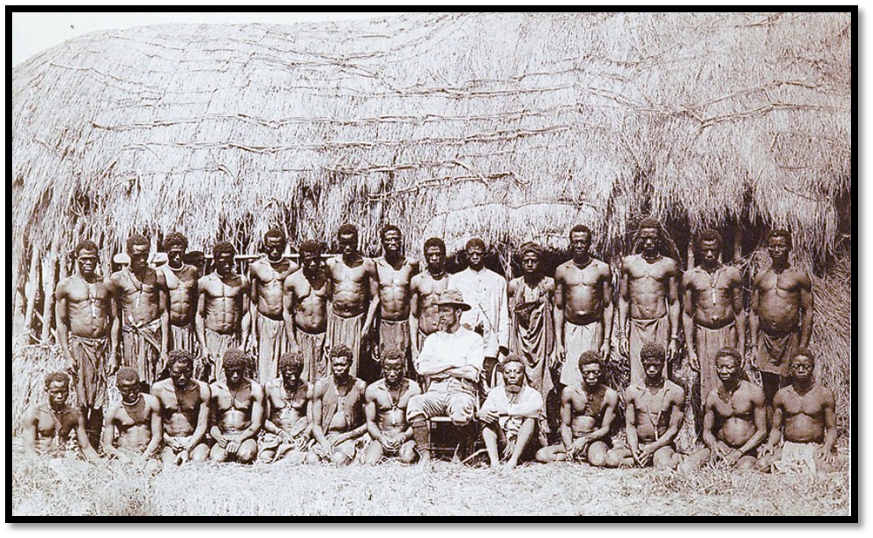

A band of Mashukulumbwe arrived at Sefula this morning enroute homeward. They have been on an embassy to the court of Lewanika, carrying tribute, and declaring their desire to live at peace with him, having lost heavily to a raiding party of Barotse who entered their country last year and captured a great number of slaves and cattle. These are representatives of a wild but little-known tribe, little known beyond the fact that every expedition led by whites who have attempted to visit them came to grief, including Dr Holub and Mr Selous, who in each case were obliged to flee for their lives.

Mashukulumbwe natives at Sefula mission station

We grouped them for a photograph. It is necessary to exercise much patience and tact while endeavouring to get photographs of natives. They are so suspicious, it is hard to persuade them that posing in front of the machine will not in some way bewitch them. But I found the most successful argument was to politely request permission to ‘take their measure.’

Some travellers have said that photography in Africa is impossible, because equipment will get smashed in transit. So far, my experience in this direction proves that in transporting a photographic outfit, there is no difficulty whatever and far less risk of breakage than if travelling in Europe, for damage from rough treatment is the last thing that happens to a load in the hands of an African carrier. They are not ‘baggage smashers.’

From Sefula to Sesheke

A canal has been cut from Sefula to the Zambesi about 9 km (6 miles) in length and connects a series of small lakes and was paid for by a friend in Scotland. The king was so inspired he set thousands of his slaves to work to cut a similar canal 4.5 x 1.8 metres (15 feet x 6 feet) not only to Lealui from the Zambesi but extending north a further distance of 32 km (20 miles) that is navigable by large canoes.

7 January. Today he met with the king and presented him with a Winchester rifle, a suit of tweed and Jaeger wear and requested carriers for the next stage of his journey which the king promised to do.

While visiting sick patients he was told that a headman had added a new wife to his harem, but his jealous oldest wife had puy poison in her bread, fortunately he was able to give the victim an antidote and the young woman did not die. He saw the oldest wife and a slave tied up by their hands and feet…they are to be thrown into the Zambesi and fed to the crocodiles.

14 January. We are to leave tomorrow and I have been busy all day making arrangements. There are 60 loads, the Barotse do not lie carrier work, but there are plenty of slaves. Natives from Bihe carry their loads on the head or shoulder, but these must have it divided into 2 bundles and suspended from the ends of a stick, 6 feet long and laid across the shoulder.

