Home >

Mashonaland East >

Colin Harding – the man in charge of the execution of Chief Chingaira Makoni – his life and career in early Rhodesia

Colin Harding – the man in charge of the execution of Chief Chingaira Makoni – his life and career in early Rhodesia

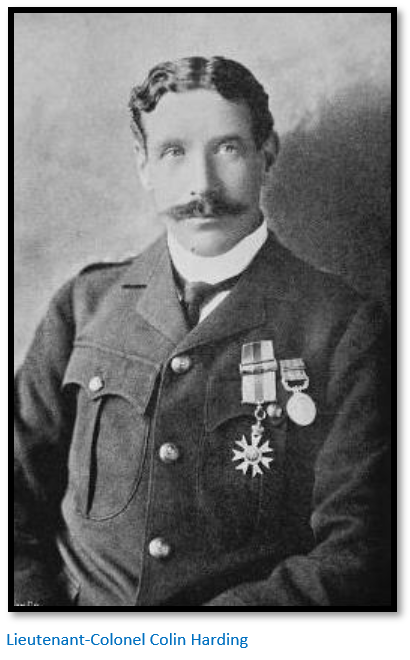

Edwin Colin Harding had a very distinguished career being promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and awarded the C.M.G. Companion (of the Order Of) St Michael and St George and the DSO Distinguished Service Order.

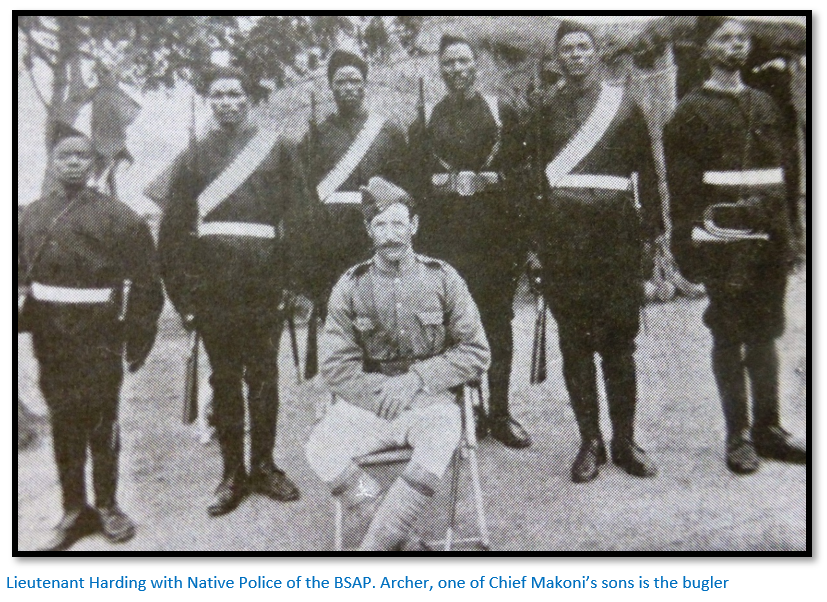

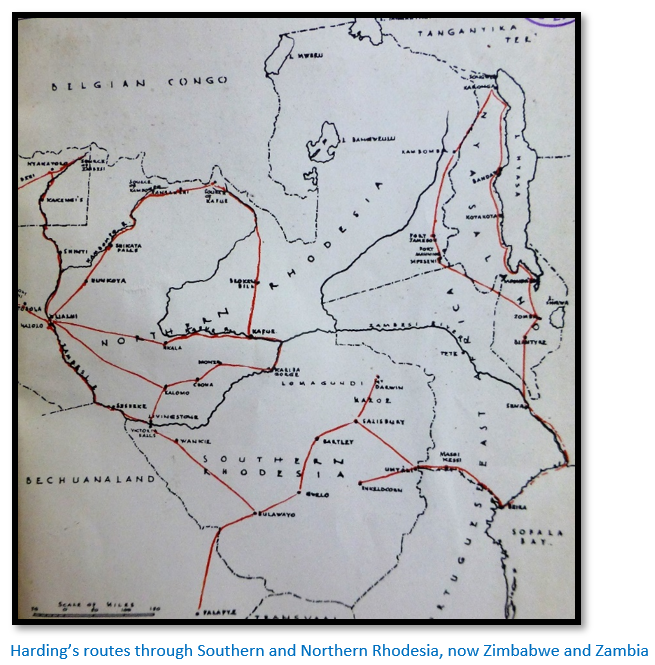

He began his career in Matabeleland in 1894 and was in Mashonaland during the 1896-7 Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga when he was promoted to Inspector and in command of the Native Police and twice mentioned in despatches. This article concentrates on this period of his life with a brief summary of his later career.

In 1898 he was posted to Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia to command and re-organise the Barotse Native Police force before being appointed in 1899 as acting Resident Commissioner in Barotseland. On the return of the Resident commissioner, Robert Coryndon, he was promoted to Colonel.

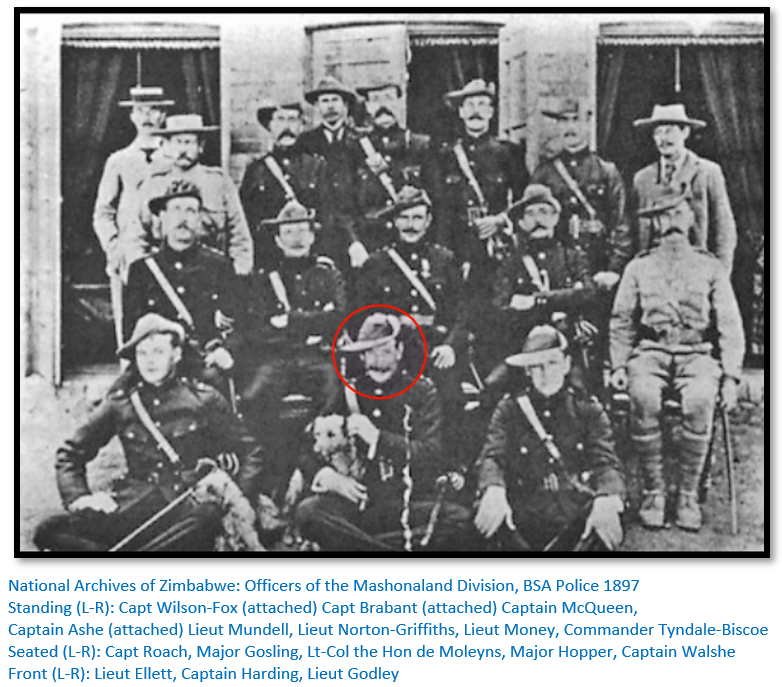

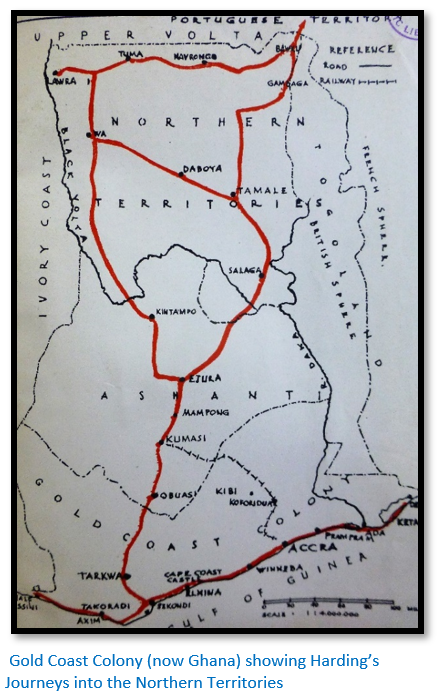

In 1909 he was a District Commissioner in the Gold Coast, now Ghana. On leave in England in August 1914 he helped raise the 2nd King Edward’s Horse and went to France with them in May 1915 where he succeeded his old BSAP colleague John Norton Griffiths as second-in-command and was under the command of another old colleague from Mashonaland, E.A.H. Alderson, now a Lieutenant-General. He fought at the front until September 1916 when hospitalised with appendicitis and deemed unfit for further service at the front was on his retirement awarded the DSO.

In 1917 he returned to the Gold Coast to serve as a Provincial Commissioner and member of the Legislative Council until his final retirement in August 1921. Married Margaret (née Porter) in 1899. Died on 3 January 1939 aged 75 years and buried at the Church of St Catherine’s, Montacute in Somerset.

Early days

Edwin Colin Harding was born on 15 August 1863, a son of Charles Harding of Abbey Farm, Montacute, Somerset. Educated privately, until the age of thirty years, he seems to have done little but hunt with the hounds on his pony Glover. However, the death of his father revealed the family to be in dire financial straits: “the unwelcome fact that neither myself nor other members of the family were as opulent as anticipated…in fact, the final settlement of our estate proved that our financial position was not only unpromising, but desperate and it left us with no option but to give up a home which we had for many years loved to distraction and the society of a delightful circle of friends and start life over again.”[i]

“Neither I nor my brothers had any profession, nor yet the means to qualify for one or to acquire a business…hunting teaches a man a lot, much more than a non-hunting man realises. One thing it taught me was, that if you had to jump a five-barred gate with a bad take-off or a fifteen-foot brook with sticky banks, the obstacle did not grow less by contemplation.”

On one dark January morning in 1894 Harding, figuratively speaking jumped the objectionable gate and left his home for South Africa. The old farm hands were arriving at work as he climbed into the wagon to take him to the railway station. They shook his hand with tearful eyes, and each made encouraging remarks that as he was going to foreign parts and they should probably never meet again.

His sister, who was nursing, saw him off at Southampton as a steerage passenger[ii] on S.S. German and he found he was sharing a cabin with eight others. He says, except for the most fastidious, no one removed either boots or stockings. He woke up in the midst of a violent storm, everyone was sea-sick, the cabin “was reeking with nauseating stuffiness and filth.” The first port was Lisbon…he never spoke to a fellow-passenger and his first decent meal of fish and fruit was at Lisbon four days later. Then a brief stop at Madeira with the next stop at Cape Town.

Meets an old friend at Cape Town and they journey to Bulawayo

At Bulawayo he had a letter from an old hunting friend named Toms who was arriving on the next boat en route for Matabeleland and asked Harding to accompany him. They took the train to Johannesburg and soon left on a small ox-wagon pulled by six oxen and reached Bulawayo after six weeks trekking.

Here he took stock of his rather desperate financial position. He was in a strange country with just one friend, with no trade or profession and with only ten pounds in his pocket. All food was at siege prices, beer being 4 shillings per bottle. Toms left with another man on a prospecting tour, to meet his daily needs Harding sold his saddle, bridle and breeches, plus a shot gun.

Night after night he returned to his room both tired and hungry “when many miners and successful prospectors were reeling in the streets of Bulawayo, spending the proceeds of their farming and mining rights in debauchery and in drink.”[iii]

At last, a builder offered to take him on as a sawyer’s mate for £3 a week. Harding says he can confirm from experience that it is the under-sawyer who ‘gets all the kicks and none of the ha-pence.’ However, while attempting to demonstrate to his boss that he knew the duties of a top-sawyer, he fell ten feet into the saw-pit and damaged his ankle leaving him hors-de-combat for several days.

His next position as a second-rate bricklayer also ended badly and soon any unsatisfactory building in Bulawayo was being instantly labelled: “this is the house that Harding built.” This led to a partnership with a friend to paint shop windows and doors of Bulawayo stores “a job in most cases overdue, but very few storekeepers could be induced to see this” and the partnership dissolved.

Rising in the world as a solicitor’s clerk

His next appointment was as Mr Gatehouse’s Chief clerk. “That I was the only man in the office did not in the least rob me of the importance that I was ‘Chief’ clerk.” The office was a small, corrugated house with two small rooms, one of which was allocated to the staff. His first day was Saturday and Gatehouse arrived two hours later and gave some instruction in the work, which involved dealing in the sale of land and stores, before leaving and saying he would be back on Monday morning.

A prospector came in requesting help to collect a £20 debt though he had no evidence to support his claim. Harding made him sign an affidavit and copied a demand note from the letter book and charged him two guineas before bowing him out. With a black eye he returned in about an hour, paid with great reluctance the two guineas and pointed with shaky forefinger to his disfigured eye remarked: “This is the only thing I got out of the blighter,” and honestly, I was not surprised.[iv]

With no cashbox he slid the two guineas into his pocket and went out for lunch where he met a friend, Hamilton, who told him that afternoon he was riding in a race on a course laid out in one of the main streets of Bulawayo. After lunch he walked to the race site where “amidst much shouting and recrimination, people were betting and arguing right and left.” His friend’s grey looked a sure winner over the half-mile distance and Harding placed a bet using the two guinea fee. Hamilton made an excellent start and would have won ‘hands down’ had not a partisan of the other horse fired his revolver as the favourite was passing his store. The grey swerved, crossed a leg and came down a most awful purler with Hamilton underneath, but fortunately unhurt. When he informed Gatehouse on Monday morning what had become of his two guineas, he was told he was “damn smart to have ever earned it.”

He stayed some time working with Gatehouse and learned much about the law and writes that the mixed feeling of hostility and friendship was symbolical of the atmosphere in Bulawayo in 1895-6. He saw men fight with ungloved hands until they could hardly stand; the victor would take his opponent to the nearest store and attend to his many bruises before buying him a clean shirt and washing out his bleeding mouth with a bottle of Pomeroy.[v] Two days later they would set off, the best of friends, on a prospecting trip.

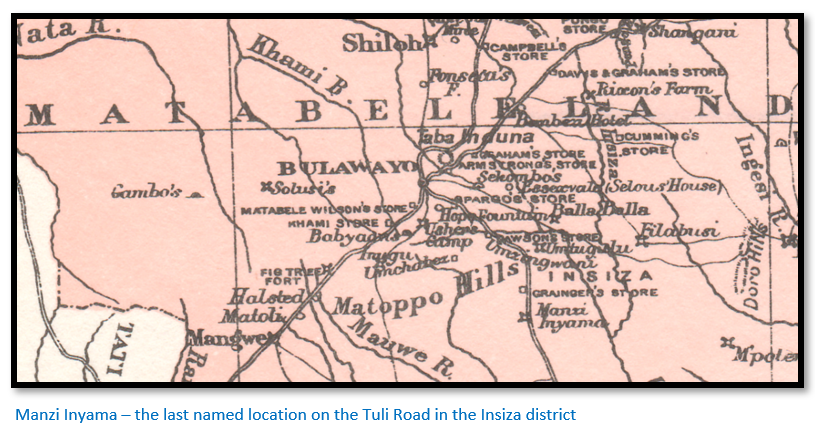

Quits office work for gold mining at Manzi Inyama, south of Bulawayo

Towards the end of 1895 Harding set goodbye to his genial employer Gatehouse and accompanied Hamilton to the small mining camp at Manzi Inyama about 80 kms (50 miles) south of Bulawayo. The local headman sent his three sons to help sink a prospecting shaft to connect with the gold bearing reef 14 metres (40 – 50 feet) underground. He also made goatskin bellows for the small portable forge on which they sharpened the drills and picks. His sons were always cheerful and shared the hardships of the rainy season without complaint and rejoiced when Harding took his gun and brought back an antelope or guinea fowl for the pot.

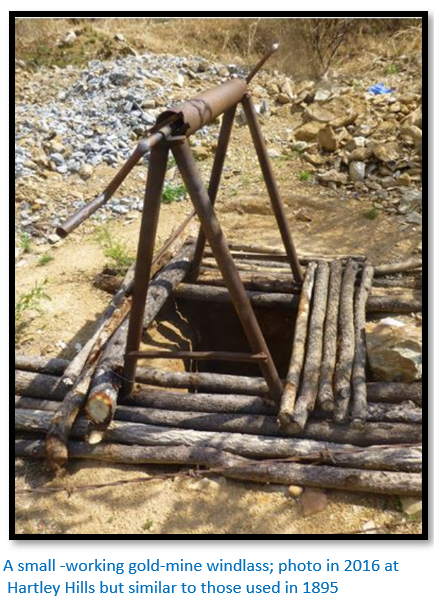

Harding believed then that digging out gold ought to be much the same as digging out a fox…they began to dig the shaft and built a windlass for lifting out the soil. Eventually they struck rock which required dynamite. His workers would watch Harding prepare the charges, see him insert the time fuse with detonator attached, but refused to lower him down the shaft. He had to prepare a demonstration to enable them to recognize the value of the safety fuse that gave them time to get to safety before the charge exploded.

Finally, they agreed to lower him down the shaft with the charges and once the charges were lit hauled him to the surface at great speed before bunking for cover under a rock or tree and then watch the dislodged rocks shoot up into the air and fall with a thud to the ground.

Now convinced they were not in the least afraid of “dynamitey” they would take home-made snuff whilst watching the poisonous dynamite fumes disperse in the air.

Three weeks later they were down 12 metres (40 feet) and had drilled five holes. As water began to collect Harding was lowered down the shaft to prepare the charges by the light of a tallow candle stuck on a nearby rock. The holes were deeper than usual, and the fuses just reached the top of each hole and after checking his men were ready to wind him to the surface, he lit the five fuses. Then with one foot in the bucket he was hauled up about 10 feet until suddenly he was dropped to the bottom of the shaft. Although somewhat stunned, he yelled to be pulled up and was told: “The windlass is skellum and will not work.”

Clearly the rope had broken, normally the thing to do would be to cut the fuses, but they were too short, and it was impossible to reach them, although he could hear them “fizzing” away. He groped madly in the dark for the rope and finally felt the end…sprang up and managed to get a grip before he was jerked upwards hoping the dynamite would not yet explode. Soon he heard the agitated voices of his small crew urging him to make haste and at the mouth of the shaft eager arms dragged him over the lip before the dynamite exploded. They were all covered in dirt and Harding’s legs hit by small loose stones, but they had saved his life and Harding says here when: “death was staring me in the face, I first learned to appreciate the pluck and devotion of the African native.”[vi]

Sometime later he caught fever and walked the 24 kms (15 miles) to Grainger’s store where he lay ill for a fortnight before the storekeeper then went down with fever and Harding took over his storekeeping duties!

In another mining venture his assistant Sullivan returned from the closest store after a weekend’s drinking still the worse for liquor and insisted on lighting the charges for six or seven prepared drill holes, despite Harding’s protests. He was watched at the bottom of the shaft preparing the fuses with shaky hands. He lit one, then another. Then he was heard to say: “I can’t find the ******* fuse” which was eventually found. The shaft was now full of black smoke from burning fuses and Harding yelled for him to come up immediately. He replied in a drunken voice: “Don’t be in such a ******* hurry!” Finally, the pull of the rope came, and he was hauled up just in time before the charges went off showering them all in dust and stones. Sullivan and Harding then parted company.

June 1895 – absence of European British South Africa Company Police in Matabeleland

Harding says it was noticeable that there were no mounted police in the country: “there were ominous signs the Chartered Company were organizing an expedition for some unknown work down country.” A body of volunteers was raised to take their place. “The native too, seemed restless and aggressive.”[vii]

Then he heard from his old friend the storekeeper that two ladies were coming up on a shooting expedition and asked if they could use Harding’s camp-site. He had not spoken to a woman since leaving S.S. German a year before and speculated that they would be two old Dutch vrouws but was delighted when two young Englishwomen rode into camp followed later by their wagon and driver.

They were Miss De Trafford and Miss Amy Norton, who had come up to visit Miss Norton’s brother farming on the Hunyani, now Manyame river, after whom Norton, the town, was named after the entire family were killed in the First Chimurenga in 1896.[viii] They stayed a week with Harding and during that time he received a letter suggesting he might be needed in the Rhodesia Horse in which he was a corporal.[ix]

The Jameson Raid had just taken place and a telegram had been received at Bulawayo from Jameson which was read out by Spreckley and Napier telling the Rhodesia Horse to be ready to move to Johannesburg. Harding says he will never forget the excitement this telegram caused, but first Miss Norton had to be persuaded that their trip to Mashonaland was no longer viable and after selling the wagon and horses they left by Zeederberg coach with its ten mules for Mafeking.

At the last moment Harding decided to accompany them. The coach: “seldom stopped except to change mules” when a quick “snack was taken of badly-cooked food at a small wayside store…sleep there was none and any repose we obtained during the whole journey was snatched in a sitting position with your head resting on the shoulder of the adjacent passenger.”[x]

After Mafeking they were stopped and searched: “all our luggage was subject to the minutest scrutiny; and I as an old Rhodesian, came in for a lot of hostile criticism, when my revolver was confiscated, and my name associated with unnecessary adjectives delivered at short range by Boer officials.”

Outbreak in late March 1896 of the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela followed by the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga in June 1896

Harding first learnt of the rebellion from the newspapers whilst staying with his mother. Many of his former friends at Manzi Inyama were killed, his old camp burnt down.

He met Miss Norton in London who had just heard of her brother’s murder: “she asked me to investigate the awful calamity which had nearly broken the heart of her beloved mother.” Harding immediately made up his mind to go to Mashonaland, instead of Matabeleland, but: “Alas, Miss Norton and I never met again.” Harding’s description of his visit to Porta farm, the scene of the Norton’s murder is described at the end of this article.

As in Bulawayo, so in Salisbury the authorities in the form of the British South Africa Company were totally unprepared for the mass of murders which took place in Mashonaland, for here the permanent police force had been appropriated by Jameson and the Rhodesia Horse had been sent to Matabeleland under Col. Beale and weakened their defences even further.[xi]

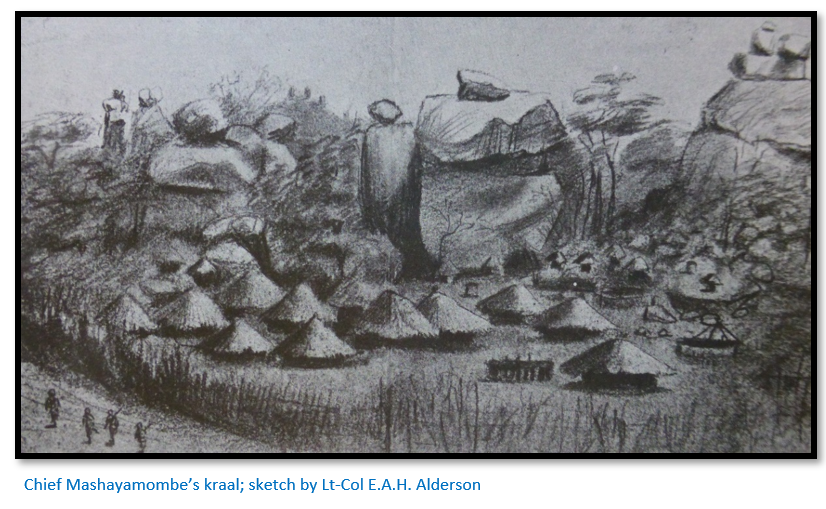

The first news of the rebellion came on 15 June when a native came into Salisbury and reported the murder of Tate and Koefoed together with four natives at Beatrice mine by Chief Mashayamombe’s men. Judge Vincent quickly had the Natal Troop on its way to Matabeleland despatched from Charter to Salisbury and Beale’s forces were recalled from Bulawayo.

Harding returns from England

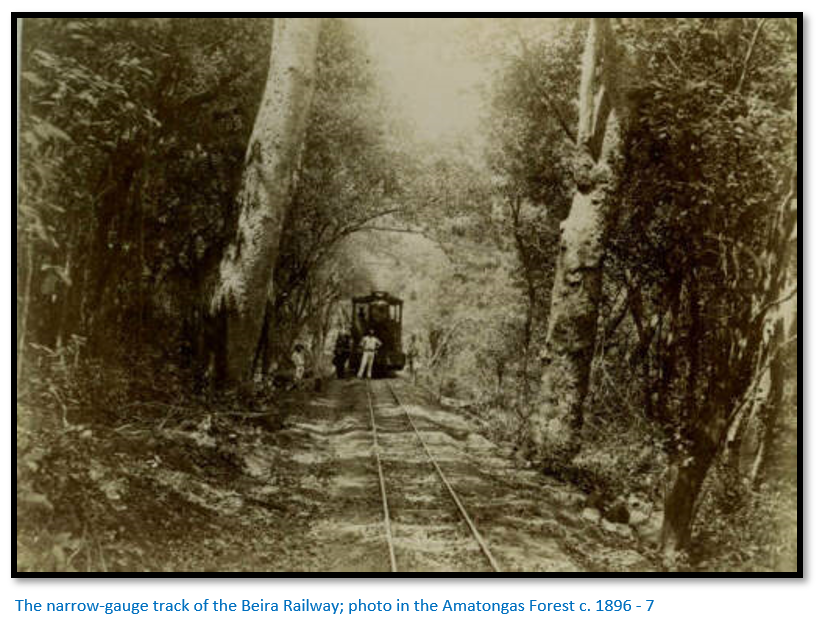

An easy passage saw Harding and his friend Robin Grey to Cape Town, and it was arranged that they would accompany Captain Armstrong on a small coastal steamer to Beira taking horses as remounts and mules for the forces. Harding says they preferred looking after the horses: “for whereas a horse would generally kick straight and bite rarely, the mule would kick at every conceivable angle without any warning or pretext and generally bite if there was no possible chance of hitting you with his hind legs.”[xii]

Armstrong asked them to accompany him and his animals to Salisbury, now Harare. Because of the tsetse-fly the train to Chimoio had its trucks protected with wire gauze; there were many stoppages on the narrow gauge line of 2 feet 6 inches (76 cms) with its tight curves and steep gradients and they often got out and pushed.

At Chimoio the horses were detrained, Grey became ill with dysentery and Armstrong and Harding were left in charge of thirty horses. Rifles were left behind as too cumbersome: “what with revolver, water-bottle, haversack, nose bag and great coat badly folded on the pummel of the saddle, we looked more like an over-hung Christmas tree than two mounted police.”

No sooner had they started than the horses stampeded out of sight and it took the whole day to round them up. Harding told Armstrong it was no good tying them up in fours, whilst Armstrong criticised him for giving the horses too many oats! Eventually Harding led the way with the principal offender of the stampede firmly held by the halter and the others followed meekly until they finally reached Old Umtali (present-day site of the United Methodist Church and Hartzell High School, adjacent to Africa University campus)

Here they were allowed to keep a horse apiece, the remainder were handed over to Major C.N. Watts of the 2nd West Riding Regiment, now part of the Matabeland Relief Force and they parted firm friends with Armstrong who went back to his old role as Native Commissioner. [The article the Selous Road under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com has a short biography on William Leslie Armstrong]

Harding joins Major Watts’ attack on Chief Chingaira Makoni’s stronghold at Gwindingwi Mountain

Harding’s plan had been to investigate the killings at the Norton’s Porta farm, but Major Watts persuaded Grey and Harding to stay as gallopers…he says they needed little persuasion.[xiii]

Chief Makoni was strongly opposed to British South Africa Company rule and had been directly and indirectly responsible for many of the killings in Macheke / Headlands and was believed to be the ringleader of the rebellion in the area. Lt-Col. E.A.H. Alderson had attacked his stronghold after a night march from Fort Haynes on 3 August 1896 but was unable to extricate the Chief and his followers from the deep caves of Gwindingwi Mountain into which they had retreated and moved onto Salisbury [See the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Chief Makoni threatened the communications and transport between Salisbury and Old Umtali and the task of keeping the route open had been given to Major Watts who had under his command 132 Umtali Volunteers under Major Hamilton Browne and a 50-strong detachment of the West Riding Regiment from the Matabeleland Relief Force and the old seven-pounder gun stationed at Old Umtali.

Chief Makoni sent Watts a message on the 27 August 1896 saying he would surrender the next day; but failed to appear and on the 30 August another night attack was made on the Chief’s kraal, but they were given away by the rumble of the seven-pounders’ wheels and heard the warning cries of the outposts. A simultaneous attack from all sides was made on the kraal, which was soon captured, but yet again the Chief and his followers disappeared into the warren of caves in the mountain.

Over the next few days, Watts bombarded the main entrance to the cave with the seven pounder and captured some fighters who tried to escape. Harding writes that on duty early one morning he saw a warrior armed with a gun and assegai trying to slip away. “We played hide and seek round many of the huge boulders. His one idea was to halt and get a shot at me and my idea was to keep him on the move and thus prevent his knavish tricks. Finally, I got him in the open. I gave chase and eventually caught him. A struggle now ensued before he had time to stab or fire, I flung him to the ground and deprived them of his arms.”[xiv]

Chief Makoni’s men kept up a well-directed, but desultory fire from their positions within the caves and the stalemate continued for a few days with Chief Makoni refusing to surrender.

Harding writes that the Chief made signs that he wished to surrender on condition that his life should be spared. This request went through to the High Commissioner in Cape Town[xv] and the Chief was informed that he would have to submit to a trial and the question of life or death would depend on the result of the trial. Under these conditions, the Chief who always denied committing any murders, refused to surrender and as a result Major Watts continued his attack.

Once a supply of dynamite had arrived from Salisbury by wagon, a meeting was held to consider the best way to dislodge Chief Makoni’s people from their caves. Lieutenant Fichat and Andrew Puzey of the Umtali Volunteers with Colin Harding volunteered to run the greatest risk of placing the dynamite charges within the caves whilst under constant and heavy fire.

Lionel Cripps added: “Andrew Puzey had prepared the fuse and was let down into the cave by rope and after setting fire to the fuse was hauled up – a ticklish job and not much to his liking, so he told me.” Although the dynamite caused considerable damage to the caves, there was no surrender either of Chief Makoni or his people for the first two or three days.

Chief Makoni himself was taken prisoner on 4 September 1896 when either endeavouring to escape or else with surrender in mind he came to the cave mouth and was seized and made prisoner. The account of his capture is included in the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com and not repeated here.

Col. E.A.H. Alderson wrote: “a very brave and kindly deed was done this day by Mr Colin Harding, who was with us as volunteer and was attached to my staff. He with several others, was outside the entrance to a cave from which several family guns[xvi] had been fired. Some of the Mounted Infantry were ordered to fire volleys into the cave. Just before the order was carried out a child’s voice was heard crying inside. Mr Harding then asked leave to go in and bring it out before the volleys were fired. Should the Mashonas be still in the cave this might mean certain death to him, but in he went and came out with the little perfectly blind Mashona child in his arms…”

Execution of Chief Makoni

Major Watts hurriedly convened a field general court martial, at which Chief Makoni was found guilty of ‘armed rebellion’ and was executed by firing squad. Harding writes: “It was my unfortunate duty to be in charge of the firing party which carried this sentence into effect. Makoni died a brave man, whether he was a murderer, rebel or the devil incarnate…just before Makoni was shot and before he was tied to the grain bin, he asked me to take charge of two small children who were his sons and who stood quite close to their parent during the closing scene of his life. I did so, and as this narrative will disclose, I had no reason to regret my action.”[xvii]

Presumably Harding had been given a temporary commission as a sub-Inspector (Lieutenant) to take on the role of officer in charge of the firing party, although he does not say so.

The inquiry into the conduct of Major Watts

Harding writes: “The trial and subsequent death of Makoni was the subject of an investigation which exonerated Major Watts after he had been under open arrest for some considerable time. Whether he acted rightly or wrongly, he acted as he considered expedient and in accord with the great majority of his brother officers who were there. I leave it at that.”

Most fighting in Mashonaland had inconclusive results

As Harding writes in Frontier Patrols most of their engagements with the Mashona forces: “whether we attacked by day or night, we seldom if ever came hand to hand with the enemy, or inflicted any crushing defeat; and whereas in the earlier stages of the Rebellion they would molest a small patrol, now, incaved in their natural fortresses, they in safety hurled annoying phrases of disparagement and denunciation on their assailants and then shot them with fragments of telegraph wire, culled from the poles…”[xviii]

Appointments as Watts’ gallopers terminates, but reappointed to Lt-Col Alderson force

Grey and Harding’s appointments terminated, and they left for Salisbury accompanied by Chief Makoni’s sons and with a letter of introduction to Lt-Col Alderson. They were interviewed by Major Godley,[xix] who is describes as: “one of the most kind and cheery men it has ever been my lot to meet.” Godley persuaded both men not to join the Rhodesia Horse and they were attached to Alderson’s staff as gallopers.

Alderson commanded a force of some 2,200 men comprised of 96 Officers, 1,461 NCO’s and soldiers and 663 local native forces.

Norton family killings at Portas farm

Colin Harding writes: “Between 17 June and 18 July in Mashonaland 118 men, women and children were murdered or missing and never since been heard of.[xx]

The patrol which I accompanied left Salisbury on 17 September, Captain Pilson of the mounted infantry being in charge. The scene at Norton’s [Porta] farm which met my eyes as I arrived there, I shall never forget. Many of the dwelling rooms were still in existence, some however had been burned. Inside these rooms, underclothing, sheets, hats, stockings and odd pairs of lady’s boots were strewn about the floor. Wearing apparel suitable for men had been taken away as loot by the native murderers. Outside one ran against odds and ends of furniture and broken farm implements. The garden was desolation personified and just beyond the garden I came to three or four mounds which had been disturbed by jackals. Here I saw a lady’s shod foot protruding above the ground, close-by I discovered a heap of tumbled clothes. I can describe it in no other words. On examination it revealed the remains of another lady, but that was not all, for a diminutive form was huddled in close proximity to its murdered mother.

That evening, when all was still save the crack of an occasional rifle, assisted by one of the mounted infantry, I exhumed the bodies of my murdered friends and placed them in improvised coffins which I and my fellow soldier had made. The burial service was read over all that remained of this murdered family, and I doubt whether the virgin soil of Rhodesia rests over the earthly remains of three British subjects who can more certainly look forward to everlasting life than those whom as a solemn duty I committed to God’s own keeping.

In the midst of this pathetic and ever to be remembered eventide scene, a rustle was heard in the adjacent bush. Immediately fearing armed natives, the mounted infantry man seized his rifle and stood at the ready. It was unnecessary, for the noise we heard had been made by two emaciated hounds who now emerged, tottering in their gate from want of food. Faithful beasts that they were, they had kept guard at their homes over the remains of their mistresses, constantly, since the murders were committed and only out of fear had taken to the bush until they were satisfied that we were friendly disposed. Poor starving beasts, we took them back with us to where Captain Pilson was laagered, but although fed with condensed milk, they did not long survive their murdered owners.[xxi]

Mashonaland patrols and skirmishes

Although Grey and myself had been attached to Alderson as gallopers, it must not be supposed that we were constantly tied to his stirrup leather, quite the reverse. We were always at hand ready if required, but often we were not required, and then we got off on some patrol or other, rather like freelancers.

In one of these small patrols which was under the command of Major Tennant, Grey and I thoroughly enjoyed ourselves, ‘til Colonel Alderson arrived on the scene, then I had a bit of his tongue, but it was of the kindly sort, afterwards he said that I did not appear to pay any more attention to the Mashona bullets than if they were snowballs.

Lt-Col Alderson wrote: “Gradually Tennant worked his men up to the kraal and presently they rushed the last wall and were on top of the rock underneath which were the few remaining defenders. Now began a fight very much like that between people on the roof of a house and those inside, the one firing up the chimney, the other down; jumpy work as neither could tell when the other was going to fire. In this fighting Mr Colin Harding, who had just come up to Salisbury and who is now an Inspector in the British South Africa Company’s Police, particularly distinguished himself and paid no more attention to the Mashona bullets than if they were snowballs.”[xxii]

This above action was fought at Simbanoota’s kraal about 20 kms south of Salisbury from 8 - 14 September 1896 with Major Tennant in command of detachments of the Mounted Infantry and West Riding Regiment, the Volunteer Artillery with a seven-pounder and Maxim and the dismounted troop of the Rhodesia Horse, about 200 men. The kraal was strongly fortified, but after being shelled was rushed and burnt. The Mashona retreated into their caves which were dynamited. There were several wounded casualties (Lieut. Percival Coode, Cpl James Edward Creswick, LCpl Edward Franklin) and one trooper, Edward Johnson, was killed.

Three months later Harding was sent back to Simbanoota’s kraal with ten white and 15 native police and a Mr Mackenzie whose cattle had been stolen and traced to the kraal. The defenders fired back on the advancing patrol, Mackenzie was wounded in the hand and after burning down huts the patrol retreated to the main road.

One day, however, we both nearly got it in the neck. We had taken a kraal after some severe fighting and thinking most of the show was over, paraded the deserted village munching a well-earned, but badly baked cookie. In front of a cave, I saw a bunch of assegais. The cave was not wide or apparently deep. The assegais were well made and thinking how well they would look in my English home, I set about to secure them. Grey this time was my saviour. It was he who suggested that there might be a Mashona in the cave and that the assegais were put there as a decoy, so instead of walking straight up to the cave and certain death, I went round on the top and bending over preceded to grab the assegais. In doing so I happened to look in the cave, and there to my horror, I saw the muzzle of a Mashona gun not more than a yard away. I bobbed back my head and at the same time the man behind the gun pulled the trigger. I returned to Grey with a face black with powder, but otherwise uninjured. I was not defeated. Two sticks of dynamite put in the cave above enabled me, after the explosion, to secure the assegais and they, with the Makoni relics, are still in my hall.

Another patrol which I will remember was one under the command of Captain Sir Horace McMahon to the Mazoe Valley from 18 – 30 September 1896. The idea of it was, if possible, to arrive at a peaceful understanding with the most important insurgent Chief named Chidamba, but if he refused our peaceful overtures, to fight him. The strength of the patrol was about 200 men, a seven-pounder and Maxim gun. We arrived at our destination which was about 30 miles from our headquarters on a bright September evening and proceeded to laager at a safe distance from Chidamba's village.

The next day McMahon and Fairbairn, the District Commissioner, with three of the native contingent preceded to contact the Chief. This was rather tricky work, neither party was anxious to come too close and finally terms of surrender were discussed across a small stream. Aimless talk went on for a day or two and might have gone on ‘till this day, had not three at the rebels taken the law into their own hands and with their rifles at the trail stalked McMahon from the rear. They would undoubtedly have bagged this gallant soldier but for the quick eyes of a Mashona native policeman. This policeman, knowing the ways of his own countrymen better than we did, was on the lookout for treachery, and spotted them in time, gave the alarm and to cut matters short, negotiations were broken off.

Fairbairn continued the negotiations during which a native named Mhasvi arrived with a rifle and told Fairbairn that he was formerly one of the Chartered Company’s Native Police who had deserted at the start of the rebellion and was suspected of murdering the Native Commissioner of Mazoe district [This was Henry Hawken Pollard killed about 14 June by his Native Police at Tamaringa’s kraal; the spirit medium Charwe Nyakasikana Nehanda was charged and convicted by hanging in March 1898] A detailed account of Mhasvi is included in the article The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

McMahon wrote: “The Salisbury Rifles on the right, with Harding and Ashe, both most valuable officers, whose coolness and daring on every occasion it would be hard to beat, came in for most of the fighting and drove the enemy back from one position to the other until a determined stand was made at Chidamba’s kraal.”[xxiii]

Spirit Medium Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana or Mbuya Nehanda

In Chidamba's village lived Charwe Nyakasikana, who was considered to be the female incarnation of the oracle spirit Nehanda. Harding confirms that Nehanda’s cave was at Chidamba’s village, but all they found was a lot of property looted from the victims of the killings. To demonstrate to local people that her power was broken McMahon decided the cave should be destroyed.

Harding writes: “in an unguarded moment, I informed McMahon that I knew all about dynamite (I was not over-rating my knowledge for I had been nearly blown up on more than one occasion) consequently I was deputed to superintend the blasting of Nyamba’s [Nehanda’s] cave…

I had taken a great fancy to left Lieut Ashe,[xxiv] so I suggested to him that he should help. He did not know so much about dynamite as I did, or he would not have accepted my invitation so readily. Anyhow, we collaborated and after clearing everyone out of the vicinity of the cave (a clearance which was not difficult to effect as soon as its reason was apparent) we inserted two or three cases as far as possible into the cave. Taking every precaution, I prepared the dynamite for explosion and then deputed Ashe to put it in the cave. We had a beautiful explosion, stones, rocks, clothing, pots and every portable and conceivable thing one could imagine went flying into the air.

But the greatest joy of all was to see a human form…and thinking it was Nehanda whose witchcraft had done so much harm, I was not in the least perturbed when I heard the body pitch with a thud in the bushes near where I stood. Intending to send up a fatigue party to bury it, I with others proceeded leisurely towards our camp. We hadn't gone far when looking back, we saw a nude form approaching, apparently blind, covered in dirt and blood.

It was indeed the form which I had seen in mid-air, but unfortunately not the body of the arrogant witch doctor, but that of one of our own men who had somehow got mixed up with the explosion. It turned out afterwards that he found a £5 bank note and was diligently seeking for more, quite innocent of danger. He had been thrown out of the cave and fell through a tree, which no doubt saved his life, a distance of 30 feet. [This was Trooper Frederick Warren Day, of the Dismounted Troop, Rhodesia Horse on 28 September 1896[xxv]]

Attack on Mashayamombe’s kraal

The detailed article on Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery is under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Once again Colin Harding and Robin Grey were used as gallopers for these actions at the kraals of Chief Mashayamombe, Chena and Zimba on the Umfuli, now Mupfure river east of Hartley Hills which took place from 5 to 24 October 1896 with a large contingent of Mounted Infantry and West Riding Regiment, Salisbury Horse and Rifles supported by seven-pounder and Maxim guns. Alderson’s force comprised 350 men and they were later joined by Major Jenner’s column with 170 men and 1,000 Victoria natives.

It was during this attack that Lieut R.F. Ashe lost his arm. Harding writes: “the great risk to the people who used the dynamite was that unless it was placed right inside its value was negligible. To do this, one had to go right up to the mouth of the cave, when you would be a sure mark for any hidden armed native inside, whom you could not see or locate. Lieut Ashe, whose valour and pertinacity has been referred to, had numerous narrow escapes of being shot in this way, and finally his arm was blown off and, candidly, he was lucky that it was not his head, for the man who fired the gun was not more than three yards away from Ashe when the gun was discharged.”[xxvi]

Harding notes: “poor young Coryndon, a brother of the late Sir Robert Coryndon, was amongst the many who were killed. Coryndon met his death through one of these native traps set in front of a cave.[xxvii]

Promoted to sub-Inspector (Lieutenant) in the British South Africa Police

Lt-Col Alderson left Salisbury for Beira on 11 December 1896 with the Mounted Infantry on the arrival of Captain the Hon. F.W. de Moleyns who arrived to command the Mashonaland Mounted Police, from December 1896 to be the British South Africa Police, with the rank of Lt-Col. On the recommendation of Alderson, Harding was promoted to sub-Inspector.

BSAP Numbers at December 1896 | ||

Undrilled Police | 200 | |

Mounted Infantry * | 50 | |

Police volunteers | 400 | |

Native Police | 130 | |

780 | ||

* transferred from Lt-Col Alderson's force | ||

| ||

Colin Harding writes most were for garrison duty: only about 200 were fit for patrolling.

Patrol to Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraal

Rhodes was now meeting with the amaNdebele Indunas at the eastern Matobo and Earl Grey, the Administrator of Southern Rhodesia, was keen for peace talks to begin in Mashonaland, so Harding was despatched with Father Biehler from Chishawasha Mission and Hubert Howard, Grey’s secretary; a small party of 10 – 15 men.

The parties each waited for the other to make the first move until finally the above three walked until they were within a few hundred metres of the kraal. It was difficult getting anyone to come down and talk, but finally Chief Chikwakwa’s messengers came reluctantly down the hill. Harding told them if they surrendered their arms and handed over any individuals suspected of murder, the fighting would stop.

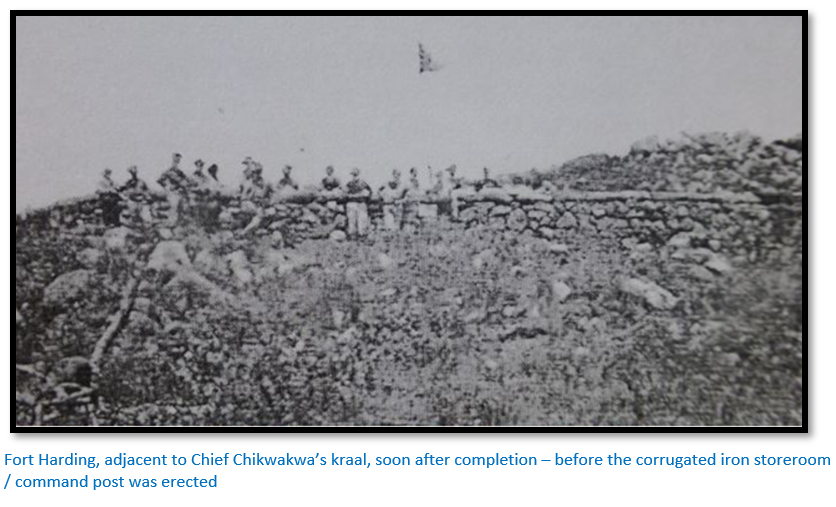

After hours of talk the messengers finally agreed to inform the Chief, after which they would send messengers to Salisbury. Further talks continued with Native Commissioner Campbell, but Chief Chikwakwa remained defiant and Major Jenner was sent with a strong force. After further fruitless talks, the force moved on to Kunzwe’s kraal who declared he wanted peace and volunteered some of his men to help build Fort Harding.

See the article Fort Harding, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm Police Camp under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

In his book Harding does not mention that the fort was named after him.[xxviii]

Inspector Roach carried out a period of repeated and futile shelling from Fort Harding of the kopje in which Chief Chikwakwa and his followers were holed up before the hill was stormed and taken and the caves blown up.

Accompanies Brevet-Major Godley to Sinoia and the Ayrshire Mine

Once again Harding with Wilson and Fox acted as gallopers to the force of 306 men with a seven-pounder and two Maxim guns, Captain Brabant in charge of the native detachment. Many of the men were almost barefoot as boots were in short supply; Godley says some were wearing “lawn-tennis shoes” and any sick going back to Salisbury left their boots! Mealies were also short for the mules and horses.

“On the 26th we came upon the first traces of the murders in the Lomagundi district. Our midday outspan was near the Sange River, and there we found two skulls, some bones, and some partly burnt letters from Jameson,[xxix] the Mining Commissioner of the district, who was supposed to have been murdered.”

Harding and Southey with another party went to the Mining Commissioner’s camp and collected all his papers and effects.[xxx]

Patrol to Chief Gurupila at Mutoko in March 1897

Sub-Inspector Harding accompanied by W.L. Armstrong, the Native Commissioner for the district and 50 Police with a Maxim gun left Salisbury and were sniped at only 10 miles from town. After four days trekking, they reached Gurupila’s kraal where Armstrong persuaded the Chief and 500 of his followers to join forces.

The undisciplined friendlies were slow to start and at one point refused to go further until supplied with Harris’ best gunpowder in one-pound tins. In addition, nobody had any experience of using the Maxim gun, except a Trooper named Lucas and Harding. Lucas, when asked however, said he did not know much about Maxims, but he had driven a mowing machine! Harding says he taught Lewis how to mount it on its tripod and arrange the ammunition belts into the breechblock, but always himself stayed close to the Maxim.

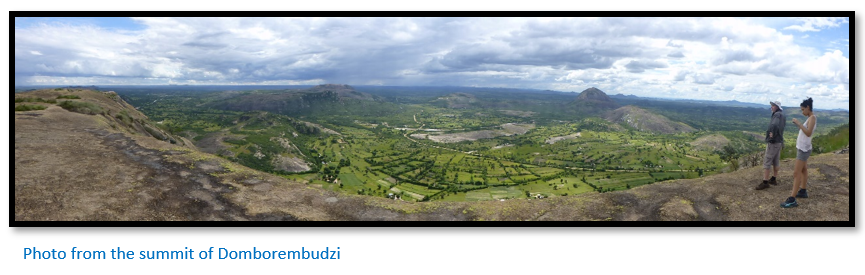

Attack on Domborembudzi, promoted to Inspector (Captain)

When they reached Domborembudzi (mountain of goats) east of the Nyagui river they were faced by a large Mashona opposition on the mountain. The column deployed into an extended line, Harding in the middle with Lucas and the Maxim gun, Howard with the police and Armstrong with Gurupila’s men. Halfway up the mountain, they were forced onto the only footpath and here a sudden fire opened up on them.

The Maxim was brought into action, a belt of ammunition quietened down the opposition, and the force continued up with considerable firing on the flanks. The Maxim came into action again but jammed after ten rounds with a broken cartridge in the breechblock. However, the native carriers with the toolbox and spare ammunition were nowhere to be found…the now useless maxim was left behind with Lucas and Howard and Harding with the police drove the defenders off the mountain summit.

Armstrong arrived after a long delay, but Gurupila’s friendlies had nearly shot him with their indiscriminate firing and then disappeared although the Chief and his headmen had stuck with him. Supplies were short, most of the police were down with fever leaving just twenty fit for action, so they made camp and at nightfall Howard volunteered to ride to Salisbury about 70 kms (43 miles) away.[xxxi]

Attack on Shaungwe’s kraal and death of Chief Gurupila

Col. de Moleyns soon arrived with reinforcements and supplies and the decision was made to attack Shaungwe’s kraal on the summit of Shaungwe hill. Harding says he was more worried by their allies than the enemy. The friendlies loaded their muskets with the same quantity of Harris’ gunpowder as their own home made gunpowder. Dried bark was used a wadding and bits of iron or small stones as bullets as lead was in short supply. Many were hurled backwards by the resultant recoil of their “family gun;” others suffered a bruised shoulder and sometimes the barrel burst.

Although the kraal was captured, Chief Gurupila was mortally wounded through the lung and died within a few hours. The Chief knew he was dying and told his followers that his time had come, and he was going to join his ancestors. His tribesmen left taking the body home for burial. Chief Shaungwe had hidden in nearby caves and the Police watched over them for some days until the chief and his followers came out and surrendered.

Harding is hospitalised with fever, promoted to Chief Inspector (Major) and given command of the Native Police

Immediately on his return to Salisbury Harding was put into hospital with malaria. Col. de Moleyns visited him and asked him to take over command of the native Police who needed to be better organised, armed, clothed and housed. One of his police colleagues who had been promoted at the same time as Harding was Lieutenant John Norton-Griffiths[xxxii] who went onto have a very distinguished career. See the article First Baronet Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths, KCB, DSO – the Great War engineer whose mine explosions at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917 were heard 240 kms away in London under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Another was Alfred Arkell Hardwick who was under Harding’s command at Fort Harding at Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal and afterwards went hunting in East Africa. His book An Ivory Trader in North Kenya: the Record of an Expedition through Kikuyu to Galla-Land in East Equatorial Africa has a dedication to Harding as follows: “To Colonel Colin Harding, C.M.G. of the British South Africa Police, to whose kind encouragement when in charge of Fort Chiquaqua, Mashonaland, the author owes his later efforts to gain colonial experience, this work is dedicated.”[xxxiii] For more details on Hardwick see the article Traveller’s tales from the Devil’s Pass under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

After an inspection by Sir Alfred Milner, the new High Commissioner for Southern Africa, the parade was complimented and thereafter recognised as a permanent force. Shortly afterwards Rhodes was also given a parade at which he was delighted and at lunch discussed the possibility of increasing the native police and decreasing the white police who were much more expensive.

Attack on Mashonganyika’s kraal in June 1897

Col. de Moleyns was down with fever, so Chief Inspector A.V. Gosling took command with 150 white police and 100 native police supported by three seven-pounders and two Maxim guns. The kraal was taken on 6 June 1897.

Attack on Kunze’s kraal and Chief Makoni’s son, Paris, mortally wounded

A dawn attack was planned on the kraal which was well-defended with a high stockade on a steep hill. A force under Gosling took part with 250 police (150 white / 100 native) supported by three seven-pounders and two Maxims. The plan was for the seven-pounders to open the stockade which would then be stormed by the native police with the white police supporting each flank.

However, the seven-pounders did not break open the stockade and the white police who should have been on either flank of the native police were wrongly positioned and began firing over the native police. Harding’s servant, Paris, one of the two sons of Makoni in the native police was mortally wounded by white police fire from the rear. When Kunze’s men returned fire, the native police went forward and reached the stockade which was at least ten feet high. No entrance could be found, but Harding and his Sergeant manage to force their way in and hold Kunze’s men at bay. The Sergeant was wounded, Harding received a nick, but fortunately support arrived and the kraal was gradually cleared.

Attack on Cheshumba’s kraal and Harding takes Chief Maramombo prisoner

The chief at this kraal had indicated previously that he wished to surrender, but afterwards strengthened his stockade, filled the grain bins in the caves and increased his fighting men. His belligerent attitude could only have one answer and on 6 July a patrol of 250 police led by de Moleyns with Captain Roach and Harding left Salisbury with two seven-pounders and two Maxim guns.

The kraal was rushed at dawn and many shot down before they managed to escape into the caves. At noon messages were sent to the chief saying he would be spared if he surrendered, but shots were fired at the messenger. The caves were well-supplied with food and water, but dynamite explosions forced the women and children to reluctantly leave their shelter. Then the men surrendered, but not Chief Maramombo.

One night whilst on duty Harding saw a Mashona trying to escape from the cave and when he failed to stop after a challenge was wounded by Harding on the arm. The doctor advised amputation, but the Chief refused and eventually it healed.

BSAP nominal roll of Officers on 30 September 1897

Mashonaland | Matabeleland | |

Commandant | Hon. FRWE de Moleyns | JS Nicholson |

Chief Inspector | AV Gosling | W. Bodle |

Inspectors & | RF Ashe | FL Bowden |

sub-Inspectors | EE Ellett | R Cashel |

RS Godley | APL Cazalet | |

J de Grey Birch | HP Constable | |

P Gwynne | GV Drury | |

CCF Hosken | G Ellis | |

CFL Money | AHJ Hore | |

MHG Mundell | ECH Kennard | |

J Norton Griffiths | H. Llewellyn | |

GMO Springfield | LE MacQueen | |

PG Stockley | B McCracken | |

GHP Williams | W.E. Murray | |

C. Southey | ||

WS Spain | ||

M. Straker | ||

AJ Tomlinson | ||

EA Wood | ||

Paymaster | CCL Money | CB Strutt |

Quartermaster | RS Godley | ET Llewellyn |

Harding’s time in Mashonaland comes to an end

Harding writes that he had a very stiff time of it in Mashonaland and made many dear friends, Howard, Hardwick and his fellow officers and enjoyed the confidence of Earl Grey and Col. de Moleyns.

Harding’s efforts were commended by Richard Martin, the Deputy Commissioner, Bulawayo to the High Commissioner, Cape Town as follows: “Inspector Harding has been present at almost every action throughout the operations and was promoted to the rank of Inspector for his gallant conduct on the first Mutoko patrol which was under fire for seven days out of ten. To him is due the rapid improvement in discipline and efficiency of the native contingent.”

Harding is posted to Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia

In early 1898 he received orders from Colonel Rivett Carnac to proceed to Northern Rhodesia to raise and command a native police force of 500 men and whilst on the journey received news that he had been awarded the C.M.G. for his services in the Mashonaland Rebellion.[xxxiv]

He travelled extensively by horseback and by dug-out canoe travelling up the Zambezi river to Lealui, the capital of Barotseland. In 1900 he went north from Lealui with his brother William to establish the source of the Zambezi and if there was effective Portuguese occupation in these areas and to determine if these tribes acknowledged Lewanika as their ruler. He travelled thousands of miles encountering slave caravans travelling to the east coast and very little signs of a Portuguese presence.

“Every day I am seeing traces of the slave trade. The wayside trees are simply hung with disused shackles, some to hold one, some two, three and even six slaves. Skull and bones bleached by the sun lie where the victims fell, gape with helpless grin on those who pass, a damning evidence of a horrible traffic… yesterday we met two caravans and today one, all proceeding to the Lunda country for their living merchandise. Some were carrying spare guns, some calico, others powder.”

After his return to Kazungula and promotion to Colonel in charge of the Barotse Native Police (BNP) he was very active recruiting and selecting sites for police posts. His orders were to take over command of the police detachment at Lealui and enlist 20 – 30 recruits with the help of his brother William and Sergeant F.C. Macaulay: “The first 25 recruits for the Barotse Native Police were attested at Lealui on 2 January 1900. Their terms of service were explained to them by the Ngambela, Lewanika’s prime minister. The engagement was for 12 months at 10/- a month for privates, 12/6 for corporals and 15/- for native sergeants. Each man was to be issued with a free uniform and a blanket.”

The BNP established Police posts at Fort Monze (which had been staffed by British South Africa Police) Kalomo, Mongu, Sesheke and Victoria Falls. Harding patrolled the Zambezi Valley as far as the Kafue river which he ascended before returning to Lealui overland in October 1900. A new journey took him up the Kabompo river with 15 of his newly recruited BNP Troopers and at Kasempa they stormed a slaver’s kraal.

During the rainy season of 1900-01 fever took so many officials in Barotseland there were only four left in the entire territory. His brother William Hallett Harding died of fever on 11 April 1901 and was buried at Fort Monze cemetery with five BSAP NCO’s and Troopers.

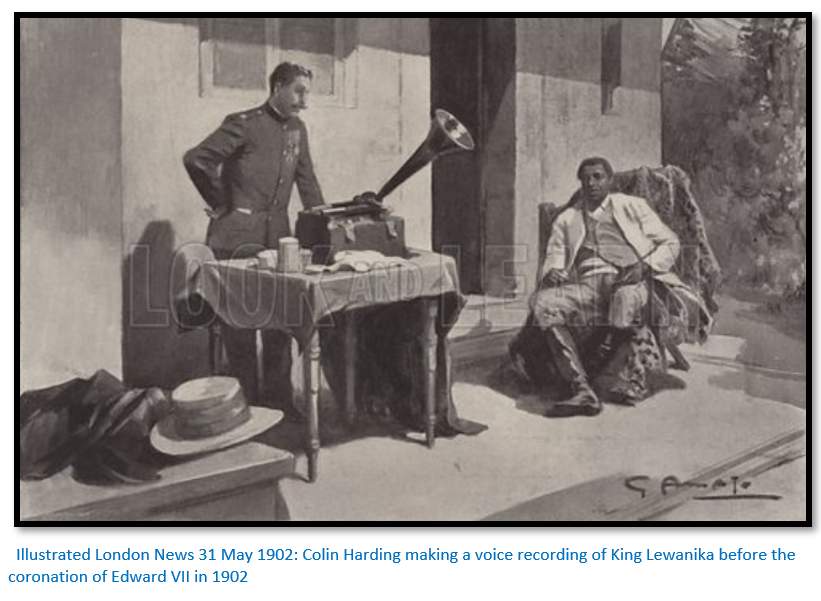

Despite these deaths by 1902 the BNP had 9 white officers and 240 African Troopers. In the same year he accompanied Lewanika, the Lozi Litunga (King) of Barotseland from 1878 to 1916 (with a break in 1884-5) for the coronation of King Edward VII. After experiencing difficulties with the BSA Company in March 1906 he resigned his commission in Barotseland. In all he says In Remotest Barotseland that he travelled on foot and by dug-out canoe nearly 13,000 kms (8,000 miles)

District Commissioner in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) from 1909 to 1914

Here he served for four years and was on leave in 1914 when war broke out.

World War 1

After assisting Jack Norton Griffiths in raising the 2nd King Edward’s Horse, Harding was in France in 1915 and from September was in command of the 15th (2nd Birmingham) Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. On 1 September 1916 the battalion was in divisional reserve when Harding was forced to handover command when he suffered from appendicitis.

Following his operation, he was considered unfit for further service and retired being awarded the DSO for his war services on 1 January 1917.

Provincial Commissioner in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) from 1917 to 1921

Here he served as a Provincial Commissioner and member of the Legislative Council until his final retirement in August 1921.

References

Lt-Col. C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall, London 1933

Lt-Col. C. Harding. In remotest Barotseland: being an account of a journey of over 8,000 miles through the wildest and remotest parts of Lewanika's Empire

Lt-Col. C. Harding. Frontier Patrols: A History of the British South Africa Police and other Rhodesian Forces. The Naval and Military Press Ltd,

The ’96 Rebellions. The British South Africa Company Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia 1896-7. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1975

Lt-Col E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo, 1971

T. Wright. Colin Harding of the 2nd Regiment, King Edward’s Horse. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research Vol. 83, No. 335 (Autumn 2005), pp. 255-257

Notes

[i] Far Bugles, P11

[ii] The cheapest accommodation on a ship

[iii] Far Bugles, P15

[iv] Ibid, P20

[v] An old fashioned apple brandy

[vi] Far Bugles, P25

[vii] Ibid, P28

[viii] Joseph Norton, his wife Caroline, baby daughter Dorothy were killed about 17 June 1896. Also killed at Porta farm were James Alexander and Harry Gravenor, farm assistants, Miss L.M. Fairweather, nurse to Mrs Norton. Those killed or reported missing in Mashonaland numbered 114.

[ix] Prior to 1895 the territory was called Zambesia, then Rhodesia and from April 1897 Southern Rhodesia

[x] Far Bugles, P30

[xi] Frontier Patrols, P88

[xii] Far Bugles, P37

[xiii] Gallopers would take messages between distant military forces

[xiv] Ibid, P41

[xv] Sir Hercules Robinson 30 May 1895 – 21 April 1897

[xvi] Family guns were usually old flintlock smooth-bore muskets loaded with locally made musket balls and black powder – often used from close-range ambush positions

[xvii] Far Bugles, P42-3

[xviii] Frontier Patrols, P97

[xix] Major Alexander Godley, rose to the rank of General and is best known for his role as commander of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and II Anzac Corps during the First World War.

[xx] The ’96 Rebellions table (P143) records 114 people murdered or missing

[xxi] Far Bugles, P49

[xxii] With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896, P161

[xxiii] Ibid, P52

[xxiv] Lieutenant Robert Fisher Ashe, Artillery Troop, Rhodesia Horse. Wounded and had his arm amputated at Mashayamombe’s kraal on 10 October 1896. Wounded again in the right thigh at Kunzwe’s kraal on 19 June 1897 (The ’96 Rebellions, P135)

[xxv] The ’96 Rebellions, P137 (accidently wounded)

[xxvi] Far Bugles, P54

[xxvii] The ’96 Rebellions, P133. Trooper John Selby Coryndon, Salisbury Rifles, killed 11 October 1896 at Chena’s kraal

[xxviii] Frontier Patrols, P102

[xxix] Arthur John Jameson. Mining Commissioner murdered at his camp at Lomagundi about the 21 June 1896

[xxx] With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896, P223

[xxxi] Far Bugles, P63

[xxxii] Jack Norton Griffiths transferred out of the Natal Troop as a sergeant

[xxxiii] Ibid, P66

[xxxiv] CMG stands for Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: