Great Zimbabwe – early written descriptions and photographs

Peter Garlake has argued that Great Zimbabwe’s ‘foreign origins’ that were put forward by Karl Mauch and contributed greatly to the ‘Zimbabwe controversy’ came originally from Swahili traders and Portuguese chroniclers who ignored the most obvious answer that the ruins were the work of local people.[i]

Even in 1891 Theodore Bent wrote: “We found but little depth of soil, very little debris and indications of a kaffir occupation of the place up to a very recent date and no remains like those we afterwards discovered in the fortress [Hill Complex]” Despite this the myth of ancient mythical / Biblical origins persisted.

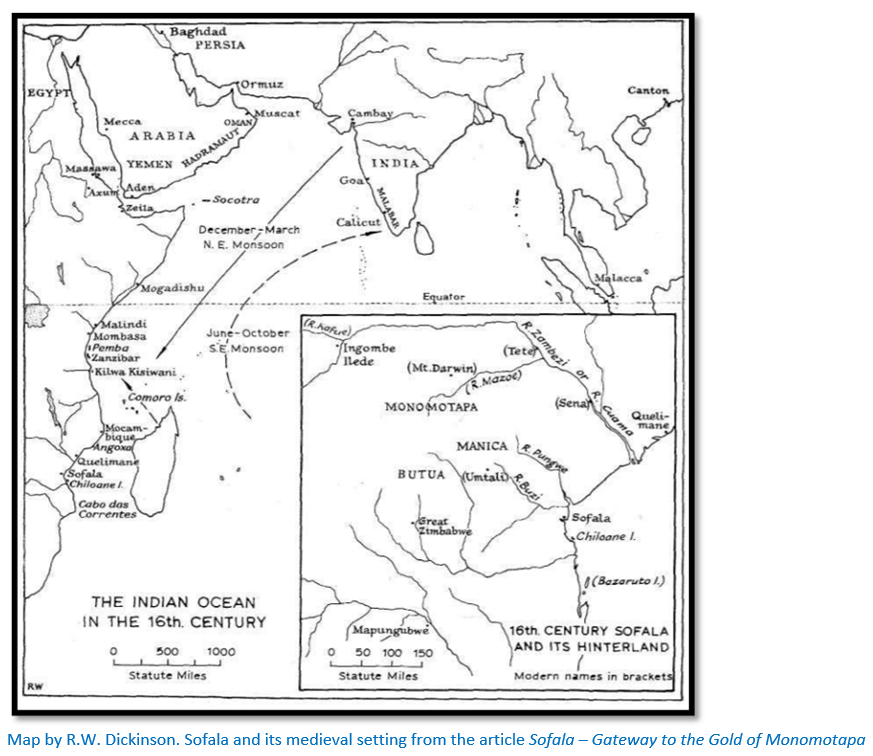

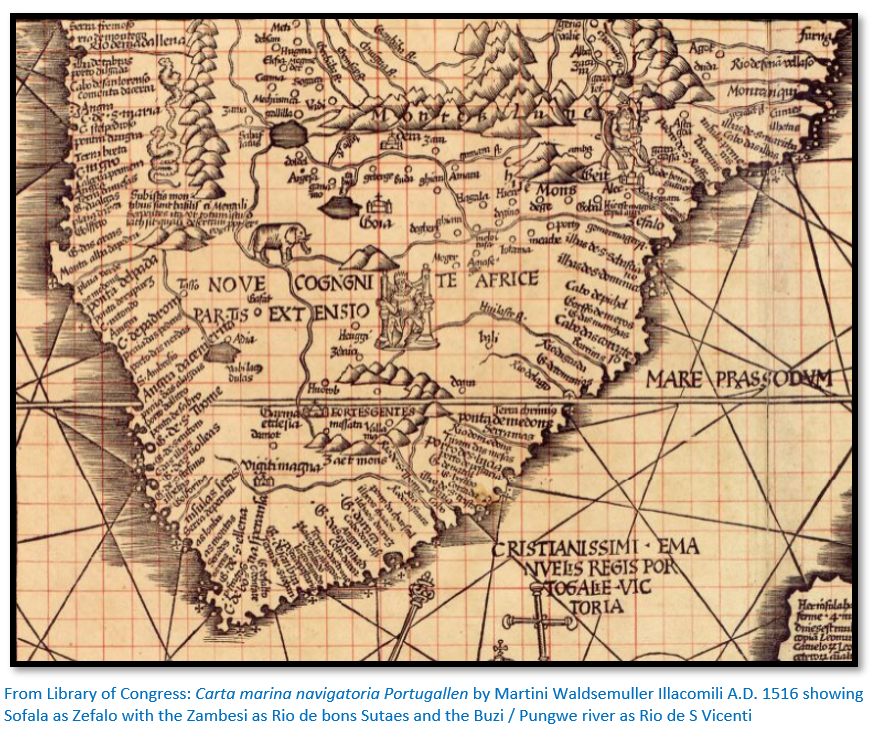

Earliest accounts are Portuguese, although they were not the first at Sofala, which had been settled by Swahili traders who thrived on the gold trade from the interior. The Buzi river connected Sofala to the internal gold market at Manica[ii] and from here to the goldfields of present-day Manicaland and the northern plateau of Mashonaland. However Portuguese reports provide the earliest written record of the interior of this part of Africa, but they are mostly about the Mutapa Empire, a loose confederation of states stretching across the plateau of northern Mashonaland.

The gold trade in the tenth Century dominated by the Somali trade network

During the tenth Century the gold trade at Sofala was dominated by Somali traders who came from Mogadishu and who used river-going dhows up the Buzi[iii] and Savé rivers to facilitate the movement of gold from the internal markets to the coast and across the Indian Ocean.

The Kilwa Sultanate seizes control in the twelfth Century

Portuguese chronicler Joao de Barros tells the fable behind the conquest: Mogadishu merchants had long kept Sofala a secret from their Kilwan rivals, who up until then rarely sailed beyond Cape Delgado. One day, a Kilwan fisherman was dragged by a fish he caught around Cape Delgado through the Mozambique Channel all the way down to the Sofala banks. When the fisherman arrived back in Kilwa he reported to the Sultan Suleiman Hassan what he had seen. Excited at the prospect of this gold trade the sultan loaded up a ship with cloth guided by the fisherman and sailed to Sofala. There in the 1180’s he offered the Mwenemutapa gold sellers a better deal and was allowed to erect a Kilwan factory and colony on the island and nudge the Swahili’s out.[iv]

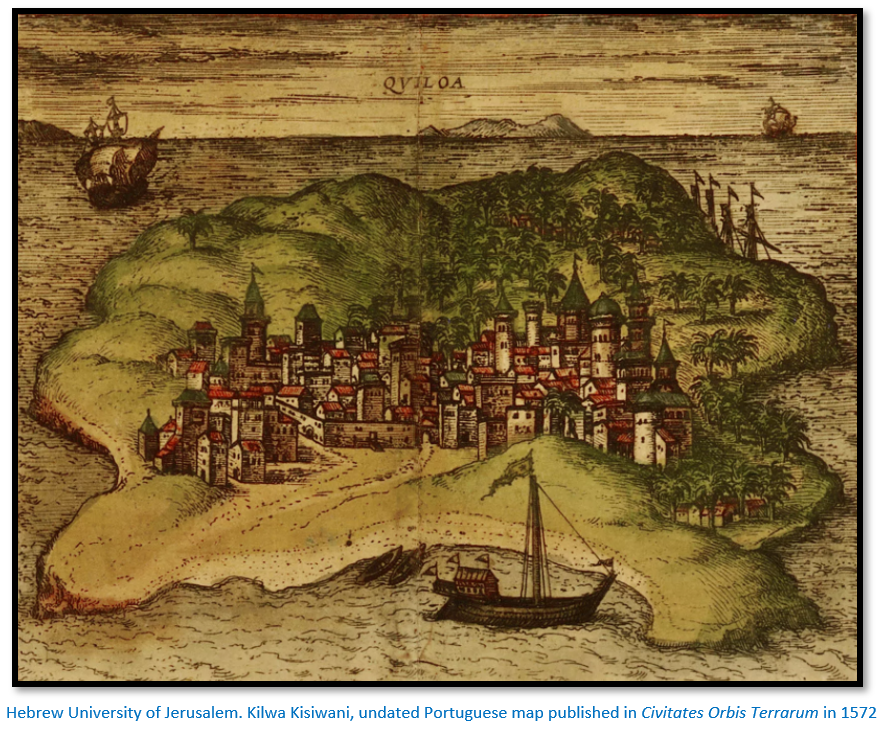

Sofala became part of the Kilwa Sultanate and the Swahili cultural sphere which flourished in the thirteenth to fifteenth Centuries along much of the East African shore. Today Kilwa is an Indian Ocean island off the southern coast of present-day Tanzania in eastern Africa.

Kilwa merchants traded gold, ivory, iron, and slaves from interior Africa ad imported goods included cloth and jewellery from India and porcelain and glass beads from China. Kilwa minted its own gold coins to facilitate international trade, one of which was excavated at Great Zimbabwe.

The Portuguese attempt to take control of the gold trade

In 1489 the Portuguese explorer and spy Pero da Covilha travelled overland disguised as an Arab merchant and was the first European known to have visited Sofala. His secret report to Lisbon identified Sofala as a centre of the gold trade although by this time the gold trade was a lot smaller than in previous centuries. In 1501 Sofala was scouted from the sea and its location determined by captain Sancho de Tovar. In 1502, Pedro Afonso de Aguiar (others say Vasco da Gama himself) led the first Portuguese ships into the harbour at Sofala.

