Home >

Mashonaland Central >

The Kirby family and their Salvation Army connection in early Rhodesia with the Pearson Settlement Farm from 1920 and the Howard Institute from 1923 (Part 1 of 2)

The Kirby family and their Salvation Army connection in early Rhodesia with the Pearson Settlement Farm from 1920 and the Howard Institute from 1923 (Part 1 of 2)

Leonard Andrew Kirby, the father of the author of this article is referred to as “Dad,” Leonard Field Kirby, the author is “I, or the author.” Rose Emma Field is “Mum” and “Rose” is their daughter and “Andrew” is the youngest son.

Part 2 of 2 is under Matabeleland South.

Background on early Missionary work in Matabeleland and Mashonaland

The Army arrived later than most of the other missionary societies. Thanks to a special friendship that grew between Robert Moffat at Kuruman and Mzilikazi, the London Missionary Society (LMS) were given permission to establish a mission station at Inyati[i] (present-day Inyathi) on 26 December 1859. In 1870 Mzilikazi’s son, Lobengula, granted the LMS land for a second mission station at Hope Fountain.[ii]

The Roman Catholics arrived twenty years later in 1879 under Father Depelchin, and after a wait of some months, were given permission to buy Greite’s house and land from the English trader Grant to establish the Jesuit Mission[iii] near Lobengula’s capital at Old Bulawayo. Mother Patrick’s Dominican sisters arrived at Fort Salisbury in July 1891, four months before the Salvation Army, to establish a hospital, and by the next year had also established a convent chapel and school. The same year the Jesuits established a mission at Chishawasha near Salisbury.[iv]

The Church of England (Anglican) missionaries were the last to arrive before the 1890 Pioneer column, in 1888 Bishop Knight-Bruce had long negotiations with King Lobengula who was not keen to have more missionaries in Matabeleland.

Within a year of the Mashonaland occupation, the Dutch Reformed Church set up a mission at Morgenster, near Great Zimbabwe, and the British Methodists were established at Fort Salisbury.

The Salvation Army comes to Mashonaland in 1891

On 5 May 1891 the Army’s ox-wagon named “Enterprise” left Kimberley on a 950 mile (1,370 km) trek that lasted six months arriving on 18 November 1891 at Fort Salisbury. The party’s leader was Major John Pascoe with his wife and two daughters, the first white children to arrive in Salisbury, accompanied by Captains Edward Cass, David Crook, Edgar Mahon, Bob Scott and Theodore Searle.[v]

Norman Murdoch writes that the Salvation Army came to Mashonaland with a plan to evangelize whites and then to find land in pursuit of General Booth’s plan for England’s urban unemployed to be re-settled, but they soon realized that they was not succeeding in either goal and the ‘Army’s’ ultimate success came from a desire that it had only vaguely considered in 1891—to convert Africans to Christianity.[vi]

Murdoch’s view is confirmed by W.D. ‘Bill’ Gale who used many early pioneer reminiscences as source material and writes[vii] that Canon Balfour built the first church, but his retiring nature had little in common with the mixed crowd of miners, traders and speculators who formed the majority of the population. He was followed by the Jesuits in the form of Father Hartman, who quickly won the respect of everybody, and was followed by the Wesleyans.

Gale states the arrival in November 1891 of the Salvation Army at Salisbury caused the greatest stir. The party in their red jerseys arrived in their wagons and announced their presence the following Saturday in typical ‘Army’ fashion by playing their band instruments outside the bars of Pioneer Street. This quickly drew a large mixed crowd of men, for many natives this was the first brass band they had ever heard and was followed up by a stirring address from Major Pascoe. The following evening Mrs Pascoe, who had an excellent voice, sang a hymn to the tune of ‘Robin Adair’ at an Army service held at the kopje that was well-attended. The children, Mrs Pascoe’s voice and the brass band initially all made a big impression, but they soon learned that there was no great appetite for their services amongst the white settlers and gradually concentrated their efforts on the natives.

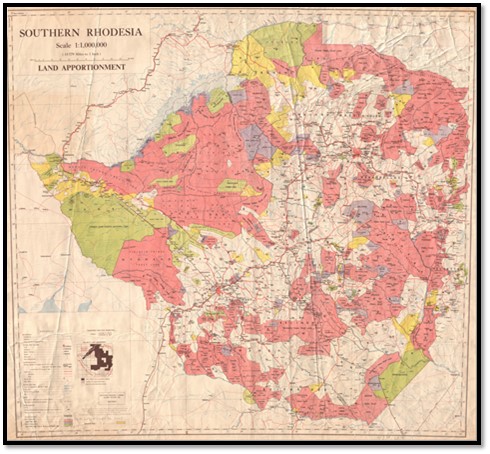

By 1925 the British South Africa Company (BSACo) had given 325,730 acres of land to church missions and they had purchased an additional 71,085 acres, although Chengetai Zvobgo points out that “much of this land was acquired without the permission of the African chiefs and their people.”[viii]

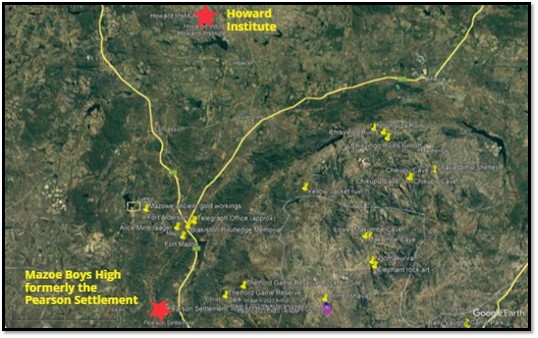

The Pearson Settlement Farm is given to the Salvation Army by the BSACo

Within three days of the Army arrival at Fort Salisbury Dr Leander Starr Jameson, then Chief Magistrate in Mashonaland, gave Major Pascoe the choice of a farm of 3,000 acres and two “stands” (lots) in Salisbury. In March 1892, Pascoe selected the best land he could find in the Mazoe Valley, north of Salisbury, that became known as the Pearson Settlement announcing that it was “grand country for the General’s [social] scheme.”

However even the BSACo’s favourable attitude toward the Salvation Army did not raise Major Pascoe’s hopes for success in Mashonaland. There were “no prospects” for religious work in Salisbury, certainly not among the whites, and he resigned on 5 July 1893[ix] after ceding a clear title deed to the farm from himself to the Salvation Army.

Adjutant Taylor was sent from Swaziland to succeed John Pascoe as the Army’s leader in Mashonaland. Taylor took along Captain Charlotte Ada Griffin, aged thirty-seven, to wed the farm manager at Mazoe, Captain Edward Cass, aged twenty-nine. The wedding took place at John Pascoe’s home and his friend Wesleyan Methodist missionary John White, officiated.

Progress prior to 1896

Misheck Nyandoro[x] writes that Captains Cass and Scott set about constructing pole and dhaka huts on the farm they had been allocated in the Mazoe valley, the traditional tribal area of chiefs Hwata and Chiweshe. Cass worked hard to learn Shona and was often away visiting local kraals; from these interactions with local people he was soon recognised by the white settlers as an expert on African customs and folklore.

Gradually their meetings began to attract larger local audiences and new converts were registered. Unfortunately fever was common during the rainy season; Captain Mahon and Scott both soon left, leaving just Cass and Crook at the Mazoe farm from the original 1891 party, although Crook also resigned and left within the next few years.

The 1896 Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) takes the settlers by surprise

The missionaries, as well as most settlers and the BSACo administration, considered the Mashona to be friendly and grateful to them for protecting them from the amaNdebele raids of the past. The spirit mediums, Ambuya Nehanda and Vasekuru Kaguvi in Mashonaland kept in close touch with the traditional religious leaders in Matabeleland, and missionaries of all denominations were shocked at the spate of murders in Mashonaland from mid-June 1896 and the attacks on their mission stations – there had been no previous signs of animosity between the missionaries and local people.[xi]

At this time the Mazoe farm was the only Salvation Army mission station in Mashonaland and Captain Cass and his wife were reluctant to leave, despite the call from Judge Vintcent for all settlers to gather in Salisbury.

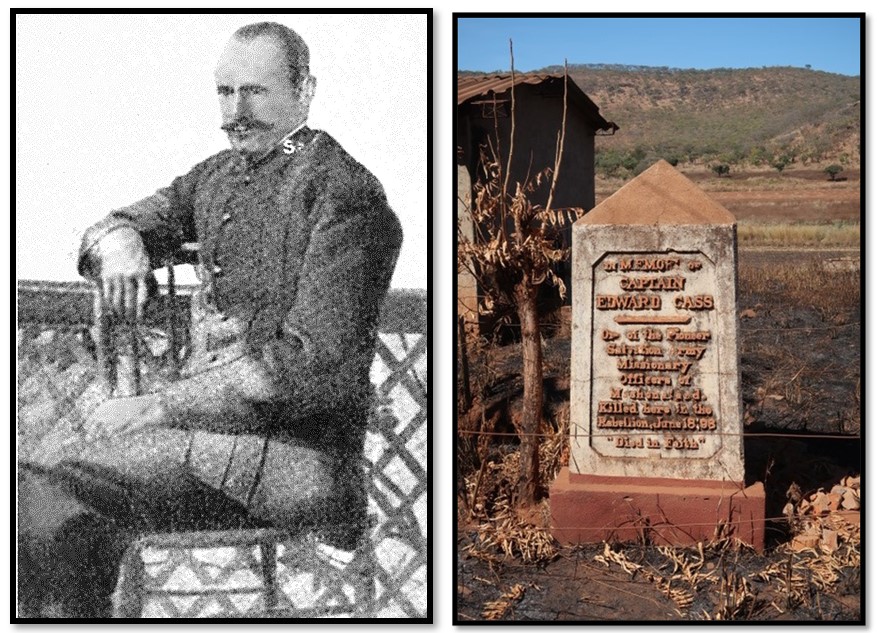

Captain Edward Cass, the Army’s first ‘martyr’ in Mashonaland

The first news which alarmed Salisbury was brought by a native who reached the six miles spruit late on the night of 15 of June 1896 with the report that Messrs Tate and Koefoed, with four native servants, had been murdered at the Beatrice mine by a group of twenty Matabele and Mashonas who came from chief Mashayamombe’s kraal armed with knobkerries. Judge Vincent obtained permission from Earl Grey[xii] to divert a portion of the Natal Troop, then at Fort Charter, to meet a patrol of the Rhodesia Horse under Lieut. Christison and attack Mashayamombe’s kraal at daybreak on the 16 June.