By 10am next morning the loads are at the canal and the canoes are drawn up in readiness. Lewanika and some of his headmen walk with us to say goodbye and see us off and say to the carriers: “Remember, if you give any trouble, or cause naka’s (doctor’s) heart to be sore on the way you will have to settle with me when you return; so beware!”

By noon seven canoes, each manned by five paddlers, are ready and after much hand shaking and exchange of good wishes, the rowers seized their paddles and away we sped down the canal towards the Zambezi, my canoe taking the lead followed by Jack, a Barotse boy, who I engaged at Lealui as an interpreter. Then came the two Jamaicans and a white hunter, who having insulted Letia, the King’s son, was under orders to leave the country and whom I was giving a lift down the river, but had afterwards cause to regret having done so.

It was almost dark by the time we reached the marshy lakes that connect the canal to the Zambesi and our pilot lost his way amongst the tall reeds and we ran aground several times until at last we found the narrow opening. By now we were still 3 miles from Sefula mission station, it was pitch black and the mosquitoes attacked us unmercifully.

Most of the crew took shelter in a nearby village. Leaving four men to guard the loads I took Jack and waded through several hundred yards of water until the ground grew firmer and by 10pm we reached Sefula where Monsieur Coillard made us comfortable.

16 January. At daylight my men took possession of the huts built by the King’s people for Letia’s wedding. I was busy making bales of blankets, bought from Monsieur Coillard to pay the carriers. In this part and the next 800 miles a carrier does not think he's paid, however much calico he gets, unless there is a blanket with it.

I shall never forget the time spent on this station with the veteran missionary, Francis Coillard. If I have seen one mission in Africa that deserves the full sympathy and hearty support of christians at home more than another, it is this one.

Waddell and Monsieur Coillard and Christian converts

18 January. By 9am the canoes are loaded and every man in his place ready to start. A final farewell and we are off at full speed down the canal and by 11am had reached the Zambesi.

All the men stand to paddle, the steersman at the bow and four astern of the cargo, bending their bodies to each long but steady stroke and in perfect rhythm. Sitting on a mat exposed to the scorching sun would be very trying to one's patience but for the interest created by watching the crocodiles as they slide lazily from the banks into the water at our approach or looking at the numerous hippo's that infest the river, bobbing up every few hundred yards, extending their enormous jaws, snorting and blowing, often in dangerous proximity to our fragile bark, sometimes as many as 40 to 50 in a herd;[iv] but we shoot past, giving them as wide a berth as possible.

There is nothing remarkable in the scenery as we are still in the Barotse Valley and the banks are only from four to six feet high, while the vast grassy plains stretch out on either side with scarcely a bush to be seen, although now and again we notice a large tree standing solitary and alone, marking the grave of some ancestral chief. On getting opposite any of these, the boatmen ship their paddles, drop on their knees, clap their hands and raising their hands above their heads, shout “Yo sho” (shwilela) to these defunct chiefs - the gods of the Barotse.

Our expedition travelling down the Zambesi

We now reached Nalolo, the village of the queen, Magwai about 3pm. We pitched our camp in sight of her town, but by the time my tent was up, fever had me down, yet I had to struggle against my sickness and with an effort walked over to pay a formal call and salute her majesty, otherwise we should have no firewood. Excusing myself from my brief visit, I returned to camp and turned in as soon as I could.

Limamba, my boatswain, tries hard every evening to so time our progress that we shall halt at an old camp; but they are generally so very dirty and so infested with vermin that I invariably avoid them. He dislikes being thwarted and would like to pose as captain as at home he is a minor chief and wears round his neck the insignia of his rank - an omande shell. None but chiefs or those of royal blood are permitted to wear this distinguishing badge.

I shot several ducks, two spur-winged geese and a beautiful specimen of the great fish-eagle, the outstretched wings of which measured six feet seven inches from tip to tip… they live entirely on fish and from the overhanging branches they watch for their prey to come to the surface of the water, when like lightning they swoop down and seize it in their powerful talons, retiring into the bush to enjoy their meal. This bird sometimes secures fish up to 46 cm (18 inches) in length. When the capture is witnessed by the boatmen they make a bee-line in its direction and rob it of the prize.

In the evening we reached Senanga, the extreme end of the Barotse Valley and we camp at the edge of a forest. It is quite a relief to see trees again after the monotony of seven weeks on the unbroken expanse of grass and reeds. Here we must stop for a few days as part of my loads, which have come so far by water, must now be taken by carriers overland to Sesheke, which we hope to reach three weeks hence.

The prominent features of this camp are crocodiles and mosquitoes: the latter fill the air with a buzz like a hive of bees and their sting is little less severe; while out on the water at about fifty yards from where I sit, three huge crocodiles are floating like logs on the surface.

22 January. It has been raining heavily for most of the day. The headman of the overland detachment has arrived with his carriers. This is encouraging and certainly surprises me not a little—a happy contrast to my troubles with the West Coast natives. Serving out a little gunpowder, caps, lead and a few pieces of calico completes the arrangements and they are off; tomorrow, all being well, we do likewise.

On the 23rd we struck camp and pushed off again, the men pulling with plenty of vim after their few days’ rest. I noticed the high-water mark of the Zambesi by the debris deposited among the branches of some trees twelve feet above the present level and indicating the height it will possibly reach in another two months. The scenery is now completely changed; instead of the bald and uninteresting banks on either side, we have a variety of splendid trees with very few breaks.

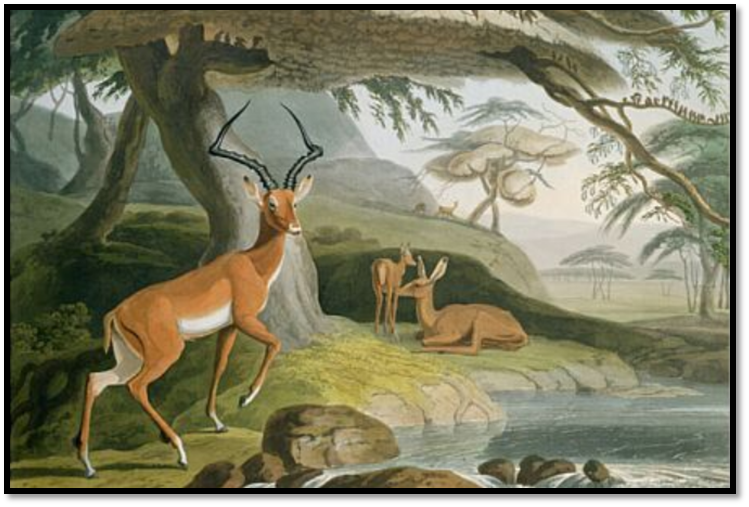

The placid water looks like a lake and the numerous islands, varying in size from a few feet square to many acres, are all richly clad in vegetation, the larger ones abounding in game. On one of these, called Beta, to our right and on the west bank, we camp for the night. I am simply charmed by my surroundings and who would not be? The chief interest, however, is centred on the three pots that are steaming over the fire, one containing rice, another corn meal dumplings and the third ribs of a Pallah buck shot about an hour ago within 300 yards of the camp.

Coloured aquatint engraved by Daniell Samuel (1775-1811) of Pallah antelope

The river spreading out to nearly a mile in width gives us a great deal of shallow water, twice my canoe was stuck fast on the top of stones - the first we have come across of any size, large or small in the last 600 miles. Now we would rather be without them, for being large boulders hidden under the water, which is dark at this season of the year, we are in constant danger of an upset. We reach Sioma in the afternoon, within a mile and a half of the falls of Gonya (now Ngonye or Sioma Falls) To avoid the latter, we have to get all the canoes taken from the water and dragged over land for a distance of some 7 km (4 miles) but I find that Lewanika has thoughtfully sent on a man to collect natives, so as to have no delay.

