Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield

In 1890 only three gold-fields were well-known. The Mazowe Valley, the Northern, near LoMagondi’s (north of modern Chinhoyi and on the Angwa River) and the Mupfure River (formerly the Umfuli) or Hartley gold-fields. According to William “Curio” Harvey Brown the Hartley goldfield had the reputation as the richest.

Many Pioneers made directly for Hartley Hills as soon as the Pioneer Column was disbanded in the hope they would peg a rich gold claim and make their fortune. The BSA Company issued licences at a shilling each, entitling prospectors to peg a block of ten claims (fifteen if they were a Pioneer) each 45 metres (150 feet) in length by 120 metres (400 feet) wide.

Brown took one of Frank Johnson’s ox-wagons to the diggings and along the way they killed a large black rhinoceros which the whole party helped to skin along with much joking about how once they had made their fortunes they would all journey to see the skin and skeleton exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World Fair.

Old Fort Hartley played a prominent part in the first Chimurenga, or Mashona Rebellion; initially twelve prospectors moved into the fort with ample supplies and ammunition on the 24th April 1896, and were under constant attack from the 18th June until the 22nd July 1896 when they were rescued by a relief party led by Capt. the Hon. C. J. White.

This was the longest actual siege of the Matabele / Mashona uprisings of 1896-7 or Umvukela, or First Chimurenga and the defenders were very vulnerable, particularly when collecting water from the Umfuli River (now the Mupfure) almost 1.7 kilometres away. It is a bit surprising that Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe did not commit more of his military resources to seizing Old Fort Hartley, rather than just besieging it. In the following year on 17 March 1897 Chief Mashayamombe committed 300-400 of his men on an attack on Fort Martin which had been established close to his kraal in a battle that lasted three hours, so he had the manpower.

Easy access from Harare to an historic site with associations with Henry Hartley, Thomas Baines, early gold mining and the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga.

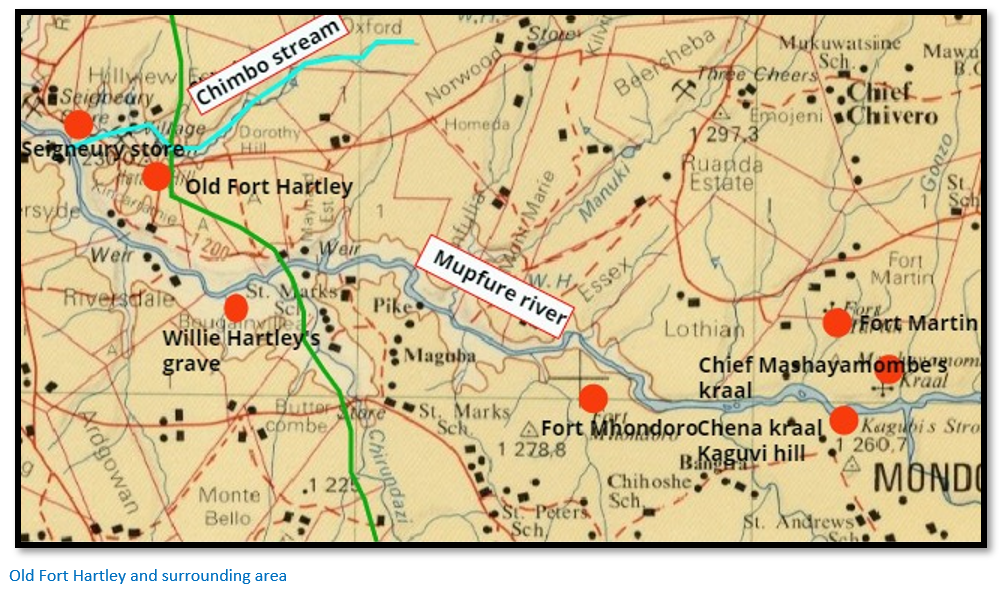

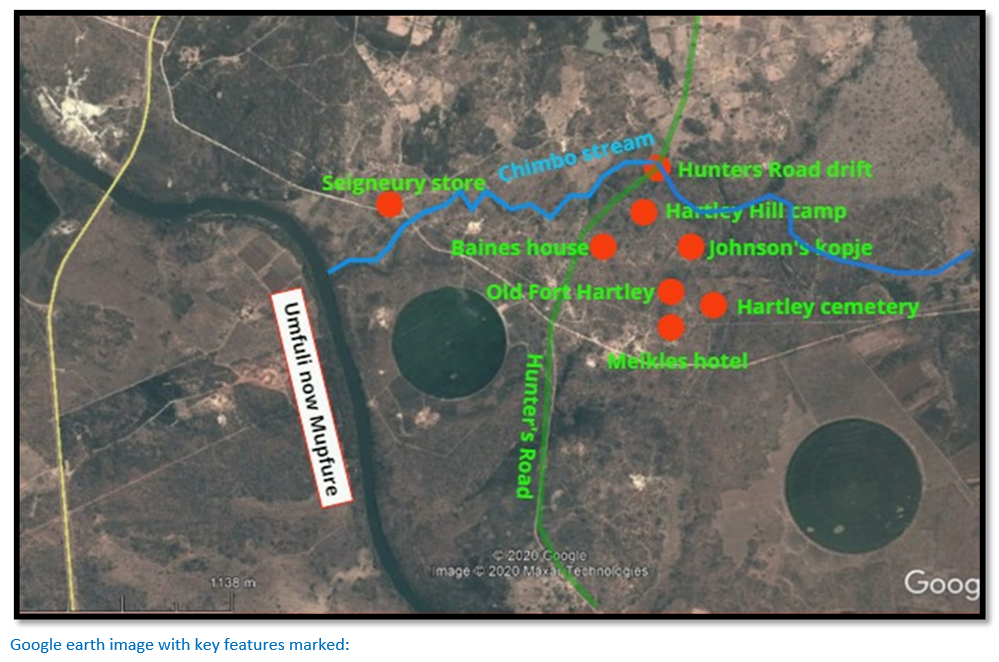

Hartley town on the A5 national road is now named Chegutu. The original Hartley Hill goldfields are east of the junction of the Mupfure River (formerly the Umfuli) and the Chimbo River (sometimes marked Zimbo) The area is easily reached from the main Harare Bulawayo A5 National road 71 KM from Harare, by turning left off the National road at the roundabout, south toward Ngezi Mine. At 7.2 KM continue past Chengeta Safari Lodge turnoff on the left and at 15.73 KM reach Seigneury Road intersection. Turn left onto the gravel road, 17.54 KM go to the left of the Seigneury store, 17.69 KM cross the Chimbo River, 18.00 KM pass the stamp mill on your left, 18.62 KM stay on main gravel road, pass old gold diggings on your right, 19.11 KM a farm track turns left for Fort Hill. (i.e. 3.3 KM from the tar turn-off) 19.27 KM take right-hand fork, 19.62 KM park car and the fort is on the summit of the kopje to your left. Johnson’s kopje is to your right. 350 metres northwest of Johnson’s kopje are the two peaks of Hartley Hill mining camp next to the Chimbo Stream. See the Google earth image for the layout of the original site.

GPS reference for Fort Hill: 18⁰12′05.81″S 30⁰23′46.11″E

GPS reference for Johnson’s kopje: 18⁰12′01.16″S 30⁰23′47.41″E

GPS reference for the cemetery: 18⁰12′12.55″S 30⁰23′45.19″E

GPS reference for Hartley Hills mining camp: 18⁰11′53.32″S 30⁰23′40.59″E

GPS reference for the Hunters Road drift across the Chimbo Stream: 18⁰11′46.61″S 30⁰23′41.70″E

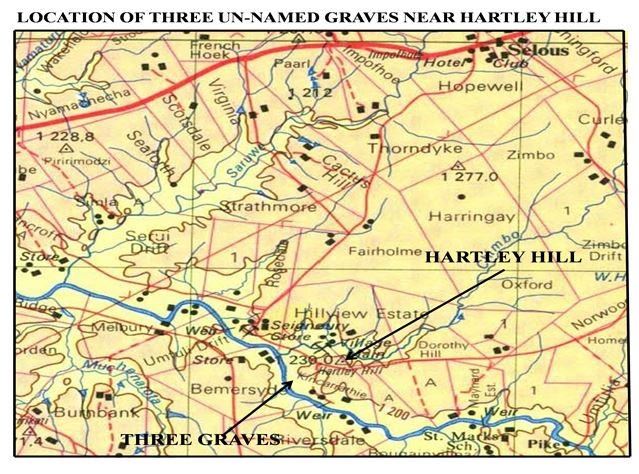

Below is a general map at 1:250,000 scale showing the principal places of interest referred to in the following articles and how they physically relate to each other:

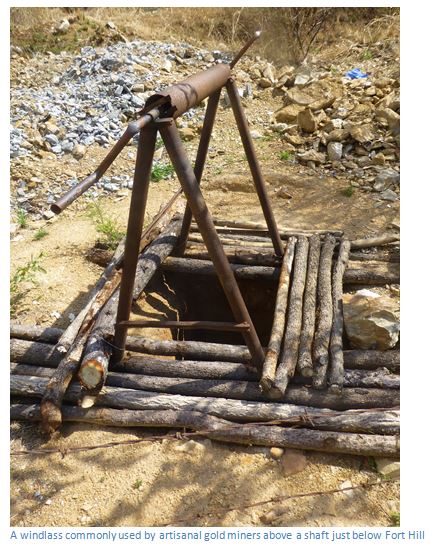

At Hartley Hill itself, the only structures still standing are the stone walls of Old Fort Hartley (1896-7) and the cemetery. The area is littered in contemporary gold workings in the form of shallow shafts and holes burrowed into the ground and mounds of earth and the occasional windlass for hauling up ore. Piles of quartz that have been picked out of the reefs awaiting transport to the three-stamp mill a kilometre away where it is pounded up to liberate the gold. In the same way the 1890 pioneers reported the ground covered with ancient workings, so things have not changed much!

The interesting features at Hartley Hill goldfield moving from west to east are:

(1) The Hunters Road blazed by Thomas Baines crosses the Chimbo Stream just west of Hartley Hills mining camp. A footpath today follows the course of the Hunter’s Road to the stream and the Chimbo Stream banks have been cut away on both sides with stones laid in the stream bed. A new track has been cut down the eastern bank, but the western bank appears to follow the original track.

(2) Hartley Hills mining camp was just east of the Chimbo Stream and 500 metres northwest of Old Fort Hartley, marked by two distinctive peaks; early photos show pole and dhaka huts, but all traces of them have gone. There is late Iron Age dry-stone walling on the top of the northern kopje, probably built as defence against amaNdebele raiding parties.

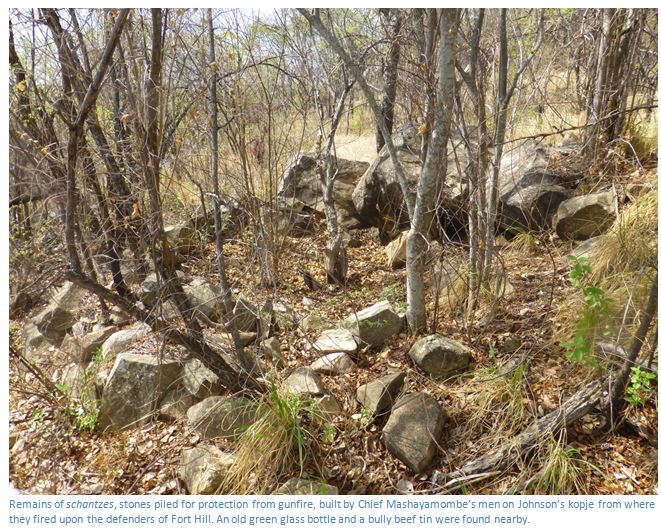

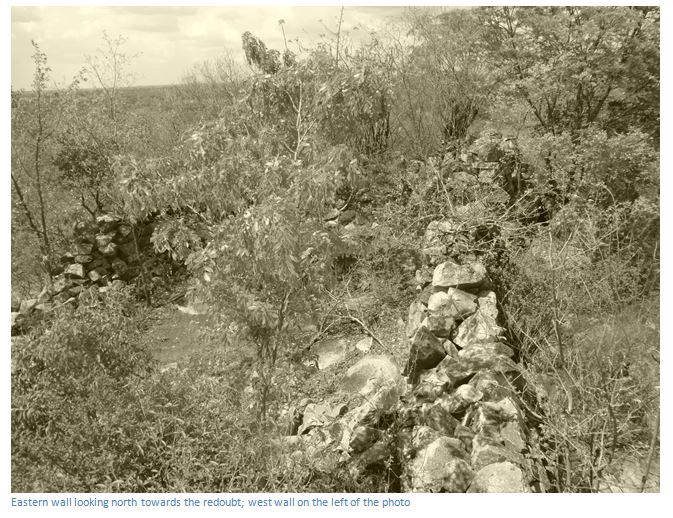

(3) Johnson, Heaney and Borrow’s camp (Johnson’s kopje) was on a small kopje just 200 metres north of Old Fort Hartley. The Old Fort Hartley defenders burnt down the camp huts facing Old Fort Hartley in April 1896 because they afforded cover to Chief Mashayamombe’s men. We found traces of brick and occupation debris at the base of the kopje. At the top of Johnson’s kopje, shallow schantzes have been dug out and lined with stones on the side facing Old Fort Hartley and it was from these that a sniping fire was made on Old Fort Hartley. Old Fort Hartley enjoyed a strategic advantage in that it is higher than Johnson’s kopje and the strongest dry-stone walling faces Johnson’s kopje.

(4) The house that Thomas Baines built has left no visible remains, although it was probably west of Johnson’s kopje and south of Hartley Hills mining camp.

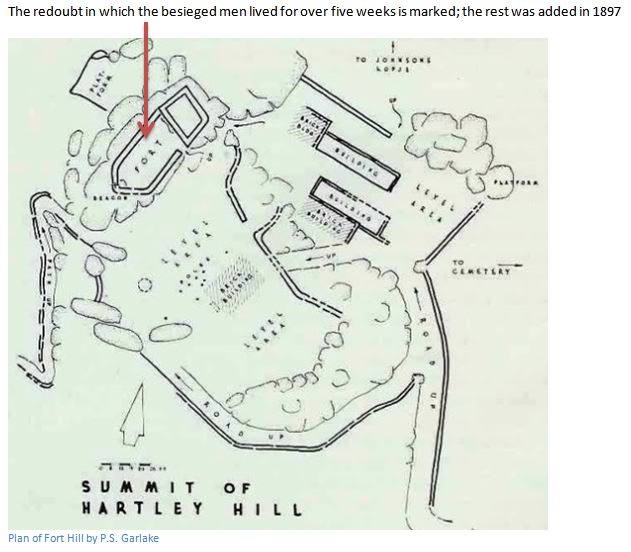

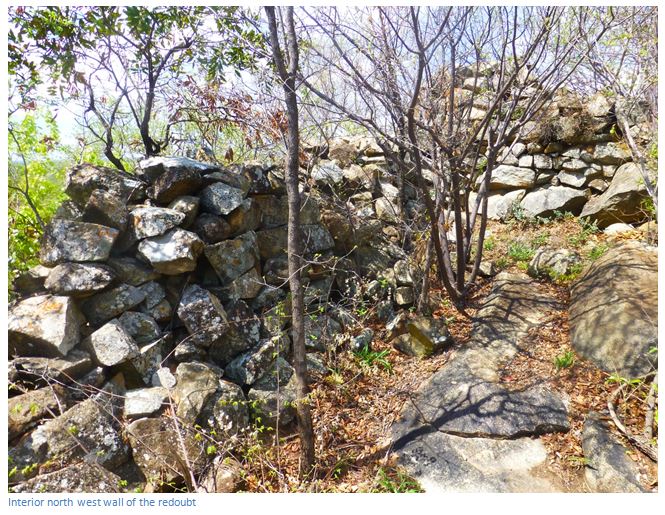

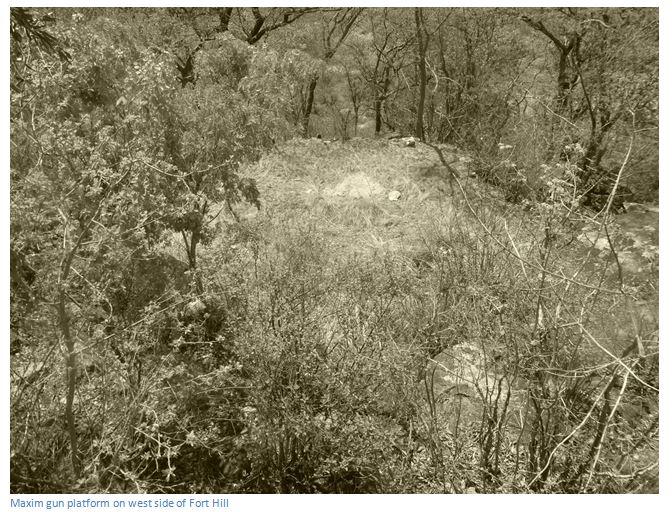

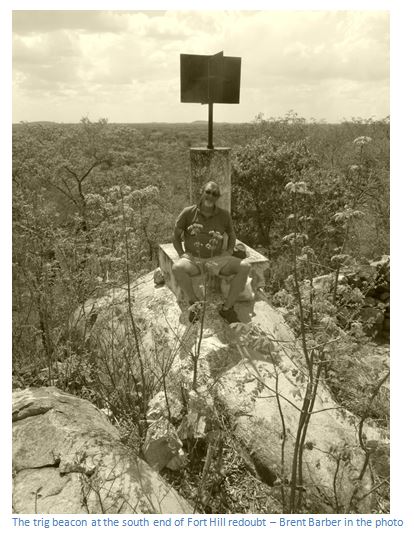

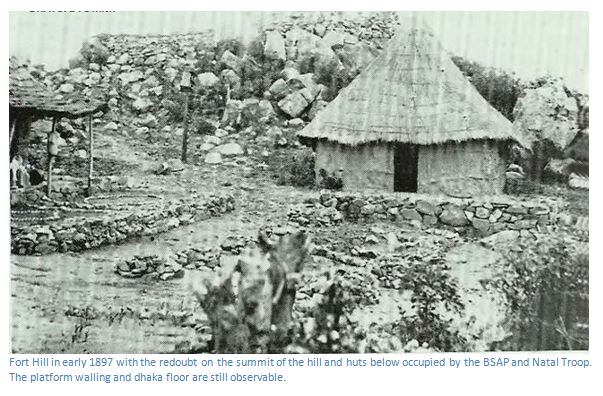

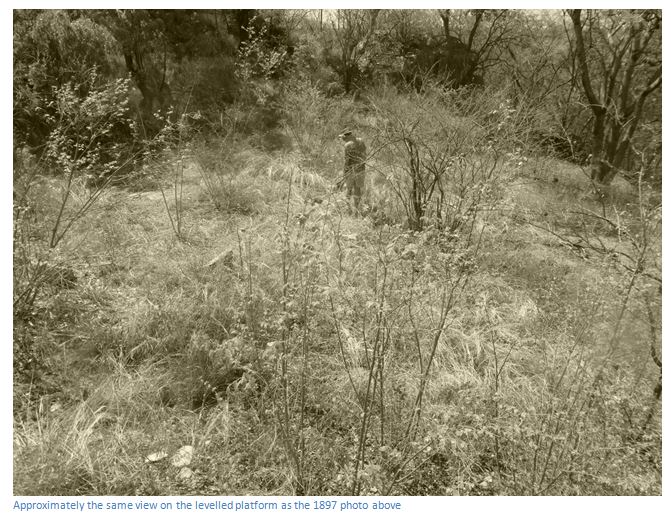

(5) Old Fort Hartley was built in 1896 and extended by the BSAP in 1897 and is still visible being built of loose granite rocks to a height of about 1.5 metres (5 feet) at the summit of the kopje below the survey beacon. The northern end has a redoubt with a rectangular structure measuring 4.5 x 3.5 metres and this may have been the original defensive position. The entrance is just below and the summit of the kopje has been walled. The access ways and levelled platforms where pole and dhaka and brick huts were built for the BSAP and Natal Troop between December 1896 and February 1897 are also visible as is the roadway built up the hill on the southern side, although it has been partly dug up by artisanal gold miners. Prior to the fort being built this was where Graham, the Mining Commissioner, had his camp.

(6) The long shelter marked on the Young Farmers Club (YFC) map is no longer visible as the area has been extensively dug over by local gold miners in recent years.

(7) In 2015 a large rondavel site still existed with its stone pillars extant but had been destroyed by the end of 2016 and many of the previous tracks are no longer usable.

(8) The Meikles Hotel cellar site was not observed and has probably been destroyed by gold digging.

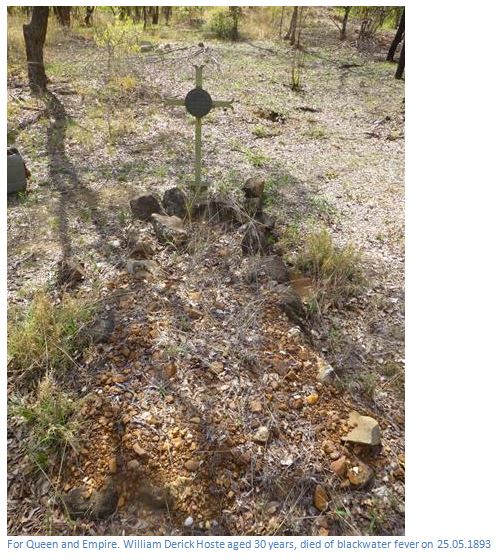

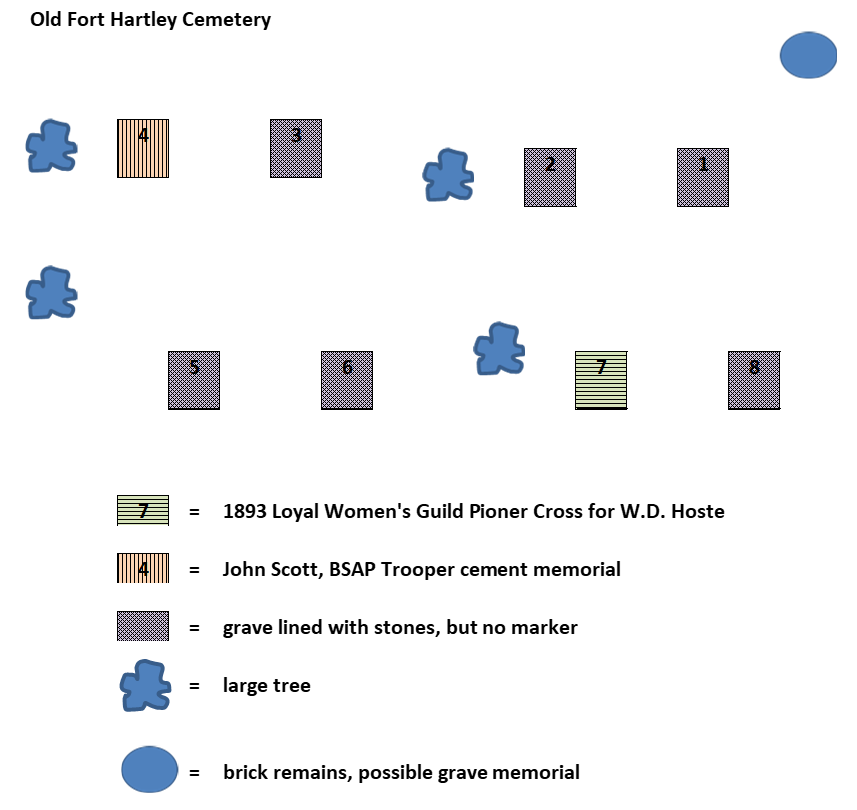

(9) The Cemetery site some 200 metres to the east still exists with eight gravesites. There is a Gregory grave marker for William D. Hoste and later grave marker for John Scott; the remainder are unmarked.

Hartley Hills played a prominent part in the First Chimurenga or Mashona Rebellion. The Umfuli River (now the Mupfure) formed a traditional boundary to Matabeleland and as news of the Matabele Uprising, or Umvukela grew, a meeting was held on the 4 April 1896 at the Mining Commissioner’s camp for the 34 Europeans in the vicinity, mainly prospectors and traders. The British South Africa (BSA) Company’s Medical Officer, Arthur Newnham, emphasized to the BSA Company that their location at Hartley Hill was important and reported that amaNdebele had come into the district, supposedly for work.

The BSA Company issued twelve Lee-Metford rifles and several thousand rounds of ammunition to supplement the privately held rifles. Twelve men, who were reluctant to abandon their claims and retire to Salisbury, began to fortify the hill. Percy Inskipp, the BSA Company Under Secretary wrote to check they had sufficient supplies saying: “we presume you are satisfied that in deciding to remain at Hartley, you are confident of being able to maintain your position.” Although news of the killings in Matabeleland was now common knowledge, Newnham replied: “we feel perfectly safe, are well off for food and unless peremptorily ordered, we mean to stick to our guns.”

On the 24 April a prospector, name not known, was attacked between the Umsweswe and Umniati (now the Munyati) Rivers and defended himself until his ammunition ran out, his servant reporting his death. On hearing the news that the AmaNdebele were now within sixty kilometres of Hartley Hills, the twelve defenders reinforced their defences at Old Fort Hartley and slept inside it at night.

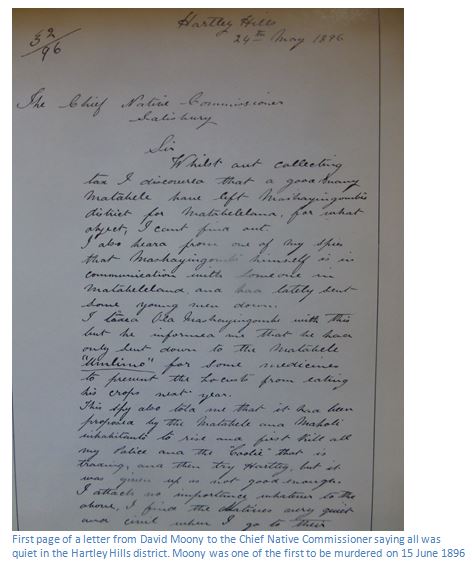

Below is part of a letter from David Mooney, one of the first victims, to the Chief Native Commissioner, W.S. Taberer, dated 24 May 1896; “Sir, Whilst out collecting tax I discovered that a good many Matabele have left Mashayingombi’s district for Matabeleland for what object, I can’t find out. I also heard from one of my spies that Mashayingombi himself is in communication with someone in Matabeleland and has lately sent some young men down. I taxed Mashayingombi with this, but he informed me that he had only sent down to the Matabele “Umlimo” for some medicines to prevent the locusts from eating his crops next year. This spy also told me that that it had been proposed by the Matabele and Maholi inhabitants to rise and first kill all my Police and the “coolie” that is trading, and then try Hartley, but it was given up as not good enough. I attach no importance whatsoever to the above, I find the natives very quiet and civil when I go to their…”

The men at Hartley Hill were still unaware that their real danger lay not with the amaNdebele, but just twenty kilometres away to the east in the seemingly peaceful kraal of Chief Mashayamombe. The Native Commissioner of Hartley, and author of the above letter, David Mooney, had established his camp close to the village of Muzhuzha Gobvu, a nephew of Chief Mashayamombe. Tensions had grown between Mooney’s men and those in Muzhuzha’s village. Three days before Mooney was killed, Mjuju, one of Muzhuzha’s men, beat the wife of Jim, one of Mooney’s men and when the women complained, Mooney thrashed Mjuju. Four men from Mjuju’s kraal ran out with guns which Mooney confiscated and sent to Thurgood, the Tax Collector at Hartley. Mooney then crossed the Mupfure River to the south bank and found the bodies of three Indian traders killed at their store, probably on 14 June 1896; whereupon a number of his men deserted.

On their return to Mooney’s camp next day they saw Chief Mashayamombe’s armed followers, led by his brother Chifamba coming towards them, and Mooney realised that his flogging of the Chief’s nephew and his men’s desertions were connected; he quickly mounted his horse and rode towards Hartley Hills with his remaining men. Just past the Nyamachene River, his horse was wounded and Mooney climbed a small kopje and was killed here in the ensuing gun battle.

His messenger January, real name probably Jarivau, managed to escape and from a cave watched two traders, Stunt and Shell walk into Muzhuzha’s kraal, where one was shot and the other ran off before being stabbed and their bodies were thrown into the Mupfure River. January then made his way to Old Fort Hartley and informed the men there of the tragedy. On hearing this news, all but two of their African servants deserted.

Chief Mashayamombe’s men now went on the offensive. The Chief’s nephew, Kakono, travelled over sixty kilometres west to the Umsweswe River to kill JC Hepworth; another group under the Chief’s brother, Chifamba Muchena, went east to the Beatrice Mine and killed Tate, Koefoed and four of their workers.

The list of European victims for the Hartley district in the first six days of the uprising is as follows:

| Victims killed in the first six days in Hartley Hills district | ||||

| Surname | Name | Title | Date | Where killed |

| Moony | David | Native Commissioner | 15 June 1896 | Mashingombi's kraal |

| Stunt | John | Prospector | 15 June 1896 | Mashingombi's kraal |

| Shell | A. | Prospector | 15 June 1896 | Mashingombi's kraal |

| Thurgood | Harry | Native Commissioner | 15 June 1896 | George's kraal |

| van Rooyen | Robert | Transport rider | 16 June 1896 | Hartley Hills road |

| Fourie | Benjamin | Transport rider | 16 June 1896 | Hartley Hills road |

| Tate | William | Mining Engineer | 16 June 1896 | Beatrice mine |

| Koefoed | S. | Prospector | 16 June 1896 | Beatrice mine |

| Wickstrὃm | N. | Prospector | 17 June 1896 | Umswezwe's kraal |

| Hepworth | John | Mine Manager | 17 June 1896 | Wallace's farm |

| Norton | Joseph | Farmer | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton |

| Norton | Caroline | Farmer's wife | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton |

| Norton | Dorothy | Farmer's daughter | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton |

| Fairweather | Nurse | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton | |

| Gravenor | Harry | Farm assistant | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton |

| Alexander | James | Farm assistant | 17 June 1896 | Porta Farm, Norton |

| Wallace | James | Prospector | 17 June 1896 | Hartley farm |

| Carrick | Edward | Mining Commissioner | 19 June 1896 | left Hartley Hill for Salisbury |

| Turner | A. | Storeman | 19 June 1896 | left Hartley Hill for Salisbury |

| Nelson | Thomas | Prospector | 20 June 1896 | Umswezwe's kraal |

With the news of the killings, the defenders moved permanently into Old Fort Hartley. They were Carrick, the Mining Commissioner, Newnham, the Medical Officer, Carlisle, the Store and Hotel keeper, and Messrs Ackland, Avery, Bradburne, Forbes, Hales, Loder, McRae, Turner and Warne.

The tiny garrison felt great anxiety for other Europeans prospecting or trading in the district, especially Harry Thurgood, and on the evening of the 18 June 1896 Carrick and Turner, with January the detective, left to warn him; but after finding Thurgood’s Farm ransacked they continued on to warn the inhabitants of Salisbury and were attacked on the way and killed near the Manyame River on 19 June, their bodies being found on the 21 July by Whites’ patrol with the letters they had been carrying.

A few hours after Carrick and his colleagues left on 18 June the Old Fort Hartley garrison was fired on from Johnson’s kopje about 200 metres away; so next day they burnt down the huts on Johnson’s kopje belonging to Johnson, Heany and Borrow which were affording cover to their besiegers. No direct assault was made upon the fort, as it was strongly built and fortified, but a daily and continuous harassing fire was opened up on them and they ran a gauntlet of fire getting water from the nearby Mupfure River. This action lasted between 18 June and 22 July with the firing most intense on the night of 2 July. The remaining ten defenders became very weary with continuous weeks of day and night guard duties.

Remains of schantzes, stones piled for protection from gunfire, built by Chief Mashayamombe’s men on Johnson’s kopje from where they fired upon the defenders of Old Fort Hartley. An old green glass bottle and a bully beef tin were found nearby.

On 5 July two African servants who had been sent from Salisbury with letters were pursued and killed within sight of Old Fort Hartley. However, the tiny force of ten, led by Dr Newham and Carlisle, who ran the local Store and Hotel, managed to hold out until they were relieved by a patrol under Capt. the Hon. C. J. White on 22 July.

When one visits Old Fort Hartley today, it does seem amazing that so few were able to hold out for so long and managed to fetch water from the Mupfure River under continuous sniping fire without any of them being wounded or killed.

Capt. C. White’s patrol with Capt. Biscoe, Surgeon Fleming, Capt. St. Hill, and Lieuts. Nesbitt, Eustace, Ogilvie with 210 Troopers and 40 friendlies left Salisbury on 19 July 1896 with the aim of relieving the small garrison of ten men at Hartley Hill.

White’s patrol had its first encounter with Nyaweda’s men about three miles on the Salisbury (now Harare) side of Norton's farm, where they had lined a kopje and fired upon the patrol. They were immediately attacked and in the ensuing fight Tpr. W. H. Gwillim of the Salisbury Field Force and a friendly were killed and four wounded. The patrol moved on, having some difficulty in crossing the Manyame River, and laagered for the night. Next day, they found the skeletons of Carrick, Turner and January and laagered at the Serui River before coming upon about 50 of Chief Chivero’s men between the Serui and Chimbo Rivers whom they routed with heavy loss. Rough stone walls had been built overlooking the road. There was also a bark rope stretched across the road with an empty bully beef tin with a stone inside to act as a warning bell and Chivero’s men were well stocked with food and ammunition.

That night the column laagered twenty kilometres from Hartley Hill and next day relieved the ten survivors; the late R. Carruthers-Smith, who was there on that day, told Col. Hickman how the patrol had galloped up the slope to the fort cheering and shouting and been greeted by the ten besieged men with joy and relief.

White's patrol remained at Old Fort Hartley for the rest of the day and began the return journey next morning, the 23 July, accompanied by the relieved garrison of ten men. They had intended to return by way of the Beatrice Mine, and crossed the Mupfure River with great difficulty, but instead of finding an open road as they had been led to believe, they faced broken country with kopjes overlooking the road, the perfect setting for an ambush. They re-crossed the Mupfure and returned not by the road past Norton's Farm on which they had come, but on the south road which joined the main pioneer road from Fort Victoria and crossed the Manyame River twelve miles from Salisbury. On the 26 July they surprised Gumboreshumba, the Kaguvi spirit medium at Mupfumera’s. Kaguvi escaped to Kaguvi Hill, south of the Mupfure River, but White claimed to have killed up to forty fighters and collected a great deal of tribute offerings to the spirit medium.

From then, the district was abandoned until 9 October 1896, when 522 European and 100 African troops under Lieut. Col. Alderson and Major Jenner, with three seven-pounders and four Maxim guns, attacked Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal. After three days they retired, having achieved little. Alderson realized the need for a fort, but felt the difficulties of transport and supplies, and the shortage of men prevented the establishment of one at this time, particularly as the rains were about to start.

Earl Grey, the Administrator, was extremely critical of Lieut. Col. Alderson saying: “Alderson and his mounted infantry made so rapid a promenade militaire through the country that in many places the result is nil and the natives are in a state of mutiny. Alderson committed two blunders, after his third attack on Mashayamombe he should have blown up the cave and left a fort behind. He did neither and the result is that Mashayamombe believes we are afraid and impotent.”

Following Earl Grey’s continued criticism; Old Fort Hartley was re-occupied on 1 December 1896 by the Natal Troop and two weeks later reinforced by Major Hopper and eighty men of the British South Africa Police (BSAP) with the fort being enlarged and pole and dhaka and brick huts being built. But the fort was in an extremely unhealthy position with endemic malaria that took a heavy toll on its garrison – there were seven BSAP deaths in the period January to early April 1897.

There are no personal accounts of the siege which is a pity. Old Fort Hartley is in good condition today, with the levelled off platforms built by the BSAP who subsequently moved in, well preserved with dhaka floors and walling and some occupational debris such as broken bricks and the occasional horseshoe. The area surrounding the Fort has been completely turned over by gold miners, probably not unlike the state it was in when Hartley and Baines were here in 1870! Even the access road up the kopje is cratered with gold diggings.

Old Fort Hartley Cemetery

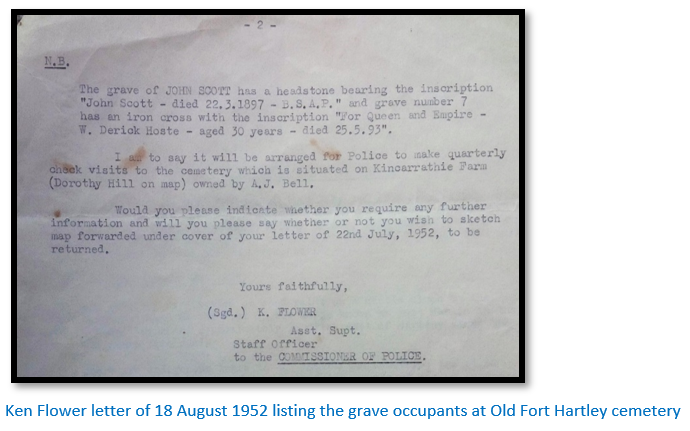

A BSAP grave list page is listed in the Loyal Women’s Guild graves register [NAZ 1/4/1] but is extremely incomplete for Old Fort Hartley. The ’96 Rebellions BSA Company Reports list who was killed and died from other causes at Old Fort Hartley but is not clear about where they are buried…some may have been buried in the Pioneer Cemetery at Salisbury, now Harare. The best source for those buried in the cemetery is from a letter written by Ken Flower (died 2 Sept 1987) who became the first head of the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) and was in post 1964 – 1981; the letter kindly sent to me by Iain Dunn.

A copy of the letter is at the end of this article.

| Burials at Old Fort Hartley Cemetery | ||||||

| Grave | Surname | Name | Title | Date | Reason | |

| 1 | Livingstone | William Kinloch | Trooper, BSAP | 1 January 1897 | Fever | Note 1 |

| 2 | Overstall | Frederick | Trooper, BSAP | 11 February 1897 | Fever | |

| 3 | Butcher | Harry | Trooper, Natal Troop | 16 February 1897 | Fever | |

| 3 | Tenant | Robert | Hospital-Sergeant, BSAP | 26 February 1897 | Fell off a rock and killed | Note 2 |

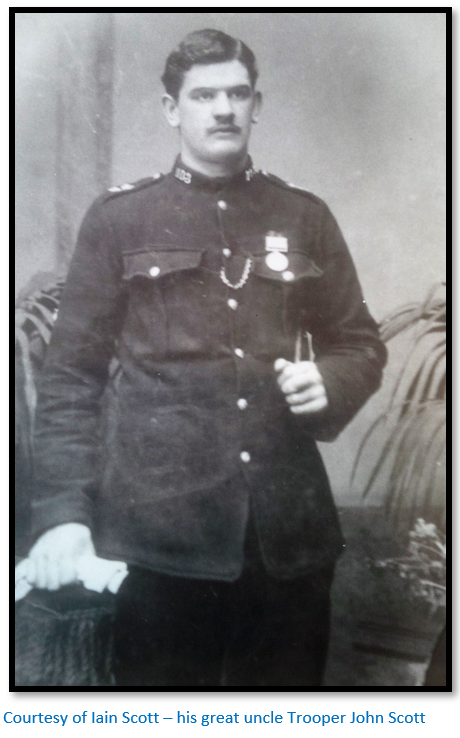

| 4 | Scott | John | Trooper, BSAP | 22 March 1897 | Fever | |

| 5 | Foster | John Lowry | Trooper, BSAP | 23 March 1897 | Fever | |

| 6 | Sims | George | Trooper, BSAP | 2 April 1897 | Fever | |

| 7 | Hoste | William Derick | Prospector | 25 May 1893 | Fever | |

| 8 | Jay | Edgar | Corporal, BSAP | 27 Dec 1897 | Fever, died at Makori | Note 3 |

| Some details are from The '96 Rebellions BSA Company Reports | ||||||

| Note 1: The '96 Rebellions state 12 January 1897 | ||||||

| Note 2: The '96 Rebellions state 26 July 1897; but if there are two burials in the grave, the February date makes more sense | ||||||

| Note 3: Ken Flower letter states date of death and reason unknown, but The '96 Rebellions have details | ||||||

The grave numbers correspond with the cemetery diagram included later in the article.

Derrick Hoste is the only grave with a Loyal Women’s Guild Memorial Cross [see the article The Loyal Women’s Guild and the Pioneer Memorial Crosses under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Two others deaths are listed in The ’96 Rebellions BSA Company Reports as having died at Hartley, but there is no trace of their graves:

| Surname | Name | Title | Date | Reason |

| Varndell | C.R. | Sergeant, Natal troop | 6 April 1897 | Fever, died at Hartley |

| Lee | Herman | Trooper, BSAP | 30 June 1897 | Fever, died at Hartley |

W.D. Hoste was the younger brother of Henry Francis “Skipper” Hoste, who resigned as Captain of the RMS Trojan to join the Pioneer Column as Captain of B Troop. The remaining victims are from when the fort was re-occupied by the BSAP from December 1896 to March 1897. [See the separate article on extracts of Derick's life from the book "Gold Fever" written by "Skipper" Hoste on the website: www.zimfieldguide.com]

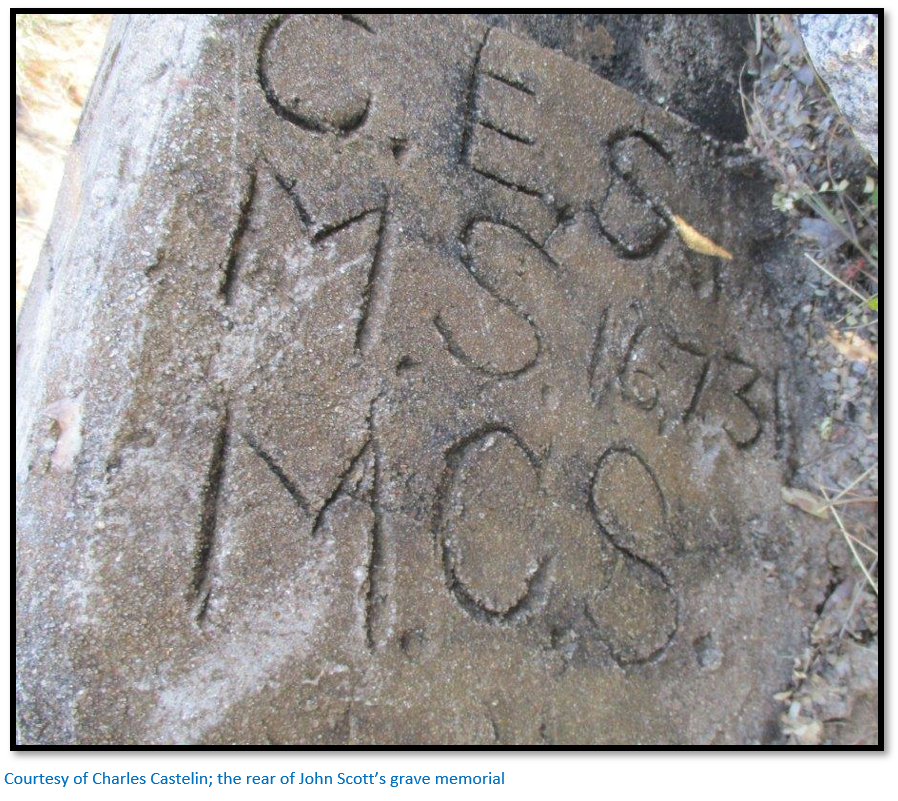

I am grateful to Charles Castelin for pointing out that the reverse of the concrete memorial to John Scott bears the following initials of family members (G.E.S / M.S / M.C.S) and the date 16 July 1931.

Iain Dunn writes that John Scott was his great uncle; the initials above are CES = Charlie Scott, John’s brother who cast the grave memorial; MS = Madge Scott, Charlie’s wife and MCS = Marjory Scott their daughter. Iain says Bill and Charlie, John Scott’s brothers, located his burial place in the 1920’s and identified it from the original wooden cross which had been eaten by white ants but was still legible on his grave. Charlie cast the grave memorial on his farm at Ugie in the Eastern Cape and erected it on the grave.

Iain Dunn provides some personal details on his great uncle; “He had been a volunteer ambulanceman in Stirling, so very likely was serving in a medic capacity himself at the camp, when he got the fever. From talks my Grandfather and his brother Charlie had with former troopers who had been serving with John, he had become delirious with the fever, and had stumbled down the hill, dying very close to where he is buried. He had apparently been very popular with his comrades as he was very good with a harmonica - a significant asset in the middle of the bush in the days before radio and streamed music!”

The BSAP compiled lists of the names of those buried at each site around the country before 1908 that included decaying or lost grave markers. Listings were then drawn up by the Loyal Women’s Guild (LWG) and sent to the Gregory iron foundry in Cape Town to be cast as the familiar circular cast iron grave markers. Those who died prior to the death of Queen Victoria on 22nd January 1901 are headed “FOR QUEEN & EMPIRE” and those after are “FOR KING & EMPIRE.” The BSAP then placed the markers, but not always on the correct graves; so the current positioning of the grave markers should always be treated with caution, although that of Derrick Hoste does coincide with Ken Flower’s letter.

The grave markers of W.D. Hoste and J. Scott are the only ones still in existence at Old Fort Hartley. The LWG aim was to replace decaying or lost grave markers with memorial crosses so that the location of the grave occupants would not become lost. The original wooden crosses were likely to be eaten by white ants or burnt in grass-fires.

The LWG graves register [NAZ 1/4/1] has an entry for Old Fort Hartley cemetery with only John Scott listed on the grave diagram and that in grave 8. There is a note stating John Williams and Walter Henry Parsons are buried here with burial dates for 1899 and are said to each have an iron cross with an inscription, but all the other graves are said to be unmarked. A note on the same page states a Mr Begbie claimed that Cecil Butt and Derrick Hoste were buried at this site but was not sure in which graves. The LWG graves register shows that only a Pioneer Memorial Cross for W.D. Hoste was ordered.

At the end of March 1897 Old Fort Hartley was abandoned and Fort Martin constructed 18 kms to the east and one and a half kilometres from Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal on the north bank of the Mupfure River. Kaguvi, the spirit medium, was based on the south bank nearby at Chena’s kraal. [For further details see the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Hartley (the 1:250,000 map calls it “Village Main” after the Johannesburg mining company) moved from this site near the confluence of the Mupfure River and the Chimbo Stream in 1899 in anticipation of the arrival of the railway which arrived in 1901. In 1982, the town of Hartley was renamed Chegutu.

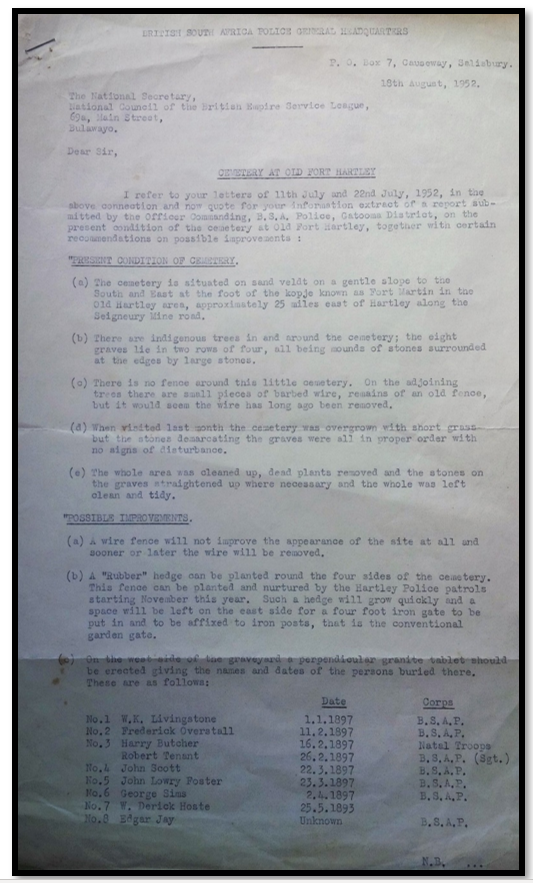

Ken Flower letter of 18 August 1952 – the best source of information on the Old Fort Hartley Cemetery

Iain Dunn’s grandfather Bill Scott and brother of John Scott wrote to the National Council of the British Empire Service in 1952 complaining about the neglected condition of the cemetery. The BSA Police had a responsibility to visit all of the old cemeteries every three months and report on any problems. This was a task they undertook prior to the Loyal Women’s Guild taking on their 1908-10 project of replacing decaying or lost grave markers with Pioneer memorial crosses. The National Archives has many BSAP reports in the LWG files on all the old cemeteries including at Filabusi, Ngwenya, Sinoia and Que Que.

In fact the BSA Police had their own Pioneer and Police Graves Register pre-1923 [NAZ S152] that appears to have been written up by Lieutenant-Colonel and BSAP Commissioner (1903 – 1909) William “Billy” Bodle.

Clearly the bulk of Ken Flower’s letter has been taken from one of the BSAP quarterly reports submitted by the OC at Gatooma. I am very grateful to Iain Dunn for making this letter available; it clears up the mystery of who was buried at Old Fort Hartley cemetery.

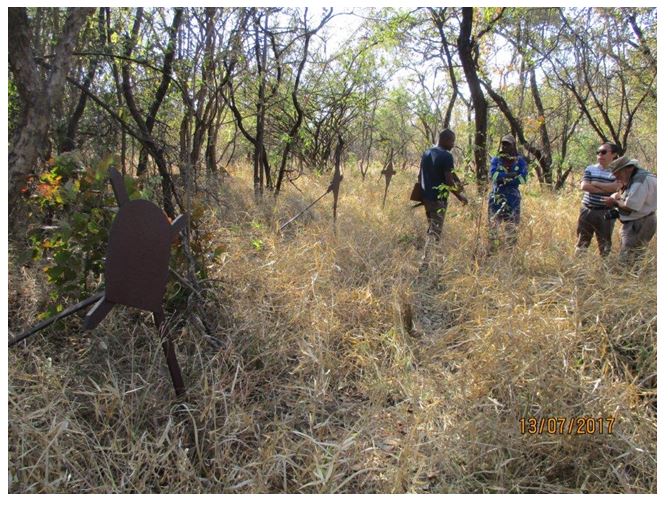

The other Hartley Hills cemetery near the Jefta Reef

Charles Castelin found another cemetery with three simple metal replicas of the GLW iron crosses near the Jefta Reef on the banks of the Mupfure River. The replicas are made from metal plate without details of the deceased names, or date of death and were probably made in a local mine workshop and are shown in the photograph below:

From the graves register NAZ S152 I found the following names listed as being buried at Old Hartley cemetery:

| Surname | Name | Details | Date | Place |

| Eldrid W.T. | ex BSAP | 23/05/1916 | Old Hartley cem | |

| Howell G. | 03/09/1909 | Old Hartley cem | ||

| Palmer G.G. | 06/06/1909 | Old Hartley cem | ||

| Turner | Pioneer | Old Hartley cem |

Hartley moved to the present site at Chegutu just before the railway arrived in 1901. The last burial at Old Fort Hartley cemetery was that of Peter Jay at 27 December 1897 and presumably deaths after 1901 were buried at Hartley. Those above may have requested to be buried near the Jefta Reef or the Mupfure river and not at the new Hartley town cemetery.

The map below, also from Charles Castelin, shows the location of this lost cemetery.

For further related articles including: Early European visitors to Hartley Hills goldfield / Thomas Baines and the Hartley Hills goldfield / The search for Willie Hartley’s grave / Chief Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and the Cemetery see the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

Acknowledgements

T. Baines. The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa. Books of Rhodesia 1968

Col. A.S. Hickman. Norton District in the Mashona rebellion. Rhodesiana No. 3. 1958

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 -1897. Rhodesiana No. 12. Sept 1965.

W.H. Brown. On the South African Frontier. Books of Rhodesia 1970

Col. A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. BSAP Co. 1960

The ’96 Rebellions Report by the BSA Co. Books of Rhodesia 1975

Ken Calder who accompanied me on my first visit and Brent Barber who came on the second visit.

Charles Castelin for photographs and map

Iain Dunn for photographs and information