On that day news was received of the murder of John Stunt, a prospector, on the Hartley road. The Hartley native commissioner, David Moony, heard that three Indians who were trading near Mashayamombe’s kraal had been murdered and visited the kraal to make enquiries. What he saw confirmed the news, but he delayed to feed his horse, and was set upon. He was killed, but his detective, January, escaped to a cave and hid, and from there saw two prospectors, Stunt and Shell arrive at the kraal, where they were seized and tied up, and thrown into the Umfuli (present-day Mupfure) river.[xiii]

On 17 June Edward Cass was at the Vesuvius mine. He had a very modest Army allowance and was probably earning some extra income to support his new wife, something churches refer to as a “tent-maker” livelihood in which ministers earn extra in an auxiliary occupation.[xiv]

A telegram arrived at Mazoe telegraph office from Dan Judson, inspector of telegraphs at Salisbury, giving news of the Shona rising. The manager, J.W. Salthouse, who had nine men and three women at the Alice mine began to “fortify the position” and wired for a wagon. Salthouse told Captain Cass to bring his wife to the mine from the Salvation Army’s Mazoe Valley farm nine miles away. Cass returned with his wife at dawn on 18 June[xv] to join James Dickenson, the acting mining commissioner and his wife; his assistant H. Spreckley, Archer Burton, manager of the Holton syndicate store who was sick with fever and T.G. Routledge of the telegraph office. John Pascoe, the former Salvation Army leader, had been employed to move a ten-stamp crushing plant from the Vesuvius mine to the Alice mine at the mine along with Edward Cass, Stoddard, William Faull and Fairbairn. A Miner at the nearby Etna mine named Ffolliot-Darling and a wagon-driver named George and about a dozen natives completed the group.

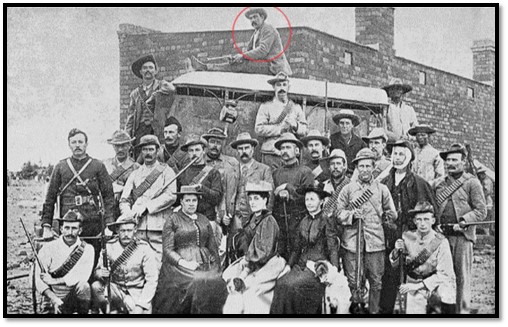

Some of those who featured in the Mazoe patrol rescue:

Standing (L-R) George, Niebuhr, John Pascoe, Salthouse, Ffolliot-Darling, Fairbairn

Sitting (L-R) Mrs Salthouse, Mrs Cass, Mrs Dickenson

Early on 18 June J.L. Blakiston of the African Transcontinental Telegraph Line, H.D. Zimmerman (later Otto Christian Rawson), the owner of a Salisbury general store and a “Cape boy” arrived with a wagonette sent by Judge Vintcent to take the wives of Cass, Dickenson, and Salthouse to Salisbury. It was now possible to get the women away and the whole party wanted to return to Salisbury. However, it appears they did not realise the seriousness of their situation as they started in separate groups instead of keeping together.

At about 11 am Dickenson and Cass who said they would act as an advance-guard, left on foot and were followed shortly afterwards by Pascoe, Fairbairn, Stoddard and Faull with the native carriers and a donkey cart. The three women, Mrs Salthouse, Mrs Cass and Mrs Dickenson left about an hour later in the spring wagon, Blakiston having given up his seat to the sick Burton. Salthouse as soon as the spring wagon left decided to ride across to the telegraph office and send a message to Salisbury and they all decided to have lunch before setting off on their 27 mile (44 kms) walk to Salisbury.

The donkey cart was about three miles from the Alice mine, the Iron Mask Range on their left and rocky, heavily-timbered slopes on their right when shots were heard ahead. John Pascoe sent a native ahead who saw Captain Cass and Dickenson being clubbed to death with knobkerries.[xvi] Their killers had hidden in the high coarse grass that flanked both sides of the road and attacked them.

Pascoe and his party rushed to the donkey cart around as their attackers ran down the track towards them. Faull who was driving gave a gasp and pushed the reins over to Pascoe sitting next to him before sinking back with a bullet through his heart. One of the donkeys was wounded, but it ran a mile before it collapsed and the team came to a stop. Behind them were the pursuing natives waving knobkerries, assegais and rifles. The three, Pascoe, Stoddard and Fairbairn abandoned the donkey cart and their dead companion, William Faull and ran for their lives.

About a mile from camp they saw the wagonette a few hundred yards ahead approaching a steep donga in the track and by waving and yelling persuaded the driver to pull up the mules and turn them around. The three man ran up, Pascoe climbed onto the top to look out for attackers, the others ran alongside and urged the mules into a fast trot. Inside the wagon were the three women, Mrs Cass and Dickenson who minutes before had been laughing and chatting were now sobbing with grief with the news of their husbands’ tragic fate. A brisk fire was kept up to discourage their pursuers from getting too close. The sound of firing alerted the others who had started towards the telegraph office and now dashed back to their little fort.[xvii]

For a detailed description of the siege read the article The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Photo from Christian Warfare in Rhodesia-Zimbabwe. Photo courtesy of Rob Burrett – the plaque reads:

Captain Edward Cass In Memory of Captain Edward Cass, One of the Pioneer

Salvation Army Missionary Officers of Mashonaland.

Killed here in the Rebellion, June 16, ’96. “Died in Faith”

On Saturday 20 June, the party of about thirty under inspector Randolph Nesbitt, started out at 9:30 am for Salisbury. Iron sheets on the sides of the wagonette protected the occupants from the constant fire of the Shona hidden in the tall grass on either side of the road. Two more men were killed, John Pascoe, on the roof of the wagonette, told the defenders when to expect ambushes.

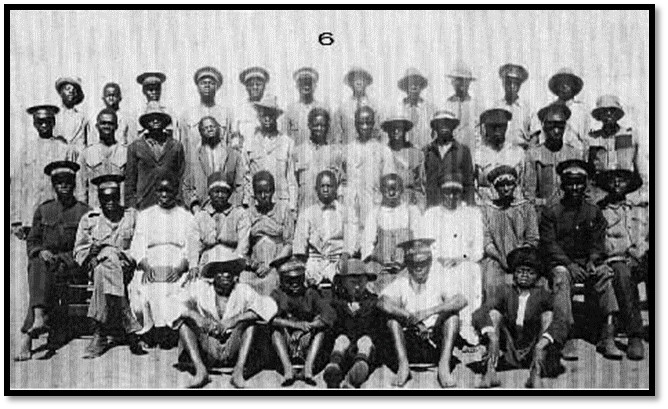

Photo National Archives of Zimbabwe. The Mazoe Patrol survivors:

Top L-R: Berry, Pascoe (circled on the roof of the wagonette) H. Rawson, George

Middle L-R: R. Nesbitt, A. Arnott, H. Nesbitt, O. Rawson, Ogilvie, R.A. Harbord, Salthouse, Fairbairn, Spreckley, Niebuhr, Darling, Coward, Hendrikz, Hendrik, Honey

Front L-R: Edmonds, Greer, Mrs Cass, Mrs Salthouse, Mrs Dickenson, D. Judson, Pollett

Aftermath of the death of Captain Cass

The Salvation army erected a monument to the memory of Captain Cass on the Tatagura road where he died and near the Mazoe Valley farm he had managed. The Salvation Army Mazoe farm was later named after Colonel William J. Pearson, a British Salvation Army leader, who never visited and has no known association with the country.

In grief, Mrs Ida Cass returned to South Africa in September 1896. Adjutant and Mrs Taylor continued at the Mazoe farm, but fever forced them also to return South Africa in December 1896, and for some years the farm was deserted.

In 1901 the farm reopened under Staff Captain and Mrs Frank Bradley with Adjutant and Mrs Mbambo Matunjwa to assist. In 1908 captain and Mrs Ben Muhambi became the first African officers in Matabeleland and the following year two African officers were appointed to Salisbury’s Shona townships. The Salvation Army had switched its attention from white settlers to evangelizing Africans living in the reserves and urban areas.[xviii]

Leonard Andrew Kirby Senior, early life, marriage and transfer as a Salvation Army Captain to Rhodesia

Dad was the third child from his grandfather’s second marriage, and was born on 9 November 1885 in Leyton, London. His working life began at the age of 14 as an office boy for 7/6d a week, but in 1907 aged 21, he sailed for Canada working on a farm, later as a gardener, then on a passenger ship sailing the Great Lakes and made seventeen round trips to Fort William, then worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway as a special service private before going south and working as an ice-man at the Grunewald Hotel in New Orleans, before returning to Brantford, Ontario and working for Massey Harris doing woodwork jobs. He did cement work for the City Council of Brantford, then in a brick factory before going to Vancouver where he found a job on the passenger ship, the SS Princess Charlotte as engineer store-keeper, responsible for stores and supervision of the firemen feeding the ship’s boilers.

Dad writes, "I was in Vancouver one Sunday morning in 1911 and went up town. I was standing on the main street when the Salvation Army Band came near where I stood, playing ‘Lead Kindly Light’ and God spoke to me. I prayed to God to help me be a better man - not much of a prayer - but I was in earnest and meant it. God answered and soon after that I returned to Brantford.” There he got a good job ,and sought out the Salvation Army, where he was made welcome, and after being enrolled as a Salvation Army soldier, he taught in Sunday school, and assisted with services in the Brantford Prison.

One evening, after the service, one of the old soldiers of the Corps went up to Dad and said, "Will you see Rose Field safely home this evening?” to which he said "yes," then this man went to Rose Field and said, "brother Kirby will see you home tonight". He says that it was a long time before either of them discovered the trick that had been played on them and continues, "But afterwards I saw in it, God's plan for my life."

Rose Emma Field had been a Salvation Army Officer in England having trained in 1908 but resigned to go home to nurse her mother. She later immigrated to Brantford with friends and joined the Brantford Corps. "We were married in the Baptist Church on Terrace Hill on Oct 1st, 1914. One could not be married in the Salvation Army Hall in those days". Neither of Dad’s parents, his brothers, or sister, would go to the wedding and he goes on to say, "We went into our new home on Huff Avenue which had been built mostly by myself with new furnishings from Eaton's, all paid for." On 27th July 1915 their first son, Leonard Field Kirby (the author) was born.

Dad continues his story saying "Soon after our son's birth I felt the call of God to become a Salvation Army Officer which I tried to throw off, feeling that I was not suited for such work, forgetting that if God calls, he fits us for that call. The call of God was so strong that at last we decided to sell the house and go to England and apply to the Salvation Army.”

But Dad’s old boss came to see him and persuaded him to take charge of a farm. He says he tried to resist the call of God and started this other job. It was here that Rose, their second child was born on 22nd June 1917. Then came the terrible flu epidemic of 1918 and many people died, temporary hospitals had to be put up. Dad himself was stricken with flu and double pneumonia, the doctor said there was no hope for him. He writes, “I felt I was dying and said to myself, what a fool I am, I should have fully obeyed the call of God, and there and then I said Lord, if you spare my life, I will go.” He was spared, he kept his promise, they sold all their furniture and set out for England"

Dad was accepted at the Salvation Army Training College in Clapton, London. Mum stayed with relatives as she had already completed training. On 6 May 1920 he passed out with the rank of Captain and they left for Rhodesia the same month, taking the Carisbrook Castle for Capetown and then a 5 day train journey to Salisbury, Rhodesia, that was reached early in July 1920. Here, his first responsibility was the training of African Cadets at the Officers Training College at the Salvation Army’s Pearson farm.[xix]

Early Days at Pearson Settlement from 1920-1923

Here the author picks up the story. The family stayed initially with Major & Mrs Bradley, the Major being in charge of Salvation Army work in Mashonaland, and once the Major had a bicycle for Dad, they cycled out to the Pearson Training College. Dad was the training principal for 35 cadets in 1920 with responsibility also for all the Salvation Army work in the nearby Chiweshe and Chinamora Reserves.

There was no house for the family, so Mum, Rose and I lived with Adjutant & Mrs Thompson. He was responsible for the Pearson Farm, which had been donated to the Salvation Army by the British South Africa Company under Cecil Rhodes, and the Thompson's were the only other white officers in Mashonaland, with just Major & Mrs Barker in Matabeleland. They travelled from Salisbury to Pearson in a Cape cart drawn by two mules, this was their only form of transport for the next five years.

Captain Edward and Mrs Ida Cass

Near where they lived were the remains of the small compound where Captain Edward and Mrs. Cass had been living in 1896 as the first white officers to live at Pearson. When the Shona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) broke out they remained feeling quite safe amongst all the Mashona people. However, all whites were ordered to go to the Alice Mine at Mazoe, a dozen or so miles away, so they complied. A relief party was sent out from Salisbury to escort them from the Alice Mine back to Salisbury. Nearing Pearson, Captain Cass left the party to take a short cut home to collect some things and was murdered on the journey on 16 June 1896. The old Cass site with its aloe plants was a constant reminder to the author of the sacrifice made by this officer. Later a monument was erected about 4 miles from Pearson where his body was eventually found.[xx]

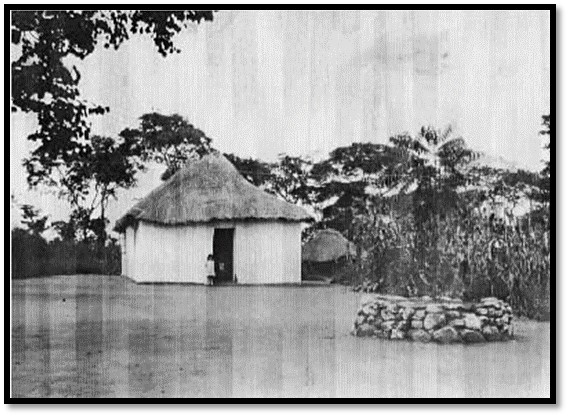

Their home at the Pearson Settlement

Dad cleaned out two small rooms at the back of the Training College Hall where we stayed until two pole and dhaka thatched huts were built for us, the doors made of grass were tied closed with a length of string, but no one ever stole anything, although we would be away for a week or ten days at a time when the cadets went into the reserve. These huts were home, while clay bricks were made and burnt, and a fine red brick house built for us.

Mum cooking breakfast at Nyakudya in the Chiweshe Reserve with the cadets.

Mum, Rose, me and Lily, the Cape cart in the background

The building went very slowly as the family often accompanied the cadets who would walk, Dad would be on his bicycle, and Rose and I in the Cape cart with Mum driven by one of the cadets with no chance of breaking the speed limit. We would leave Pearson very early in the morning and it was usually after dark when we arrived in the Chiweshe Reserve, near present day Howard, a distance of about 30 miles. Sometimes even the Cape cart was stopped, because there was no road, and we would end up walking, mother became a great walker, but Rose and I would tire and be carried by one of the cadets.

When Dad had an attack of fever, Mum walked 5 miles for a planned evening meeting and then walked home in the dark. One time when the mules had run away, the family walked back 30 miles, Dad pushing us children on his bicycle. The mules were later traded for more reliable, but slower, donkeys. The author says local Mashona were always kind, bringing gifts of eggs, chickens, vegetables, pumpkins, mealies and milk.

On 28 January 1923 a second daughter, Lily Field (Mazoe) Kirby, was born at Salisbury’s General Hospital. Mum accompanied Dad with the three children when the cadets went for training, and baby never gave any problems.

In 1923, Dad employed some teachers and started a school with accommodation for boarders, and this made Pearson even more unpopular with the local farmers, who made constant complaints to the authorities about their presence. He wrote, "The farmers, as well as the police, claimed that we were spoiling the Africans by educating them, and making them lazy by letting them go to school instead of going to work, and the police threatened to have the cadets put in prison sooner or later." A white policeman actually stabled his horse in one of our churches to show his disrespect and he goes on to say, "I was so sick at heart about this opposition that I just knelt down in the veldt and prayed as I never had prayed before, and I asked God, if possible, to find us another place where we could carry on our work unhindered. I got up feeling at peace. Imagine my surprise when 3 days later the Native Commissioner from Mazoe called me to say that he felt we were in the wrong place, and if we were prepared to move we could have 100 acres of land to move to anywhere in the Chiweshe Reserve."

Land apportionment in Rhodesia 1963,

https://digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za/islandora/object/islandora%3A25...

Headquarters approved a move and Dad, accompanied by Major Barker who had succeeded Major Bradley, went into Chiweshe to talk to the headmen about various sites and having located a suitable site near Nyachuru requested the promised 100 acres. This was granted, and soon arrangements were made for the transfer. The students and cadets were assembled and told about the move to the new site but it was made clear to them it was voluntary. All 75 cadets or students decided to go, despite a 35 mile walk and the buildings having to be constructed from scratch.

On moving day an ox wagon carried a load of classroom furniture and equipment, as well as the Kirby family’s own meagre possessions. The cadets and students walked; Dad went off on his beloved bicycle. Mother, Rose, baby Lily, and I went in style in Major Barker’s Model T Ford which he had just purchased. Local Salvationists and their families cut a track for the Ford, the first car in the area. Dad went ahead and had a pole and dhaka hut built so the family were not sleeping in the open. With their move to Howard a new chapter begins.

Google earth map of Howard Institute and Pearson Settlement, now Mazowe Boys High School

Mazowe Boys High School

The Salvation Army retained the title deeds to the Pearson settlement despite moving the bulk of their activities to the Howard institute in the Chiweshe Tribal trust Lands (present-day communal lands)

From its humble beginnings in 1922 under Captain Leonard Kirby as superintendent, and ensign Kunzvi Shava as native teacher, with thirty-five boarders, the school has kept its christian values and gone forward to become one of Zimbabwe’s leading schools. The Wikipedia entry states it was originally “an adjunct to the corps (church) program at Pearson farm. The Salvation Army missionaries founded the school to ‘keep the mission going and the church-going.’ In addition, it founded the school to compete with other missions that also had schools for ‘natives’ such as the Methodist, the Seventh-Day Adventists, the Anglicans, the Church of Sweden, Matopo Mission (Brethren in Christ), Presbyterian, and the African Methodist Episcopal. By 1953, religious organizations were responsible for 98 percent of all [African] elementary education in Rhodesia and the Salvation Army was sixth in the number of students with 14,600. In 1959 the army transferred the school to the Pearson farm, to the site of the late-nineteenth-century mission buildings that the Salvation Army left in the area in 1923. The school’s new name was Mazowe Secondary School.”

Today Mazowe High School is counted academically as one of the top twenty schools[xxi] and with its wide variety of sporting and extra-curricular activities, including school band, choir, chess, current affairs club, debating society, Lion Clubs International, Rotary International, Scripture Union, Toastmasters International and Youth against AIDS [xxii] turns out especially rounded and accomplished young men who are well-equipped for the modern world.

Founding the Howard Institute (1923-5) at Nyachuru in Chiweshe Reserve

Everyone moved to the new site in the latter half of September 1923. All the items on the ox wagon were unloaded on the ground near the site of Nyachuru kraal, before it turned back to Pearson to collect the remaining school furniture, ploughs, other farming implements and maize supplies. That evening all the men cadets[xxiii] and their wives, students and teachers just laid themselves down under trees and slept in blankets around the fires.

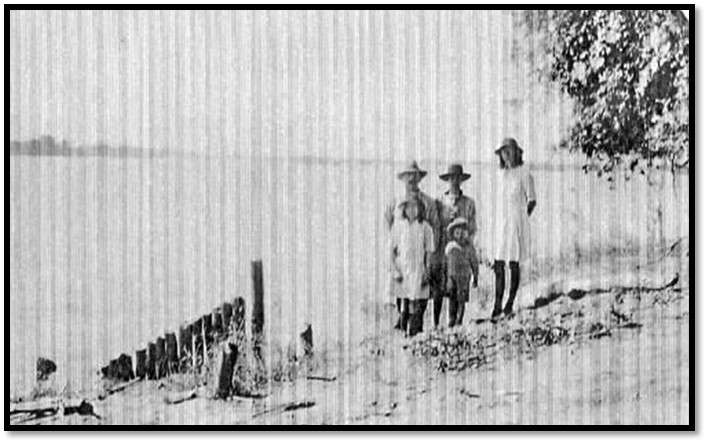

Ruya river, Chiweshe Reserve in the Cape cart pulled by mules. Me, Rose, Lily, Mum

Next morning everyone got to work cutting poles about 8 ft. long that were packed closely together in a circle about 10 ft. in diameter to form the hut walls. Mud, known locally as dhaka, was then collected and packed by the women between the poles and pounded into the ground for a floor. Others collected thatching grass up to 9 ft. long for the roof and this was laid by the men onto a wood frame. There was an urgent necessity with the rainy season beginning after mid-November, but gradually a small hastily erected village began to take shape.

Kirby family early days at Howard Institute, Dad, Mum, me, Rose and baby Lily

The Kirby’s decided the thatched hut was only very temporary as donkeys came from Nyachuru village and ate the thatching grass, chickens laid their eggs under the beds, although that could be seen as a blessing, and the wood-fired Dover stove had to stay outside the pole and dhaka hut. So Dad taught some of the cadets to make sun-baked Kimberley bricks[xxiv] from clay. Once they were dried, a two-roomed house was built, with small windows covered in calico and a thatched roof, the interior walls were unplastered, the floor pounded dhaka and the door made from wood packing cases. As the thatch often leaked, the beds were covered in grain bags and the floor could become muddy. Nevertheless, it was a great step forward.

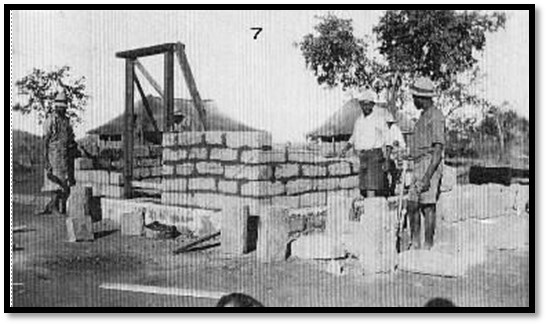

Very quickly Dad drew up a site plan for the layout of the roads and the location of houses, classrooms, hall, kitchen, washrooms and pit latrines as it was envisaged this was going to be a thriving centre of Salvation Army work. For this large numbers of Kimberley bricks were required. The clay came from a site by the river, and as soon as they were dry, they were transported by ox drawn sleighs.[xxv] Despite the difficulties, 27 Kimberley brick buildings with thatched roofs were erected that first dry season, only the classroom was roofed with corrugated iron. There was no transport to bring window and door frames from Salisbury, so they were all cut from poles and dressed with an axe or adze, and the doors made from wood packing cases.

The first Kimberley brick houses at Nyachuru (Howard) the trade students taught by Dad to make them

Naming the Howard Institute

With the imminent arrival of the territorial commander from Cape Town, a large wooden board was erected with Nyachuru Training Institute. He however, wanted a different name, and suggested the Howard Institute after the chief-of-staff of the Salvation Army at international headquarters in England who retired in 1919. Dad objected because he felt Commissioner henry Howard had not done anything for Mashonaland and had never been to the country. If the name had to be changed from Nyachuru, the name local people called the village, he preferred it be called the Bradley Institute, local people agreed as Major Bradley had spent many years establishing the Salvation Army in Mashonaland, travelling around on his bicycle, living on African food, and sleeping on the floor of native huts that the people made available to him. They were overruled and so Howard Institute became the new name. However, Dad was told that the next Salvation Army Institute would be named the Bradley Institute and this promise was kept.

The Hall built at Nyachuru (Howard) with an ox span hauling logs on a sleigh

Howard Institute by 1925

The place developed rapidly into a thriving community with more and more students applying for admission, its wide roads lined with young Jacaranda and Toona[xxvi] trees and the Kimberley brick buildings on each side. Most adult students had no previous education and started with the basics.

Howard in 1925, the building with corrugated-iron roof was the first classroom. Dad and Capt Erikson building the principal’s bungalow

I first went to school at Howard aged 9 years as a lone white child with an African teacher who had no more than three, or perhaps four years schooling himself, and practically every other pupil was an African adult. Education for Africans in those days was in its infancy.

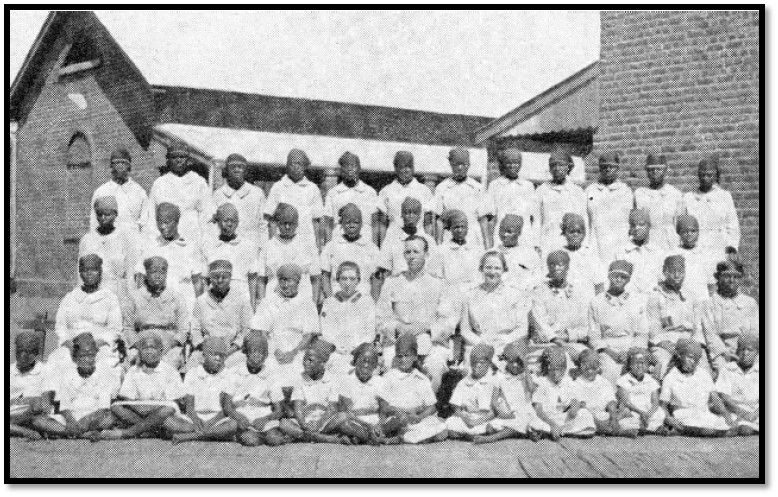

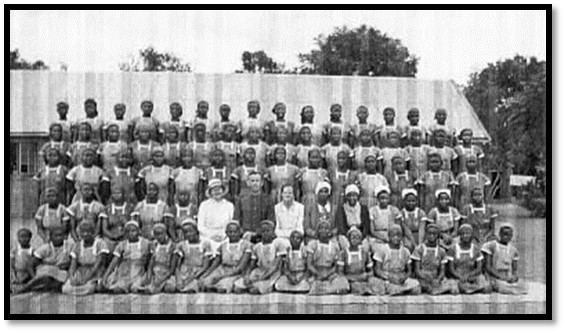

My first school class photo with the cadets and our teacher, Matthew Magorimbo

We were happy to be there and felt appreciated by those we lived with. For the first eighteen months we never travelled to Salisbury, relying on locally grown vegetables and using the gun to hunt for some meat occasionally. Zebediah Mujeranje came as a young man and would ride by bicycle the 12 miles to Glendale, once and sometimes twice a week, to collect mail or supplies from the one small store. Zebediah stayed on the staff for the rest of his life becoming the Salvation Army’s official translator and when Howard became a Teacher Training College he was an excellent vernacular teacher.

At this time Dad gave me a second-hand bicycle that became a valued possession. It had no mudguards back or front, and no brakes, but it did have a bell. When Dad went on tour I could travel along with him on my own bicycle.

The Howard Salvation Army band

The British South Africa Police band in Salisbury were selling off some of their older instruments quite cheaply and Major Barker contacted Dad to see if he was interested in forming a cadet band. The cadets were very excited about it and put on some concerts in a record time of 3 days, raising the twenty-seven pounds to buy seven musical instruments, and a drum and a Salvation Army Band was formed. A Bulawayo cadet played an instrument and taught the others. I learned to play one or two tunes the band had learned on a cornet. The Salvation Army in New Zealand heard of our efforts, and donated a further thirteen instruments, and by the time we left Howard, we had worthwhile band which quickly drew crowds wherever it went.

Crops are planted

Whilst the buildings were being erected, the dense bush was cleared, not only to help control the mosquitoes, but to prepare the ground for planting crops for food and income. When the rains arrived, maize, beans and monkey nuts (peanuts) were planted for food and also cotton as a cash crop as the soil was good for cotton growing.

Medical help

There was much sickness in the early days from malaria and also burns, particularly to children from rolling into the open fire at the centre of the hut. Also, accidents from axe cuts and other injuries. Villagers would be waiting outside our house early in the morning before we were up and would cough for attention. Although my parents had no special medical knowledge, they did their best with the few remedies which they had, many of them old fashioned such as mustard plasters, which was Dad's favourite, and very effective for severe chest colds or pneumonia.

In July 1925 I was holding a hurricane lantern for Dad putting on a door in a new house, when I started shivering and felt very cold, so we stopped working and went home. Nothing made me warm and when they saw my urine was as black as ink they knew that I had black water fever.[xxvii] The kidneys are usually severely damaged– the medical advice at the time was not to move the patient. Mum and Dad knew immediately the seriousness of the situation and after prayers for guidance at about 3am asked Zebediah Mujeranje to take a message to Major Barker in Salisbury, a little over 50 miles away and ask him to bring his Model T Ford and take me to hospital. Zebediah set off immediately and arriving early at the Major's house handed over the letter. Major Barker wasted no time and travelled as quickly as he could on the primitive tracks breaking a spring on the way. The track was so rough I needed to be held down to prevent being thrown off the seat and at just after 8am we arrived at Salisbury General Hospital.

The doctors thought there was no hope of my recovery. But word soon spread amongst the Salvationists in Salisbury and a prayer meeting was called to pray that the Lord would spare my life. The Lord saw fit to hear those prayers with the result that three weeks later I had fully recovered and was out of hospital. Many years later I was told by my mother that in that prayer meeting she prayed and said to the Lord, "if Leonard is going to grow up to be a bad person take him now, but it is our desire that he be spared and that he becomes a Salvation Army Officer to work in Africa to help the people of this land.” It was not until I was actually an officer back in Rhodesia that my mother told me about her prayer because she did not want me to be influenced in my career decisions.

Dad had applied for four hundred pounds to build a much needed clinic and the money arrived just as we went south to the Cape - it was left to Dad's successor, Captain Kimball, to open the first clinic at Howard.

Howard High School

Two years later the Salvation Army opened its first secondary school, housed at Howard Institute in the Chiweshe Reserve. The Wikipedia entry states that currently Howard High School has approximately 800 students, most of them boarders in houses that are named after birds of prey.

Howard High School gets great academic results at Junior Certificate, which is administered by The Salvation Army Schools Association, then Ordinary Level and Advanced Level, coordinated by The Zimbabwe Schools Examinations Council.

The Kirby family leave for Cape Town

Soon after my recovery the territorial headquarters decided we should move away from Howard because all the family had suffered from malaria and Dad was appointed to the Rondebosch Social Farm just outside of Capetown – it was hoped the climate and sea air would restore our good health.

A letter dated 2 September 1925 from Commissioner James Hay to Dad went as follows, “I have had information showing me the urgent need at Rondebosch and this has compelled me to alter your appointment. For many reasons I would have liked you to go to Maritzburg, but I am sure that as second officer at Rondebosch you will have a great opportunity. Colonel Lotz has been ill and is still far from well although back at Rondebosch. He will, I am sure, be able to further develop your farming knowledge, and you will take to that place a willing mind and ready spirit. You will find fit and reasonable school facilities and this will be a comfort to you both. You can take your furlough at the Cape and you will be well and thoroughly recommended at the People’s Palace.[xxviii] We will write to Staff Captain Symmons and you can go direct there and then proceed to Rondebosch in October.”

The journey to the Cape by train took five days to travel the 1,650 miles. We had our own food; the compartments were fairly comfortable on the train with the five of us having six bunk beds to ourselves. Bechuanaland (present-day Botswana) was hot, but if you opened the window instead of cool fresh air you would get smoke from the engine. Initially the countryside was dry and uninteresting, but the last part in the Cape as we went through the mountains was enjoyable, and the change in altitude from the Howard at 5,000 ft. to sea level was a very pleasant change.

The People’s Palace hotel was owned and run by the Salvation Army near the centre of Cape Town and we had a wonderful holiday. The city was such a contrast from the isolation of Howard. The large shops, trams and other traffic, the lovely flowers and abundant fruit in the market, grapes were selling at 6 lbs for a shilling. We enjoyed lying around on the beach, especially at Camps Bay and Muizenberg, and by the end of the three weeks we were all feeling so much better.

Rondebosch Social farm (1925-27)

We were only five miles from the centre of Cape Town, just a few minutes ride on the train. The Social Farm was run by the Salvation Army to help men who had been in trouble with the law or had problems with alcohol. They worked on the lands growing crops and there was a large dairy herd with four milk carts going out daily delivering milk in the early hours of the morning while it was still cool.

My sister Rose and I were soon attending good schools. Rose in Std 1 and went to a nearby girls school and I was in Std 2 at a boys school some distance from the farm that I travelled to on a brand new bicycle. I joined the band of the Claremont Corps, but then changed to the junior band in Cape Town and was finally promoted to the senior band, even though I could not read music. I would go into Cape town in time for the morning prayer meeting, then spend the day at the men's hostel. On Sunday evenings we played at the pier, where an open air meeting was held by a fountain, and there was usually a good crowd standing around to listen.

Furlough to England and Canada – we meet General Bramwell Booth

The Salvation Army regulations governing homeland furlough in those days stated that you were granted six months holiday at the end of seven years if you were engaged in missionary work, but not if you were engaged in other Salvation Army service. Because my parents had spent over 5 years doing pioneer missionary work in Rhodesia it was agreed that they would be granted homeland furlough in 1927 with all our fares paid on condition they went back on missionary work upon their return to Africa.

Whilst Dad and Mum were at international headquarters all the family were taken into General Bramwell Booth's office where he asked them about their work in Rhodesia. The General spoke to us children and gave us a book `Jesus of Nazareth' which he signed. Unfortunately nobody in the family knows what happened to the book. I remember as if it was yesterday standing beside this great man with his hand on my head as he prayed that the Lord would guide and direct my life.

The Kirby family return to Howard

Although the hierarchy wanted Dad to return to Rondebosch, he had to honour his promise and return to work among the African peoples of Rhodesia, so by November 1927 we were back at Howard where many changes had taken place in the two years we were away and Dad assisted Captain Kimball for six months. By this time the importance of Howard was realized and money had become available to erect a number of fine red brick buildings, including our house. The clinic was functioning with Adjutant Battersby, a nurse from New Zealand, and there were other missionaries on staff. Captain Kimball, an electrician by trade, had secured funds for a generator, so we had lights until about 9 pm every evening in the houses and on the streets. Batteries, which were charged while the generator was running, gave each house a limited amount of electric light throughout the night. The road to Howard had been improved, they had a vehicle and the school and cadets college were expanding and improving their standards with better qualified teaching staff. When Dad went there he was told that they wanted him at Howard for a special purpose (which they explained to him) and that it would just be for a few months.

Transferred to Salisbury

In April 1928 Dad was appointed to take charge of the Salisbury European Corps of the Salvation Army, but again it was temporary. However it did mean Rose and I went back to school. Rose to Girls High School and I to Prince Edward Junior School.

Whilst Dad was Corps Officer in Salisbury, Commissioner Lucy Booth-Hellberg visited Rhodesia. The daughter of our founder General William Booth, she gave a lecture entitled "My Father" which was well attended by the general public.

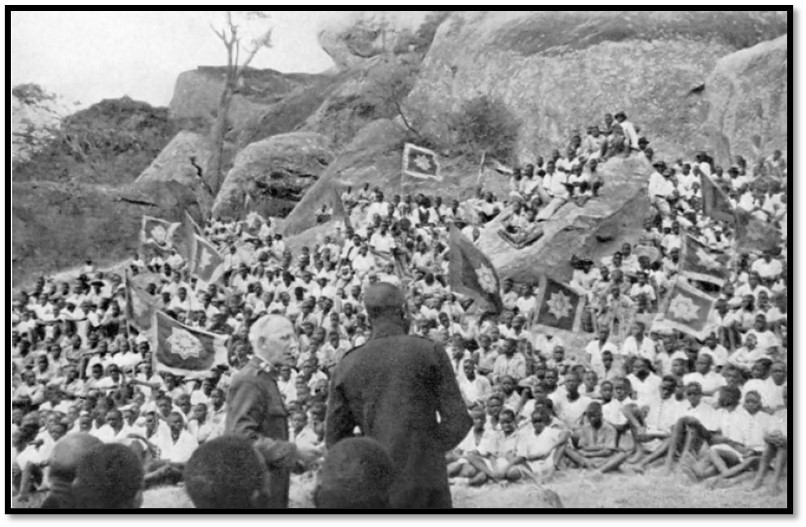

This was followed by a great Congress meeting at Howard which were attended by thousands from as far away as Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) My most vivid memory was the official opening of the enlarged clinic at Howard. Commissioner Lucy decided she would ride to Howard, so it was arranged for two horses to be borrowed from the BSAP at Concession, twelve miles away. One of the horses was dark brown, the other one was white and a bit unpredictable. The police suggested that Commissioner Lucy ride the brown horse, but she would not hear of it, and said Commissioner de Groot would ride the brown one, she would ride to the opening of the clinic on the white horse. A large crowd was gathered when they arrived at the clinic entrance for the ceremony. But on Lady Lucy dismounting, the horse bucked and our founder's daughter went over the horse’s head and landed on the clinic steps. Fortunately, she was only badly shaken up and not hurt, this incident never made any of the newspaper reports, but we had many good laughs afterwards.

NAZ: Salvation Army congress meeting near Howard Institute in the late 1930’s

Transfer to Sinoia, present-day Chinhoyi (1928-30)

On 23 July 1928 our brother Andrew Howard was born and about 3 months later we were on the move once again.

Dad was succeeding Captain Walton as district officer in charge of Salvation Army activities in the Magondi and Sipolilo Reserves, at some of the mines and the Sinoia Township.

Our quarters were in the African area near the Salvation Army Hall. It was called a piza house and had been erected by Captain Walton. They were so easy and inexpensive to erect requiring strong wide boards and some half inch bolts about 12 or 15 inches long according to how thick you wanted to make your walls. Damp soil would be rammed down between the boards with as much heavy pounding as possible until all the space was filled, and if the soil was pressed firmly enough the boards could be unbolted and taken off right away. The bolts would be pulled out of the wall then another section built. Within a week of so all the mud walls would be standing straight up, and after a few days drying in the tropical sun a roof could be put on. Such was the house we moved into.

The Salvation Army hall at Sinoia, a piza building

Often poison was added to the earth to kill the termites which would make nests in the earth wall and eat anything available, furniture, clothing, mats and even leather shoes! When Andrew was a year old he tried eating some of the wall and the poison almost killed him, fortunately the hospital was close.

One Sunday afternoon Dad moved a cushion from a chair and a Mozambique spitting cobra[xxix] reared up in front of him and shot venom into his eyes, completely blinding him. He shouted to us children to get into the bedroom and shut the door, before remembering reading how someone else saved his eyesight by pouring milk into his eyes. Blinded, Dad felt his way to the kitchen and poured milk into his eyes, the poison clotted and he was able to pull most of it out in strings. This gave him partial sight and he walked to the hall door where a service was in progress and called for help. The cobra had not moved and was soon killed. Fortunately, Dad suffered no after effects and at the age of 85 he could still read a newspaper without glasses. Providence led him to read the article about milk to cure cobra venom just a few days before the snake had blinded him. Snakes were common in the area then.

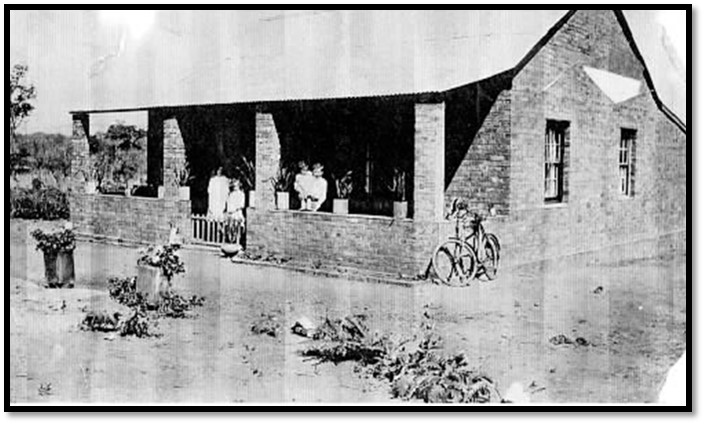

We build a new home

We only lived in the piza house for about a year before Sinoia town council allocated the Salvation Army a plot in the white residential area and near my school. A budget of one hundred and fifty pounds was granted by headquarters for a three bedroom red brick house, but did not allow for labour, so Dad and I did all the work ourselves. I went to school in the mornings and came home at lunch time and spent the rest of the day building. The money covered bricks, cement, lime for mortar, and roofing, but we had to get the doors and windows from the piza house and cart them two miles in the car to the new site meaning we lived for a couple of months without any doors or windows! What a joy it was when we moved into the new house and that house remained the divisional commander's quarters until 1960 when Isabel and I were appointed to Sinoia, when I built new quarters and turned the old house into offices.

The house built by Dad and me at Sinoia, Rose, Lily, Andrew and myself in the photo

Our Model T Ford

With Dad’s new duties came his first car, the Model T Ford that Major Barker had used to take me to Salisbury Hospital when I had black water fever. The vehicle had now accumulated a great mileage and Dad had to learn how to drive. No driving licences were issued in those days, so only limited knowledge was required, and the great thing about the Model T was that there were no gears to grate. There were just 3 pedals, one was the brake, one was low gear when pushed in and top gear when out, and the centre pedal was reverse. They all operated by belts tightening on a drum, so even pressing reverse when going fast forward did no damage, but just slowed the vehicle. I think I managed to drive the car sooner than Dad, even though I was only 13 years old and, in fact, I did most of the driving the whole time we lived in Sinoia!

The roads outside the Sinoia, apart from the main road to Salisbury, were very poor, so we seldom used the car in the rainy season when it was so easy to get stuck in mud. Dad arranged many of his trips during school holidays, although on occasion I missed some school. We strapped our bicycles on the side as we never knew when we might need to go for help. The car went seldom into the reserves because of the lack of roads, often we left it at a farm and went by bicycle. Our Model T Ford had wooden spokes on the wheels, in the dry season before going on a trip we soaked the wheels in water for the night, so the wood swelled and gripped the rims better. Dad's mechanical knowledge was limited, so if anything went wrong with the car, it was my duty to diagnose the problem. Fortunately although I never had a single lesson in mechanics, things came naturally, and somehow we kept the car running. The engine crankshaft had worn so oval, in the middle of nowhere, I often had to open the sump, drain the oil and tighten the bearings, because they made so much noise. That would be impossible on modern cars, but the Model T Ford was a great vehicle with plenty of clearance, so it could go places where only a 4 wheel drive would get today.

One day with the whole family in the car at Banket, the crown wheel in the rear axle stripped. Fortunately there was a small store and garage, these problems with Fords were quite common and they had parts in stock. The car was pushed over to the garage, and the job was completed in good time, we paid the bill and all got in for our drive home. The car started up immediately, but instead of going forward, we went backwards. The axle had been put in the wrong way around, but I put it in reverse, and we drove home! Next day it was brought back, and the axle turned around, enabling the vehicle to go in the right direction.

At the Copper Queen mine there was a very steep hill and the fuel would not run to the carburettor, so we always reversed backwards so the fuel would run from the tank to the engine! It was a long bumpy ride in reverse up that steep winding road to the crest of the mountain, but very few cars used that road.

Our bicycles took us into the African Reserves

We often left the car at Ethel Mine[xxx] where the Salvation Army had a Corps and a school for the children of the African mine workers after the mine management built a good classroom. We often slept in the classroom before a setting off next morning. The asbestos dust in the air at the Ethel Mine was just like a thick fog and we know today is hazardous to health.

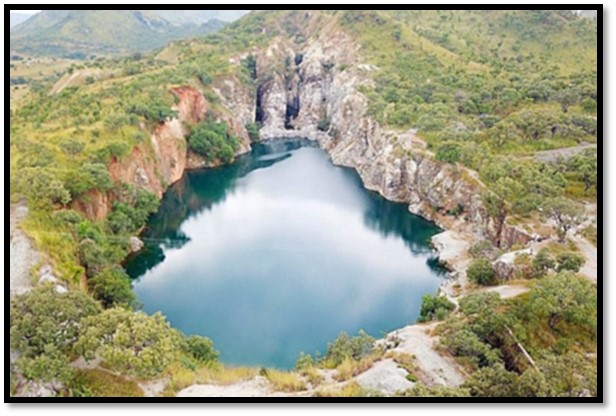

The abandoned quarry at Ethel mine

Sometimes we cycled 50 miles in a day, with our food and blankets strapped on our bicycles, and spending a few days going from one group to another doing night meetings, dealing with any problems, and inspecting the primary school next morning. Most schools only went up to Std 2 in those days. Local people were always very friendly and pleased to see us and brought us food. We carried bread and butter as they were unobtainable in the reserves. Travelling by bicycle we really got to know the people and they appreciated our effort to visit them. Today, with good roads and reliable vehicles, visits are much shorter, and usually the divisional commander returns home at night, so he is not so well known by the local people.

Sinoia High School

We had a very fine school in Sinoia (now Chinhoyi) the majority of boys and girls were boarders, as their parents lived on farms or mines. I was two years there doing Std 4 and Std 5 and I really enjoyed my time there. Mr Pocock was also the scoutmaster and took the scout troop away into the surrounding hills camping at weekends, that was a great experience. We went to the Hunyani river (present-day Manyame) just east of Sinoia, where we learned tracking skills and sent signal messages from one kopje to another. We often saw crocodiles asleep on a sandbank and waiting for wildlife coming to the river for a drink.

Sadly Mr Pocock was killed and greatly missed. He often went to a friend’s farm to hunt wild pigs as they were a great menace to farmers in their maize crops. One day the farmer forgot to tell his nightguard that Mr Pocock was coming to hunt before dawn. It was still dark when the nightguard heard rustling in the maize, thought it was wild pig, and fired his gun. Mr Pocock was killed instantly. His son was about the same age as I and we were very upset, our scout troop was never the same after our scoutmaster’s death.

Sinoia was a good place to live, but after a few months in our nice new home, word came again that we were to move and in 1930 we made our way to Pearson where Dad was given responsibility for the farm.

Pearson Settlement Farm (1930-34)

Pearson Farm which was over 4,000 acres (approximately 3 miles wide and over 3 miles long) had been donated to the Salvation Army by the British South Africa Company. Major & Mrs Pascoe came from Kimberley in April 1891 to begin Salvation Army work and were granted this farm at the headwaters of the Mazoe Valley.

Farming full-time was a new kind of experience for Dad although he had farmed a little in Canada, as well as Rondebosch Social Farm for nearly two years.

I take up farming full-time

I was now in first year of High School and arrangements were made for me to stay with the Stivenger family, who lived in Ardbennie. Each day I cycled the five miles to school, and sometimes I cycled the eighteen miles to Pearson on Friday afternoon, returning in time for school on Monday morning. By the end of 1930 I decided that I preferred farming and this brought my school days to an end…in all, I spent less than five years in full-time schooling.

The only vehicle at Pearson had come to the end of its life, so in 1931 a new Model A Ford half ton truck was bought costing one hundred and fifty pounds. A driving licence was now a legal requirement, so soon after my sixteenth birthday, Mr Thornton, the approved driving licence examiner took me around a few city blocks, during which time I only saw about four other vehicles and left with my driving licence. After that, Dad would seldom drive, if I was available.

The farm always had three full spans of sixteen oxen to pull a three-furrow plough, or a fully laden ox wagon. Before we had the van, the ox wagon went to Salisbury for supplies and would be away for two full days, as the oxen travelled so slowly, and needed frequent rest stops, if they had a heavy load. If we required a small item, such as a part, I could cycle to Salisbury in the morning and be back by lunch time. On Sunday morning I cycled into Salisbury to join the band at the open air morning service meetings and would be back at Pearson after the Sunday morning service arriving home by 2pm.

I enjoyed the ploughing, harrowing, planting and cultivating and liked to sit on the plough as it was being drawn by the oxen and led by a young African lead boy (the voorlooper) with reins made from ox skin (reims) attached to the heads of the two lead oxen. About midway along the span walked the driver with a whip on a long thin stick. The whip rarely struck an oxen, but the sound kept the oxen pulling their weight. My job ploughing was to steer it with a lever operating the front wheel, so that it was always in the centre of the furrow. At planting time I would sit on the planter behind just two oxen.

A John Deere tractor to replace the three spans of oxen

However, a span of sixteen oxen with three workers pulling a three-disc plough would only turn over a little more than an acre a day and it took six months to complete Pearson’s 600-700 acres of land under cultivation. Tractors were being used more and more, so a second hand John Deere tractor, with iron wheels and steel lugs for traction was purchased with a four-disc plough and I took over responsibility for their operation. Now I was able to plough one acre of land an hour and would be out on the tractor from dawn to dusk, six days a week, for six weeks each year, to complete the ploughing and have the fields all ready for planting as soon as the first rains came. By coupling three planting machines together with a worker on each, we could plant eighty acres of maize daily.

In the 1932 season I had all the lands ready for planting, and when good soaking rains fell, we were ready to plant the maize seed, but the tractor was not pulling well that day, or the next. I was upset because we needed to take advantage of the good planting weather, so during my lunch break knelt beside my bed and prayed, "Lord you know how important it is to get the crops planted during this weather, You also know why the tractor will not start so please help me find out what is wrong as I have tried everything I can think of." On going back to work I noticed a bolt, not easily seen, that had worked loose and caused the ignition timing to slip. Once the timing was reset, planting went at a good pace! When the season was over I completely overhauled the tractor and it was taken apart and cleaned and reassembled.

Headquarters now recognized me as a farm employees and I was paid four pounds a month, until we left in 1934. In that time the maize crop increased from 1,500 bags of 205 lbs each in 1930 to 4,420 bags in 1933, but we left Pearson before the 1934 crop was ready for harvesting. We also grew beans, sun hemp, wheat and pumpkins for sale, our pumpkins being sold by the van load (half a ton) for thirty shillings a load and we also sold eggs.

The maize crop bagged and ready to go to Selby siding. Shelling the maize; about 350 bags were done a day

Locust swarm at Pearson Farm

Locusts were unwelcome visitors from North Africa and would land on a farm and eat anything that was green destroying hundreds of acres of maize. The swarms were seen from miles away as a very large dark cloud three or four miles across. Our workers would beat old tins and light fires, hoping the noise and smoke would keep them away. and making them produce as much smoke as possible. They laid eggs, and once the eggs hatched, young locusts started hopping toward any green crops, poisonous spray was the only way to stop them. After a whole day spraying, I had blisters covering my arms and legs.

Hunting wild pig

Wild pigs could really damage the maize crops and we had six nightguards to protect them. They would beat a plough disk to scare the pigs away, but sometimes took a nap when the pigs would get into the land. I would be out all night at least three or four times a week to make sure the nightguards were awake. When it rained, farmers had to be extra vigilant for wild pigs. Once a year the farmers got together with their farm workers and would set a hillside ablaze and wait for the pigs to flee and be shot. Other times the workers would act as beaters and drive the wild pigs towards us.

At 15 years old, I become an unpaid building contractor

Until then, no Sunday services had been held on Pearson, and there was no church, which was a great concern to my Dad. However, the red brick house which Dad built before the training college had moved to Howard was still there and I suggested to him that we pull it down and use the materials for a place of worship. I said if he would give me one of the farm workers, I would dismantle the house, transport all the materials two miles and erect a hall for the cost of the wages of the worker and cement for the seats and floor. Farm wages at the time were less than one pound a month, plus 45 lbs of maize meal and dried beans and salt.

Jonas and I carefully removed the corrugated iron roof and the roof timber, took out all the doors and windows and frames, and then took down the walls brick by brick. Lime mortar had been originally used, so the bricks came apart quite easily. One night, whilst picking up bricks, I was bitten on a finger by a snake. I picked up a broken piece of glass and slit my finger where I was bitten and headed for home. Dad rubbed some permanganate of potash into the cut – that was the usual remedy for snake bites then and I soon recovered.

The recycled building materials were carted to the proposed hall site, about one hundred yards from our house. We had to make lime for our mortar, fortunately there was soft limestone at the bottom of the hill below the house and although the old limestone operations had ceased twenty years previously, the old kilns were still there. We found enough pieces of lime in the old pits by digging and used one of the old kilns, which we cleaned out, and burnt sufficient lime to build the hall.

It took six months of hard work to demolish the old house and build a place of worship for the farm workers. There was great rejoicing at the opening, it was used every Sunday and often during the week for women’s groups. Neighbouring farm workers also came to worship with us. When my younger brother Andrew was put in charge of the farm at least 25 years later, this building was still their place of worship. Captain Jack Lewis, who succeeded Andrew, built a larger hall and used my building for storage as it was now old and something better was needed to worship in. However it was still standing about 50 years later and may still be.

The Sunday service congregation leaving Pearson Hall that I rebuilt using salvaged bricks. Me ploughing on the John Deere tractor with a four furrow disc plough

A journey to the Victoria Falls

There were slack periods in the farming calendar, we had visited the Niagara Falls in Canada, and my parents wanted to compare them with the Victoria Falls. We took our Model A Ford half ton truck, I was driving with Mum and Dad in the front with me, while Rose, Lily and Andrew were in the back, open to the sun and wind. We travelled all day and at sunset reached Inyati where we slept by the side of the road.

Next day we set out early and drove all day over terrible roads, at one place a forest fire was burning on both sides and in the centre of the strip road, but cars had much higher clearance in those days, so after studying the situation for a moment or two, we just drove through the fire, reaching Wankie (present-day Hwange) just before dark where we camped for the night on the outskirts of the town. Next morning we discovered and drove along 50 miles of the new railway track[xxxi] with gentler grades, no sharp curves and good river crossings as the new track was not yet laid and that made an excellent road!

It had taken us three days to get to the Victoria Falls and what a wonderful sight they were; Niagara Falls just cannot be compared! Here we pitched our tent in the camping grounds and like many others, had our tent raided by the monkeys who stole our sugar whilst we were away sight-seeing! To add insult, the monkey with the sugar bag enjoyed emptying it in a tree above us out of reach!

The following year we drove to Chirundu where a pontoon operated by Jimmy the Greek took cars over the Zambesi river, although they amounted at the time to only two or three a week. The roads were in terrible condition and driving was slow, driving back up the very steep escarpment on the narrow stony track took all the power our vehicle had, but we made it to the top and got back to Charles Clack Institute near Karoi late that night.

Kirby family at Chirundu, Mum, Dad, Rose, in front Lily and Andrew

I become a Salvation Army senior soldier

The corps officers in Salisbury were Major & Mrs Walton, they had been in Sinoia before us and one Sunday morning well over sixty years ago, Major Walton enrolled three of us as senior soldiers and we have each been active Salvationists ever since and still keep in touch with each other. One was Lucy Champken, daughter of the grocer who bought our pumpkins. She was very active in prison ministry and every week visited all the city bars with the Army’s War Cry magazine. The other was Ruth Hawkins, now a retired Brigadier, and great friend.

Training to be a Salvation Army officer

I had felt for some time that God was calling me to become a Salvation Army officer and follow in my parent’s footsteps. In mid-1934 Mum and Dad were due their furlough and I accompanied them on the voyage to England. At the time all the talk in London was about King Edward VIII and Mrs Simpson and whether the King would have to abdicate.[xxxii] Mum’s family were very much involved with the Salvation Army in St Albans and as we stayed with them, I began to be drawn in. My cousin Cath had a good singing voice and every Saturday evening we toured St Alban’s pubs, she sang hymns and I distributed War Cry. Most of the Salvation Army printing was done in the city and there was always a well-attended Saturday evening open meeting.

My parents returned to Rhodesia, but I stayed on hoping to be accepted at the International Training College at Denmark Hill. In the meantime I worked near Southend-on-Sea at the Hadleigh farm where many ‘down and out’ men went for help. There were good orchards, cattle, greenhouses and a market gardening area, it was well known for tomatoes and a truck would leave soon after midnight to get a load up to Covent Garden market. To augment my one pound a week after work I would pick gooseberries for 6d. for a large basket of gooseberries. I also played trombone in the Corps band and we visited other Salvation Army centres, including Alexandra Palace, where we listened to General Eva Booth, and I taught Sunday school. One of the lads was Bill Rivers who eventually became private secretary to General Brown.

International Training College at Denmark Hill

On 15 August 1935 I said goodbye to Hadleigh and made my way to Denmark Hill to start training along with over 400 others (300 women and 110 men) of the Liberators Session. Then men and women were not even allowed to speak to each other with separate dining rooms and classes and at united events in the central lecture hall we sat on different sides using separate entrances. Initially, I felt very shy with my lack of education. We did field training in Chelsea, Catford and Wandsworth and even Guernsey. I had a dose of malaria, but a doctor cadet, Edgar Stephens, recognised the symptoms and got me quinine.

Early in 1936 was the Self Denial Appeal and I spent 3 weeks walking from door to door in Thornton Heath, a poor area and most donations were a penny and thruppence, sixpence was a rarity. It was not a rewarding experience going from door to door for eight hours a day, six days a week, and I only raised about thirty pounds.

Finally, on 11 May 1936 we found ourselves at the Royal Albert Hall with a dedication service and then a cadet pageant, followed by General Eva Booth’s speech, before we were commissioned as Salvation Army officers. Imagine my surprise when I returned to the Training College and there on my dresser was a boat ticket to Cape Town and details of my travel arrangements.

Return to Africa and the Howard Institute

Six of us fellow officers travelled together on the Dunluce Castle for Cape Town for Rhodesia. They were Ivy Archer, Bram Davis, Horace Fitzjohn, Bill Lewis, Mrs Sercombe, and myself. The fare was sixteen pounds and took a month, stopping at Tenerife Island, Ascension Island, and St Helena.

I arrived at the Howard Institute in July 1936, about 3 weeks before my 21st birthday, to take up my post as the assistant industrial officer. The Institute now had a primary boarding school for boys and girls, although boys outnumbered girls 4:1, as most African parents at the time thought educating girls a waste of money with so few career opportunities, and a Teacher Training School; together they had 250 students. The Salvation Army Officers Training College has 30 cadets in training. There were African teachers and Salvation Army officers on Howard Institute to carry out this educational programme at that time.

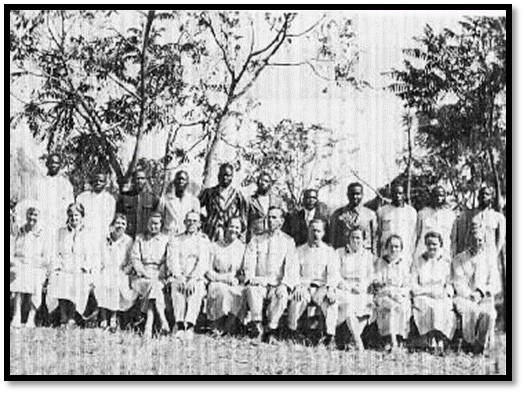

The entire teaching staff at Howard Institute in 1936

The staff included Adjutant and Mrs Tabor (Principal) Adjutant and Mrs Erikson (Assistant Principal and Industrial Officer) Captain and Mrs Lewis (Headmaster) Adjutant Doris Dolman (Teacher) Captain Marie Anderson (Teacher Training College) Captain Mary Stevens (Domestic Science Teacher) Captain Wilkinson (Nurse) Captain Margaretta Nelson (Teacher Training College) who was Canadian.

I was Adjutant Erikson’s assistant and he was responsible for all the boys’ Industrial work, consisting of woodwork, building and agriculture, which included a forest station and vegetable gardening. He was also in charge of all the repairs and the water and electrical systems at Howard.

The school day consisted of half the students in academic classes in the morning, the other half did industrial or general work, then after lunch they changed over. Every student, when not in the academic classes, would be involved in either industrial classes or general work. The latter was necessary to keep Howard clean and tidy, cook meals, and carry out building and repairs which were not undertaken as class projects. The building, woodwork and agricultural classes consisted of both theory and practical work and were examination subjects. Each week, on each subject, one hour was theory and six hours were practical work. Four or five hours a week was spent on general work including agriculture, tree planting and vegetable gardening.

I enjoyed the practical work, but being in a classroom in front of a class teaching theory for an hour which took a good deal of study and preparation time, especially when the Government industrial inspector paid his annual visit to the school and sat in on a class. Still I enjoyed my work and was happy at Howard. As I was teaching agriculture to the senior class, I did a correspondence course in Agriculture Science. We did some theory in the classroom when the students made notes followed by practical demonstrations. On a one acre demonstration plot they were taught ploughing, soil preparation, crop rotation, manuring, green manure crops, planting, crop diseases, pests, harvesting, and marketing and we grew useful food for the kitchen.

NAZ: Homecraft class and women Cadets at Howard Institute, late 1930’s

After a year my supervisor Adjutant Erikson was transferred, and I took over, assisted by three African teachers and a general worker. Any repairs to the water pump and lighting generator were my responsibility. We had a deep borehole and if something went wrong I might work through the night to get the repairs done as the water storage tank only held a day’s supply.

Transport was also my responsibility; we had a van and a 3 ton truck which carried six or seven people for shopping trips to Salisbury and I did about 50% of the weekly runs. Our clinic often had outpatients brought in on a scotch cart (a two wheeled ox drawn cart) or on a sleigh. Other times, a patient in a distant village was too ill and I would take Captain Wilkinson to their kraal and bring them back to the clinic. .

In 1937 Lieut. Bill Lewis joined me to assist with the industrial work taking over woodwork classes and helping with the power lines, lighting and electrical repairs which reduced my load considerably. We shared a house and one of the domestic science girls did our washing, ironing, cleaning and generally kept our house and we had our lunch with Captains Stevens and Nelson. This was a great help to us and we really appreciated their kindness.

Our industrial theory classes were generally held outside under a tree, or in a workshop if it rained, and when finally permission came to build a classroom I drew up plans for three classrooms, an office and storeroom with granite blocks for the front and concrete blocks for the remaining other walls. Dressing the rocks with hammer and chisel was very slow, so a miner friend showed me how they could be blasted and we purchased dynamite, detonators and fuse. The building class drilled holes in the larger rocks and after packing them with dynamite I would light the fuses and run for my life. This way we soon had enough dressed stone for the front wall and the granite chips were used in the concrete blocks. Lady Stanley[xxxiii] agreed to lay the foundation stone when the walls were three feet high and when building was complete the Chief Native Commissioner for Rhodesia, Mr C.W. Bullock, performed the opening ceremony.

The roads in the Chiweshe Reserve around Howard were not very good, especially in the rainy season when they became extremely muddy, and often the vehicle was pulled through the first two or three miles by oxen to where the road had a more solid base. One Salisbury trip when I was driver we managed to get through the soft part within the Reserve and onto the farm road to Glendale, so I thought that our troubles were over, until we came to a flooded culvert. We proceeded cautiously, but the water was a bit deeper than I expected, the spark plugs became wet causing the engine to stall, and before the engine could be restarted, we were flooded. Everyone got out and waded through the water to dry land. The rain stopped, but the electrics would not dry out for ages. When finally it started it ran on only two cylinders until it warmed up and then we continued much to everyone's relief. That night I stayed with Ruth Hawkins at her mother’s boarding house and she had dried my clothes by morning.

Staff pushing the Howard truck to restart it

Sport at Howard

Our principal, Adjutant Tabor, was keen on sport and our staff football team played the Howard first team each week. We were evenly matched, I played goalkeeper for the staff team. We played other missions, as well as the BSAP and Salisbury teams. We also had an annual sports day when the houses competed with each other and the winners represented Howard against the Waddilove Training Institute team in Marandellas (present-day Marondera)

Religious services at Howard

We had our regular Sunday services and each officer took turns in conducting them. Every morning the whole school attended prayers before commencing the day and Saturday evening was the staff spiritual meeting. One week it would be the entire staff, the next we missionaries met by ourselves in the principal’s house. This was a gathering when we could share our problems, anxieties and pray for each other followed by a Bible message and we each took turns conducting these meetings.

Boarding master

The chief duty as a boarding master was for the food purchases and keeping an eye on the cooks. Complaints about the food were common. One day, the whole school refused to eat their meal and went on strike demanding different food. When this was not given to them they marched to the top of a hill just off our property and sang `Bread of Heaven, feed me till I want no more.' The territorial commander was there that day on business, but he was not in the least perturbed and laughed at them. I climbed up to them, and after a while they returned and we had no further problems.

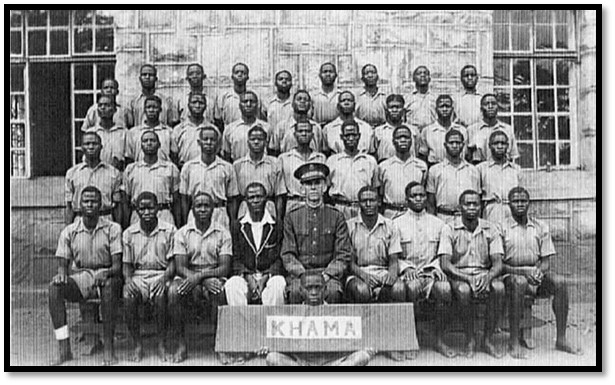

Khama boarding house with housemaster and principal

The same thing happened at the Bradley Institute, a Salvation Army boarding school for boys, at Madziwa, north of Shamva and we had a rather desperate phone call from Major Emmie Richards, the principal, who could get nowhere with them. So I went and spoke to the students who were soon persuaded to return to their classes.

Nurse training at Howard

In January 1939 the government medical department gave permission to train nurses at Howard, the first two were Rebecca Kudzai and Eva Hlabangana. Captain Wilkinson, our Howard nurse, was transferred and was replaced by Captain Coleman from England. In February we learnt a Canadian nurse would be staying at Howard for three months for acclimatisation before going to Ibwe Munyama Clinic in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) which was extremely isolated.

Student nurses in training with the Principal and Mrs Tabor, Captain Stevens and her staff

I first meet my future wife Adjutant Isabel Sloman

When the time came Major Tabor collected the officer at Salisbury and phoned me from Glendale, our usual procedure in the rainy season. I took a span of oxen to where the road was very sticky on Mr Butler's farm. But before I arrived, the van sank so far into a muddy spot that the battery, which in those vehicles was placed under the floor boards, was ripped right out of the van and smashed. Mr Butler brought a truck with his workers, and after pushing the van out, it was towed for a couple of miles. Then they spotted me with the oxen. Major Tabor turned to me and said "Lieutenant Kirby, I want to introduce you to the new missionary officer, Adjutant Isabel Sloman." Then I was in the mud hooking a chain from the van’s front axle of the van to the oxen and pulling them to the principal's house.

Adjutant Isabel Sloman arriving at Howard in March 1939

Isabel came from an active Salvationist family, both parents encouraged her own participation from an early age. She did officer training and was commissioned in 1928 and as a registered nurse in 1931, volunteering for missionary work in Africa and being promoted to Adjutant.

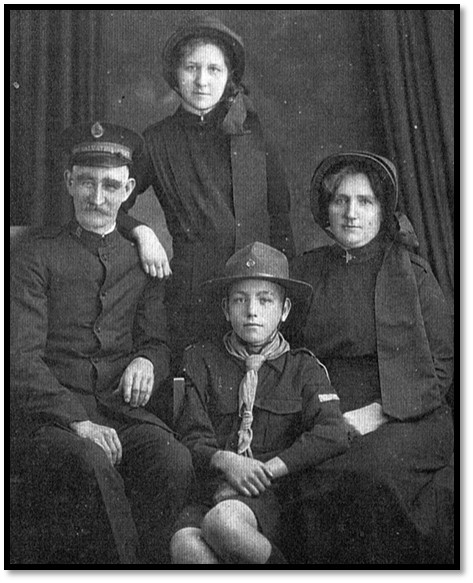

Mr & Mrs Sloman with Isabel and Norton

One day I received news from a worker that our nurse had fallen off her bicycle and was sitting in a mud puddle. I investigated, it was hard not to have a good laugh at the sight of her sitting there in her nice white nurse’s uniform. She had been going quite fast and on the slippery road went into a skid and over the handlebars. I helped her onto the grass verge, collected the van and took her home.

She was so competent that Major Tabor asked if she could stay permanently and her transfer to Ibwe Munyama was cancelled. She began a formal nurse training course for our two recruits, using her own lecture notes, and at the end of the first year added two more recruits, Rhoda and Marty.