The transferring of the canoes past the falls is, after all, a very commonplace affair. They are not carried, but dragged along the ground by means of bark ropes and always have been since travelling by the river began, with not more than 12 men to each, and as to the hill, there is nothing imposing about it, being only five or six feet high.

Yesterday as the day cleared up, I got a few boys and with my photo apparatus trudged off to the falls of Gonya. After four hours on the rocks, alternately scorched by the sun and drenched by the rain, we retraced our steps, gratified beyond measure for the privilege of having been permitted to view the falls, cascades, and rapids of Gonya.

Gonya Falls, Zambesi river

The following day we proceeded with the loads to where the canoes were awaiting us below the falls. We got on the water again so that an hour after starting I ordered a halt and formed camp on a sandbank, about 100 yards below the confluence of the Lumbi. This river is over half a mile wide a little higher up its course, but here comes thundering down a narrow rocky gorge of not more than 50 yards as it enters the Zambezi.

Horseshoe falls of Gonya

27 January. The Barotse men do not know these waters well, so Johnston engages a local pilot. Three hours brought us to the Kari Rapids, where the waters were so turbulent and forbidding that we had to unload and carry the stuff past the most dangerous places. I have to reserve a portion of each day now for the purpose of hunting, so as to provide meat for our thirty-eight hungry men, the corn they carried with them being finished: but it would be an easy matter to feed five times as many here, as both banks of the river are simply teeming with game.

Zambesi boatmen with James Johnston

During the next few days we made but short runs, being frequently delayed in getting our dug-outs safely through the numerous rapids; but the scenery seems more beautiful than ever, the many clusters of wild date palms along the banks adding peculiar charm to the grandeur of the landscape.

On the 30th, while quietly gliding along in smooth water near the bank, I was aroused by a noise at first like distant thunder, but every second coming nearer and increasing to a terrific roar, like the sound of an approaching express train. I stopped and jumped ashore. It proved to be an immense herd of buffaloes tearing through the thicket within a dozen yards of where I stood, leaving a track behind them as though a regiment of heavy artillery had just gone by. We got out rifles and gave chase, but they outpaced us.

We got underway again, but in a few minutes arrived at the Ngambwe Falls. These falls are insignificant in themselves, being only five or six feet high. Both above and below them the riverbed is full of huge boulders which, with the rapidity of the current made the water so tumultuous that we were obliged to get out of the canoes and drag them by land for a good half mile, which occupied most of the afternoon. The day was gone and we camped.

I have been wearing for the past few weeks a pair of ‘veldt schoons’ native made-uppers of kudu hide, soles of buffalo and sewn with strips of antelope skin. They are very comfortable to the feet and are excellent for hunting in dry weather but get like a piece of wash-leather when wet...With the exception of two or three pairs of tennis-shoes, I have had no comfort in my footgear until I came across veldt schoons and I mean to stick to these as long as they will last - then make another pair.

Notes

[i] On 26 June 1890 King Lewanika signed the Lochner concession believing it was a treaty with the British government. In fact the concession ceded mineral rights to the British South Africa Company and put Barotseland under the company’s protection. Lewanika protested to London and to Queen Victoria that the BSAC agents had misrepresented the terms of the concession, but his protests were ignored fell until 1899 when the United Kingdom proclaimed Barotseland a protectorate and governed it as part of Barotseland-North-Western Rhodesia.

[ii] The first PMMS missionaries actually arrived in 1890 but were met with hostility by King Lewanika. They were forced to wait three years and endure a number of hardships before eventually being allowed entry to begin work among the Ila (Mashukulumbwe) peoples in the south of present day Zambia

[iii] Within a few months Letia took a second wife!

[iv] Usually a pod of hippos

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: