Home >

Mashonaland Central >

Vasco Fernandes Homem and the search for the Mutapa state’s fabled gold mines 1574-5

Vasco Fernandes Homem and the search for the Mutapa state’s fabled gold mines 1574-5

Sources

Much of the detailed information used here and in the article on Francisco Barreto is taken from the excellent article Between Mission and Conquest: A Review of Francisco Barreto’s Expedition to Mutapa (1569-1573) by Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos.

The reasons behind Portugal needing the Mutapa state’s gold

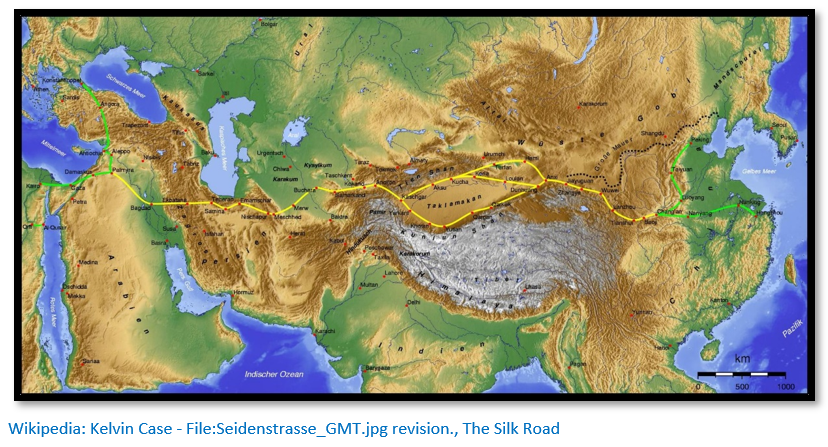

The silk road is the name given to the extensive intercontinental trade network that connected the east and west from about the 2nd Century BCE. Wikipedia states the silk road was central to the economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between east Asia and southern Europe.[i]

The silk road is in many respects a misnomer. Silk was traded, as the Wikipedia article states: “but many other goods and ideas were exchanged, including religions (especially Buddhism) syncretic philosophies, scientific discoveries, and technologies like paper and gunpowder."

Other commodities traded included jade and horses bred on the Eurasian steppes were exchanged for goods that only agricultural societies produced, such as grain, and later in the Roman period, glassware, spices, perfumes, coins, silverware and silk.

Between the 8 – 13th Centuries during the Islamic era Damascus and then Baghdad became the major trade centres along the silk road.

In the 13 – 14th Centuries the Mongols gained dominance and developed overland and maritime routes throughout the Eurasian continent, Black Sea and Mediterranean in the west and Indian Ocean in the south. The Chinese had traded in the Indian Ocean at an earlier time and in Mongol times trade flourished in the Indian Ocean.

At this time, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China and his accounts, documented in The Travels of Marco Polo, opened Western eyes to the culture and products of the Far East.

After the fall of the Mongol Empire, the great political powers along the silk road became economically and culturally separated.

The spice trade

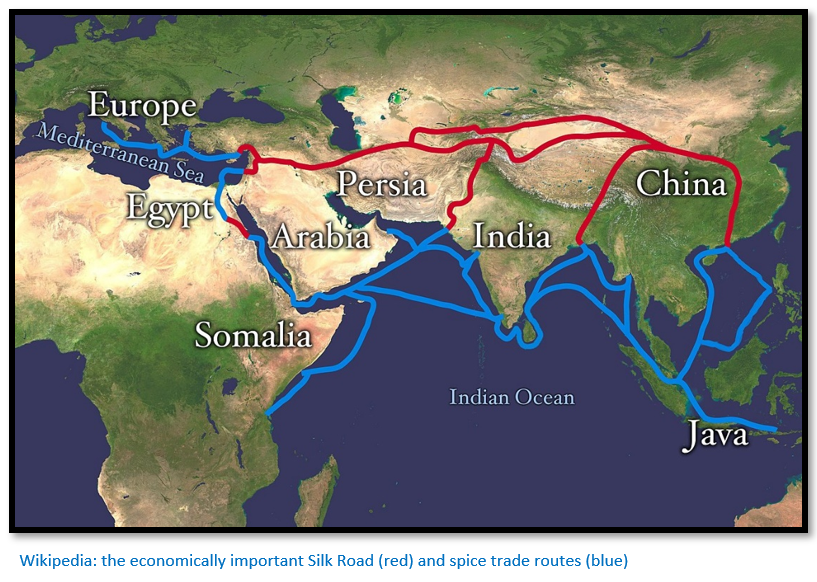

Many spices including cardamon, cassis, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, mace, nutmeg, pepper, star anise and turmeric were traded before the beginning of the Christian era. From southeast Asia and Indonesia they were transported by sea through the Malacca Straits with additional products coming from India and Sri Lanka and then shipped across the Indian Ocean and into the Red Sea by Indian and Persian traders.