The Portuguese intention was to capture the gold trade and their reports on the Kingdom of Mutapa, also referred to as the Mutapa Empire and Mwenemutapa are the earliest written accounts. However, their actual visits were limited to the present-day northern plateau of Mashonaland except for Antonio Fernandes described below and most of their reports are based on oral accounts which they took down from Swahili merchants still trading in the interior.

Diogo de Alcáçova letter in 1506 to the King of Portugal João III

Alcáçova wrote that in ‘Zunbanhy’ the capital of the Kingdom of Mutapa: “the houses of the King…were of stone and clay very large and on one level” and that they were part of the larger kingdom of Ucalanga (presumably Karanga, a southern Shona dialect spoken mainly in Masvingo and Midlands provinces of Zimbabwe.

Antonio Fernandes reports are dictated at Sofala in 1511 but with no references to Great Zimbabwe

Fernandes was illiterate and gave an account of the places he personally visited to the clerk Gaspar Veloso at Sofala saying that: “Embire…a fortress of the King of Menomotapa is now made of stone…without mortar.” Hugh Tracey believes from his writings that Fernandes used the river system to penetrate the interior[v] and this makes good sense.

Tracey believed that Fernandes directions indicate that the route to the goldmines ran towards the watershed of the northern river systems flowing into the Zambesi (called the Cuama by the Portuguese) and that the goldmines themselves lay on the northern side of the watershed.

Although the Buzi river is a much more direct and shorter route to the feira at Manica where gold was traded Tracey writes that Fernandes implies: “that the approach to this gold-mining region would best be made via the ‘river of Quitengue’ actually the Savé river which “flows into the sea sixteen leagues[vi] from the bar of Sofala.”

This southern route may have been recommended by Fernandes’ on the grounds that the Revue river, a major tributary of the Buzi river, was controlled by a hostile chief Inyamunda[vii] and it was safer, though longer in distance. It appears that the route along the Zambesi river (Cuama) was only contemplated in 1516 after Fernandes’ third journey to Mutapa when a later Captain of Sofala, Joao Vaz d’Almada reported that Fernandes had reported another river, the Cuama which flowed into the Indian Ocean forty leagues north of Sofala.[viii]

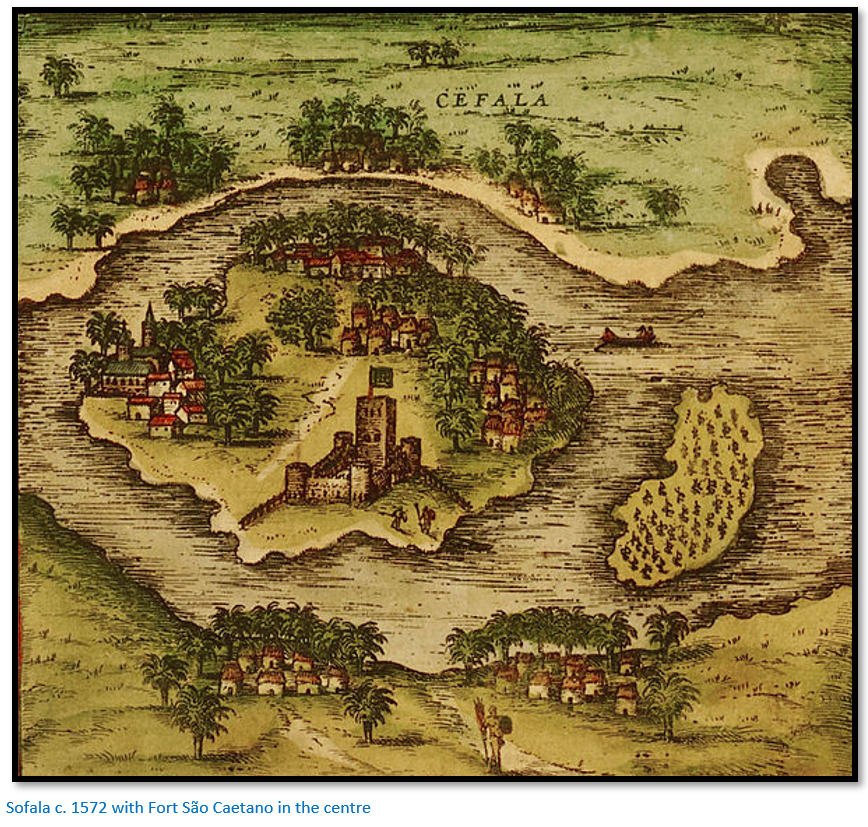

Little is known about Antonio Fernandes himself other than that he was listed in 1506 as working on Fort São Caetano as a carpenter and member of the garrison, in 1510 as a degradado (literally: exiled) and with subsequent entries after 1515 as ‘carpenter and interpreter’ presumably as reward for undertaking his journeys into the interior. In 1516 the Captain of Sofala, Joao Vaz d’Almada reports that Fernandes: “had already been to Benomotapa where he was held in great esteem, had been an effective peace-maker between tribal factions and was shortly to be given further responsible assignments.”[ix]

Although some sources state that Portuguese merchants and soldiers including Antonio Fernandes in 1511 visited Great Zimbabwe there is no evidence of that.[x] Tracey states that Fernandes appears to have walked about 56 kms (35 miles) south of Great Zimbabwe and he would surely have commented on such an impressive building had he seen it.[xi] Far more likely that any visits were made by Swahili merchants or Vashambadzi, local middle men or the offspring of Portuguese traders and local women.

Fernandes appears to have made three journeys into present-day Zimbabwe; his journeys in 1514 and 1515 were traced by Tracey onto a modern map. Eric Axelson’s translation of the report written by the clerk Gaspar Veloso at Sofala is too long for this article but in October 1514 the Afonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese Governor of India writes in a letter: “The officials of Sofala wrote me that they had received news of the man they had sent to discover that city of Benomotapa whence the gold comes and I believe that they will have given a detailed account of this deed to your Highness there” and the Sofala Captain Joao Vaz d’Almada states in another report to the King of Portugal on 25 June 1516: “…one Antonio Fernandes, who is from that time, who has already been to Benomotapa and has so much credit in all those lands that they worship him like a god.”[xii]

Duarte Barbosa in 1514

This third Portuguese reference describes a great town ‘Zimbaoche’ which he notes “pertains to the heathen” and their King Benemotapa.[xiii]

Vicente Pegado, Captain of the Portuguese Garrison of Sofala report from 1531

Pegado described Zimbabwe thus: “Among the gold mines of the inland plains between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers there is a fortress built of stones of marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them.... This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of stone and the absence of mortar, and one of them is a tower more than 12 fathoms [22 metres] high. The natives of the country call these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court.”

João de Barros writings Décadas da Ásia which appeared from 1552

The Décadas da Ásia ("Decades of Asia") was a history of the Portuguese in India, Asia and southeast Africa with the first edition appearing in 1552, the second Decade came out in 1553 and the third in 1563, but de Barros died before publishing the fourth Decade which was completed by Damiao de Gois.

His description of Great Zimbabwe was probably from Swahili traders who had visited the area and described them to Vicente Pegado who left Sofala in 1538 and whose reports were read and quoted by Barros. This is surmised because some of the Barros’ information was out of date, for instance Butua and Torwa were no longer Mutapa vassals by 1500.[xiv] These traders said the stone buildings were locally call Symbaoe, which meant "royal court."

“There are other mines in a district called Toroa, which by another name is known as the kingdom of Butua, which is ruled by a prince called Burrom, a vassal of Benomotapa, which land adjoins that aforesaid consisting of vast plains, and these mines are the most ancient known in the country, and they are all in the plain, in the midst of which there is a square fortress, masonry within and without, built of stones of marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them. The wall is more than twenty-five spans in width and the height is not so great considering the width. Above the door of this edifice is an inscription, which some Moorish merchants, learned men, who went thither, could not read, neither could they tell what the character might be. This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of the stone and the absence of mortar, and one of them is a tower more than twelve fathoms high.

The natives of the country call all these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court, for every place where the Benomotapa may be is so called; and they say that being royal property all the Kings other dwellings have this name. It is guarded by a nobleman who has charge of it after the manner of a chief alcaide, and they called this officer Symbacayo, as we should say keeper of the Symbaoe: and there are always some of Benomotapa’s wives therein, of whom the Symbacayo takes care. When, and by whom, these edifices were raised , as the people of the land are ignorant of the art of writing, there is no record, but they say they are the work of the devil, for in comparison with their power and knowledge it does not seem possible to them that they should be the work of man. Some members who saw it, to whom the Vicente Pegado, who was captain of Sofala, showed our fortress there and the work of the windows and arches, that they might compare it with the stonework of the said edifice, said that they could not be compared with it for smoothness and perfection. The distance of this edifice from Sofala in a direct Line to the West is 170 leagues, or thereabouts, and it is between 20° and 21° south latitude.[xv] There are no ancient or modern buildings in those parts, the people being barbarians and all the houses of wood.

In the opinion of the Moors who saw it, it is very ancient, and was built there to keep possession of the mines, which are very old, and no gold has been extracted from them for years, because of the wars. Considering the situation and the fashion of the edifice, so far in the interior, and which the Moors confess was not raised by them, from its antiquity and the ignorance of the characters of the inscription above the door, we may suppose that this is the region which Ptolemy cause Agysymba, where he made his meridional calculations; for the name of the edifice and that of the officer who guards it has some resemblance to that name, and one may be a corruption of the other.

Considering the facts of the matter, it would seem that some prince who had possession of the mines ordered it to be built as a sign thereof, which he afterwards lost in the course of time, and through their being so remote from his kingdom; and as these edifices are very similar to some which are found in the land of Prester John, at a place called Acaxumo, which was the municipal city of the Queen of Sheba, which Ptolemy calls Axuma, it would seem that the Prince who was lord of that state also owned these mines, and therefore ordered these edifices to be raised there.”[xvi]

Peter Garlake believes the general description of the buildings and the conical tower; the stone construction materials all correspond quite closely with Great Zimbabwe and therefore despite the differences – such as the distance from Sofala – it is reasonable to assume that these descriptions of important stone buildings were evidence that Swahili traders had visited Great Zimbabwe.

Duarte Lopez account of 1591 related by the Italian Filippo Pigafetta

“It is said by these certain ones [the Muslim traders] that from these regions the gold was brought by sea which served for Solomon’s Temple at Jerusalem.”[xvii]

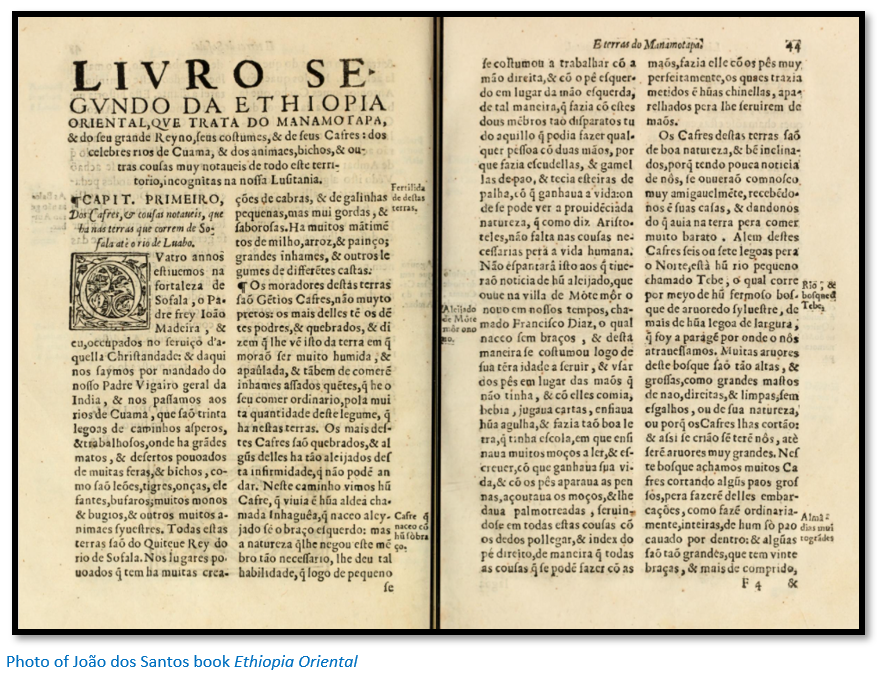

João dos Santos descriptions of Great Zimbabwe in his Ethiopia Oriental published in 1609

João dos Santos was a Portuguese Dominican missionary in Africa and then India. He was sent in 1586 to Sofala and then to Tete on the Zambesi river. From there he spent two years in the Quirimbas Islands which lie in the Indian Ocean off north eastern Mozambique, close to Pemba and then back to Sofala. He left Mozambique in 1597 for Portuguese India where he spent the rest of his life.

His accounts are based on personal experience and for the first time, not third party accounts and therefore are not jumbled by time and repetition. He is describing the northern plateau of Mashonaland in the vicinity of Mt Fura (Mt Darwin) “On the summit of this mountain some fragments of old walls and ancient ruins of stone and mortar are still standing, which clearly show that once there were houses here and strong dwellings, which are not to be found in Kaffraria, as even the King’s palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with straw. The natives of these lands, especially some aged Moors, assert that they have a tradition from their ancestors that these houses were anciently a factory of the Queen of Sheba, and that from this place a great quantity of gold was brought to her, it being conveyed down the rivers of Cuama to the Indian Ocean…Others say these are the ruins of the factory of Solomon, where he had his factors who procured a great quantity of gold from these lands…not deciding this question, I state that the mountain of Fura or Afura may be the region of Ophir, whence gold was brought to Jerusalem, by which some credit might be given to the statement that these houses were the factory of Solomon.”[xviii]

Diogo de Couto writes in the Ninth Décadas da Ásia in 1616

Parts of dos Santo’s account are included as: “It is conjectured…that the Queen of Sheba…obtained gold at these places…even at the present day at the markets of Massapa [the Portuguese feira near Mt Fura] and Nabertura[xix] there are great stone in edifices which she commanded to be built for herself, which are called Symbaoe by the Kaffirs and which are like strong bulwarks” and he added: “These edifices the Kaffirs always consider to be the means by which Monomotapa obtained dominion over all Kaffraria.”

The belief that the builders of Great Zimbabwe were not indigenous

Garlake thinks the Swahili traders were so overawed by Great Zimbabwe’s splendour and aged look – they also believed there was an inscription that must be the work of literate people – that they would have discounted any claims that local Karanga people might have made. Dos Santos had also assumed, perhaps illogically, that because the Karanga did not build in stone, therefore they never did.

De Barros’ ‘Moorish merchants’ admitted they knew nothing about the builders and Dos Santos’ ‘aged Moors’ admitted the same when they named Solomon or the Queen of Sheba. Garlake says in their struggle against the Portuguese they would have used historical connections to establish their rights to the gold trade if they could, but they had none.

Accordingly the Portuguese completely ruled out any possibility of indigenous or Swahili origins for Great Zimbabwe and for all the Symbaoe they came across. Their views were coloured by memories of the great lost Christian kingdom of Prester John and the gold upon which its wealth was founded and a very hazy and exaggerated idea of how far Ethiopia extended down Africa.[xx] The Portuguese Governor of Goa suggested an expedition to ‘Zimbaboe’ “because there is much foundation for the belief that the land is Ophir.”

Vasco da Gama's companion Tome Lopes was one of the first to connect Ophir with present-day Zimbabwe, although we know that Great Zimbabwe dates long after Solomon is said to have lived. The identification of Ophir with Sofala in Mozambique was mentioned by Milton in Paradise Lost (11:399-401) among many other works of literature and science. These claims would be repeated by most of the foremost geographers for the next two centuries: Pigafetta (1591) Purchas (1614) Speed (1627) Ogilby (1670) Dapper (1668) and d’Anville (1727) amongst others.

The Bible as the most precise historical account in the seventeenth century

It is perhaps inevitable that early geographers turned towards the Bible as a well-known source and the tales of Solomon and his Phoenician partner, Hiram, King of Tyre[xxi]: “And King Solomon made a navy of ships…and Hiram sent in the Navy his servants, shipmen that had knowledge of the sea, with the servants of Solomon. And they came to Ophir, and fetched from thence gold, four hundred and twenty talents and put it to King Solomon…and the Navy also…brought in from Ophir great plenty of almug trees and precious stones. And the King made of the almug trees pillars for the house of the Lord, and for the King’s house…And all King Solomon's drinking vessels were gold…silver was nothing accounted of in the days of Solomon. For the King had at sea a navy of Tarshish with the navy of Hiram: once in three years came the navy of Tarshish, bringing gold and silver, ivory and apes, and peacocks. So King Solomon exceeded all the Kings of the earth for riches and wisdom.”[xxii]

The Missionary Alexander Merensky and Hugh Walmsley perpetuate the Ophir legend

The Dutch sent several abortive expeditions to the north from the Cape in search of the mines and temples of Solomon without any success.

For the Boers with their deep faith in the Bible the stories of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba created a feeling that the Transvaal might be on the edge of these fabled Biblical lands that had long been sought after. The most knowledgeable and enthusiastic believer that: “in the country northeast and east of Moselekatze [i.e. in Mashonaland] the ancient Ophir of Solomon is to be found and that in the times of the Ptolemies Egyptian trade penetrated to our coasts” was the Reverend Alexander Merensky, a German missionary who had worked in the eastern Transvaal since 1859.

Merensky’s ideas had inspired H.M. Walmsley to write and publish in 1869 his book called The ruined cities of Zululand; a half-mad account of a journey to reach rumoured cities of gold in the far African interior during which they are threatened by menacing and savage inland tribes. A short piece illustrates the overall silliness: “The white chiefs are not traders, but like gold,” said the savage, after a prolonged stare. “They seek some fallen huts, formerly made by their white fathers?” asked he, speaking in the Zulu tongue. “Achmet Ben Arif spoke truly when he told you so, Umhleswa,” was the reply. “The white chiefs saw the fallen house at Sofala. In the mountains at Gorongoza are caves; the traders of the Zambesi built the house, the worshippers of the white man’s God lived at Gorongoza. There are no other remains of them.” “And the stone tablets on the mountain?” eagerly asked the missionary. The lips of the savage parted, showing the sharp filed teeth. “They are the graves of those who served the white man’s god.”

Rider Haggard stirs the imagination for African exploration

The prospect of finding the Biblical Ophir in southeast Africa was excited even further by Rider Haggard’s best-selling novels King Solomon’s Mine published in 1885 and She.[xxiii] Combined with Mauch’s wild claims for the origin of Great Zimbabwe these all confirmed to nineteenth Century minds that Solomon had built Great Zimbabwe.

