William Irwin, a casualty of the assault on Kunzwi's kraal, Mashonaland

In the churchyard of St. Mary Magdalene’s Church, Hayton, east of Carlisle, Cumberland, is the following inscription on a gravestone[1] for the Irwin family:

Photo courtesy of Berenice Baynham

Also William George, youngest son

of the above George and Bridget Irwin, who was killed in the attack on

Kunzi’s kraal, Mashonaland, South Africa.

Born Nov. 3rd, 1868

Died June 20th, 1897

This article explores the circumstances behind the death of this young man, just 28 years old.

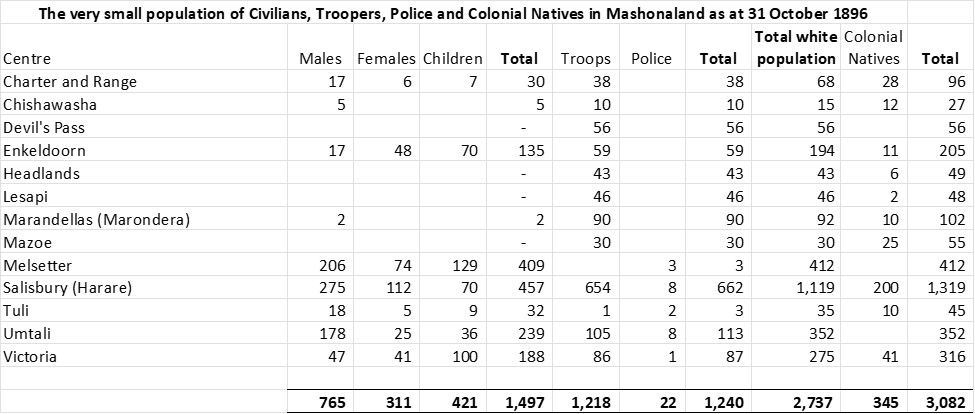

Mashonaland in 1896 – the perfect storm

Few settlers in Mashonaland at New Year in 1895 realised how eventful the next two years would be. Judge Vintcent was acting administrator for Dr Jameson, who was absent at the time, his whereabouts uncertain, although some thought he might be in Bechuanaland arranging for a strip of land to be transferred to the British South Africa Company for the use of the planned railway.

On the 3 January 1896 the judge was with Hugh Marshall Hole[2] having dinner when a batch of telegrams arrived – the telegram service had been down a few days, a common occurrence in the rainy season. The guests waited with mild interest to hear the list of New Year’s honours, but were shattered to hear: ‘Capetown 31 December, Great excitement caused here by news that Dr Jameson has crossed Transvaal border with 800 mounted men with Maxim and field guns. High Commissioner and Chartered Company repudiate his action and former has sent two telegrams demanding his instant return…’ The dinner party broke up, most left to seek further news at the Club, or the newspaper office.

On the little information available, the populations at Bulawayo and Salisbury were unanimous in condemning the Reform Committee at Johannesburg for allowing Jameson, Willoughby and White with almost the entire country’s police force to become President Kruger’s prisoners but could only grind their teeth in impotent rage.[3] The excitement died down when it became known that the principal officers would not be shot but sent to England to stand trial.[4] Little did they know what the year 1896 would bring.

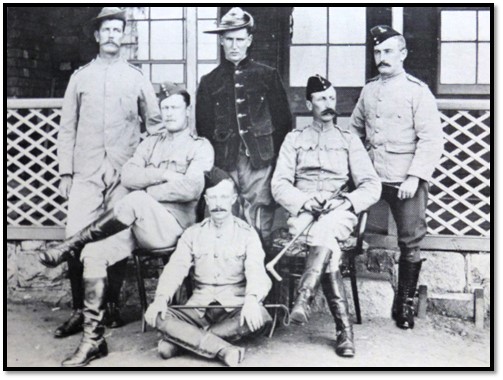

National Portrait Gallery, Dr Jameson and officers of the Jameson Raid on their way to England to stand trial[5]

Standing (L-R) Capt C.L.D. Munroe, Capt Kenneth J. Kincaid-Smith, Major the Hon Henry F. White, Dr Leander S. Jameson, Lt-Col Charles H. Villiers, Major the Hon Robert White, Lt-Col John B. Stracey-Clitheroe, Col. Harold M Grenfell

Sitting (L-R) Sir John C. Willoughby Bart, Capt Charles F. Lindsell, Lt-Col Sir Raleigh Grey

The Jameson Raid depleted Matabeleland and Mashonaland of their police forces, leaving a very small population of settlers scattered in various small settlements and isolated farms and mining camps and that along with the other factors, probably was a major contribution to the outbreak of the Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela.

Rinderpest disease crosses the Zambesi river

February 1896 brought the Rinderpest.[7] This was a disaster for a country that relied on trek oxen hauling wagons for its supplies. Transport riders were forced to leave their heavily laden wagons in the veldt as all their oxen died. The railway to the south ended at Mafeking, 800 miles (1 287 kms) from Salisbury and the narrow gauge from Beira had its terminus at Fontesvilla on the Pungwe river and would only be connected with Umtali in February 1898.[8] Within a short period the existing routes were lined with rotting carcases and the oxen had died like flies. In vain the authorities tried to stop the rinderpest’s spread south by killing whole herds of cattle, including those of the amaNdebele, Mashona and settlers.[9]

Matabeleland experiences the political fallout

Local people had in the previous decade endured drought and locust plagues, the rinderpest caused considerable economic and social distress in African society and now many believed through suspicion and rumour that the rinderpest had been spread deliberately by the settlers to take away their wealth. The widespread slaughter of cattle herds in an attempt to contain the disease created further tension.[10] Other grievance included the imposition of the hut tax and large-scale land appropriation for settler farms.[11] Local leaders emerged who were willing to use these grievances and turn them into a general resistance movement.

Then came the news that Jameson and almost the entire British South Africa Company Police force[12] had surrendered to the Boers at Doornkop, leaving only the hated Native Police and the Native Commissioners to enforce the rule of law. Towards the end of March 1896, the amaNdebele rose up in a coordinated rebellion (the Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela) and before the settlers had realised the full danger, over 150 of them, mostly living in isolated farms, mines and trading stores had been ruthlessly butchered, in some cases with their wives and children.

The initial Mashonaland situation

News of the uprising reached Salisbury on 25 March 1896 and the first reaction was to send a force to the aid of Bulawayo and Gwelo (Gweru). Within a few weeks a force of 150 Rhodesia Horse Volunteers under Major Robert Beal had been mustered, taking half of the rifles and Maxims kept by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) and almost all the serviceable horse. There was much grumbling from the remaining Rhodesia Horse Volunteers who were kept at Salisbury to protect the women and children.

The Mashona were considered peaceful and trouble was not expected. This situation continued for two months with traders, prospectors and farmers remaining in their isolated places and going about their business.

The BSAC did issue some preliminary warnings

On 27 March 1896 when news of the rising in Matabeleland broke, Percy Inskipp, then Jameson’s secretary, wrote to the Mining Commissioners and Native Commissioners of each district warning them to keep a sharp lookout amongst the local natives in their district, reporting at once if they noted any signs of disaffection. In the event of suspicious activities they were to direct the settler inhabitants to proceed to Salisbury at once.

This was followed up on 14 April In the Government Gazette when Judge Vintcent issued a warning ‘Note to Prospectors and Others’ in which he said he had: “no reason to believe that there is any probability of a similar rising of natives in Mashonaland” and continued with the advice that there should be vigilance in case advantage was taken of the crisis to attack and loot isolated stores, mining camps and farms. Those who lived in such places were told that because the area was very extensive there might be difficulties of “speedily affording relief” if certain emergencies arose. Therefore, they were asked to report any suspicious circumstances to the nearest BSAC official, and all possible steps should be taken by them personally “to place themselves in a position of defence and security.” However, it is extremely unlikely that the persons to whom this note was issued ever read or had their notice drawn to this Government Gazette.

The Lomagundi Native Commissioner, G. H. Mynhardt, seems to have thought that local natives were unlikely to cause trouble and told the Chief Native Commissioner, "I don't think it necessary to keep a watch in this district for Matabeles as I don't think they will ever pass through here." Nevertheless, he did ask for some sort of protection, just in case, saying, "It is highly necessary to have some rifles and ammunition here. I haven't a single round of ammunition in camp."[13]

The Lomagundi Mining Commissioner, A.J. Jameson reported that most miners left the district and that, "the effect of the outbreak in Matabeleland has been to put a stop to mining and prospecting to a great extent. Besides those employed at the Ayrshire mine there are not a dozen men prospecting or doing development work."[14]

Some districts responded to the Gazette Notice. A petition, signed by fourteen Mazoe residents, was sent to the BSAC requesting ammunition. All had rifles, but limited ammunition, and one thousand rounds was sent with instructions that they were for “judicious use” only. An anonymous article in the Rhodesia Herald mentioned theft and looting in the Mazoe district, and since the Police had withdrawn, their camp had been vandalised and other camps had been robbed.

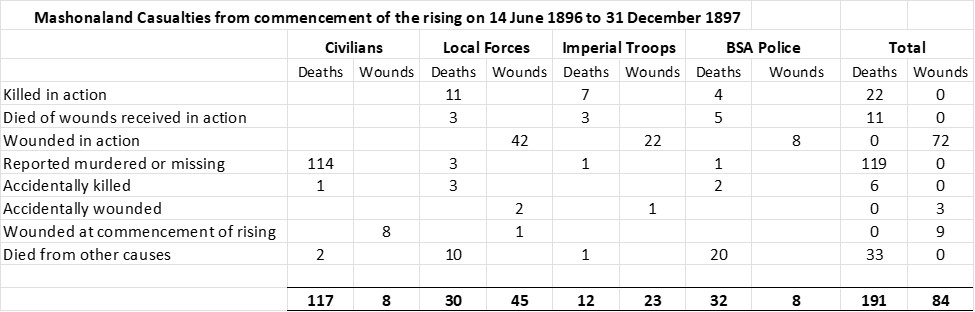

Reports of the first casualties in the Mashonaland Rebellion or First Chimurenga

The first casualty was a prospector named J. Docherty who, Jameson reported, had been "murdered by his boys at the Alaska Mine" with his body thrown down the sixty-foot shaft by his killers.

On 14 June a group of Chief Mashayamombe’s[15] supporters, including some amaNdebele, killed Tate and Kofoed, the mining engineers, and four Zambesi natives at the Beatrice mine.

A Zambesi native at the Ayrshire Mine warned the dozen or so miners there of what was happening. They formed a laager and on 22 June the whole party left for Salisbury. The Ayrshire mine party ran into an ambush of between 70 - 80 rebels and had to hide in a river until dark. When their food ran out, they lived on wild beans and roots, until on the 27 June they met a patrol from Salisbury, under Captain Taylor of the Natal Troop of Volunteers and Lieut Eustace of the Salisbury Field Force, who escorted them to safety.

Not everyone was so lucky. Herbert Eyre, an Umvukwes farmer in the Lomagundi district, was killed on the doorstep of his house on Sunday, 21 June: Trooper Arthur Young, of the Police; Mynhardt, the Native Commissioner and A. J. Jameson the Mining Commissioner, both quoted above, and James McGowan, a prospector, were all killed at their camps.[16]

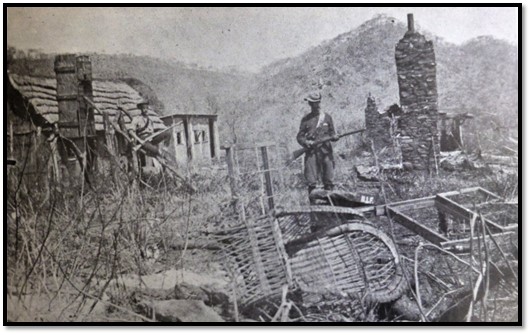

The Norton family on their farm 15 miles west of Salisbury were all killed. Colin Harding accompanied a patrol of mounted infantry under Capton Pilson on the 17 September. He writes, “the scene at Norton’s farm which met my eyes as I arrived there, I shall never forget.” They exhumed the bodies which had been hurriedly buried when discovered on 17 June and gave them a proper burial.[17]

NAZ: The Norton farm outside Salisbury after all the household had been killed

Within a week, killings had taken place throughout the districts and 114 civilians were dead.

With communication to many isolated places slow, many settlers remained in ignorance of the danger and all the remaining horses were gathered and patrols sent out to the farms and mining camps to rescue them including to Mazoe and Abercorn. Some groups elected to stay and fight,[18] others were forced into siege situations.[19] On 18 June the telegram to Salisbury from those besieged at the Alice mine at Mazoe advising of their plight was accompanied by reports of new killings coming in almost by the hour and revealed the rising was widespread throughout Mashonaland. In response volunteer patrols such as the one to Mazoe led by Lieut. Dan Judson with half-a-dozen volunteers were hurriedly got together and despatched the same evening.[20]

NAZ: Salisbury defence force volunteers, Dan Judson sitting fourth from left

Salisbury fortifies the gaol

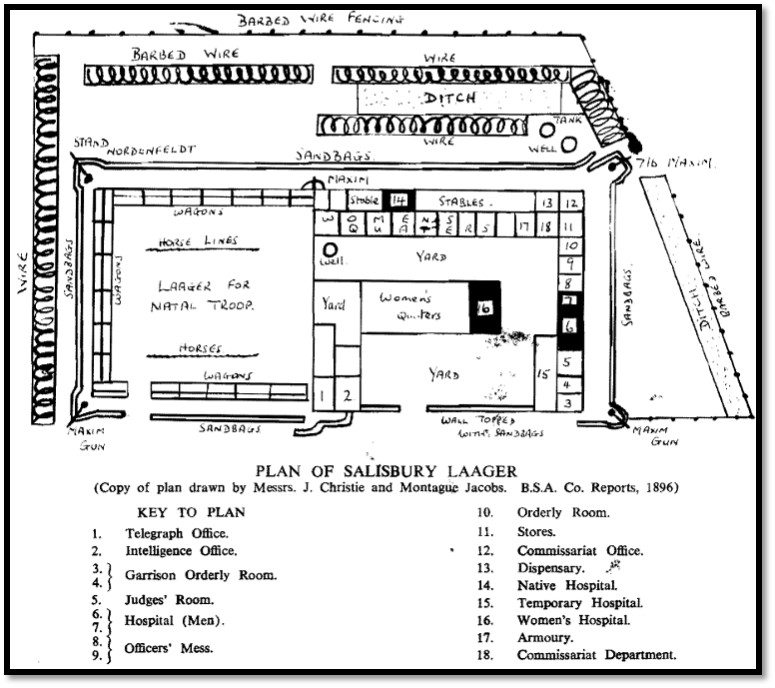

The only substantial brick building in Salisbury was the newly-built brick gaol, now hastily converted into a fort.[21] By the evening of 20 June, Salisbury’s citizens were safe inside the defences. There were 700 in all, including 126 women and 127 children, who were huddled into cells 12 ft. x 10 ft. with the scanty bedding they could collect in the hurried flight from their homes.[22] The large ward was used as a dormitory at night and messroom by day. An outer wall of sandbags was put up with barbed wire entanglements, four Maxims and a Nordenfeldt gun at the corners. The ox-wagons that had brought many occupants into Salisbury were used as another barrier and Salisbury settled into a siege routine.

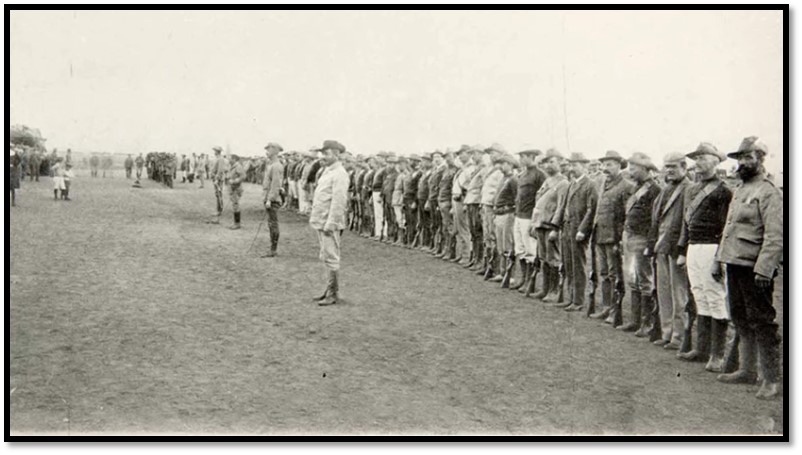

On 19 June Judge Vintcent declared martial law and all public houses were ordered to close by 6pm. The defence of the town was entrusted to the remaining 60 men of the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers and the remaining 250 men fit for active service. Most of the Chartered Company’s rifles had been issued to Beal’s force now at Bulawayo, but there were others in private hands, and these were commandeered and issued to those fit for duty.

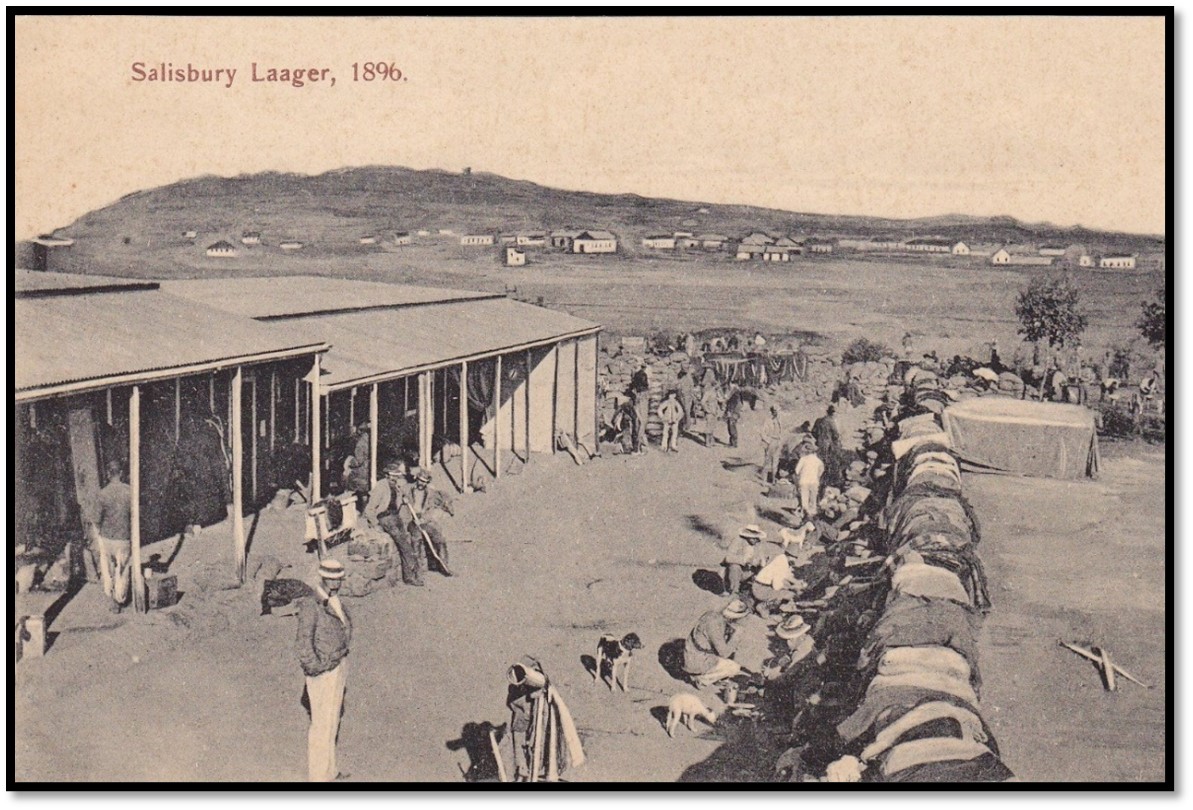

NAZ: Salisbury laager 1896, view from the gaol across the Causeway to the Kopje, officer’s mess, orderly room and stores on the left

This letter written from Mashonaland by Ephraim Nicholson of Morpeth, Northumberland and printed in The Morpeth Herald, Saturday, 17.10.1896 provides a good summary of events

Salisbury. Mashona Land, 9 August 1896. The last letter I had from you was dated 23rd of April. We've had no mail for 11 weeks and the wire has been down a great part of that time, so we have been shut out from the world. I will tell you of the times we have had. I had a note of dates but have lost most of them. I was staying at the farm… miles out of Salisbury and on Tuesday morning, a Mr Bray rode up to say that Tait [Tate] and Krupper [Koefoed] had been killed at the Beatrice, 30 miles out and that we had better come into town. I stayed all day, ready with rifle and revolver, and came in at night. Then a public meeting was called and volunteers who had rifles were asked to come forward for picket duty that night, and 25 fell in, including myself. We had to parade at 7:30 with blankets and topcoats. We were marched round the town. The section I was in (six of us) was taken 600 yards past the judge’s house. We had two hours on and four off, keeping in touch with the next man stationed 500 yards off. It was a very dull night, and we were in long grass, and the natives had been seen five miles out. This was my first attempt at soldiering. I did not feel over comfortable, but I had the old dog “Jim” with me and I depended on him a good deal. (I must break the story to tell you, poor Jim to my great grief, died on one of the patrols)

Next day martial law was proclaimed. Everyone was ordered into laager which was the prison. Then I turned soldier in earnest, fell in, and had the drill fairly well off, and was a full trooper. We had the walls to man at night and do picket duty; The pay was 10s a day and the scoff not bad. I was in C Troop, under Captain St Hill, a good fellow. I volunteered for Abercorn but got the usual answer that I was too big for any of the horses, and no foot sloggers were wanted. The anxiety and duty were relieved with fun and by-play. Our mess of ten, thinking the officers put on rather too much side, constituted ourselves into the reform committee. One order issued by the officers was that no trooper would be allowed to speak to an officer unless he was accompanied by a non-com. We replied to that by posting a notice that no officer would be allowed to speak to a trooper unless he was introduced by a native. Having got coloured puggarees for our hats and striped calico for our sleeves, we visited all the messes, asking the men if they had any complaints to make, if they had sufficient food and ‘dop’ [liquor] and if any of them would like to be promoted. In time, two sergeants came giving us the option of taking off the stripes or being taken to the guardroom. We took them off, of course. An order came out that we had to man the walls at 5:30 every morning as the natives were expected to attack at sunrise. Even then, plenty of joking went on, much of it at the expense of the officers, who had their photos taken and publicly exhibited, though they had done actually nothing but issue orders and countermand them.

One morning I intimated that I was going to give away 400 Victoria Crosses, for which all were eligible except those who had been offered promotion. The fear and incompetency displayed was most annoying. Think of the seven men at Abercorn and the ten at Hartley, and for 28 days nothing done for their relief. When Duncan arrived with one man from Charter, I told some of the officers they should take their photos down, and instead of making fools of themselves any longer, put up Duncan's portrait in place of their own.

Duncan lost no time. With 60 men who volunteered he went to Abercorn and brought in the men, except for Jack Rowland, who died on the road. Of the seven, four were wounded. They had been surrounded by natives for 24 days, and for some days they had not had a drop of water. On Duncan's return, I got an address of thanks to him drawn up. The Revs Shannon and Els put it into proper expression. It will cost £50 and was signed by one hundred the first day. Had Duncan been two days later every one of the Abercorn men would have been dead. About 140 have been killed outside and I knew nearly every one of them. Some men just happened to come in on business and were saved. Others just went out and were killed. Ashton just came in in time; two days later, he would have been among the killed. (Ashton is the eldest son of Mr. T Ashton, woollen manufacturer Abbey Mills, Morpeth) After we had got fairly into drill, we had only to fall in at 7 o’clock and 5 o’clock.

So on 4 July I walked out to the farm taking rifle, bandolier and revolver with me. I stayed all day and put up a small pump. We had one Cape boy and two natives. On Monday, the 6th, Ashton and I drove out. Tully went out on the 7th. That night the natives came, killed the Cape boy, and stole the donkeys and cattle, but the natives got in here. I never thought the natives would have come so close to town. I was out with two small patrols to bring in grain and burn kraals.

On Sunday 19 July, 60 men on foot were wanted for Hartley Hills. Ten men were known to be there. I volunteered. The column was made up of 140 mounted men, 60 foot, 40 Zulus, two Maxims and one seven-pounder. When I turned out, people said, “you will never walk, you should not go.” But I replied, “I'll come back alright.” I fell in, just in my shirt and trousers, no coat, no collar. I put the top coat with my blankets on top of one of the wagons, I walked all the way, not another of the 60 did it. I was in splendid order, my feet never flinching. Young fellows did not go three miles out of town till they had to ask for a ride. We had 10 mule wagons with our provisions, mealies and kit. One morning I did 15 miles before breakfast, just a drink of coffee at 5:30. We had only two meals a day. When we got back there I was the hero of the foot men. St Hill, the captain said to me, “old man, there’s not another like you, you shame the young ones.” I never felt better and was able to do 23 miles the last day in. I had often wondered what it would be like to be under fire. Well, it is nothing.

On Monday 20 July, nine miles out, we started at 6 am and marched on. At 8:30 we heard the first shot from behind a stone kopje, which was charged by A troop. We had one white killed[23] and Kerr and Arnot shot through the breast, two Zulus killed and two wounded. Then we trekked on. About two in the afternoon we heard heavy firing and C troop was drawn up. We were marched forward six paces apart, to storm the kopje on our left. I was on the left flank and a rare volley we got as we charged them. We turned along the top and got in behind stones. I got behind a large tree, looked over and saw a big native just turning round to fire when I dropped him. Then a bullet whistled past me on the left, so I crept up behind the stones and heard the man on my right shout, “fire at the gun.” I looked over and saw a tree about six yards off in a slanting direction to my left. I could see a native’s back sticking out five or six inches. He was sitting and had a hole through the tree and through the hole he was pointing his gun. I missed him the first shot but got him the second. I secured his gun, which had been taken from one of the farms. We killed about eleven and the rest we chased across a vlei, where the horsemen shot them down. The firing was fearful, we could not see who it was, but for about ten minutes it was very alarming. St Hill said I was like a two year old on the kopje, although to tell the truth, I was a bit out of breath. We were fired at all along the road, but as the men at Hartley had to be relieved, there was nothing for us but just to march on. We got to Hartley and our old friends were glad to see us.

Next day we started to come back by another road. We got out of the track and were close on to Mashayamombe’s, one of the very worst strongholds. We had to turn back and so lost three days. We got here on the 29th and got a great reception. On the 26th, while on the return march the horsemen of the column had a skirmish. They brought in 300 cattle, 10 donkeys and 100 sheep and goats. I was washing clothes at the river when lo! my donkeys appeared - at least seven of them were mine, including a foal which was just ten days old when they were taken from the farm. They were just 50 miles from here. I have got them now, though I had a hard fight for them. The horsemen claimed them as loot, but I put the matter into the hands of T. Scanlon, solicitor, with the result I have stated. I would not take £4 each for them. They are making £4 10s a day loading wood.

The laager was broken up when we returned from Hartley, so I was glad to get in a night in bed. I had been sleeping outside for seven weeks and on the Hartley patrol we had to do picket at night. Out of the last three nights, I was on picket two: on Saturday night picket, Sunday off and Monday on and had to march every day. It was too much and I told Captain White I would not do it another night.

Beer is 7s 6d a bottle, whisky 20s a bottle or 1s 6d a glass and big sums are spent over the bars. I hear of working men spending £25 or £26 on liquor in a week or eight days. As soon as things are settled, I shall go and live at the farm; it can be done for half what it costs here. I was going to join the next patrol going out but at present everything is at a standstill for want of bread. We have only three days’ supply. Robinson has just been over from the laager and says they are on half rations…”

BSA Company reports 1896

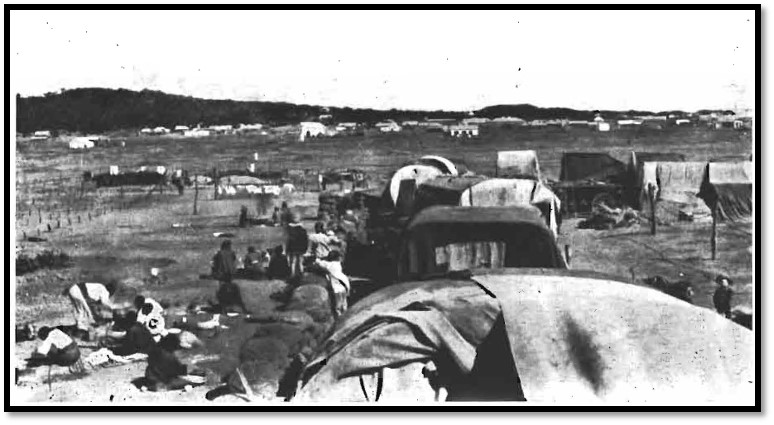

Siege conditions at Salisbury

However, after three or four weeks went by and the district around the town had been cleared by small patrols, the townspeople began to get tired of the inaction and appealed to return to their own homes. This was refused until 17 July when reinforcements arrived from Bulawayo and ensured the presence of trained troops in the town.

Conditions were difficult, food in short supply, but adequate when subject to rationing and despite the cramped, wretched conditions no epidemic developed, which Dr Howland attributes almost entirely to the noble efforts of Dr Fleming and the Dominican Sisters. During the siege period there was only one death, a little girl, Jessie Tapsell who died of bronchitis and three babies were born.[24] Towards the end of six weeks, as the threat of an attack on Salisbury became less likely, the people were allowed to their homes by day, returning to the laager at night. The patients were returned to the hospital in Fourth Street with a day and night guard of troopers.

NAZ: North-west corner of the Salisbury laager with friendly Mashona, barbed wire entanglements on the left and the Kopje in the background

June to 22 July 1896

The section[25] in the BSAC Reports highlights the grave situation in each of the districts of Lomagundi, Hartley, Mtoko, Makoni, Charter, Salisbury, Mazoe, Abercorn, Manicaland, Marandellas and Headlands and the numerous tragic incidents that took place during this period. Many small scale patrols went out seeking survivors and food supplies, but aggressive military operations did not take place until reinforcements had arrived with the return of Beal and the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers from Bulawayo.

Rob Burrett’s article The Selous Road, Ballyhooley Hotel and the Ruwa and Goromonzi Districts in Heritage Publication No 17, 1998, P108–120 gives a dramatic account of the events east of Salisbury at this time.

The relief of the Hartley Hill fort, that Ephraim Nicholson took a part in, took place now that reinforcements had arrived and the relief of the Abercorn party under Duncan with 40 Natal troopers and 25 men from the Salisbury Field Force with a Maxim also went ahead.

A detachment of 70 Grey’s Scouts under Capt Charles White, volunteers from Bulawayo, arrived on 16 July followed the next day by Beal’s force of Rhodesia Horse Volunteers returning to Salisbury. With their return, martial law was cancelled on 22 July.

23 July to 31 December 1896

Further reinforcements were on the way comprised of 380 mounted Infantry under Lieut-Col Alderson, who were originally destined for Bulawayo, but had been diverted to Mashonaland via Beira,[26] also a force of 100 men under Major Watts from Bulawayo that was directed via Charter to liaise with Alderson’s force.

Lt-Col Alderson’s summing up the situation in Mashonaland on his arrival

…The most numerous and the most defiant natives were those in the Hartley district, whose paramount chief was Mashayamombe…Away to the north-west of Hartley was Lomagundi’s country, at which the murders at Eyre’s farm and the Ayrshire mine had been committed. Thirty miles south of Charter was a gentleman

named Umtigesa, who is reported to have said that he was only waiting for the whites to attack him and was not a bit afraid. This individual waited a bit too long as far as his own interests were concerned…

In the Mazoe Valley…were numbers of truculent natives under Chidamba, Amanda and various other chiefs…

Along the banks of the Hunyani [Manyame] and the Ruya [Ruwa] rivers, to the southeast of Salisbury, numerous small chiefs, all of whom were hostile, had their kraals.

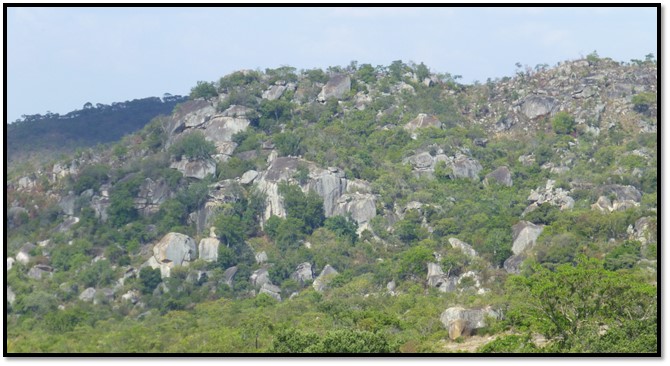

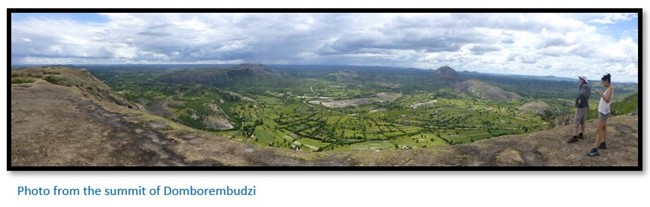

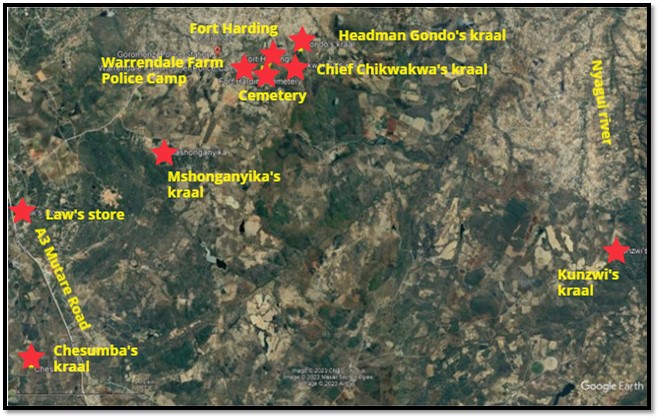

At Chishawasha, some twenty miles north-east of Salisbury, the Jesuit Fathers, assisted by a small guard, were laagered in their mission, the principal chiefs near them being Chikwakwa and Kunzwi, both of whom were hostile and bumptious.

Military operations begin combined with local forces

The first large-scale military operation took place on 3 August when two companies of mounted infantry with artillery and engineer units, two seven-pounders and a Maxim attacked Makoni’s kraal. Although the stockade was stormed, most of the Mashona took refuge in the nearby caves before Alderson’s force moved on.[27] This was a pattern that was to follow in numerous skirmishes in Mashonaland.

Forts to guard the Salisbury – Umtali supply route now began to be built. Fort Haynes was built near Makoni’s kraal, Fort Watts at Devil’s Pass,[28] others were established at Headlands and Marandellas and garrisoned with regular troops.

From 18 September kraals were burnt in the Mazoe Valley by a force of Grey’s Scouts, the Natal troop and Salisbury Horse Volunteers under Duncan, but again many of the Mashona took refuge in the caves from where they could only be dislodged after long and dangerous actions. Supplies in Salisbury had become short with the additional troops and this curtailed operations.

Umtigesa’s kraal in the Charter district was destroyed by Major Jenner and his Imperial troops with the aid of 2,000 friendlies from Victoria.

The next large-scale military operation was the attack on Mashayamombe’s kraal on the Umfuli (Mupfure) river at Hartley Hill. A force of 350 men under Lt-Col Alderson left on 5 October supported by 150 men under Jenner from Charter and 1,000 friendlies. Mashayamombe’s main kraal was attacked on 10 October, a strongly fortified kraal near the Umfuli was attacked and stormed the next day and Chena’s kraal on the southern river bank destroyed by the seven-pounders the following day. As usual, the defenders took to the many caves in the area and were difficult and dangerous to remove.[29]

NAZ: Civilian volunteers on parade at Salisbury, Mashonaland

Operations move to the east of Salisbury

In early November Native Commissioner Campbell met Chief Chikwakwa at his stronghold near Goromonzi. However the Chief was defiant despite facing a strong force of 400 troops and 100 friendlies under Jenner. He was prepared to talk peace, but refused to lay down his arms, and was given time to talk the matter over with his headmen whilst Jenner took his force further east to Kunzwi’s kraal, just west of the Nyagui river for another indaba, but he also refused to lay down his arms.

The Imperial forces leave Mashonaland

On 29 November Jenner left Salisbury for Beira taking 170 of the mounted infantry and two weeks later the remainder followed them. Their main result was to provide military reinforcements to the local units and to secure the supply route to the east, however none of the killers had been brought to justice and the Mashona chiefs were still rebellious.

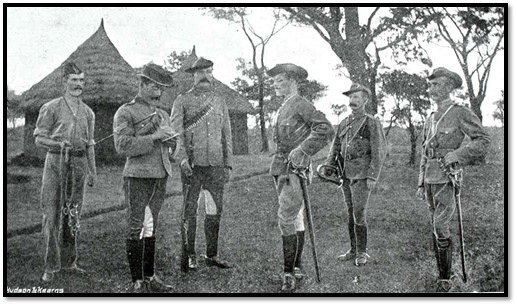

NAZ: Officers of the Mounted Infantry. Standing (L-R) Capt J. Roach, Capt A.J. Godley, Capt P.A. Turner

Seated (L-R) Major Gosling, Lt-Col E.A.H. Alderson, Lieut J.E. Nicholls

However it was felt the situation was such that the new police force, 180 of whom arrived on 10 December could take over the responsibilities under Sir Richard Martin and Col de Moleyns. Detachments were sent to the newly established Fort Martin near Chief Mashayamombe and Fort Harding near Chief Chikwakwa. Local volunteer units such as the Salisbury Field Force assisted until the police were at full strength when they were finally disbanded.

It was in operations undertaken by this new police force, the British South Africa Police, that William George Irwin was killed at Kunzwi’s kraal.

1 January to 27 October 1897[30]

Operations under the police force now became more aggressive. When the tracks of cattle rustlers were traced to Simbanoota’s kraal, 13 miles south of Salisbury, Lieut Harding took a police patrol. The chief refused to talk and so the kraal was attacked and burnt.

Then news arrived that Chief Manyese’s men had attacked and burnt three kraals, killing 16 inhabitants and carrying off women, cattle and goods.

Army and Navy Illustrated catalogue: British South Africa Police Officers

A Police patrol went to Charter under Major Gosling where it was joined by the Native Commissioner and his police and volunteers making a total of 100. After a night march, the kraal of Chief Tshagora was reached and attacked at dawn followed by Marambwa’s kraal. Both were burnt, 27 defenders were killed and 70 captured women freed and guns and stock seized.

This skirmish was described by Police Trooper Pilcher to his cousin T.B. Ferguson[31]

“A day or two after I wrote to you we were ordered out on patrol; We were away from here just a fortnight and had a very enjoyable trip. We were sent out to attack a kraal and burn it down, and we succeeded in doing so; in fact they reckon it was the most successful patrol that went out during the rebellion. We arrived at the scene at 5:15 in the morning, after marching all night, and it was raining heavens hard. We dismounted about 3 miles from the kraal and then had to march single file up a mountain covered with stones, the black police in front. After we got to the top we halted for a minute or so, when the scouts gave the signal and we descended about 300 yards, when away went the volleys from the front and then we got the order to "double," and away we went right up to the kraal and fired three volleys.

We were then ordered to charge the wall, and over we went, and the natives were off down the mountain like smoke, the "Black Watch" after them. It was a terrible surprise to them as they did not suspect us after the heavy rain. There were 27 natives killed and we got a lot of sheep and goats. After the "ceasefire" sounded there was a rush into the huts after loot— native war implements, fowls, and anything that we could lay hands on. We were allowed about an hour or so and then told to fire the huts. It was a very pretty scene in the middle of the range with all the huts on fire. We then had a couple of hours' spell, discussing the various incidents that occurred, when we started on our return to the place where the waggons were camped. No sooner had we arrived and had some "scoff" when down came the rain in torrents, and all night we were camped in about a foot of water and mud.

The next morning we started again at 9 o'clock and marched on to another kraal and attacked it about mid-day, but the natives had just gone for their lives. We had some fun here chasing fowls, and got about 150 of them, some of which we started to roast for dinner; the rest we brought back to camp and had a great feed the next morning. We also captured more goats and sheep and also a young bull. I have sent a paper home with the account of the patrol, so you will be able to see it for yourself. We got great praise from Earl Grey and he paid particular notice to us Australians, which has caused a lot of jealousy among the other men. Will Maynard, another young Gympie and I have made up our minds pretty well to take a trip to the "old country" at the end of our term, before returning to Australia as we are so near we had better have a good trip while we are about it. With regards to self and all inquiring friends, — I am your affectionate cousin T. Pilcher”

A further patrol took place to Chief Seki’s off the Umtali road on 22 January and a dawn attack captured the kraal where a large amount of goods looted from road convoys was discovered, including the Salisbury Cathedral’s communion plate.

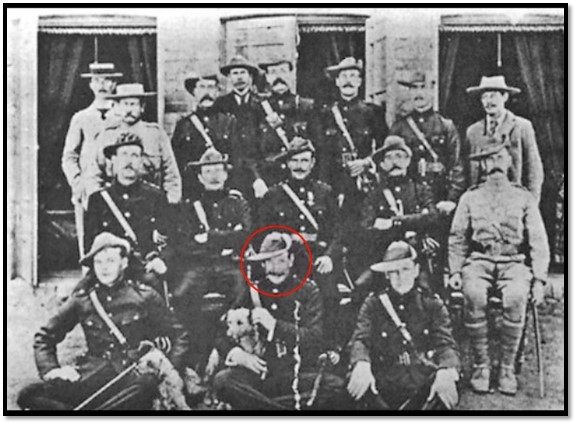

National Archives of Zimbabwe: Officers of the Mashonaland Division, BSA Police 1897

Standing (L-R): Capt Wilson-Fox (attached) Capt Brabant (attached) Captain McQueen,

Captain Ashe (attached) Lieut Mundell, Lieut Norton-Griffiths, Lieut Money, Commander Tyndale-Biscoe

Seated (L-R): Capt Roach, Major Gosling, Lt-Col the Hon de Moleyns, Major Hopper, Captain Walshe

Front (L-R): Lieut Ellett, Captain Harding (with circle) Lieut Godley

Operations continue east of Salisbury

Harding, Father Biehler from Chishawasha Mission and Howard made another visit to Chief Chikwakwa’s to try and persuade him to lay down arms. He writes that they sat at a distance from the kraal and waited, but nothing happened. “We could not sit all day looking at each other, so finally Father Biehler, Howard and I, leaving our horses and revolvers behind, began walking in an assumed manner along a well-worn native footpath towards the kraal…we continued till within three or four hundred yards from the base of the hill. Here, finding a huge rock where in more peaceful times than native children sat and played their games, we again halted and lighted our cigarettes.

Now I realised the value of the Jesuit Father, for at my request, he in the clearest of Shona, yelled to the restless natives in front of us, that we had not come out to fight, but to talk peace and in proof of what we said, we pointed to our armed troopers whom we had left behind and who could be seen resting in the distant veldt. The natives replied, ‘Come closer, we cannot hear what you say.’ Reluctantly, we went nearer

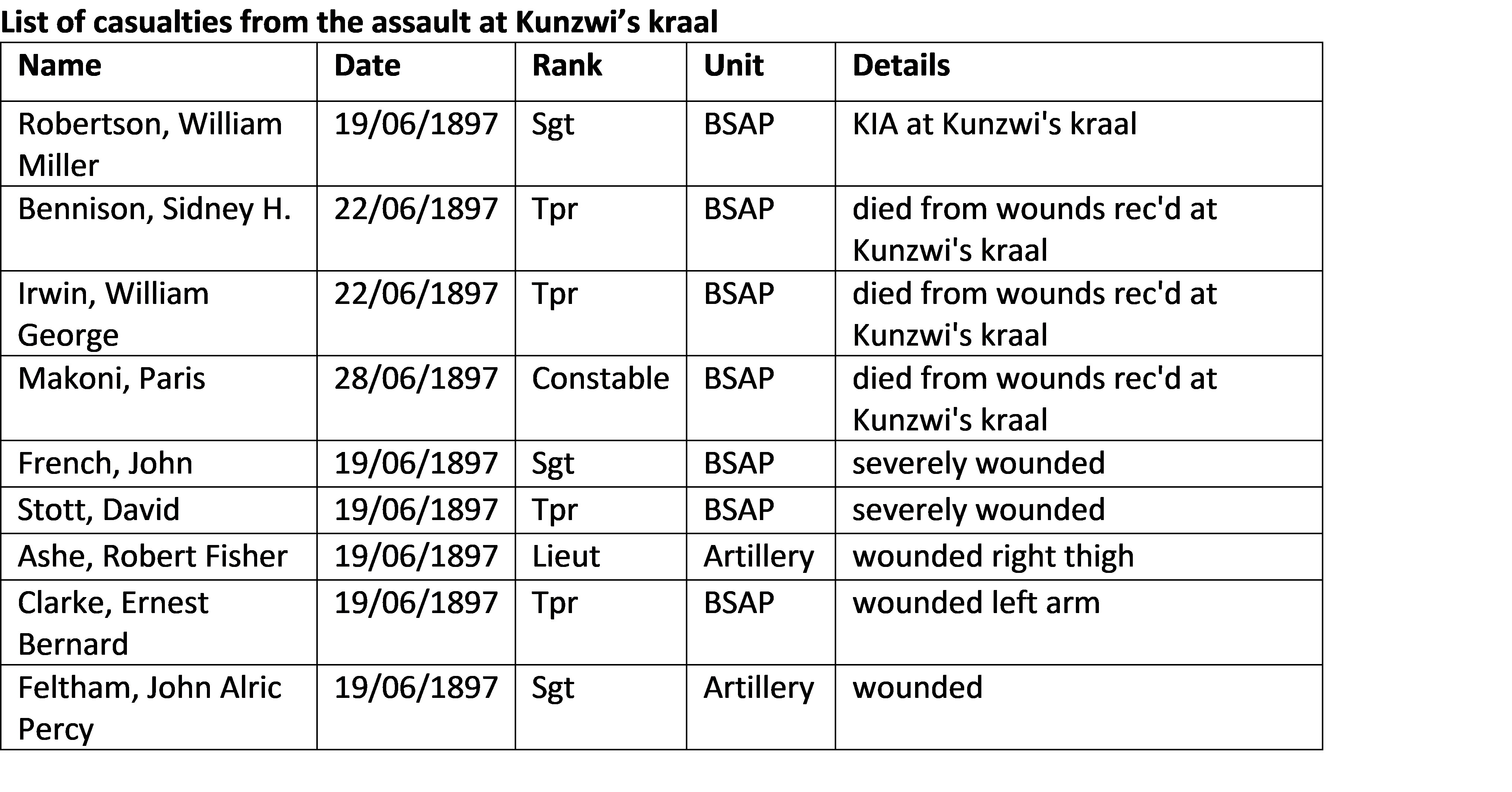

W.H. Robertson, S.H. Bennison, W.G. Irwin, all casualties from the assault on Kunzwi’s kraal, are buried at the Fort Harding Cemetery, as most probably is also Trooper A.J. Hales who died of fever on 5/12/1897 at the police post that was established at Kunzwi’s kraal.

Beside Paris Makoni who died of his wounds sometime after the event, another two Police Constables were killed in action and eight others wounded.

Fort Harding Cemetery

The details on the two remaining memorial nameplates have not survived, so it is not possible to identify where William George Irwin is buried, within this small cemetery. They are not the standard memorial crosses marked by the Loyal Women’s Guild (LWG) so presumably the grave memorials were intact and legible in 1910-12 and the LWG saw no need to order new ones. In a way it is very fitting that his epitaph has survived in the churchyard of St. Mary Magdalene’s Church that Berenice Baynham recorded.

Reports from the East Cumberland News

The newspaper reported on 3 July 1897 that John Hill Irwin, eldest son of the late Lieutenant Colonel Fox Irwin, and nephew of the High Sheriff of Cumberland, had been killed in the attack on Kunzwi’s kraal in Mashonaland; but on Wednesday his mother, who lives in Jersey, received a telegram from Fort Salisbury, stating that he was safe.

On 10 July the newspaper reported that the Colonial Office had replied "Man killed was George Irwin, not John Hill Irwin. Much regret mistake." The report presumed that the deceased was William George Irwin, who was a solicitor with Messrs Wannop and Westmorland, until December last, when he left for Africa. He was a son of the late Mr Irwin, yeoman, Little Corby.

On 17 July the East Cumberland News reported, A Carlisle man killed in Rhodesia

Trooper Irwin whose death has been reported as taking place in an attack on Kunzwi’s Kraal in Northern Mashonaland, was Mr William George Irwin, late of No. 1, Cavendish Place, Carlisle, and son of the late Mr George Irwin, Little Corby. Mr Irwin, who had previously been a solicitor with Messrs Wannop and Westmorland, left Carlisle for South Africa last December. He spent some time at Muizenberg, about 15 miles from Cape Town, and on April 8th joined the Chartered Company's Police, and sailed the next day for Beira in the Hawarden Castle. The journey from Cape Town to Fort Salisbury occupied six weeks, and Mr Irwin arrived at Fort Salisbury on May 22nd. The Beira Railway ends at Chimoio, which is 300 miles from Salisbury, and this part of Rhodesia still seems to be unsettled, as during the journey across country the troopers slept with their rifles at their sides. Mr Irwin's last letter to his sister, Mrs Carruthers, of Bridge of Allan, which was received on Monday, July 5th, bears the date May 31st. After describing his journey to Salisbury, he says:—"We have just had medical inspection, and we go out to-morrow on patrol against a Chief called Kunzi. I will write you when I return and let you know how I get on. I cannot write more just now, as I have been warned for stables and must get on duty." His death took place on the 20th of June from wounds received on the 19th. The Colonial authorities are of opinion that the telegram received from the High Commissioner for South Africa on July 3rd leaves no doubt that the trooper killed was Mrs Carruthers' brother and have written by the mail of July 10th for further particulars concerning his death. Mr Irwin was well-known in Carlisle, he being a prominent member of both the cricket and football clubs; and the news of his untimely end has been received with great regret by a wide circle of friends.

Official Reports

The following telegram from Sir Alfred Milner to Mr Chamberlain was issued from the Colonial Office yesterday morning:

"June 22.—Martin reports Gosling has captured and burnt Kunzwi’s Kraal.

Casualties.—British South Africa Police: Killed: Sergeant William Miller Robertson. Dangerously wounded: Sergeant John French, Troopers John Hill Irwin and Sidney Bennison. Severely wounded: Trooper Stolt. Slightly wounded: Sub-Inspector Ashe and Trooper Bernard Clark. Two native contingent killed, nine wounded. Sergeant French specially mentioned for gallant conduct."

Sir Alfred Milner, High Commissioner at the Cape, who on Wednesday telegraphed informing Mr. Chamberlain of further fighting in Mashonaland and the casualties which resulted, yesterday supplemented his despatch by a message as follows: "Referring to my former telegram I regret to report that Troopers Irwin and Bennison died June 22. These troopers were returned as wounded in the original despatch.”

(Morning Post, Friday 25th June 1897)

A telegram from Fort Salisbury, dated July 6, announced that Major Gosling and the police have returned from Kunzwi’s. They were entertained at a public luncheon on arriving back. Responding to the toast of his health, Sir Richard Martin, the commandant of police in Rhodesia, said that now the demolition of Kunzwi’s had been accomplished, he anticipated very little trouble from the other rebels near Salisbury. The next duty of the troops would be to clear Hunyani and Umtali of rebels. After that the police, hussars, and volunteers would combine to strike a decisive blow against Mashingombi. (Mashayamombe)

(Belfast News-Letter, Friday 9th July 1897)

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Berenice Baynham who drew my attention to the memorial inscription at St. Mary Magdalene’s Church, Hayton and searched out and sent me all the above contemporary newspaper articles based on 1896 written letters by the young men who were then serving in the British South Africa Company Police.

References

E.A. H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896. Books of Rhodesia, Vol 20, Bulawayo 1971

R. Burrett. The Selous Road, Ballyhooley Hotel and the Ruwa and Goromonzi Districts in Heritage Publication No 17, 1998, P108–120

J.A. Edwards. The Lomagundi District, an historical sketch. The Rhodesiana Society Publication No 7, 1962

C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall Ltd, London, 1933

H. Marshall Hole. Mashonaland section of The ’96 Rebellions; The British South Africa Company Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia, 1896-7. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 2. Bulawayo 1975

H. Marshall Hole. Old Rhodesian Days. Books of Rhodesia Silver Series, Vol 8, Bulawayo 1976

R. Howland. The Laager Hospital in Salisbury (1896) September 1965, The Central African Journal of Medicine

C. Van Onselen. Reactions to Rinderpest in Southern Africa 1896-97. Journal of African History, XIII, 3 (1972) P473

Notes

[1] Berenice Baynham drew my attention to the memorial inscription and searched out contemporary newspaper articles of the event – see Acknowledgements below

[2] Hugh Marshall Hole was Civil Commissioner and Magistrate of Salisbury

[3] Old Rhodesian Days, P104

[4] There is a detailed article of the Jameson Raid under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[5] Jameson was sentenced to fifteen months in Holloway gaol, but because of ill-health only served four months. Willoughby was sentenced to ten months imprisonment, R. White to seven months, his brother H.F. White to five months, as were R. Grey and C. Coventry. All terms were without hard labour. The officers were all stripped of their ranks, but their commissions were later restored in recognition of outstanding service in other fields of action!

The members of the reform committee based in Johannesburg were found guilty of treason by a Transvaal Republic court and sentenced to hanging. This was then commuted to fifteen years gaol, before their release in June 1896 after paying heavy fines. The British South Africa Company paid the Transvaal Republic almost one million pounds.

[6] The ’96 Rebellions, P122

[7] Rinderpest killed enormous numbers of cattle and game in Africa. It was evident in Somaliland in 1889 and moved rapidly south to Uganda in 1890. In the second half of 1892 Lugard wrote from Northern Rhodesia. “I had no evidence that the disease had attacked the wild game until I arrived at the south end of Lake Mweru. Here enormous quantities died. At the time of my passing in October 1892, the plague was at its height, dead or dying beasts were all around.” The Zambesi river proved an effective barrier until February 1896 when it was reported in Matabeleland. C. van Onselen

[8] See The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[9] The Rinderpest outbreak only came to an end when widespread inoculation

was carried out starting in the Cape after 1897

[10] There was a wide-spread perception amongst the Matabele people that the Rinderpest regulations were part of another round of cattle confiscation, as had previously occurred in 1894 after the invasion of Matabeleland

[11] Those recruited to the Pioneer Column were not paid salaries, but promised 1,500 morgen (3,175 acres) farms and the right to prospect for ten gold claims in return for their participation

[12] Marshall Hall notes (P101) that the removal of most of the Police force outside the country aroused very little interest in Mashonaland as there were rumours the Chartered Company was taking over the administration of the Bechuanaland Protectorate and their transfer seemed a normal precaution against possible disturbances from the Bamangwato.

[13] The Lomagundi District, an historical sketch, P11-12

[14] The Lomagundi district itself is estimated to cover 57,441 sq. kms (22, 178 sq. miles)

[15] For details of these events see the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

[16] The Lomagundi District, an historical sketch, P12

[17] Far Bugles P49, Mr and Mrs Norton, their child Dorothy, the nurse Miss Fairweather and farm supervisors Harry Gravener and James Alexander are all buried in the same spot in what is now the Morton Jaffray water treatment plant

[18] See the article Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery and Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[19] See the articles the Siege of Deary’s Store at Abercorn, June 21st – July 13th, 1896, and also the June 1896 Mazoe Patrol Skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers, both articles under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[20] See the article Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental telegraph Co under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[21] Situated where the Central Police Station stands today, close to the junction of the Causeway (Julius Nyerere Way) and Railway Avenue (Kenneth Kaunda Avenue)

[22] The Laager Hospital in Salisbury (1896) P256-7

[23] On the Hartley Hill patrol, Trooper Gwillim and two Zulus were killed, Troopers Kerr, Arnott and Lee and two Zulus wounded.

[24] The Laager Hospital in Salisbury (1896) P259

[25] Compiled by Marshall Hole, Civil Commissioner and Magistrate at Salisbury

[26] For the actions carried out by Lt-Col Alderson and the Mounted Infantry see the articles Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[27] At Makoni’s kraal those killed in action included Capt A.E. Haynes, Royal Engineers, Pte W. Wickham, Royal Irish Regt, Pte S. Vickers, 3rd Battalion King’s Royal Rifles; three others were severely wounded and one slightly wounded

[28] See the article Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[29] See the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[30] This section was written by Percy Inskipp, the British South Africa Company under-secretary

[31] The following letter from Salisbury dated 24 January 1897 was published in The Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette under the title ‘A Gympie in South Africa’ on Tuesday 23 March 1897