During the first millennium AD the Ethiopians became the major trading power in the Red Sea, later succeeded by Jewish and Arabs traders. Their goods were then transported by land and sea towards the Mediterranean and the Grec0-Roman world by Venetian merchants and later by the Ottoman Turks.

From the 8th until the 15th century, the maritime republics (Ancona, Genoa, Pisa, Venice) and duchies (Amalfi, Gaeta and Ragusa) held a monopoly on European trade with the Middle East and acted as the middlemen for the old commodities of silk and spice plus new trade items including incense, herbs, drugs and opium – these products made the Mediterranean city-states extremely wealthy and formidable powers.

From 1453 the Ottoman Empire began to also vie for control of the spice trade route and being at the edge of Europe and Asia was in a strong position to charge hefty taxes on merchandise being transported to the west.

The Portuguese decide they want a slice of the trade

Portugal in an attempt to break the Venetian and Ottoman hold on the spice trade began to build up a maritime capacity. The western Europeans did not want to be dependent on an expansionist, non-Christian power for this rewarding trade with the East and set out to find an alternative route by sea around Africa.

Under Henry the Navigator Portugal’s captains were encouraged to find an alternative sea route around Africa with the ultimate prize of a monopoly on the trade route to the East Indies. Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and nine years later in 1497 during the reign of Manuel I, Vasco da Gama continued their exploration up the east coast of Africa as far as Malindi and then using a Swahili pilot sailed across the Indian Ocean to Calicut in south India. [For background see the article Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century? under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Portugal’s dilemma – what do they use to purchase the spices?

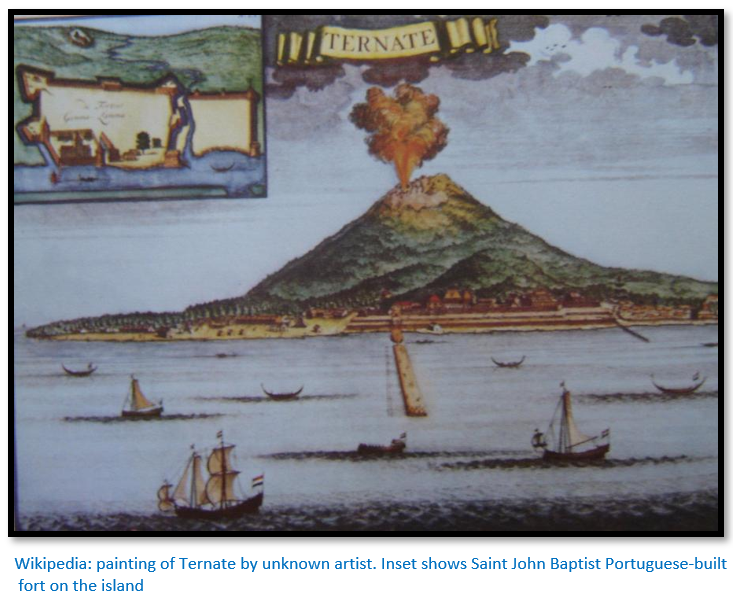

In 1511 Afonso de Albuquerque had conquered Malacca, Kerala and Sri Lanka and Portuguese galleons under Antonio de Abreu sailed in 1512 to the islands of Ambon, Buru, Seram and Ternate - the Moluccas, an archipelago in eastern Indonesia. The Portuguese now had complete control of the Africa sea route through a network of routes that extended from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean and finally the Atlantic Ocean. The wealth of the East was now open to Portugal and being the first European power, potentially the biggest profits from the spice trade were within grasping distance.

Heidi Gengenbach writes that in January 1498 when Vasco da Gama’s fleet stopped for a month at the Cuacua river[ii] near Quelimane, on their journey of discovery to India, they were surrounded by: “great groves of trees, which give much fruit of many kinds” – the men at the time had clear signs of scurvy after their long voyage from Lisbon. Da Gama’s diarist mentions local people “of good physique” bringing food by canoe to the Portuguese seafarers and allowing them to “take water” from their village.

This was not enough to feed hungry crews and the ‘haughty’ silk and satin-capped African chiefs and merchants who boarded da Gama’s ships ‘valued nothing’ the Portuguese had to offer, and the crew were not able to trade for the lemons and oranges, melons, cucumbers, sugar-cane, coconuts, poultry and goats they so desperately needed. Gengenbach suggests the Africans relished the fact that their food held power over the Portuguese and perhaps withheld it to demonstrate their power.[iii]

She quotes the inaugural exchange of gifts in 1502 between Pero Afonso de Aguiar and Sheik Yusuf, Sofala’s Muslim ruler when ‘a very fine piece of scarlet cloth and other pieces of fine coloured cloths, and a very large Flanders mirror, and knives, and red caps, and a quantity of cut-glass beads strung together’ were exchanged for ‘fowls and yams and goats and foodstuffs and things to eat that were in the land.’

Their problem is what do they have to offer in exchange for the spices? Portugal needed gold and silver bullion sources like those that Spain already had.

The Spanish colonies in Latin America have silver and gold bullion for trading

From 1545 huge quantities of silver were discovered at Potosí, in modern Bolivia. This region, high in the Andes at over 4,000 metres, is so rich in both silver and tin that it eventually had as many as 5,000 working mines and tens of thousands of slaves and indigenous people have died over the years, as a direct result of cave-ins, overwork, hunger and disease.

In 1546, a year after the discovery at Potosí, silver was found at Zacatecas in Mexico and other major new sources of silver and gold were found in Mexico in the next few years. Convoys of Spanish caravels carried European goods to Portobelo and took back to Spain the silver and gold used to pay for it, together with the 20% tax of all gold and silver due to the Spanish crown.

The Swahili coast becomes important because of the gold flowing from the interior

The Portuguese soon found that the spice traders in the East were not interested in the trade goods which they carried, they wanted silver or gold bullion in exchange. In 1505 and 1506 the Portuguese established permanent fortified bases at Sofala, south of Beira and at Mozambique Island. At Mozambique Island their ships could resupply and carry out repairs after rounding the stormy Cape, land sick crews and take on fresh ones before catching the monsoon winds across the Indian Ocean.[iv]

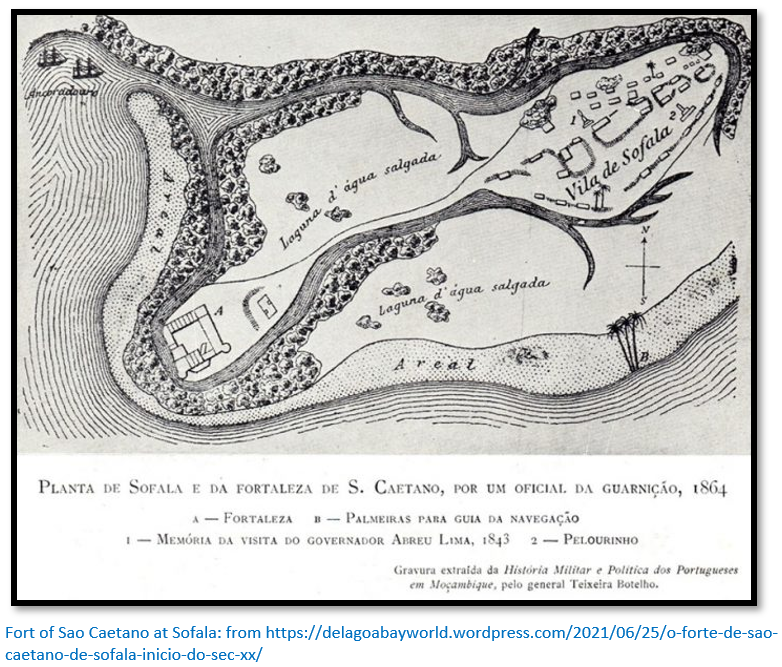

Forts were built at Kilwa and Sofala, but Kilwa was soon abandoned and Fort São Caetano at Sofala was garrisoned in hope that it would come to dominate the gold trade that was mined somewhere in the interior. The Portuguese hope was that if they managed to monopolise the gold trade with the interior it would provide them with the means to purchase spices in the East.

However the Swahili traders already dominate the gold trade on the east African coast

Initially the Portuguese attempted to monopolise the gold trade and did their best to force the traders on the coast to recognise this. Their carracks (Portuguese nau) were three or four masted ocean-going vessels with large cargo holds for long sea voyages weighing 250 – 500 tons with a crew of 40 – 80 sailors and heavily armed with pairs of bronze nine-pound demi-culverins on truck carriages.[v] The Swahili dhows were no match for the Portuguese carracks and they rapidly dominated the Indian Ocean.

However it was a different matter altogether on land. The Portuguese attempted to form alliances with the rulers of the coastal cities that would be mutually advantageous, but only Malindi was agreeable.

At Kilwa the Portuguese tried to work with the local rulers, but the relationship soon broke down. Kilwa was soon abandoned by the Portuguese and the town never regained its previous commercial dominance. At Mozambique Island a relationship was established after the Muslim population moved to the mainland and other Muslim towns that were actively hostile were attacked and ransacked; Angoche in 1513, Querimba in 1522 and Mombasa in 1524.[vi]

A warring state of affairs continued in the 1580’s when the northernmost coastal towns on the Swahili coast were supported by Turkish galleys and in the 1650’s when an Omani fleet engaged the Portuguese. Portuguese influence along the northern end of the Swahili coast ended in 1698 when Mombasa was lost to a combined local / Omani force.

The Portuguese resort to violence in some areas of the Swahili coast

Further north at Malindi in 1498 an Arab vessel was attacked and overwhelmed for its provisions, gold, and silver, in August 1505 they loot warehouses at Mombasa for their supplies of rice, honey, butter and grain and in 1506 at Madagascar they slaughter a Muslim community for their huge supplies of rice.[vii]

At Sofala and Mozambique Island the Portuguese and Muslims establish a working relationship

The Portuguese at Mozambique Island and Sofala were more pragmatic than violent as they wished to be part of the gold trading network and their relationship was cordial. Provisions were purchased from local people through local agents, and ivory being bulky unlike gold, was brought to the coastal ports from the interior and purchased by the Portuguese through local networks. In addition many individual Portuguese traders at coastal ports and on the Querimba Islands off north eastern Mozambique, close to Pemba, as well as Sena and Tete married local women and adopted lifestyles and commercial practices that fitted in with the local culture.

Many Portuguese including Antonio Fernandes, Duarte Barbosa, João Dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental and even the Jesuit Father Francisco de Monclaro describe the foodstuffs of the interior as plentiful and abundant, but they soon learned that the provisions that they needed would not be as easy as they thought to obtain. Figueroa, a Spaniard travelling with Captain Pero d’Anaia that arrived at Sofala in September 1505, wrote that Sofala had groves of coconut palms from which wine, vinegar, oil and honey were made, as well as ‘marvellous figs that turn to butter in your mouth’ sugarcane, sheep and chickens.

D’Anaia had 300 men to build a fortress, factory and church at Sofala, but as the rainy season advanced his men increasingly succumbed to malaria. Figueroa writes: “most of [the men] began to fall sick with fever and every day or so two or three would die.”[viii] D’Anaia was forced to send a party of men up the Buzi river to acquire provisions which were traded for Venetian glass beads, Brittany cloth, ‘piss pots’ and brass bangles and bells and 40 men had died of fever by November 1505. By February 1506 the remaining 150 men were living on strict rations.

By May 1506 the desperate situation encouraged Sheik Yusuf to attack the settlement and a large force led by the Swahili Muslims attacked the fortress then sheltering: “only 35 men…who could bear arms” and “the others…in such a state that it took five or six of them to draw a cross-bow.” But the settlement had been warned by a Muslim merchant friend and Portuguese artillery beat back the attackers. Sheik Yusuf was caught and killed and a more tolerant ruler put in his place. By late May d’Anaia had himself died of fever with only about 40 survivors left in desperate straits.

Without acceptable products and gold and silver bullion for trading the Sofala trade stagnated and by the 1650’s the Portuguese Captain of Sofala and Mozambique had moved his base to Mozambique Island.

Background to Homem’s expedition from Sofala; Francisco Barreto’s expedition to Sena King Sebastian of Portugal gave Francisco Barreto the job of leading an expedition to the Mutapa state (Monomotapa - present day Zimbabwe) to take over their legendary gold mines. As already stated the Portuguese desperately wished to match Spain’s discoveries with its fabulous silver mines at Potosí in Bolivia, and gold and silver mines in Peru and Mexico in order to pay for the spices of the East.

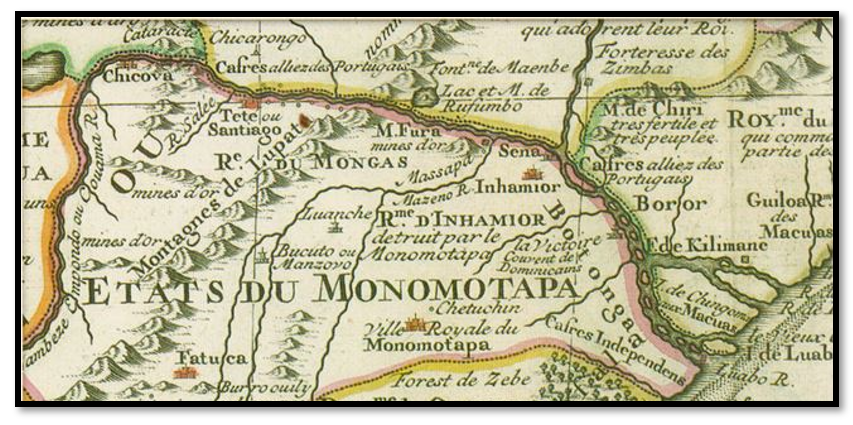

This 1727 map by Moll clearly shows the Mutapa State (Monomotapa) south of the Zambesi. The Chicova silver mines are west of Tete and Mongas territory is marked between Tete and Sena. The Mazeno (Mazowe) river is shown just west of Sena

Barreto’s fleet sailed from Lisbon on 16 April 1569, with three ships, 1,000 men, and the title of Conqueror of the Mines, bestowed upon him by the King of Portugal. The first ship arrived in Mozambique in August 1569; Barreto's on 14 March of the next year, and the third ship months later. [See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Barreto’s fatal mistake

Barreto preferred to take the shorter and easier route via Sofala to the location of the Manyika gold mines. However King Sebastian had given Barreto instructions that he was to: "undertake nothing of importance without the advice and concurrence" of the Jesuit Priest Francisco Monclaro. Monclaro was in fact the de facto second in command.

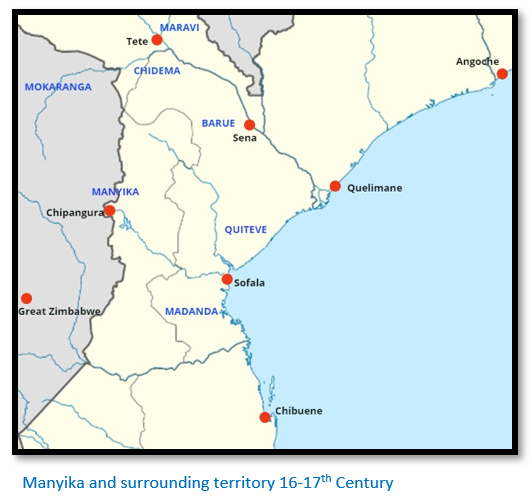

Local merchants and residents at Mozambique Island recommended the Sofala route as being shorter and less dangerous, that the Kings of Manyika and Uteve, both vassals of the Mutapa state were at war with each other and would not hinder their passage, but if they took the Zambesi route they could expect fierce opposition from the Mongas (called the Samungazi by some authors) The Mocambique Council accepted these recommendations and advised that Barreto’s military expedition take the Sofala route.

But Father Monclaro demanded that the expedition take the Sena route, rather than the Sofala route, as he believed this would lead them to where the Jesuit, Goncalo da Silveira S.J. had been thrown into the Musengezi river and martyred in 1561. Because of the King’s instructions and a threat from Monclaro that he would leave for India if the military expedition did not follow the Zambesi route, his view prevailed over Barreto’s instincts and the advice of local residents, and so the expedition set out for Chipangura (also Macequece or Massi-Kessi, now Manica) the reputed location of the gold mines, via the Sena route.

Barreto’s military expedition leaves Sena on the Zambesi river

After an abortive expedition to Zanzibar, then Mombasa, Meline and Pate which took eighteen months Barreto’s expedition sailed up the Cuama River - the Zambezi River, but the Swahili traders called one of their outposts Cuama and early explorers confused this with the name of the river - armed with weapons and mining tools and arrived at Sena on 18 December 1571 with 700 soldiers. Barreto sent an envoy to the Emperor of Monomotapa with a request for permission to attack the Mongas,[ix] whose territory lay between the Portuguese and the gold mines. The emperor granted Barreto permission to attack them and even went so far to offer his own army in support. Barreto, however, declined assistance, and marched onward upriver.

The Portuguese fought several battles against the Mongas, claiming victory in all of them despite the overwhelming numbers, due to their guns, but more probably the battle results were largely inconclusive. When the Mongas King sent ambassadors to Barreto in hopes of securing a peace, the soldier tricked him into thinking that the camels used by the Portuguese, animals unknown in south eastern Africa, subsisted on flesh, leading the Mongas to provide the Portuguese with beef for the camels.

Two of the factors which defeated Barreto’s expedition

Firstly, the Portuguese had commenced their expedition in December in the middle of the rainy season with the onset of malaria. Even before they left Sena, Barreto’s son and 80 soldiers had perished from fever. The numbers of sick grew as they proceeded up the Zambesi river and seriously weakened Barreto’s forces.