The books also started a new literary genre of which involves a lost world and usually a cache of treasure trove and would inspire Edgar Rice Burroughs The Land That Time Forgot, Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, Rudyard Kipling's The Man Who Would Be King and H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness. Edgar Rice Burroughs in The Return of Tarzan introduces the lost city of Opar, very similar in sound to the Ophir of King Solomon's Mines.[xxiv]

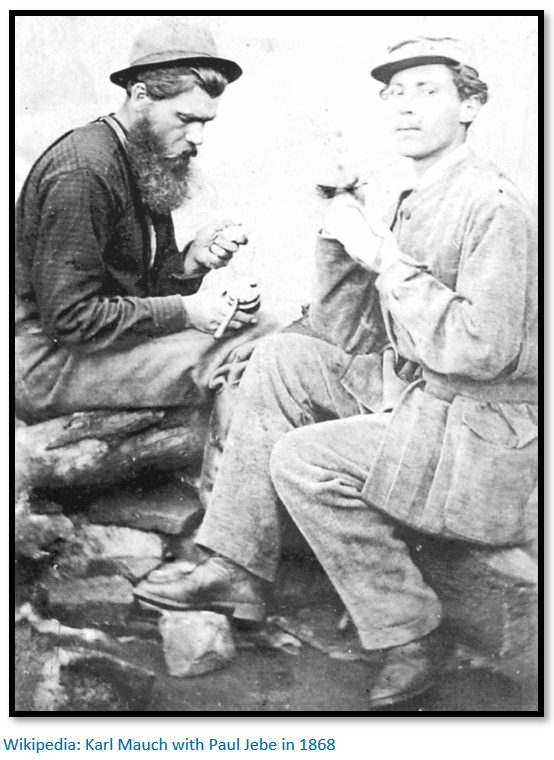

Karl Mauch seeks the Old Monomotapa or Ophir

In 1868 Merensky and Mauch met, with Merensky telling the young geologist and fellow German all he knew about the Ophir legend and the ruins he believed to lie across the Limpopo river. Mauch set off in May 1871 to explore: “the most valuable and important and hitherto most mysterious part of Africa…the old Monomotapa or Ophir.”

Much’s journey and examination of Great Zimbabwe is investigated in the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com By end August 1871 he had reached Adam Renders, a hunter and trader who had abandoned his wife and four children in the Transvaal and was living with the daughter of a local chief. Renders knew: “of the presence of quite large ruins which could never have been built by blacks” and he and Mauch made three visits to the ruins of Great Zimbabwe during Mauch’s nine month stay.

What Mauch saw and wrote about and sketched is described in the above article but the local Karanga were newcomers to the area following the great upheavals of the Mfecane and told Mauch that: “the walls were built at a time when the stones were still very soft, otherwise it would have been impossible for the whites who built the walls to form them into a square shape.”[xxv]

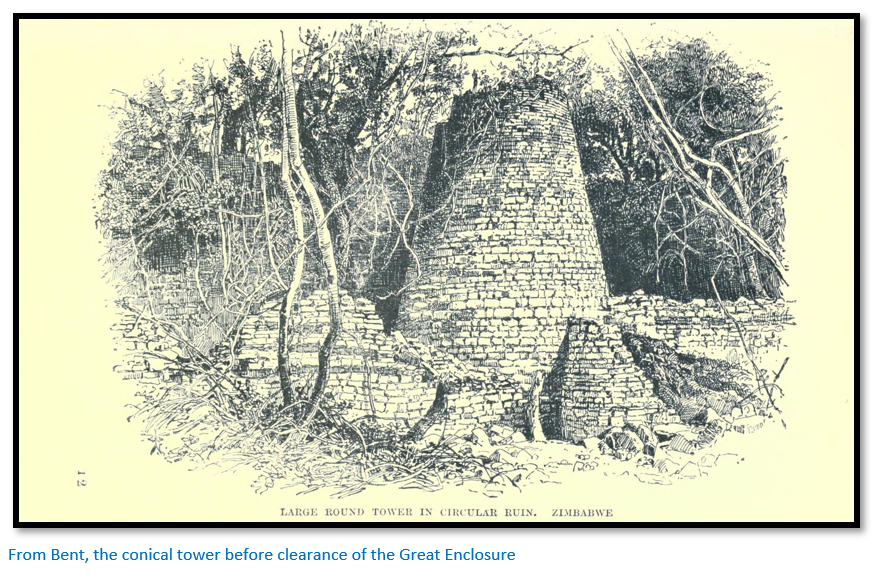

Mauch wrote to his German patron August Petermann on 12 September 1871: "Zimbaoe, known from Portuguese writings, lies 11 English miles to the east of here and represents a mighty fortress, consisting of two parts of which one, on a hill of about 400 feet with very large boulders is separated by a narrow little valley from the second, which stands on a slight rise. Up till now it has not been possible for me to make a plan of both of them as the walls, in places still 30 feet high, are completely covered, and as dangerous nettles ill repay any attempt to creep through them. The walls are built, without any mortar, of hewn granite slabs more or less of the size of our bricks, and are, except at three points, very well preserved in a "Rondeau" on the plain of a diameter of about 150 yards. In the southern part of this there stands a tower built up to about 30 feet, at the base of a cylindrical, at the upper half of a conical shape, and in a wall in front of it there are some absolutely black stones which make me suspect that this is a burial site."[xxvi]

On his final visit to the ruins, due to local suspicions Mauch was only allowed three visits to Great Zimbabwe in nine months, he cut some wood from a collapsed lintel and found it unaffected by insects, reddish, scented and with a ‘great similarity’ to the wood of his pencil and this confirmed his theories: “It can be taken as fact that the wood which we obtained actually is cedar wood[xxvii] and from this that it cannot come from anywhere else but from the Lebanon. Furthermore only the Phoenicians could have brought it here: further Solomon used a lot of cedar wood for the building of the temple and of his palaces; further, including here the visit of the Queen of Sheba and considering Zimbabwe or Zimbaoe or Symbaoe written in Arabic (of Hebrew I understand nothing) one gets as a result that the great woman who built the rondeau could have been none other than the Queen of Sheba.”

Thus Karl Mauch the first European to describe Great Zimbabwe to the outside world perpetuated the Muslim tales that had reached the Portuguese over three centuries before.[xxviii] Mauch’s German patron Dr A. Petermann predicted that the goldfields described by Mauch: “are identical with the Ophir of the Bible and with the places from which Solomon obtained his wealth in gold.”[xxix]

Great Zimbabwe as a symbol of the rightness and justice of colonization

Garlake writes that to those who believed that Great Zimbabwe was Phoenician in origin gave an emotional identification with the British occupation of Mashonaland. “What the great British Empire is to the nineteenth century, Phoenicia was to the distant ages, when Solomon’s temple was built in Jerusalem: a tiny country perched on the edge of a continent that led all nations in trade and technology and whose intrepid seamen had voyaged to the farthest sea and whose citizens had colonized the entire known world.”[xxx]

The British South Africa Company, gold and the land of Ophir

The BSA Company did nothing to quench the connection between Great Zimbabwe, the rumours of gold which had been confirmed by Mauch at Tati and Hartley Hills and ancient civilisations which did so much to fire the imaginations of the young men who clamoured to join the Pioneer Column…over 2,000 applications were received for 190 vacancies. Indeed the real inducement for most was not their pay but the promise of 15 gold claims and the right to 3,000 acres (1,214 hectares) of land.

‘Skipper’ Hoste account of a visit to Great Zimbabwe whilst the Pioneer Column rested at Fort Victorian now Masvingo

“On August 15th, after getting the necessary leave, a party consisting of Captain P. Forbes (Police) Canon Balfour (Chaplain to the Police) Captain E. Burnett (Pioneers) Lieutenant Ellerton Fry (Pioneers) Trooper F. Langerman (Pioneers) and Messrs. J. Beaumann, F. E. Harman and H. Denny belonging to some of the prospecting parties that accompanied the column; and I started off at dawn to visit the ruins of Zimbabwe which had been discovered forty years before by Carl Mauch. We took a couple of native guides with us, a pack horse, and two pack donkeys to carry grub, blankets, etc.

After we had crossed a couple of ranges of hills the guides pointed to a kopje some seven miles off and said: "Zimbabwe." Then after crossing three rather bad swamps, in one of which the horses went in up to their girths, we reached the kopje, on top of which we could see large masses of masonry; there were also a lot of native huts mixed up with them. As soon as we reached the foot of the kopje a crowd of natives turned up, armed in various ways; some with bows and arrows and some with assegais. They told us to stop where we were and began fitting arrows to their bows in a most threatening manner, so we palavered with them for a bit, and eventually after we had given the chief a blanket as a present, they became more amiable and condescended to listen to us.

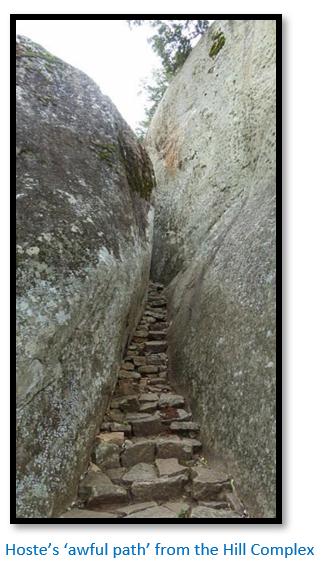

Their first proposal was that if we wanted to see the ruins we should be led up to them blindfolded. This was promptly rejected on our side. Then after more talk they said that they would show us the ruins, but we mustn't bring up our native guides with us. To this we agreed and off we went up the kopje where we found ruinous remains of what looked to us like a citadel, [i.e. the Hill Complex] in the enclosures of which the natives were living. They had evidently utilized the old building to the utmost, pulling down the walls wherever it suited them and using the stones for building new and very round walls in all sorts of places never contemplated by the original architect.

We wandered about the place for a bit and then a slab-sided young savage who was showing us around and who I believe was the son of the chief, led us off by an awful path down the back of the hill to the plain. There we found ourselves among the ruinous remains of what had apparently been a town many centuries before. After passing through them we came to a large circular building [i.e. the Great Enclosure] that we had seen from the path as we came down the kopje.

Our guides for some reason would not let us go in at the entrance but made no objection to our climbing through a gap in the wall. The inside of the place was a perfect jungle of trees, bushes and creepers. As most people have read far better descriptions of the place than I could possibly write, I won't attempt to describe it further than by saying that of all the ruins in Rhodesia, and there are many of them, it is far and away the most marvellous.

Fry, who was our official photographer, got his camera going to the great alarm of the natives who watched him in fear and trembling, expecting an explosion every moment. We in the meantime wandered about the place. We camped there that night, and the next morning after an early breakfast saddled up and returned to the laager where we arrived in the forenoon.”[xxxi]

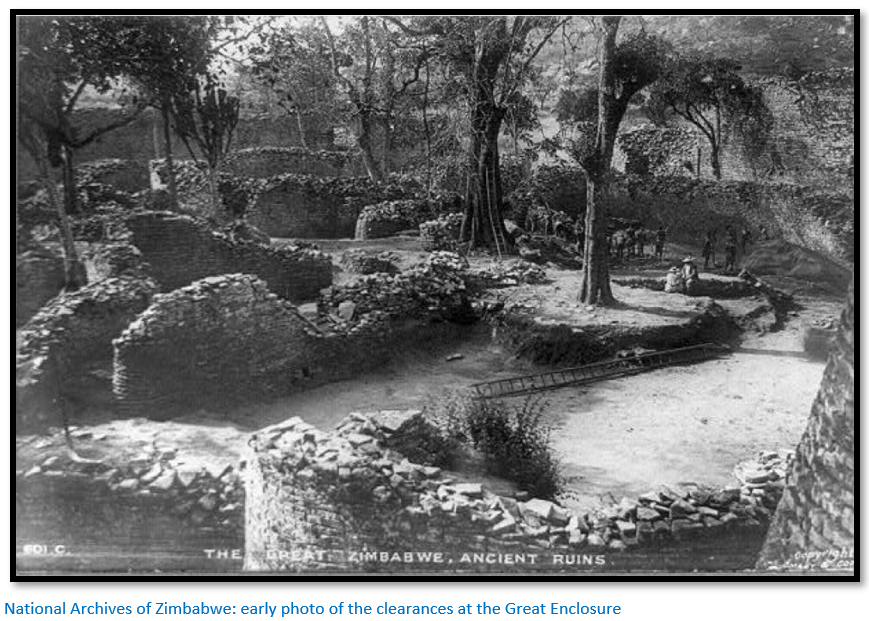

Theodore Bent - the first investigation of Great Zimbabwe

Within a year of the occupation of Mashonaland the British South Africa Company sponsored the first investigation with the support of the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the man chosen for the work was J. Theodore Bent, an amateur archaeologist and antiquarian who travelled widely in Arabia, Greece and Asia Minor, with his wife and a surveyor Robert M.W. Swan.

He had experience of the archaeology of the Mediterranean and the Phoenicians, but said before even starting: “Now of course it is a great temptation to talk of Phoenician ruins when there is anything like gold to be found in connection with them, but from my own personal experience of Phoenician ruins I cannot say that [the Great Zimbabwe ruins] bear the slightest resemblance whatsoever.” After being at Great Zimbabwe for some months in 1891 he went even further: “the names of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba were on everybody’s lips and have become so distasteful to us that we never expect to hear them again without an involuntary shudder.”[xxxii]

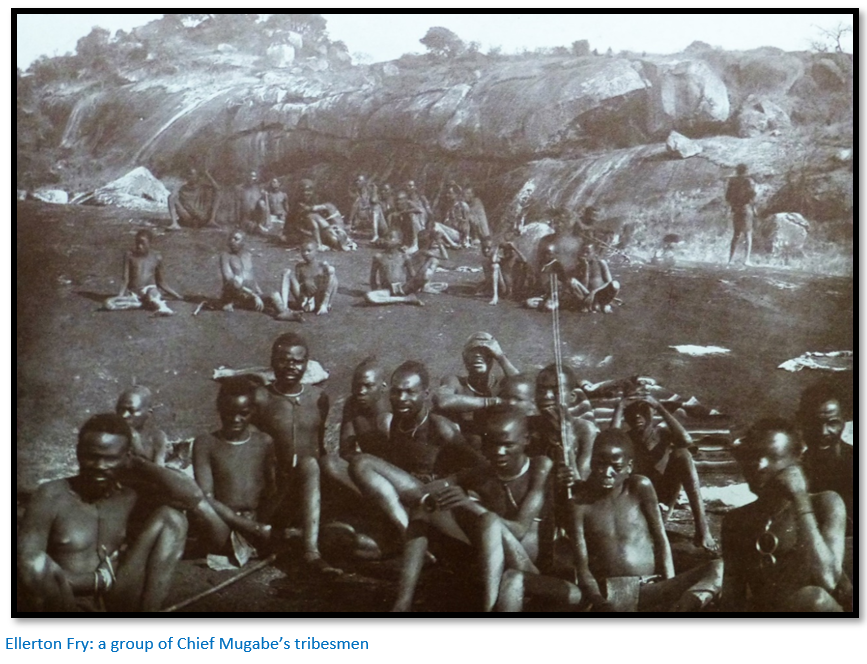

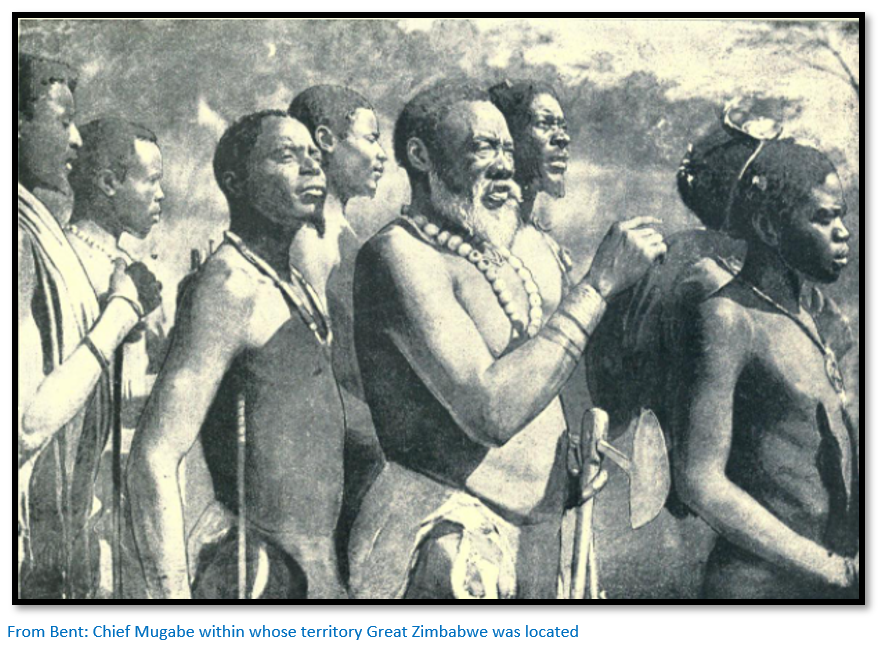

Bent says Chief Mugabe’s kraal was six miles away and they saw little of him, but his brother Ikomo was the headman and lived in the Hill Complex and they saw much more of him.

In June 1891 excavations started near the conical tower inside the Great Enclosure but the results were disappointing from a foreign origins point of view and Bent concluded to his local guide C.C. Meredith: “I have not much faith in the antiquity of these ruins, I think they are native…everything we have so far is native.” So work was abandoned in this area and began in the Eastern Enclosure of the Hill Complex.

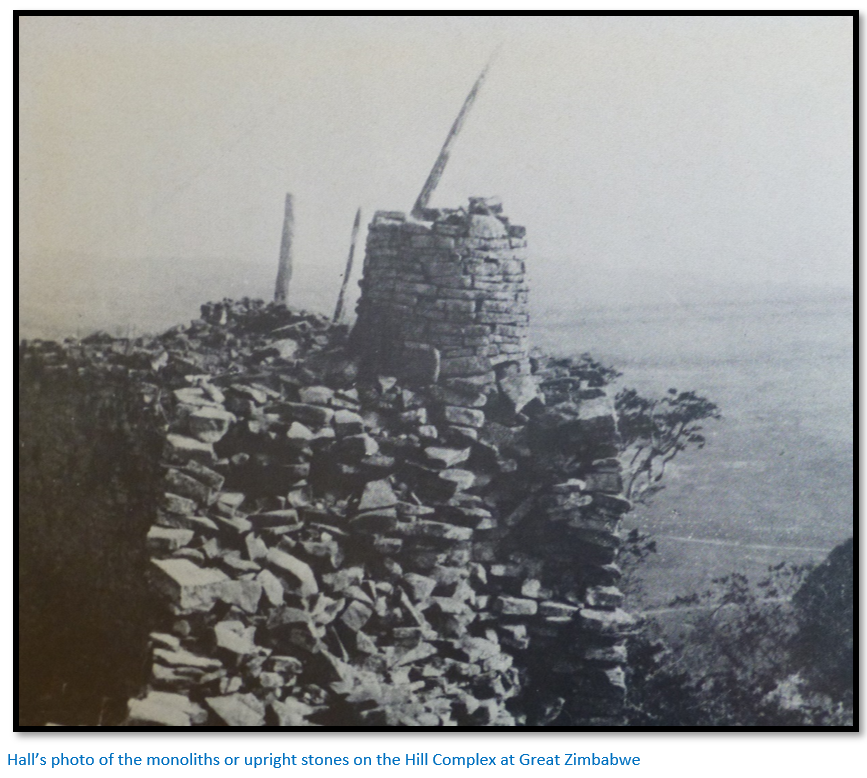

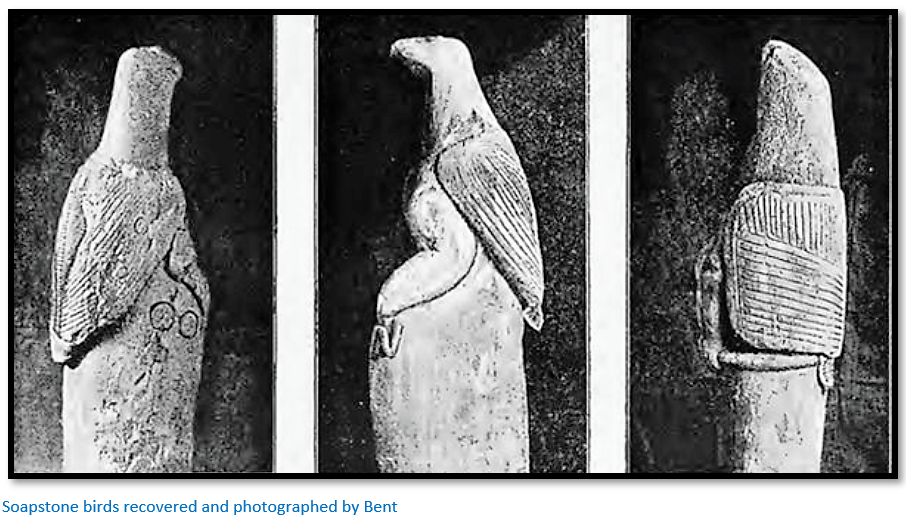

Great quantities of domestic objects were found; broken pottery sherds and spindle whorls, iron, bronze and copper spearheads, arrowheads, axes, adzes and hoes and the remains of gold working equipment such as tuyeres and crucibles. Most were indistinguishable from Karanga articles still being used at the time although some unidentified items were found including soapstone birds on carved monoliths, flat soapstone dishes and some small carved cylindersthat looked like phalli (i.e. an erect penis) and an ingot mould. The only identifiable and dateable objects were pieces of Arabian, Persian and Chinese ceramics and glass which were four to five centuries old.

Nothing like these soapstone items had been found before and Bent assumed they were clues to the builders of Great Zimbabwe and looked for parallels. The soapstone birds on monoliths resembled objects from Assyria, the patterns on the phalli and monoliths resembled similar Phoenician styles, a similar mould had been found in Cornwall and was thought to be Phoenician.

However despite the obvious conclusion of local and recent origins Theodore Bent managed to produce a hotch-potch of interpretations – the birds were gods and goddesses, the disc patterns indicated sun worship, the monoliths and cylinders indicated nature-worship and the conical tower was depicted on a Byblos coin.

Bent’s lame and contradictory conclusion? “A prehistoric race built the ruins…which eventually became influenced and perhaps absorbed in the…organizations of the Semite…a northern race coming from Arabia…closely akin to the Phoenician and Egyptian…and eventually developing into the more civilised races of the ancient world.”[xxxiii]

He was satisfied that: “the ruins and the things in them are not in any way connected with any known African race.”

Swan believed the ruins had been laid out with careful planning based on pi, a ratio he thought had been raised to almost occult status. He theorised altars had been set at the centre of arcs of the main walls and their use was combined with doorways, monoliths and hilltop boulders to form sighting lines orientated on certain stars and solstices.

Bent’s book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland being a record of excavation and exploration in 1891 was the first comprehensive description of Great Zimbabwe. Fontein writes that “However sceptical he might have been of the King Solomon and Queen of Sheba myths, his conviction that ancient foreign builders were responsible [for constructing Great Zimbabwe] was clearly based on the prevailing racial attitudes of the time.”[xxxiv]

Sir John Willoughby rummages in the ruins in 1892

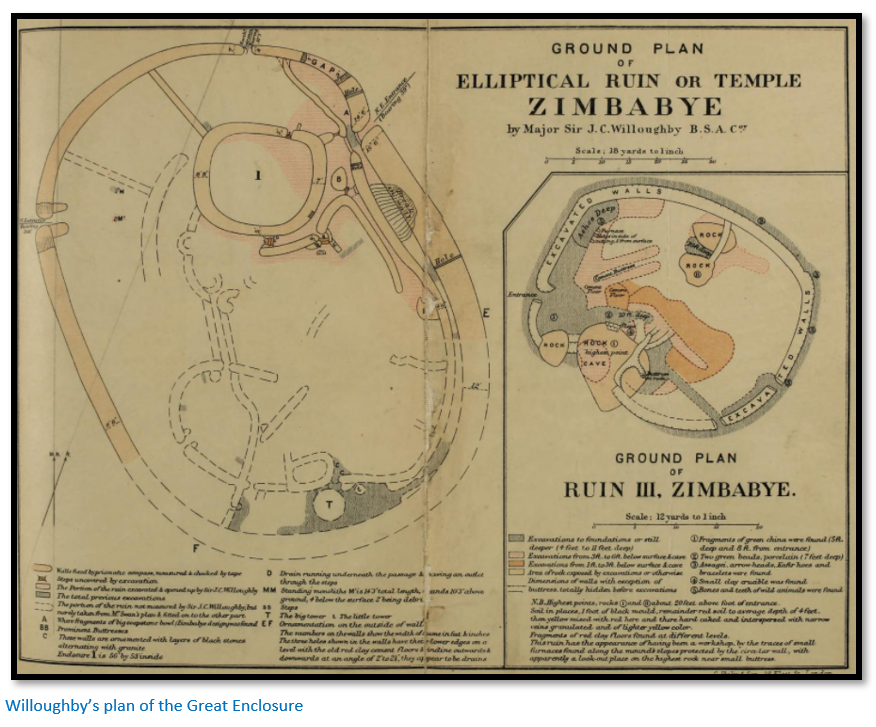

Willoughby’s digging took place in the three of the Valley ruins and inside the north-west entrance of the Great Enclosure.

Soon after his arrival on 10 November 1892 he noted that the Mugabe tribespeople were being driven out of their former homes by newcomers who had recently arrived in the area and were under the protection of Charimbira, a local important Chief.[xxxv] Fighting had taken place under the walls of Great Zimbabwe a day or two before Willoughby’s arrival and two of Mugabe’s tribesmen were killed.

In return for negotiating a peace between them Willoughby managed to obtain native labourers for his excavations. When the fifty labourers failed to arrive on site he told Chief Mugabe that he would be forced to employ other workmen, whereupon his labour force presented itself next day promising to work for a month on payment of a blanket apiece and their daily food.

Prior to carrying out any work elsewhere Willoughby explored some of the caves in the Hill Complex discovering iron implements and arrowheads, but what interested him most were: “numerous fragments of clay crucibles containing small beads of gold and some of these were distinguished by a greenish glaze on the outside.”

Willoughby lists five pages of archaeological finds from Great Zimbabwe but as Garlake states: “He had no archaeological pretensions and worked with the sole object of excavating…as thoroughly and rapidly as possible and without that caution which the expectation of an ‘experts’ report demanded.”[xxxvii]

Although he threw some doubts on Bent and Swan's measurements, he did not give any alternatives theories as to Great Zimbabwe origins.

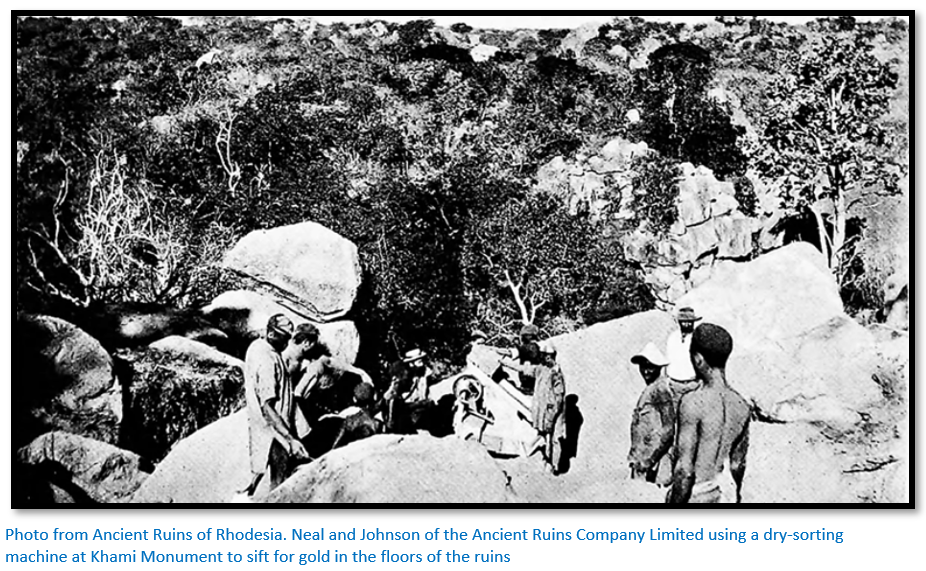

Ancient Ruins Company Ltd

F.R. Burnham wrote of a trip in 1893 to Great Zimbabwe which he made with his wife and little son. “In this picturesque country a traveller from the New World has strange thoughts as he stands on the granite tombs and looks down on the great walls and labyrinths of stone set without mortar by some energetic people of a past so misty that there exists neither legend nor tradition of them. We searched room after room, examined with interest the doors of rock that slid into place [?] and speculated about the curious conical sun tower. After a thorough exploration, I took a gold pan and worked over some of the debris near a little spruit (stream) which flowed through the ruins and in a few hours I washed out more than a hundred small gold beads and other ornaments of the ancient inhabitants. My wife and little boy became intensely interested in this panning, so I left them to continue the search for treasure while I went hunting.”

Little more was heard about ancient ruins until after the Second Anglo-Boer War when the previously noted associations between gold and ruins led to the formation in 1895 of a company named the Ancient Ruins Company Ltd which dug into around seventy-five ruins and completely destroyed the archaeological record they contained.

A great quantity of gold ornaments – over 600 ounces (19 kgs) was dug up by Burnham and Pearl Ingram at Danangombe and Mundie ruins. It was agreed that the BSA Company would receive 20% of all finds and that “Mr Rhodes on behalf of the BSA Company would have the first right of purchasing any discoveries. The ruins at Zimbabye were excluded for the present at Mr Rhodes’ express desire.”[xxxvi]

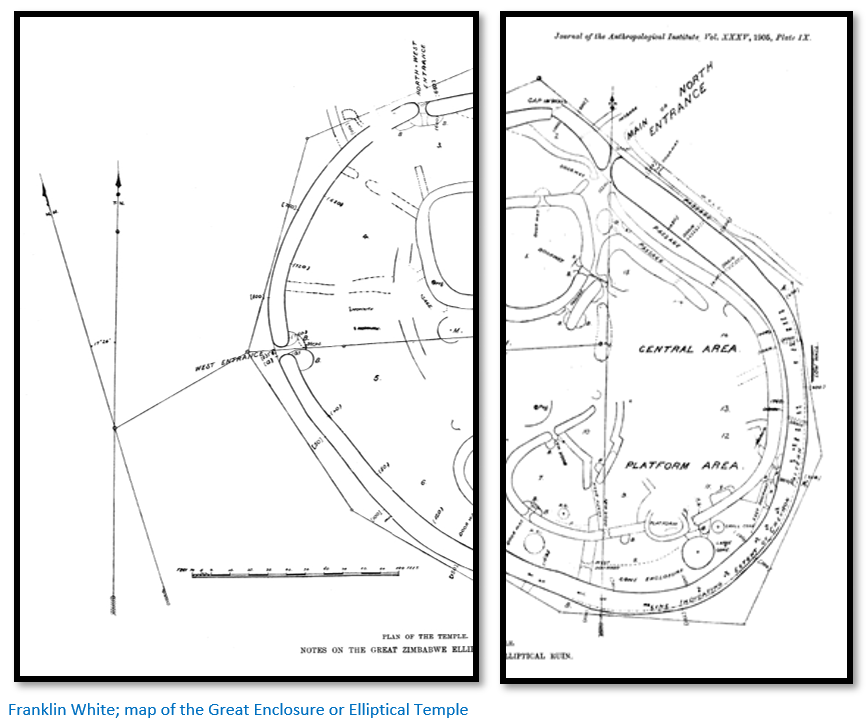

Franklin White

White visited Great Zimbabwe after F.P. Mennell, curator of the Rhodesia Museum stated that the generally accepted measurements of the conical tower by Swan were incorrect. In October 1903 White made a new and complete survey of the Great Enclosure – then called the Elliptical Temple.

He had some difficulty measuring over heaps of stones and ruined walls which resulted in inconsistencies. For example, White made the maximum length of the Great Enclosure as 292 feet. Willoughby made 294 feet; Bent and Swan made 286.5 feet. The respective widths were: 220 feet, 216 feet and 235 feet.

Bent and Swan’s cubit theory was thrown out altogether by the facts. The circumference of the small tower does not measure 10 cubits or 17.17 feet, but 21.5 feet. Neither does the circumference nor the diameter of the large conical tower correspond to their cubit measurement. The distance between the centres of the doorways were stated to be 107.8 feet (62.82 cubits) but are in fact 112.5 feet.

Bent and Swan’s statements that certain points of the decorated wall are illuminated by the rising sun on certain dates and that the chevron pattern are of Egyptian origin were not borne out by White’s survey and offered no proof that the ancient builders were Semitic or sun and nature worshippers.

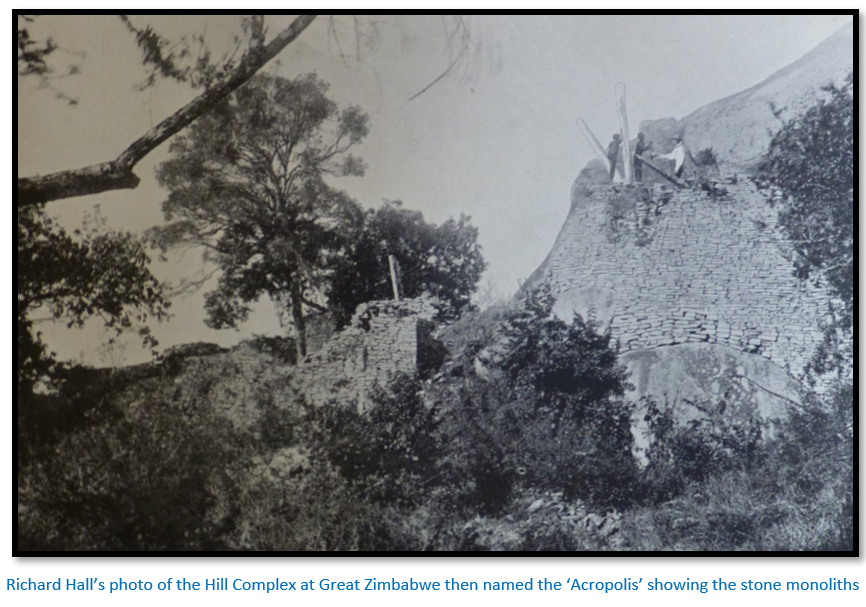

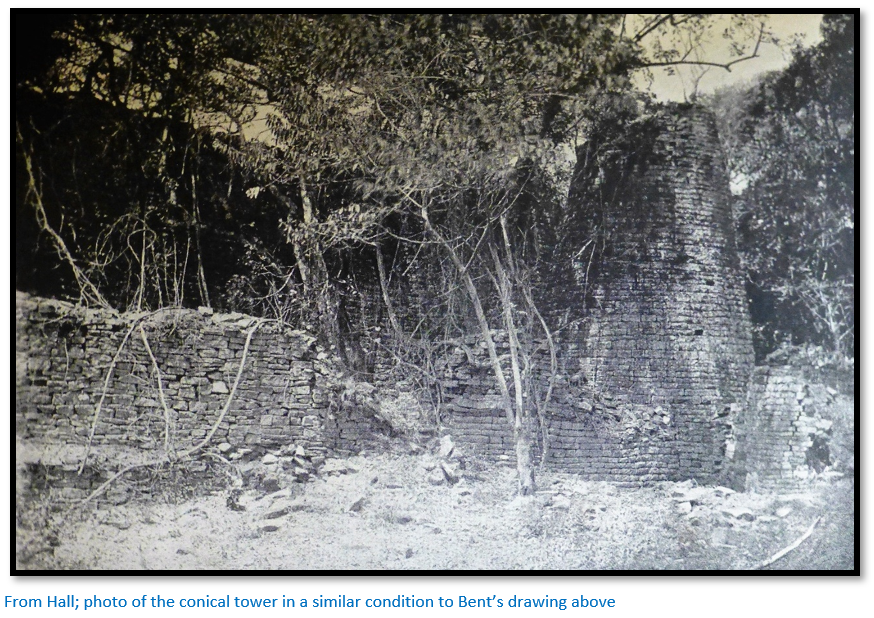

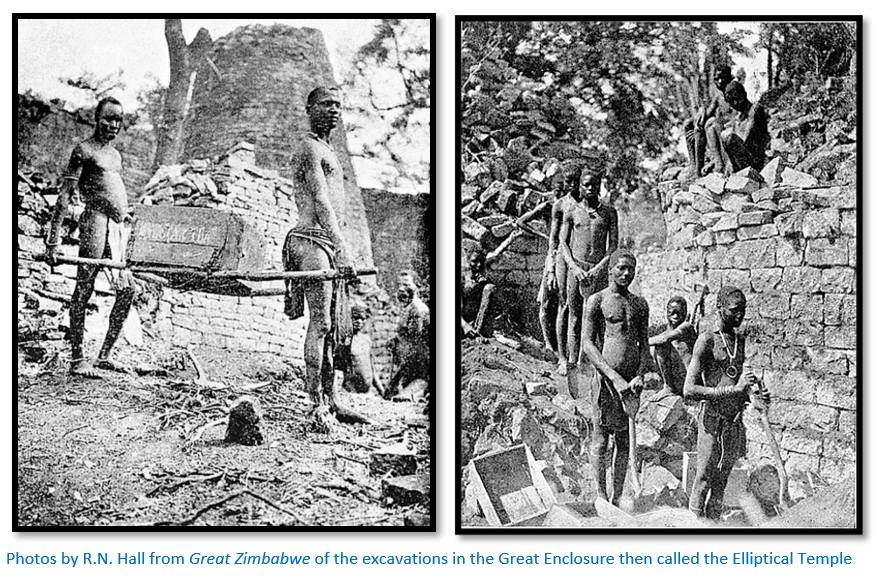

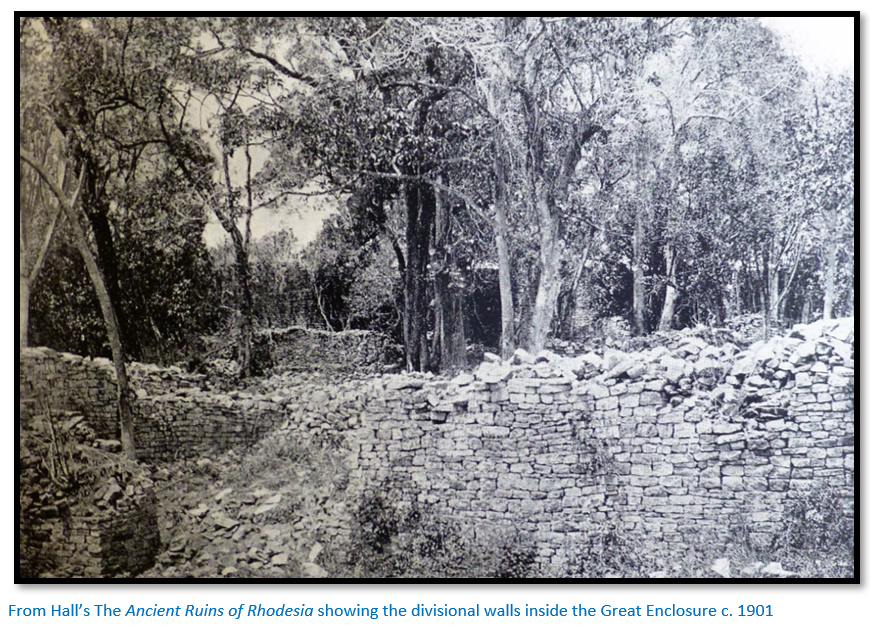

Richard N. Hall

Richard Nicklin Hall was appointed as Curator of Great Zimbabwe saying that he wished to free the site “from the filth and decadence of the Kaffir occupation” and removed anything that might link the site with its African cultural significance. His extensive clearances of the Great Enclosure between 1902 – 1904 probably were the most destructive of all the excavations at Great Zimbabwe and described by a visiting archaeologist as “reckless blundering… worse than anything I have ever seen” before he was dismissed from his post.

His main aim seems to have been to clear the undergrowth and level the floors in order to make it more accessible to visitors and as result the first five feet (1.5 metres) of topsoil was removed and from his own writings it appears that a considerable amount of gold was recovered as well as carved soapstone objects, iron tools, local and imported Chinese glazed pottery. Summers notes that Hall admitted to recovering over £4,000 of gold.

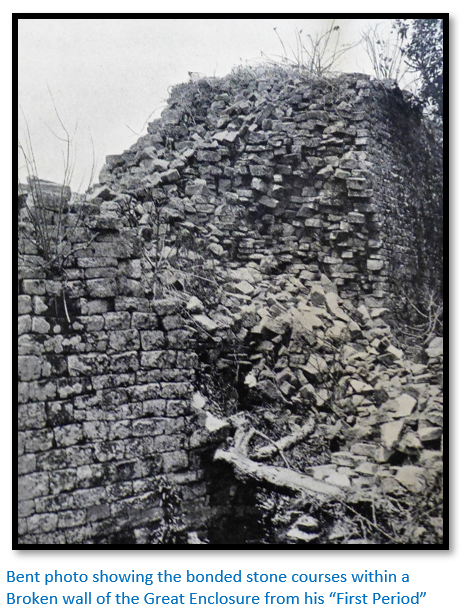

R.N. Hall and W.G. Neal’s book The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia (Monomotapae Imperium) was published in 1902 and describes almost every ruin found and ransacked by Neal in Matabeleland and the rest of the country. Hall attempted to assign types of style to the various ruins assuming they must represent separate periods and therefore peoples.

He assigned the first stylistic period to the Sabaeans dated 2000 – 1100 BC; the next to the Phoenicians lasting until the Christian era, the third to an ill-defined transitional period and the fourth as a “decadent period to bastard races.”

His second book Great Zimbabwe published in 1905 covers the two year period he was curator and elaborates on the architectural style definitions found in his earlier book in which he assumes a progressive degeneration from the finely dressed walls of the Great Enclosure to the poorly coursed walls of the Hill Complex and Valley Ruins all the time holding to his early theory that they were built by different people over an extended period of time.

Cultural appropriation of Great Zimbabwe

Whilst this article discusses mostly the physical excavations that took place at Great Zimbabwe what should not be forgotten is the cultural appropriation that also took place. When the earliest European visitors came to Great Zimbabwe the Mugabe clan occupied parts of the Hill Complex and the area was grazed by their cattle, used for hunting and gathering fruits and thatching grass. As time went on they were increasingly distanced and alienated from the site.[xxxviii]

Ninth German Inner Africa Research Expedition

Leo Frobenius led twelve expeditions to Africa between 1904 – 1935; the ninth between 1928 – 1930 visited present-day Zimbabwe and most of the Southern African countries with specific aims of researching southern Erythrean cultures, ancient mines and ‘Bushmen’ paintings (i.e. San rockart)

Frobenius, a German ethnologist and archaeologist, maintained that a culture he named ‘Erythrean’ was responsible for the construction of Great Zimbabwe. He came up with a theory that a white civilization of Mediterranean origin must have existed in Africa prior to the arrival of European colonisers to have been responsible for the mines and dry-stone buildings within Zimbabwe.[xxxix] This was not so far from the myths put out by Karl Mauch more than thirty years previously.

Archaeological excavations that confirmed Great Zimbabwe’s local and recent indigenous origins

The British archaeologist David Randall-MacIver was the first in 1906 to assert that the architecture of Great Zimbabwe showed exclusive African origin and influence. He greatly criticized Hall’s work and this combined with a habit of talking down to public audiences did not endear him to early audiences and was the beginning of the ‘Zimbabwe controversy’ which raged thereafter.

He was followed by Gertrude Caton-Thompson who examined the Great Zimbabwe site in 1929 and agreed with Randall-MacIver as to its local origins.

In the 1950’s Roger Summers, Keith Robinson and Anthony Whitty independently excavated at Great Zimbabwe and confirmed its indigenous origins and finally in 1973 Peter Garlake agreed that it origins were indigenous. However the pressures from government was such that in the 1970’s both Summers and Garlake left the country for upholding their scientific views.

Other historians and archaeologists who have carried out valuable research at Great Zimbabwe include D.N. Beach, S. Chirikure P. Hubbard, T.N. Huffman, G. Mahachi, M. Manyanga, E. Matenga, G.M. Mazarire, I. Pikirayi and D. Tangri. Apologies to those I may have omitted.

References

E.E. Burke (Ed) F.O. Bernhard. Discoverer of Simbaye: The Story of Karl Mauch, 1837-75. Part 1. Rhodesiana Publication No 21, December 1969

S.T. Carroll. Solomonic Legend: The Muslims and the Great Zimbabwe. The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol 21, No 2 (1988) P233-247

J. Fontein. The Silence of Great Zimbabwe; Contested Landscapes and the Power of Heritage. Routledge, 2016

R.W. Dickinson. Sofala – Gateway to the Gold of Monomotapa. Rhodesiana Publication No. 19, December 1968

P.S. Garlake. Great Zimbabwe. Thames and Hudson, 1973

H.F. Hoste (Ed) N.S. Davies. Gold Fever. Pioneer Head, Salisbury, 1977

G.C. Mazarire (2013): Carl Mauch and Some Karanga Chiefs Around Great Zimbabwe 1871–1872: Re-Considering the Evidence, South African Historical Journal, DOI:10.1080/02582473.2013.768290

H. Tracey. Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer. Rhodesiana Publication No 19. December 1968

F. White. Notes on the Great Zimbabwe Elliptical Temple. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol 35 (Jan - June 1905) P39-47

J.C. Willoughby. A narrative of further excavations at Zimbabye (Mashonaland) George Philip and Son, 1893

Notes

[i] Great Zimbabwe, P54

[ii] The Buzi river used to enter the sea at Sofala, but its mouth has now moved 30 kms (19 miles) north to Nova Lusitânia

[iii] Tracey states the Buzi river was navigable by canoe for 97–113 kms (60-70 miles) from the coast

[iv] Wikipedia footnote in article on Sofala

[v] Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer, P2

[vi] The Savé river flows into the Indian Ocean 96 kms south of Sofala which is close to his 89 kms (16 leagues)

[vii] Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer, P16

[viii] Sofala to the Zambesi mouth in the north is 334 kms, rather longer than 222 kms (40 leagues) suggested in the Portuguese accounts

[ix] Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer, P7

[xi] Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer, P24

[xii] Antonio Fernandes Rhodesia’s First Pioneer, P8

[xiii] Solomonic Legend, P241

[xiv] Great Zimbabwe, P53

[xv] 170 leagues are equal to 587 miles; Great Zimbabwe is 250 miles due west of Sofala. However the latitude is correct with Great Zimbabwe at 20°16´

[xvi] Decade I, Book X, Chap 1 in Theal, VI, pp267-8

[xvii] Solomonic Legend, P241

[xviii] Great Zimbabwe, P53

[xix] This name does not seem to relate to any of the identifies Portuguese feiras

[xx] Great Zimbabwe, P55

[xxi] Tyre is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world in Lebanon

[xxii] I Kings, 10:22

[xxiii] Solomonic Legend, P236

[xxiv] Wikipedia entry on King Solomon’s Mines

[xxv] Great Zimbabwe, P63

[xxvi] Discoverer of Simbaye

[xxvii] Actually Spirostachys africana or tambootie whose wood is reddish-brown with a fragrant, spicy smell and a prized furniture wood

[xxviii] Great Zimbabwe, P64

[xxix] Solomonic Legend, P238

[xxx] Great Zimbabwe, P65-66

[xxxi] Gold Fever, P61-2

[xxxii] Great Zimbabwe, P66

[xxxiii] Ibid, P68

[xxxiv] The Silence of Great Zimbabwe, P7

[xxxv] Gerald Mazarire has written a very interesting article worth reading: : Carl Mauch and Some Karanga Chiefs Around Great Zimbabwe 1871–1872: Re-Considering the Evidence

[xxxvi] Great Zimbabwe, P70

[xxxvii] Ibid, P69

[xxxviii] Ibid, P6

[xxxix] Wikipedia – Leo Frobenius