Secondly, Barreto counted on provisions and supplies being available for his men, cattle and horses from local natives along the route. But the Mongas made sure any surplus foodstuffs were hidden well away from Barreto’s men and the problem only increased as they advanced into the interior.

Before the expedition could progress further, Barreto was recalled to the Island of Mozambique to deal with António Pereira Brandão, whom Barreto had appointed as commander at Mozambique Island and was now spreading false information about Barreto. The governor removed him from duty as commander of the São Sebastião fort and returned to Sena where his men were waiting. Homem was left in charge of the military expedition, but many soldiers fell sick or died and Homem was forced to retreat to Sena. Finally Barreto re-joined the much depleted garrison at Sena, only to also fall ill and die at Sena on July 9, 1573.[x]

Homem continues the search for the goldmines of Mutapa via the Sofala route

Barreto's deputy, Vasco Fernandes Homem, succeeded him as Captain of Sofala and Governor and returned with the remaining soldiers of the military expedition to the coast. After the Jesuit Priest Monclaro had left for Lisbon and Homem was free to consult with local traders about the route to the mines, the expedition to Chipangura (now the modern day town of Manica) was resumed via the Sofala route to assess the potential of gold mining in Manyika.

Homem left Mozambique Island with 4 ships and 412 soldiers, although over 50 deserted, and arrived at Sofala in May 1574. Logistical problems delayed the military expedition from moving into the interior until December 1574. Once again they faced the same problems they encountered on Barreto’s military expedition, increasing sick from malaria fever during the rains and a lack of provisions.

Homem knew there was a war between Uteve and Manyika. To reach the goldmines he had to pass through Uteve and Homem asked the king of Uteve for provisions. The king refused unless he was given weapons by the Portuguese. Homem responded by attacking Uteve and capturing members of the royal family and burning down the capital. His soldiers were forbidden from pursuing those defeated as Homem’s plan was just to obtain provisions and continue to Manyika. For safety he followed the river [probably the Buzi and then the Revue rivers] to avoid the mistakes Barreto had made in his fight with the Mongas (Samungazi)

Arrival at Manyika (Manica) and a friendly reception from the Chikanga

On his arrival at Manyika Homem and his military expedition was well received by the Chikanga who permitted Homem to explore his mines. His chief miner was a Castilian Agostinho de Sottomaior, who confirmed the Manyika gold mines were richer than in Mexico, then called New Spain, but that they required mining equipment to be properly exploited.[xi]

A Treaty is signed between Portugal and Manyika

The Chikanga confirmed that the richest goldmines were in the lands of the Mutapa’s tributes and not in the Mutapa heartlands themselves and Homem concluded that commerce would be more profitable than further exploration or direct exploitation.

A treaty was signed promising safe access to the Portuguese to the gold fairs of Manyika (Chipangura) and encouraging peaceful trade between them.

Homem heard news of the approach of a Mutapa army and held a council to decide whether to return to Sofala. On the basis that peaceful relations had been established with Manyika and the Mutapa state ruler Chisamharu Negomo, Homem decided to resume the search for the Chicova silver mines donated by the Mutapa ruler to the Portuguese that had so thwarted the efforts of Francisco Barreto.

On his return to Sofala, he returned the captured members of the Uteve royal family but aware that Uteve had impeded his passage to Manyika, Homem forced the King of Uteve to pay tribute (the curva) to the Portuguese, reversing the previous arrangement under which the captain of Sofala had to pay Uteve to gain passage through their territory.

Extract details of the fortress itself are included in the notes written by Zarina Matsinhes at https://knoow.net/historia/historia-de-mocambique/forte-de-sofala/[xii]

Homem undertakes a new military expedition up the Cuama (Zambesi) river

Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos writes: “Homem had clearly chosen his own path, in order to present to King Sebastian different and better results than Barreto.”[xiii]

In 1575 following the arrival of fresh soldiers from Portugal Homem guided the new military expedition up the Zambesi reaching Sena on 29 November 1575, again at the onset of the deadly rainy season. From there he took 230 soldiers on to Tete where they built a fort – the remains are visible today.

From there they made for the Chicova silver mines which had so frustrated Barreto on the previous expedition. But as before, the indigenous people could or would not disclose their location – as a result Homem imprisoned the local ruler. Here he received the Mutapa’s ambassadors who confirmed the Mutapa’s gift of the mines, but their location remained a mystery.

In early 1576 King Sebastian sent a new governor, D. Fernando de Monroy to Mozambique Island. Sensing that this move meant the end of Sebastian’s support for his expedition - Homem returned to Mozambique Island. Before leaving he instructed António Cardoso de Almeida to build a fort in Chicova and to explore the region. Almeida built the fort, but once again provisions became short, and he had to resort to force to obtain them. Local people promised to led Almeida to the silver mines, but in fact it was an ambush, and his men were slaughtered effectively bringing Portuguese efforts to find the mines to an end.

Despite all these setbacks Homem still believed that the Chicova mines might be commercially valuable. However unlike most of the Portuguese soldiers of the two military expeditions that attempted to reach the Mutapa state, Vasco Fernandes Homem did return to Portugal and probably met with King Sebastian. But by now the King’s enthusiasm for the gold mines of the Mutapa state had reached its end. The wily tactics of Chisamharu Negomo ensured that the Portuguese military expeditions never reached their intended objectives.

The smart tactics of Chisamharu Negomo, ruler of the Mutapa state

Following the killing of the Jesuit Father Goncalo da Silveira S.J. at the hands of his court officials Negomo was warned by several Portuguese that he had ordered the death of an envoy from the viceroy of India, Silveira himself came from a noble family and that he should expect a Portuguese military expedition in retaliation. [See the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Regretting his previous actions, Negomo ordered the killing of the four Swahili Muslims who had provoked Silveira’s death. Two years of plague followed, which Negomo interpreted as God’s displeasure, he had his mother killed and sent his ambassador to the captain at Sofala. When news of Barreto’s military expedition came, he was not surprised as he had been warned it would happen.[xiv]

Once Negomo realised that the expedition had a twofold aim; to recover Silveira’s body and to find the source of the gold reaching Sofala, his main aim was to prevent Barreto and Homem from reaching the Mutapa state itself. By approving Barreto’s fight against the Mongas, but also implying through his ambassadors that he could reinforce Barreto with an army of 100,000 soldiers, he cast doubt in Portuguese minds whether they could invade the northern Mashonaland plateau at the heart of the Mutapa state. Donating the Chikova silver mines to the Portuguese was a simple decoy to distract them…it is doubtful they ever existed.

At all times Negomo kept himself well informed of both Barreto and Homem’s movements and always managed to delay the threat that they represented through his ambassadors by threatening to intervene with his own army if necessary. His success in keeping the Portuguese at bay contrasts sharply with his successor Gatsi Rusere’s policy of actually requesting assistance from the Portuguese in his internal succession struggles.

Discussion on why the Barreto / Homem military expeditions to the Mutapa state failed

(1) Clearly the prevalence of tsetse-fly and malaria were major factors that quickly weakened the Portuguese forces. It is surprising that not more attention was paid to local traders and residents advice – they would be well aware that the onset of the rainy seasons meant fever became a big problem.

(2) Mudenge argues that the poor advice of Father Monclaro insisting on Barreto’s expedition taking the route via Sena played a major part in his failure to reach the Mutapa state and the waste of resources through the diversionary battles with the Mongas (Samungazi)

(3) Malyn Hewitt believes the combination the expedition was too large with a cumbersome baggage train, disease, lack of knowledge on local conditions and geography and multiple enemy forces

(4) Elkiss blames the delays at the start of the expedition, Barreto’s lack of leadership, disease and the negative influence of Father Monclaro

(5) Schebesta emphasised the conflict between the political and religious aims of the expedition and their incompatibility.

Clearly the military expeditions of Barreto and Homem marked the first time the Portuguese embarked in strength into the interior. Traders and explorers such as Antonio Fernandes, the degredado sent from Sofala had penetrated the interior previously, but their impact was very limited. [See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The military expeditions had absorbed a great deal of resources and manpower and cost many lives. Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos writes: “the expedition came be to re-membered as a traumatic event not only by the men who had participated in it but also by the Crown.”[xv]

The gold fair at Chipangura, Manyika

Chipangura was the pre-Portuguese capital of the Manyika Kingdom and the site of a gold fair; the centre of the gold trade with the Swahili merchants, and the major objective of Barreto’s failed expedition in 1570. Vasco Homem reached Chipangura in 1575 and as the town is only 30 kilometres east of Penhalonga, obtained permission to visit the mines there.

The mines of Manyika, when finally reached, did not bear any resemble to the legends, as the gold required extraction from the ore through panning and the labour requirements were enormous, with the natives only producing very small amounts of gold during the dry season when the water table fell, and river levels were low. Most mining was done once planting was complete with agriculture predominating. After concluding the peace treaty with Manyika, Homem abandoned the search for gold. His report to the King was not encouraging, as he believed extracting gold required machinery and trained miners and in 1577 he was replaced.

Portuguese contacts with the Manyika ruler improve and trading revives at Chipangura

However, Homem’s contacts with Chipangura resulted in good trade relations with the Chicanga rulers and Portuguese traders or their followers, the vashambadzi, who began to regularly visit the gold fair. In the 1630's there were some 50 Portuguese traders at Chipangura with a Portuguese captain and a resident priest. Subsidiary trading settlements were at Matuca and at the Bvumba. Portuguese dominance continued until the Rozvi Changamire crossed from modern day Zimbabwe in 1695 and destroyed the town.

By 1720 a new trade fair had been established at Chipangura, now called Macequece (or Massi-Kessi) under the joint rule of a traditional Chicanga ruler and a Portuguese captain. Actual gold mining remained a Chicanga monopoly, but ivory, gemstones, copper, iron and cattle were also traded although gradually the trade fell off and by 1835 Macequece was abandoned.

In the 1850's the Portuguese tried to re-establish the gold fair, but by then ivory was a more important trade item. Macequece was renamed Manica by the Portuguese who tried to revive the gold trade and built a fort on the site in 1890 due to tension with the British South Africa Company over the territorial boundaries with Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

References

P. Briggs. Mozambique. Bradt Travel Guides

F.C. Danvers. The Portuguese in India. Volume 1: 1481 – 1571. Asian Educational Services 1992

H. Gengenbach. Provisions and Power on an Imperial Frontier: A gendered history of hunger in 16th Century Central Mozambique. The International Journal of African Historical Studies

Vol. 50, No. 3 (2017), pp. 409-437 (29 pages)

M.Newitt. A Short History of Mozambique. C. Hurst and Co. London 1995

Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos. Between Mission and Conquest: A Review of Francisco Barreto’s Expedition to Mutapa (1569-1573) Vila-Santa, Portuguese Studies Review 24 (1) (2016) 51-90

J. Vaucher. April 2019. Ships of Discovery. https://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~vaucher/History/Ships/Ships_Discovery/index.html#carrack

Wikipedia

Notes

[i] Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road

[ii] Or the Quelimane river, named by da Gama as Rio dos Bon Sinai (river of Good Signs)

[iii] Provisions and Power on an Imperial Frontier, P417

[iv] A Short History of Mozambique. P24

[v] Ships of Discovery. Exploration of a sunken Nao, the Nossa Senhora dos Mártires has provided much information about these ships. "In 1606, after 9 month at sea returning from India, the Nossa sank in view of Lisbon. She was a Nao with a 40 m hull and 9 m beam. The cargo, the main reason for the voyage, consisted of 250 tons of peppercorns, complemented with many other spices and drugs, countless bales of cotton and silk cloth of all sizes and colours, furniture, porcelain, exotic animals and thousands of luxury items from the workshops of the far east. The ship also carried 450 people, including crew and passengers, food and water for six months, spares and fittings."

[vi] A Short History of Mozambique. P26

[vii] Provisions and Power on an Imperial Frontier, P418

[viii] Ibid, P421

[ix] Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa Braga Campos refers to the Mongas as the Samungazi

[x] Ibid: his body was taken back to Portugal in 1574 and buried with full military honours

[xi] Ibid, P79

[xii] The fort had a square plan, with walls 22 meters long, and bastions with a circular plan at the vertices. On the side facing the sea rose the keep that communicated with the residence of the captain of the fort. In the span of said tower there was a large cistern that supplied water to all the garrison installed there. On the land side, the buildings destined for the factory were built. The village was dispersed outside the walls of the fort.

The responsibility for building the fort was assigned to Pêro de Anaia, who on 18 May 1505 left Lisbon with six ships specifically for that purpose. Arriving in Sofala, Anaia makes some agreements with a local chief and starts building the fort on September 25, 1505. The site chosen for its construction was a small, low, sandy promontory, close to the bar and accessible to the anchorage. Initially built in wood, it was replaced from 1507 onwards by stone structures (including the walls and the main tower), which were safer and more resistant. Given the scarcity of materials in the region, it was necessary to bring them from more distant places and even from the metropolis.

In 1900 part of the wall collapsed and in 1903 it was the turn of the keep to partially collapse, coming to collapse completely shortly afterwards. In 1905, after the collapse of the tower, the Secretary of State for Naval and Overseas Affairs authorized the handover of the fortress to the Companhia de Moçambique, with the proviso that it be preserved as a historical monument. However, and given the high costs, the fort would never be recovered, with a large part of the stones used in its construction taken to the city of Beira and to other cities for the construction of buildings. Currently, what little remains of the fort is submerged, partly visible during low tide.

[xiii] Between Mission and Conquest, P81

[xiv] Ibid, P84

[xv] Ibid, P89

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: