Patrick Campbell, husband of Mrs Patrick Campbell who went to Mashonaland and was killed in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

Patrick Campbell, husband of Mrs Patrick Campbell who went to Mashonaland and was killed in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

Patrick Campbell (1863 – 5 April 1900) is best known as the husband of Mrs Patrick Campbell (9 February 1865 – 9 April 1940), born Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner and known informally as "Mrs Pat" who was an English stage actress, best known for appearing in plays by Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen. She also toured the United States and appeared briefly in films.

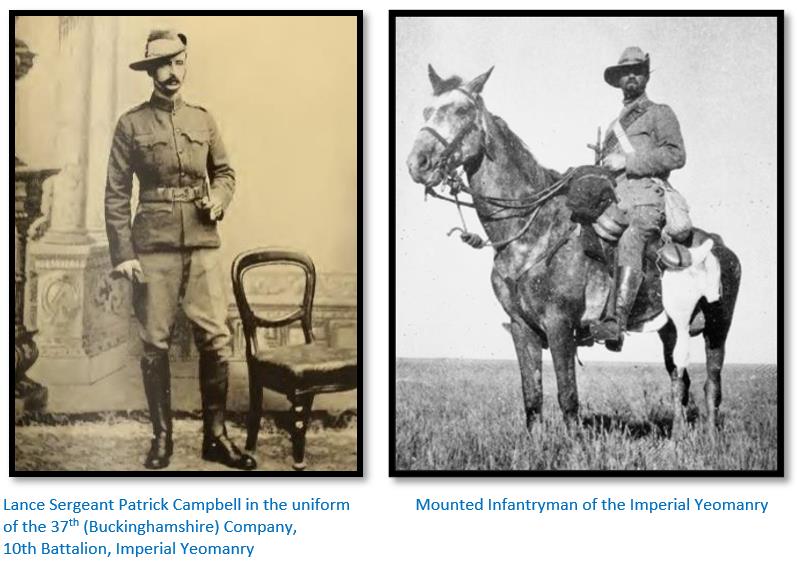

In 1884 she eloped with Patrick Campbell, while pregnant with their child, Alan "Beo" Urquhart and their second child, Stella, was born in 1886. Some articles then state they separated or estranged. However in her book ‘My Life and some Letters’ she writes that Patrick's health was not good and in 1887 he was ordered by his doctor to take a sea voyage for his health, although in his photo in the uniform, taken at the start of the 1899-1902 Anglo-Boer War, he looks fit and strong.

He was to stay away from England for six and a half years in Australia, South Africa and then Mashonaland from 1887 – 1892. He found employment, but never enough for Beatrice and the children to live on. Fortunately she carved out her own career.

Travels to Australia, Mauritius and then South Africa

Patrick left England in October 1887 for Australia and was working in Brisbane by December for £2 a week.[i] Initially he had journeyed to the Far East in search of better prospects, but by July 1888 he was in Mauritius waiting for a ship to South Africa being most probably attracted by news of the fortunes being made on the diamond fields. Patrick writes from Mauritius on the 28 July 1888: “I do hope Kimberley will be the end of our troubles.”[ii]

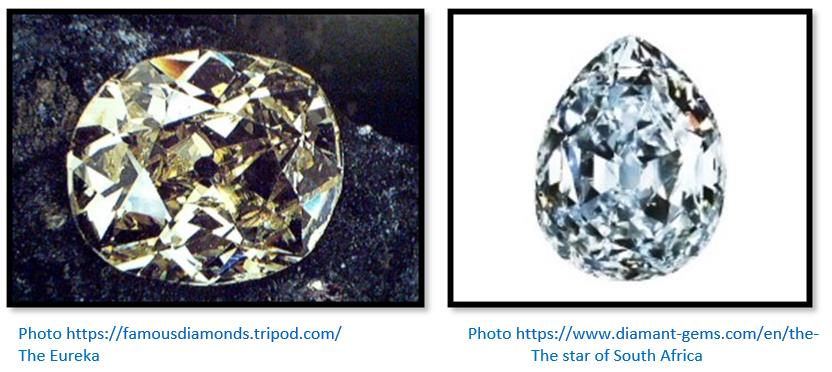

The discovery of 21.25 carat diamond[iii] occurred in early 1867 on the land of a poor Boer farmer, Daniel Jacobs, near the small, isolated settlement of Hopetown on the Orange River in the Cape of Good Hope Colony.[iv] His son, Erasmus Jacobs, collected ‘blink klippe’ (bright stones) on the south bank of the Orange river and his confirmed find prompted local Boer families to look more carefully for similar stones.

Additional diamond discoveries prompted news of the finds to spread and small parties of prospectors began to arrive. By 1869 hundreds of carats had been found including the 83.5 carat stone known as the ‘Star of South Africa.’[v] By 1870 diamonds had been found on the Bultfontein farm - 20 miles southeast of the Orange river diggings - in what came to be called the “dry diggings” - that were later recognised as occurring in the upper weathered and decomposed sections of a volcanic pipe.

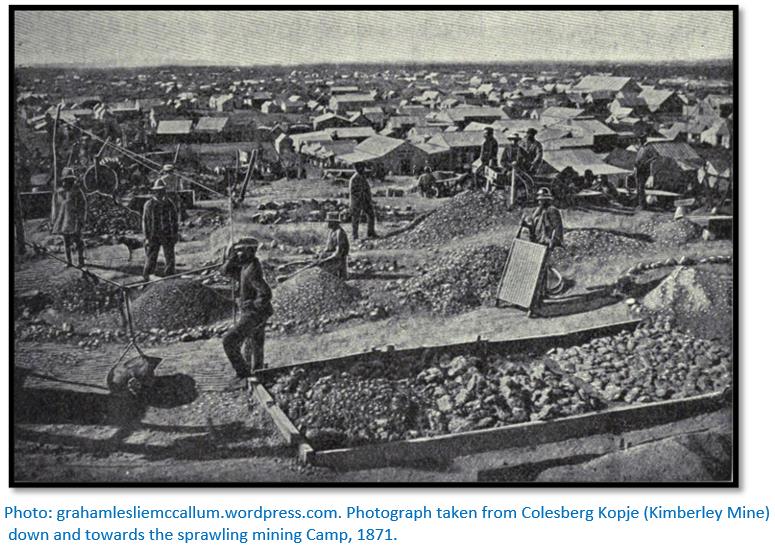

These events started a rush of thousands of people from all around the world to explore for diamonds and dream of making a rich discovery. Over a large area of the Cape Colony, and within two decades, many rich deposits were found that would later become the famous diamond mines of South Africa with the annual export of rough diamonds from South Africa rising from 200 carats in 1867-1868 to approximately 3.8 million carats by 1888.[vi]

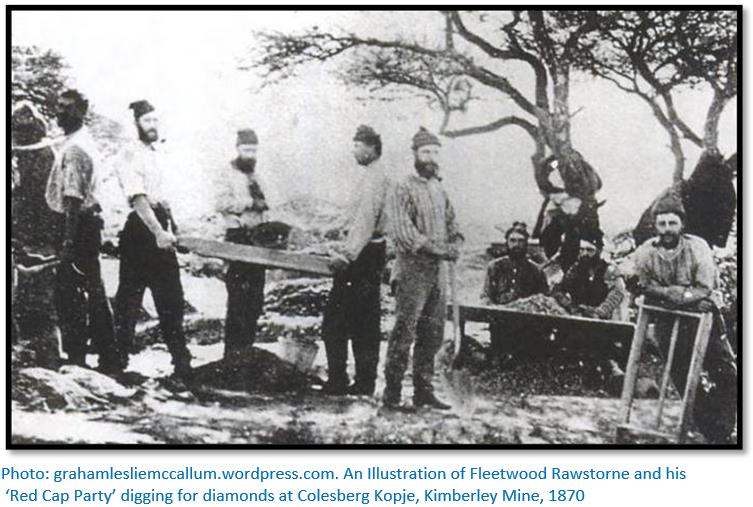

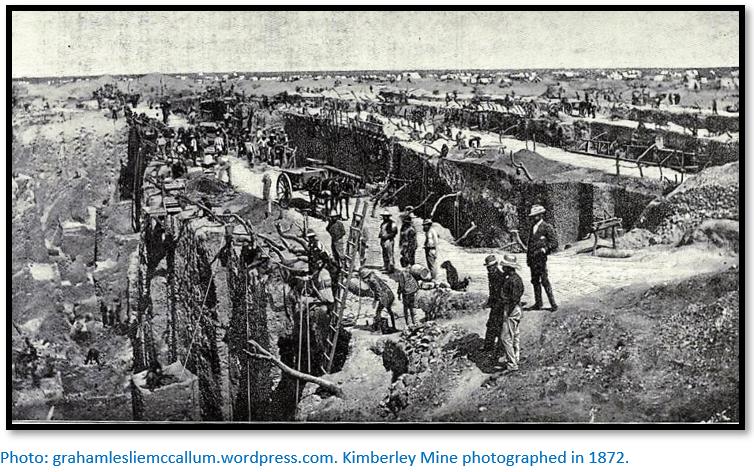

The first diamonds at Kimberley were found by Alyrick Braswell on Colesberg kopje by members of the ‘Red Cap Party’ at Vooruitzigt Farm, which belonged to the De Beers brothers in 1871. The ensuing scramble for claims led to the place being called New Rush and by 1872, one year after digging started, the population of the camp of diggers grew to around 50,000.

However the diggings of the numerous small claims made operations increasingly dangerous and wasteful and on 13 March 1888 the leaders of the various mines decided to amalgamate the separate diggings into one big mine known as De Beers Consolidated Mines Limited. [vii]

Patrick Campbell’s connection with the 1890 occupation of Mashonaland

By September 1888 he was working for Kimberley Central Diamond Mining Company (KCDM) at £300 per annum as a clerk and in November he was busy putting together a diamond display for the forthcoming Paris Exhibition. His letter of 17 September 1888 states that Kimberley: “…seems a splendid place for making money. I get £300 a year to start. My predecessor who was only five months with the company [KCDM] and then lost the post through drink, got a rise of £50 at the end of three months. I do hope I get the same…”[viii]

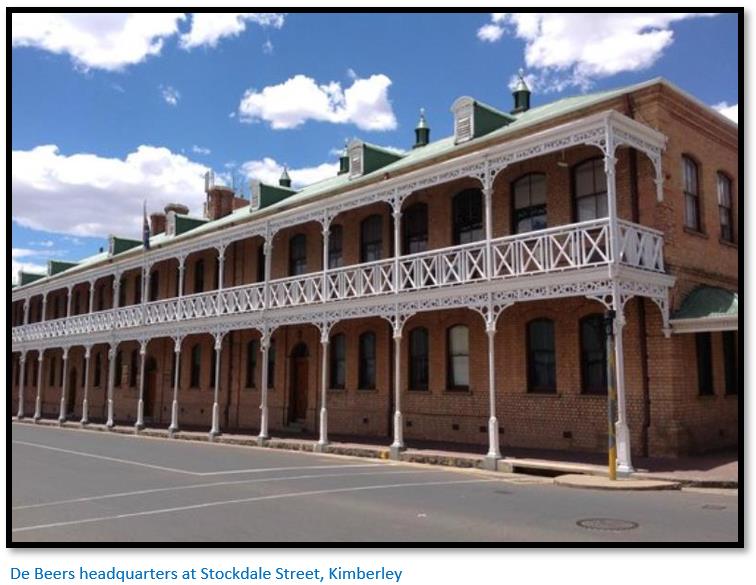

KCDM was owned by the Barnato brothers and had merged with other diamond mining companies to challenge Rhodes’ De Beers Mining Company, but in 1888 was bought out by De Beers. Patrick was working at the Barnato’s Stockdale Street offices – now the De Beers Consolidated Mines Head Office.

But slowly his views ware changing and in January 1889 he writes to his wife that: “I am beginning to hate Kimberley; what I want is for Rhodes to send me up into the interior to Lobengula’s country, Matabeleland. The general impression here is that the first fellows to get sent up will make their fortunes. I shall do my level best to get sent.”

In early September 1889 he was still working for KCDM but feeling increasingly despondent and trying to get involved with the expedition that was being talked about to Mashonaland.

Selected as one of the ‘Twelve Apostles’

His efforts to join the Mashonaland expedition were successful and during this period he must have met Cecil Rhodes and been selected to become one of the ‘Twelve Apostles.’ He resigned from KCDM by early October and by 8 November 1889 was writing to tell his wife he was on his way to Mashonaland. “There are 15 of us going, all connected with the De Beers Company, and mostly friends of Rhodes. We are sworn in and attached to E Troop Bechuanaland Border Police, with Troopers pay, about £5 a month (and all found) Rhodes and all the Directors tell me to go, and I shall never regret it. Everybody here seems to think we are bound to make our fortunes as we are being sent up by Mr Rhodes, who is a sort of king out here.”[ix]

Campbell begins military training with the Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP)

Frank Johnson writes in Great Days that they were the sons of prominent citizens who had persuaded Rhodes to take them into the Pioneer Corps and alleges he said to Rhodes: “If you insist on increasing the numbers, you must pay for them and Rhodes did.”[x]

The truth is probably different. After the Royal Charter was signed in October 1889 Rhodes knew the British South Africa Company (BSA Company) would need good people to administer Mashonaland once it was occupied. Twelve young men were recruited in November, including Patrick Campbell. Rhodes knew they would need a military escort – this is before Frank Johnson and the concept of the Pioneer Column – so why not let them join the Bechuanaland Border Police? (BPP)

The BPP was in existence already as a military / police force. He approached Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa (1889-1895) a keen supporter of Rhodes and suggested the BBP raise an additional Troop of 100 men as escort for the civilian administrators. Their training and administration would take place under the BBP and afterwards the BSA Company would employ them. Loch persuaded the Colonial Office to accept and the ‘twelve Apostles’ were attested into the BBP in early November 1889 on a ‘temporary basis.’[xi]

Rhodes’ Apostles

Patrick worked at the Kimberley Central Diamond Mining Company until it merged with De Beers when he was selected by Rhodes as one of his ‘Twelve Apostles’ and attached to the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) for military training in November 1889.

Then on 1 April 1890 he joined the newly-formed BSA Company Police as Trooper No 483[xii]

even before the Pioneer Corps had started assembling at Camp Cecil in Bechuanaland. It was only on 26 May that Frank Johnson arrived at Camp Cecil to take charge from Maurice Heany. Training of the Pioneer Corps took place throughout June, they were inspected by Major-General Methuen[xiii] on 24 June and arrived at the Shashi river on 1 July 1890 to start building Fort Tuli.

On 13 July 1890 he was discharged from the BSA Company Police along with the other ‘Twelve Disciples’ and transferred next day into the Pioneer Corps as No 163. Robert Cary (The Pioneer Corps) writes he was initially a Trooper in B Troop before transferring three days later to A Troop.

Skipper Hoste supplied their names after they joined the Pioneer Column: “The Pioneer Column had also a slight addition to its numbers in the ‘Twelve Apostles’ though as a matter of fact there were thirteen of them. They were thirteen young fellows selected by Rhodes himself at Kimberly. They were supposed to act as the Administrator’s bodyguard, but as the Administrator had not yet taken over his job, a bodyguard would be no use to him. Heany and I therefore divided them up between us. Their names were F.W. Adcock, P.W. Campbell, T.J. Christison, A. Eliot, W.L. Cornwall, R.T. Coryndon, W.D. Durell, F. Ehlert, H.W. Featherstonehaugh, J. Grimmer, J.M. McRobert, B.E.A. O’Meara and W.K. Steir. On our arrival at our destination [Mt Hampden, later changed to Salisbury, the site of present-day Harare] the first civil servants were selected from them.”[xiv]

Pioneer Column accompanied by the BSA Company Police march to Mashonaland

B Troop of the Pioneer Corps crossed the Shashi river on the 10 – 11 July 1890 and began building the wagon track to the north-east. Rhodes’ ‘Apostles’ joined the Pioneer Corps on 13 July, the day they left the BSA Company Police. Initially transferred to B Troop, three days later he was transferred into A Troop. The main body caught up with B Troop on 18 July at the Tshabezi river and next day A Troop took over road-building operations.

A Troop continued with roadbuilding until the Lundi river was crossed and from 5 August until the Providential Pass had been climbed on the 14 August B Troop carried out the roadbuilding. The march resumed from Victoria on 19 August with B Troop in the lead and this continued until Fort Charter was reached on 4 September. A troop then led the way towards Mt Hampden until the site of Salisbury (now Harare) was reached on 12 September 1890.

At Salisbury (now Harare) as part of the British South Africa Company administration

After the Pioneer Column arrived at Salisbury on 12 September 1890 where he began service as A.R. Colquhoun’s (the Administrator) clerk at Salisbury in 1890-91. Hickman says he rode with despatches for Rhodes from Salisbury to Macloutsie (490 miles / 790 km) in 8 days using horses from the post-stations and after a day’s rest at Macloutsie rode onto Palapye, a further 120 miles (190 km) on two fresh horses.[xv] One of them was “Alley Sloper” who Cpl Divine wrote in his memoirs: “He (Patrick) also carried a chit from the OC Forces. Instructing all OC’s of Troops to let him have the two best horses in any Troop. To my regret, my horse and that of the senior sergeant were chosen, so I lost ‘Alley’ and never saw him again.”[xvi]

Patrick Campbell’s letters to his wife Beatrice (Mrs Pat) from Mashonaland

In a letter dated 7 January 1891 Patrick describes the above event: “Soon after writing to you I started with Mr Colquhoun for Manica, went down with him to Mutassa [Mutasa] where he got the treaty with the Manica King, over which so much fuss has been made in the papers. He then sent me post haste by myself to ride to Fort Charter, a distance of 120 miles as the crow flies, through dense bush, over many mountains and across several large rivers – to take a message, reporting the getting of the treaty, to be forwarded to Mr Rhodes in Kimberley. I then had to return immediately and meet him at the kraal of a chief named Gotos [Gutu] some 80 miles away from Mutassa. This I did and was at once sent away by himself with a Bamangwato boy to go to Mutassa and remain as the company’s representative until Mr Colquhoun sent someone to relieve me…Mr Colquhoun then sent me off to report verbally to Mr Rhodes, who had started on a tour through Bechuanaland with the Governor, as to the proceedings of the Manica mission. In eleven days, I rode a distance of 600 miles to Palapye, the chief Mangwato town, where I met Mr Rhodes and the Governor, Sir Henry Loch.“ [xvii]

The first member of the Pioneer Corps to return to Kimberley

Patrick continues: “Mr Rhodes was very kind and very pleased to see me, the first member of the Pioneer Expedition who had come down.” He was then sent down to Kimberley by post cart travelling night and day to report to the BSA Company secretary, Dr Rutherfoord Harris. He states that as the first Pioneer down from Mashonaland he did not have half an hour to himself the entire week being interviewed by newspapers, at the office all day giving information and feted with dinners at night. “Sickening, I can tell you, darling, after the grand free, healthy open-air life I had been leading so long.”

Hopes to make his fortune but has no money to send his family

“I have a splendid chance of making a large sum of money in a little time. We, that is, Mr Colquhoun’s staff, have sent out two splendid prospectors, fully equipped to peg out and develop our claims. They have gone out under the wing of Mr Selous, who is taking them to a very rich district only known to himself and Mauch, the German geologist and explorer, and not discovered as yet by the prospectors who came up with us. Splendid reports are coming in from all around about the gold prospects.”

“What a brute I am to leave you all alone to fight so hard a battle at home. And now I am afraid that most, if not all, the money due to me for the last six months has been paid towards my share of the expenses of our prospecting party. I have no time to find out before this mail goes out but will see what I can do next mail. I only get £15 a month now and rations. The company will not pay high salaries at first; they promise that in a few months they shall be increased materially…This is a wonderful country. Goodbye my own. Yours for ever, Pat.”

A cheery letter from Salisbury dated 22 March 1891

They have been shut off from all postal services for three months with flooded rivers: “the last news we had from Kimberley was dated 18th December. I sent a cheque for £30 to a friend of mine at Kimberley, Harold Ingall, on 9th January, asking him to send you a draft on London for proceeds, and I pray God it has reached you…I will send you some more money as soon as communications are opened.

This letter is being taken right across Matabeleland to Bulawayo with some despatches from the Administrator to try and get communication that way. The man who is bearing them is a Mr Usher,[xviii] who has just come through from Bulawayo, leaving there on the 12th February, bringing some cattle which were purchased from Lobengula for rations and which we are very glad to see. I can tell you, as we are, owing to the road being closed, completely out of food, and have been living on what we could get from the natives – principally Indian corn, rice and pumpkins – for some time.

Usher brings some good news from Bulawayo, the capital of the Matabele, he was present at the ‘Big Dance of the Nation’[xix] when all war movements of the year are arranged and although several of the Chiefs asked the King to be allowed to march their impis against us here in Mashonaland, he resolutely refused to allow them, saying that he was well pleased with what the English had done and he would not allow them to be interfered with. We have also letters from Mr Moffat,[xx] the British Resident at Bulawayo, to the same effect.”

And now darling, I have the commencement of some good news for you. I told you in a previous letter that we had formed a syndicate for pegging out the claims we get as pioneers and had engaged two first-rate prospectors named Arndt and Arnold.[xxi] Well, we had a letter the other day from Arndt to the effect that he had discovered the ‘Kaiser Wilhelm’ goldfields,[xxii] which have been so much talked about all over the world and which have only be seen by a few white men before, amongst them Mauch, the German geologist,[xxiii] who was most enthusiastic about their richness. So far as we can understand from Arndt’s letter, brought in by a native, the fields lie about 100 or 120 miles to the north-east of this place and are of very large extent and Arndt says that having only just seen the fields, he did not like to say much, but he considered that they were of the finest formation that he had ever seen in his experience of over 20 years prospecting.

So dear, this is very encouraging news and everybody here is congratulating us and saying we are sure to make our fortunes, as owing to the difficulties of travelling, the rush which at once took place on receipt of the news of the finding of the goldfields cannot possibly get there for two or three weeks and our men will have the fields a good six weeks to themselves and be able to take the pick of the reefs.”

Sweetheart, I pray God I shall be able to make a lot of money to be able to come home and make you comfortable and give you all the pleasures that I long to, to repay you for all the misery and discomfort I have put you to…”

Heyman’s fight with the Portuguese at Macequece (Massi Kessi)

Patrick’s letter of 3rd June 1891 describes the battle: “I told you in our last letter of our fight with the Portuguese. I have since had further particulars. We only had 47 men and a seven-pounder and they had 100 Europeans and 300 black soldiers. We, of course, had the best position and, strange to say, did not have a man wounded. They lost two officers and 13 white men and about 50 black. We took nine quick-firing guns from them; they only managed to take two away with them…

Some of our men had wonderful escapes, they had to go out and cut down trees under a heavy fire to get the gun into action. One man had his axe knocked out of his hand by a bullet, another, Tulloch,[xxiv] was chopping down a tree and the bullets knocked splinters out of it. Young Morier,[xxv] a friend of mine, son of Sir R. Morier, the Russian Ambassador, was leaning his rifle against a tree to take aim, when a bullet struck the tree, knocking a large splinter into his face and giving him a bad black eye. A bullet went through the limber of the big gun while they were all standing around working it and entered a cartridge, but fortunately did not explode it.

The Portuguese used the new magazine rifle which shoots splendidly. They were thoroughly beaten – although the fight only lasted two hours and their officers behaved very well – and cleared off pell-mell during the night, leaving the nine big guns behind them. They may come on again, but it will be some time before they can move as the natives are afraid to carry for them.

One of our prospectors has pegged out fifteen good claims, the first start for my fortune, darling. I hope they will turn out good. The fighting, etc, is keeping the country back fearfully…”

Prospects of a quick fortune have faded away

In late 1891 Patrick then set up as a broker in Salisbury with W.L. Cornwall, also another of Rhodes’ “Twelve Disciples” (Pioneer Corps No 163) and Herbert John Morris (Pioneer Corps No 63) Cornwall was appointed Registrar of mining claims for the BSA Company, but was in business by July 1891 as ‘W.L. Cornwall, Secretarial Agent, Auctioneer and Sworn Appraiser’ in partnership with Morris and Patrick Campbell. The partnership was dissolved in September 1895, by which time only Cornwall and Morris were still in Mashonaland.

Robert Cary writes that Campbell proposed the toast to ‘The Army and Navy’ at the first Pioneer dinner at Salisbury on 12 September 1891.[xxvi]

In her book My Life and Some Letters Beatrice writes: “Then Pat went on to Mashonaland, sometimes prospecting with hopes of concessions and settlements and later I heard of his big-game shooting with Selous. How he must have loved that. Then followed many weeks and no letters and Pat could only send money very irregularly. So at last it was decided that I should take up the stage professionally and I wrote asking for Pat’s permission. This he gave and I started my career…”[xxvii]

But once more Patrick’s views had changed, on 6 September 1893 he wrote “I long to leave Africa, where I have had nothing but bad luck.” He was back in England by early 1894, his wife now a successful professional actress using the name Mrs Patrick Campbell. But he was ill from the after-effects of malaria and struggled with his health. His wife said: "When Pat arrived I saw in his eyes that youth, with all the belief and faith had gone: his health and energies were undermined by fever, failure, and the most bitter disappointments. Nothing had come of his hard work, his hopes and his sacrifice. The expression in his face wrung my heart, but the old gentleness and tenderness were there – he still loved me. His pride in his beautiful children and in my success – that was my reward."[xxviii]

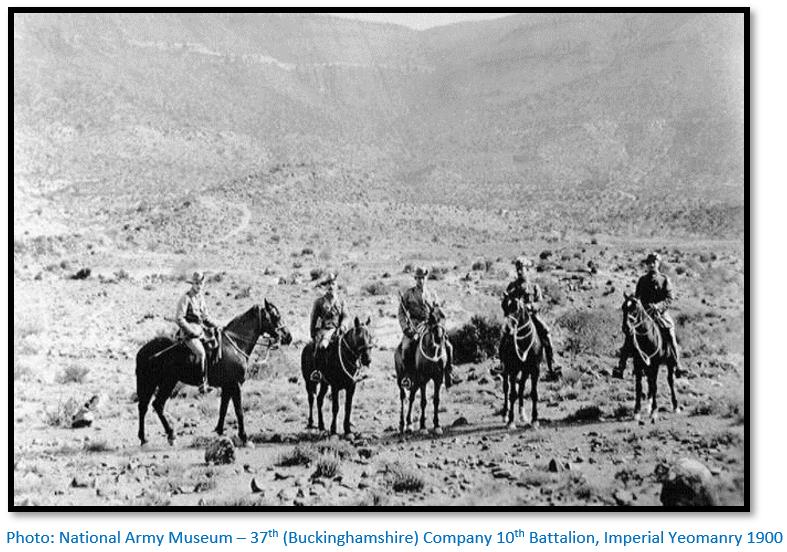

Patrick volunteers in the 37th (Buckinghamshire) Company, 10th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry

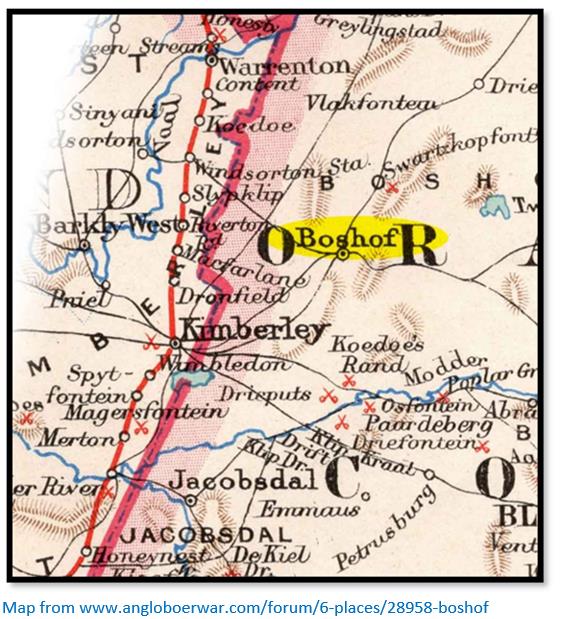

He volunteered at the start of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and joined the 10th Imperial Yeomanry under Lord Chesham and was appointed as No 4810 with the rank of Lance Sergeant. The unit arrived in Kimberley in mid-March 1900 and was with Lord Methuen when he advanced and encamped at Boshof in early April. His death on 5 April 1900 means he served for less than a month on active service.

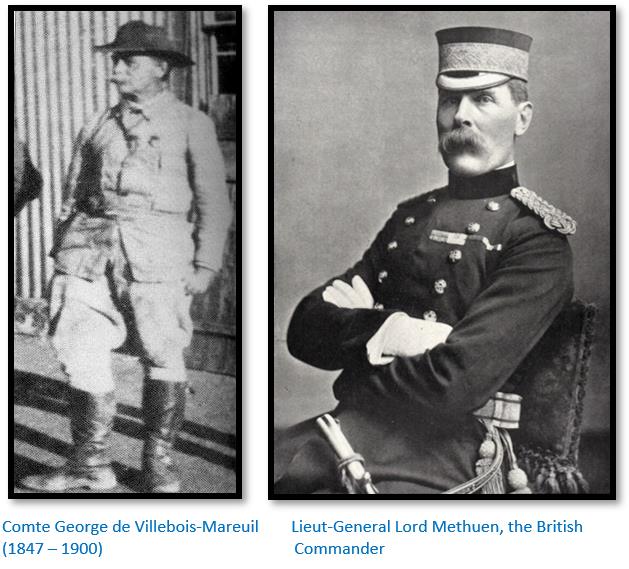

The Boers appoint De Villebois-Mareuil to command their Foreign Legion

Earlier in 1900 Colonel George De Villebois-Mareuil had arrived in South Africa. He travelled to Natal where heavy fighting was taking place and volunteered his services, but neither Piet Joubert, nor General Piet Cronje, paid attention to his advice, or gave his military skills and experience any recognition. However he attended a meeting of the Boer War Council on 17 March 1900 at Kroonstad, the new capital of the Free State after the fall of Bloemfontein.[xxix] President Kruger requested he take the seat next to him and to his own surprise, De Villebois was appointed commander of the Foreign Legion with the rank of vechtgeneraal (combat general) Those serving under him were from France, Holland, Germany, Ireland, America, Italy, Scandinavia and even a number of South Africans.

The battle of Boshof (also known as Tweefontein) on Karreepan farm

Comte De Villebois-Mareuil was critical of the Boers discipline and fighting methods and advocated guerrilla tactics against the British forces in the Orange Free State. A night attack on Boshof would show the effectiveness of ‘hit and run’ tactics.[xxx]

The railway line between the Cape and Kimberley was vitally important to the British military operations, but in order to carry out his first task De Villebois needed horses and supplies. These were available at Hoopstad but enroute the town of Boshof was occupied by a small British garrison that De Villebois decided would be a good opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of guerrilla tactics with a diversionary attack.

On 3 April 1900 De Villebois’ commando of 125 men arrived at Leeukop, 25 kilometres north of Boshof where they liaised with a small Boer patrol of commandos from Bloemfontein, Boshof and Hoopstad under Field-Cornet Daniels. Daniels was given the task of encircling Boshof and cutting the telephone line to Kimberley, while De Villebois and his force would attack the town from the east.

Then Daniels received information from his scouts that Lord Methuen and a force of the 3rd and 10th battalions of the Imperial Yeomanry were marching on Boshof with 7,000 soldiers and 12 field guns[xxxi] and told De Villebois that the attack on the town should be called off.

De Villebois refused to abandon the attack and approached the town from the south-east camping the night of 4 April 1900 on the farm Tweefontein, 8 km outside the town. However his force had been spotted by Methuen’s mounted scouts approaching Boshof. At first light on 5 April six companies of infantry, many of them Imperial Yeomanry, a battery of field guns and the Kimberley Mounted Volunteers were sent to locate De Villebois’ force.

De Villebois’ force reached the farm of Lewis Beck, a merchant at Merriesfontein. He told them it was impossible for the Boer force to stay on his farm as British patrols scouted the area daily.

Miserable and exhausted, the approximately remaining 125 Boers and French, German, Dutch and Irish volunteers moved onto Karreepan farm, the owner Hendrik Groenewald, was then being held in Kimberley prison. The men rested in a grove of trees while the horses were set free to graze. In the meantime Lewis Beck travelled from Merriesfontein to Boshof and by mid-morning Methuen knew exactly where De Villebois and his force were located, although in his official report, Methuen claimed the information was from local Africans.

Two Boer women – Mrs Ryneveld and Miss Enslin[xxxii] - sensed trouble after overhearing two Africans talking to the store owner and hurried off to warn De Villebois’ forces at Karreepan farm. They were stopped by a British patrol on their way and watched the battle from close to a Maxim gun position.

Methuen’s force found De Villebois’ men on two small kopjes. The 25 or so Boers holding one of the kopjes retreated at once and Methuen’s forces carried out a flanking movement to intercept them. The 100 remaining foreign fighters took up defensive positions on a kopje 700 metres to the north west from which the British launched their attack which was supported by field guns and Maxims. [xxxiii]

Some of the Imperial Yeomanry dismounted once they came under fire, requiring an advance of about 1,000 yards in the open. Others rode around the flank of the kopje and then dismounted. Quartermaster Sergeant W.A. Gough of Buckingham with 37th Company recorded: “My first impression of being under fire was that you don’t realise they are shooting at you until you see someone roll over alongside you.”[xxxiv]

A fierce battle broke out and De Villebois’ force eventually suffered thirteen dead and eleven wounded.[xxxv] Although some wanted to surrender arguing they were facing larger numbers and artillery, their commander decided to keep fighting in the hope a looming thunderstorm would allow them to escape. As the British prepared to charge, a Boer showed a white flag of surrender. When the British came forward to take prisoners, other Boers fired into them killing Lieutenant Arthur Williams.[xxxvi]

The battle raged on for more than four hours until De Villebois was killed by a shell shrapnel. The remaining force of 54 men surrendered and from behind the hill the two women heard the joyful shouts of the British soldiers before they were allowed to continue their journey. The captured volunteers with their wounded spent the night in the Karreepan farmhouse.[xxxvii]

Patrick Campbell is amongst the British dead on 5 April 1900

34 year old Lance Sergeant Campbell was shot through the head and killed instantly during the attack, one of three Imperial Yeomanry soldiers killed, including Captain Cecil Boyle of 40th Company and Lieutenant Arthur Williams from 10th (Sherwood Rangers) Company of the 3rd Battalion. Seven British soldiers were wounded in this action.

Lord Chesham wrote to Patrick’s widow: “We attacked the enemy, Patrick Campbell was among the first (we were within fifty yards of the Boers with fixed bayonets and charging) when he fell, death being instantaneous. We, his comrades, honour him as a brave soldier…No-one was doing better in the regiment than your husband, and his loss will be much felt…we buried them by moonlight on April 6th with many a sore heart.”

The San Francisco Call reported on 8 April 1900:

SERGEANT CAMPBELL KILLED.

LONDON. April 7. 11:45 pm— The War Office has posted the list of casualties at Petersfontein, near Boshof, on April 5. Only one Is reported killed— Sergeant Patrick Campbell of the-Imperial Yeomanry, husband of the well-known actress. Nine commissioned officers and men are reported wounded.'

Sgt Davie was a member of the Diamond Fields Horse who were at the action at Boshof when Patrick Campbell was killed and recalled in his memoirs that: “…early that morning I had picked up a piece of English paper and read in it that the only private of the British Army who had the privilege of shaking hands with the Prince of Wales (afterwards Edward VII) before leaving for Africa was Private Campbell of the Yeomanry. I did not know he was with us until I heard of his death…”[xxxviii]

Doctor Osborn's account of the Boshof engagement[xxxix]

The position apportioned to our Field Hospital in the Boshof Camp was between the cemetery wall, loopholed for musketry, on the one hand, and a kopje on the other, upon which was the signalling station and an embrasure for a gun. We saw at once on getting our tents pitched that we were in a warm corner should an engagement take place, and to have blamed the Boers for firing upon the Red Cross flag would have been ridiculous, as we were placed undoubtedly in a strategical position. This proved subsequently correct, as in the plan of the night attack found in the possession of Comte de Villebois Mareuil it was at this point that the attacks was to commence, and on the very night that we took up our position.

Now began work in earnest, and the Imperial Yeomanry received their baptism of fire, and a terribly wet night it was, sufficient to damp any one’s ardour. The enemies’ forces were under the command of that very able and gallant Frenchman, Comte Villebois, who fell at the head of his gallant band of followers, who were largely composed of Frenchmen; not a Boer amongst them, for they, to the number of several hundreds, had deserted and abandoned their friends when actual fighting began. We lost two officers, Lieutenants Boyle and Williams, and Mrs Patrick Campbell’s husband, besides having several wounded. Amongst the latter was Mr A. Little, an old Eton boy, who was shot through the lungs, but who subsequently made a wonderful recovery. The wounded were brought into hospital about twelve o’clock at night, and I was oppressing their wounds until well into the morning. Amongst those brought in wounded were some nine or ten Frenchmen, Monsieur Feissal, a cousin of Comte Villebois, amongst the number. It is gratifying to know that they expressed the greatest satisfaction at the manner in which they were treated. In fact, I possess some most gratifying mementoes of their sojourn in our hospital, which they insisted upon my accepting when they bade me farewell; for, not only looking after their necessary requirements, I supplied them with tobacco and cigarettes ad lib. and wrote postcards and letters for them to their relations and friends at home.

The funeral of Comte de Villebois was one of the most impressive spectacles I have ever witnessed. It took place in the dusk of the evening, with thunder reverberating in the distance, and with an occasional flash of lightning across the sky. All the troops were drawn, up in three sides of a square, General Methuen, his staff and the French prisoners being also present. The body was carried between two lines of the soldiers, who saluted as it passed. There was no band in the camp to play the Funeral March from Saul, but what was far more impressive, all the bugles rang out in unison the call of ‘The Last Post.’ Nothing could have been more appropriate nor more in keeping with a soldier’s funeral. Lord Methuen subsequently ordered a tombstone to be erected to the memory of a true and gallant soldier, although ‘ere now an enemy.”

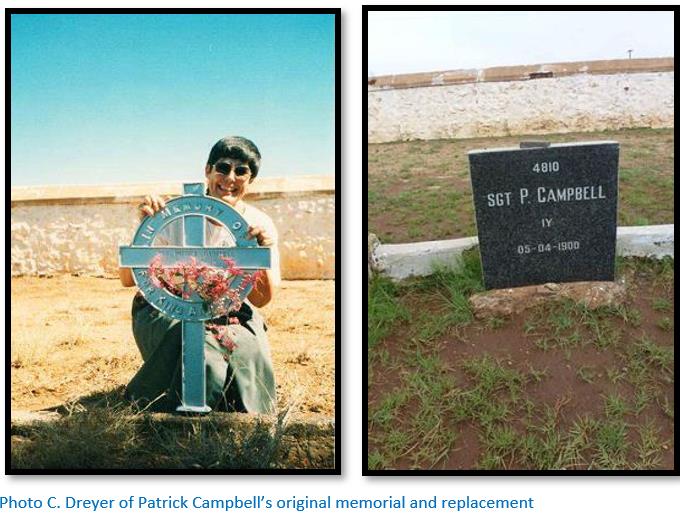

The Boshof Military Cemetery, Lejweleputswa District Municipality, Free State

At sunset on 6 April 1900, Lord Methuen, Colonel Kekewich and 1,500 British troops marched to the cemetery with its limestone walls to attend the funerals of the dead who were all given full military honours. Touched by the sombre atmosphere, Lord Methuen wrote in his journal: "I have never seen so beautiful or impressive a scene, the moon giving light to the little Dutch churchyard surrounded by cypresses." The British casualties were buried while a Dutch Reformed Church minister conducted the funerals of the Boer dead in the southern part of the cemetery.

In all there are about 120 burials in the Boshof military cemetery, a place that is rarely visited by any other than die-hard Anglo-Boer War enthusiasts. The most prominent burial is that of the Comte George De Villebois-Mareuil, who has been re-interred at Magersfontein, although his Boer comrades remain in Boshof. The Comte’s original headstone, one of two paid for by Lord Methuen during the war, however, is in its original spot, and in close proximity lie a mass grave of Boers, plus the graves of Sergeant Patrick Campbell,[xl] Captain Cecil Boyle and Lt Arthur Williams.[xli]

Lord Methuen wrote to De Villebois' only child, 16-year-old Simone including a photograph of the marble tombstone he had erected over her father's grave on which are inscribed in French the words: "In memory of the Count De Villebois-Mareuil, in life colonel of the French Foreign Legion and general of the Transvaal. Died on the battlefield near Boshof on April 5, 1900, in his 53rd year."

Dreyer writes that it was regrettable that De Villebois' remains were exhumed and reburied at the Burgher Monument at Magersfontein in 1971, as it had been his wish to be buried where he died.[xlii]

Patrick’s early life

Patrick W Campbell was born in England in 1863 and educated at Wellington College. His father had been the bank manager in Hong Kong of the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, and had settled back in England with his second wife at Sydenham Hill. Patrick had been born during his father’s first marriage, as was his brother Alan, an officer with the 72nd Seaforth Highlanders, who had distinguished himself at the battle of Tel-El-Kebir.

Patrick and Beatrice Stella Tanner first met at a card party at the house of Mrs Gifford in Dulwich in 1883 when he was twenty and she was 17 years of age, Beatrice describing Patrick in her book[xliii] as “…good looking, with unusually well-bred gentle manners, a great affection for his home and people, and a passionate love for his dead mother…He managed a boat like a magician. I remember a wonderful long day on the Thames. Pat looked only at me – the boat went without effort or sound, quick and straight.”

After four months of first meeting they eloped and were married at St Helen’s Church, Bishopsgate, in the City of London. Beatrice was already pregnant with Alan ‘Beo’ Urquhart when they eloped and Stella was born within three years.[xliv]

Most biographers of Mrs Patrick Campbell, as Patrick’s famous wife was known, state that they were separated or estranged. The reason for their separation was twofold; in that Patrick travelled extensively away from home in failed attempts to make his fortune, including travelling to Australia, Mauritius and South Africa; and that his doctor had advised him to because of his failing health, to move away from England to a healthier climate. She writes: “Pat, who had never been very strong, was ordered abroad for his health…Pat was earning less than £100 a year and his delicate health was alarming. His mother had died of consumption three years after his birth.”[xlv] “Pat’s health became worse, and at last he was ordered by the doctor to take a sea voyage. It was suggested he should go to Brisbane, where a relative of his, William Ross, was at the moment. The thought of his parting was misery to us both, but the state of his health made it imperative. It was arranged, if Pat succeeded in finding work, the children and I would join him.”

“I was sure he would soon make enough money to send for me and the children. And in those first years our dream of the joy of reunion gave our hearts courage.”

Having received Patrick’s permission to act professionally, she paid a guinea, and was signed on to Mr Baily, a theatrical agent in the Strand. Her first assignment was to play the leading lady in Bachelors, a play by Hermann Vezin for which she received £2 10s. a week and had to supply her own dresses. In My Life and Some Letters she writes: “I thought it a dazzling offer…I was out to fight for my two children and to try and make enough money to bring Pat home to us more quickly.”[xlvi]

She writes: “Pat’s letters came seldom. Sometimes he was out of a job, or down with malaria, sometimes succeeding for a few months and then a cheque would come. Sometimes he was cut off from all communications with the outer world by the flooded rivers. Then I used to think he had died of fever, or that he had been mauled by a lion.”[xlvii]

Mrs Pat Campbell’s acting career takes off

Mrs Patrick Campbell (1865-1940) was the most successful British stage actress of her generation. She was born Beatrice Stella Tanner in London, of English and Italian parents. She made her stage debut in 1888, four years after her marriage to Patrick Campbell.

Her first great success was as Paula in ‘The Second Mrs. Tanqueray’ by Sir Arthur Pinero in 1893. Beatrice writes: “I was engaged at a salary of £15 a week, at a fortnight’s notice and to rehearse on approval. So I can scarcely flatter myself that either Mr Pinero or Mr George Alexander thought anything of me beyond my looks. The salary seemed very generous to me after my £8 a week at the Adelphi. Both author and manager were worried and anxious at rehearsals. I heard afterwards that more than one management had refused The Second Mrs Tanqueray, considering the play too risqué.”[xlviii]

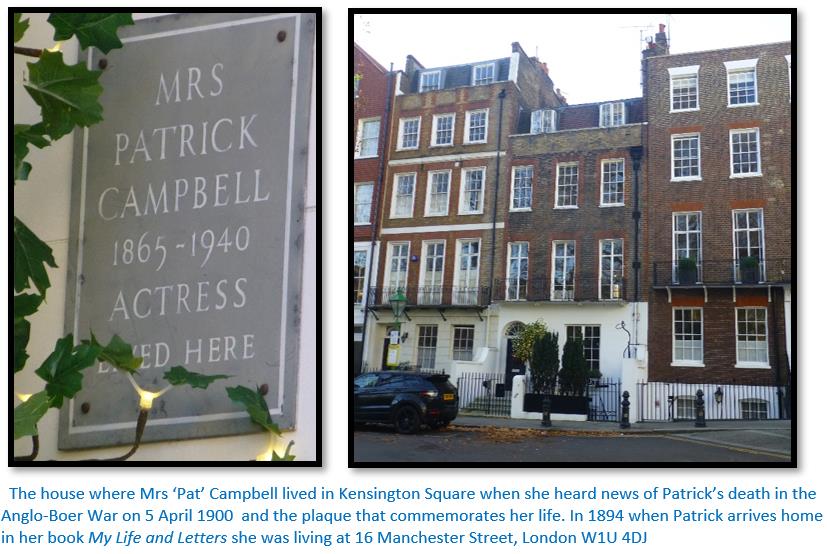

News of Patrick’s death on 5 April 1900

Beatrice was now managing the Royalty Theatre with some success from both the critics and the public. But then the Boer War broke out in October 1899 followed by Queen Victoria’s death on 22 January 1901 which emptied the theatres for many weeks. Patrick had decided to join the 10th Imperial Yeomanry and wrote:

White Hart Hotel, Buckingham. Dearest Stella, I am hard at work down here and everything looks bright for me. I messed with Lord Chesham and all his officers last night; they were all very nice to me and I think I shall be of great service to him. I easily passed my riding and shooting test and see the doctor tomorrow. I understand I shall have no difficulty in passing my medical. Chesham has asked me to stay down tomorrow and help inspect some recruits and horses. They have a splendid lot of men here and he hopes to get us off by the 20th at the latest…”

She says: “At home we were all anxious. Pat had decided to join Lord Chesham’s Yeomanry and he left for Africa towards the middle of March 1900. On April 5 poor Pat was killed. I remember how I heard the news. My uncle met me at the theatre. It was Saturday, there had been two performances. He said – ‘Let us drive to the War Office and see if there is any news.’ He told me to wait in the hansom. He returned in a few minutes saying: ‘there was no news.’ For the rest of the drive he was silent.

When we arrived at my house in Kensington Square we went in and sat in the dining room. I noticed how white and drawn his face was and how questioningly he looked at me. I spoke of my plans at the theatre. Suddenly there was a knock at the front door. I opened it. Mr Shackle – Pat’s friend and my acting manager – stood there. He said: ‘it’s true.’ I said: ‘what’s true?’ ‘Pat is killed.’ I realised that uncle had known all the time.[xlix]

The telegram from Lord Chesham read: “Patrick Campbell was killed instantaneously in final attack and was buried with military honours in Boshof cemetery. I have written you full details. Camp Moliens Farm, Orange Free State, 10th Imperial Yeomanry.”

Chesham’s letter: “…We attacked the enemy. Patrick Campbell was among the first (we were within 50 yards of the Boers with fixed bayonets and charging) when he fell, death being instantaneous. We, his comrades, honour him as a brave soldier and the ten prisoners (chiefly Frenchmen) also said to me how gallantly our men had fought. No one was doing better in the regiment than your husband and his loss will be much felt. We lost two officers besides and our three brave comrades now lie in the cemetery at Boshof, with the French general (who was killed in the action) De Villebois-Mareuil, near to their graves.

We buried them by moonlight on April 6th, with many a sore heart as the bugle sounded ‘The Last Post’ over the graves of three as brave Englishmen as had fallen in the war.”

Her career after Patrick’s death

Not all her theatrical productions were a success – a provincial tour ended with a loss of £6,000, but a tour of 22 weeks in the United States saved the situation and she was rescued from bankruptcy. Among her famous Shakespearian roles were Juliet, Lady Macbeth and Ophelia. She also starred as Mélisande in Maeterlinck's ‘Pélleas and Mélisande’ and in the title roles in Ibsen's ‘dedda Gabler’ Hofmannsthal's ‘Elektra’ and Yeat's ‘Deirdre.’ In 1914 she created the role of Eliza Doolittle in Shaw's ‘Pygmalion’ though much too old for the part, she was the obvious choice, being by far the biggest name on the London stage.

After World War I, she played few new roles, mainly recreating her former starring parts on tour in the United States and England. During the 1930's she also played minor roles in several American films.

Beatrice continued her life as an actress and was involved in a long-time affair with George Bernard Shaw. Fourteen years after Patrick’s death she became the second wife of George Cornwallis-West, a writer and soldier previously married to Jennie Jerome, the mother of Sir Winston Chuchill. She writes: “Then in the unexpected way things sometimes happen in this world, George Cornwallis West was seriously attracted by me. I believed his life was unhappy and warmly gave him my friendship and affection. This caused gossip, misjudgement and pain that cannot be gone into here.”

Despite her second marriage she continued to use the stage name "Mrs Patrick Campbell."

In 1909 her son Beo married an American girl and said they would soon be returning. “Stella and I set to and we worked hard. Everything that could be spared from our little house we carried into the small flat we had found for them on the other side of Kensington Square. And they came – he full of pride, she all loveliness and charm. Her delightful manners and witty way of expressing herself won the heart instantly; and then there were her pretty clothes, her freshness and gaiety, making Kensington Square a garden of flowers.”[l]

Her letters after 1927,[li] clearly reveal the decline in her fortunes, her inability to find work, and her constant money difficulties.

Patrick and Beatrice’s son, Beo, was killed in action in the Great War on 30 December 1917 as acting Lt-Commander in the Royal Navy but gazetted as a Captain in the Highland Light Infantry with whom he was serving at the time. During the war he had fought at Gallipoli, at Passchendaele, and Cambria, being killed on the Welsh ridge. He had been awarded a Military Cross on 1 January 1917 and the bar to the MC on 17 January 1917.

Beatrice was playing in The Thirteenth Chair at The Duke of York’s when she received the telegram: “Admiralty. Deeply regret Acting Lieutenant-Commander Alan U. Campbell killed in action, 30th December. Letter follows.”

Beo and his commander were killed instantaneously by a shell near La Vacquerie, at about half past seven in the morning of December 30th and were buried on January 1st at Metz-en-Couture.[lii]

She died at Pau, France of pneumonia on 9 April 1940, aged 75 years old.

References

Mrs P. Campbell. (Beatrice Stella Cornwallis-West) My Life and some letters. The Ryerson Press. Toronto.

Also online at https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/20889975/open-209-mb

R. Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, 1976

A. Darter. Pioneers of Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series, Bulawayo, 1977

C. Dreyer. 15 Oct 2015. First phase archaeological and heritage assessment of the proposed Riverton – Boshof – Dealesville water pipe line, Free State. Anglo-Boer War History, Archaeological and Historical background

A.S. Hickman. Men Who Made Rhodesia. The British South Africa Company, Salisbury, 1960

H.F. ‘Skipper’ Hoste. Rhodesia in 1890. Rhodesiana Publication No 12, September 1965. P1 – 26

A.G. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia Vol 32, Bulawayo, 1973

S. Lunderstedt. https://africaunauthorised.com/sos-steve-on-sunday-31/01/2021

J. Shigley. 29 May 2017. The Diamond Fields of South Africa: Part 1 (1868-1893) https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/historical-reading-diamond-fields-...

Dr Osborn’s account from https://www.angloboerwar.com/forum/6-places/28958-boshof

N. von der Hyde. Field Guide to the Battlefields of South Africa. Struik Travel & Heritage, Cape Town, 2013

Notes

[i] africaunauthorised.com/sos-steve-on-sunday-31/01/2021

[ii] My Life and some letters, P30

[iii] Named the Eureka, discovered in 1867 weighing 21.25 carats, it was later cut to a 10.73 carat cushion-shaped brilliant

[iv] The Diamond Fields of South Africa: Part 1 (1868-1893)

[v] The Star of South Africa is a pear-shaped diamond weighing 47.69 carats. It was cut from the rough stone weighing 83.5 carats when discovered in 1869 by a Griqua shepherd on the banks of the River Orange in the same area that the Eureka diamond was found.

Schalk van Niekerk, who had been given the very first discovered diamond by the wife of Daniel Jacobs, recognised the stone as a diamond and bought the diamond, it is said, for 500 sheep, 10 oxen and a horse.

He then sold it to the Lilienfield Brothers of Hopetown for £11,200. This sale had a huge impact on the region as it marked the start of the rush of many operators to South Africa.

It changed hands twice before being sold to the Earl of Dudley for £25,000.

A replica of The Star of Africa can be viewed today at the Natural History Museum in London.

[vi] The Diamond Fields of South Africa: Part 2 (1893-2014)

[vii] Wikipedia: Big Hole

[viii] My Life and some letters, P30

[ix] africaunauthorised.com/sos-steve-on-sunday-31/01/2021

[x] The Pioneer Corps, p123

[xi] Ibid, P124-5

[xii] Men Who Made Rhodesia, P347

[xiii] Major-General Methuen was Adjutant-General of British Forces in South Africa and had been instructed by High Commissioner Loch to ensure the Pioneer Corps were sufficiently trained to undertake the march to Mashonaland

[xiv] Rhodesia in 1890, P

[xv] Men who Made Rhodesia, P347

[xvi] Pioneers of Mashonaland

[xvii] My Life and some letters, P52

[xviii] This could be William Filmer Usher (1851 – 1916) who came to Bulawayo from Bathurst in the Eastern Cape with his brother and lived as a farmer and trader until his death in 1916 at Sauerdale, Bulawayo. His brother Reuben (1853 - ?) died of malaria leaving no descendants and was buried at Gwanda.

[xix] The Inxwala, or festival of the first fruits, to thank the ancestors and God for a bountiful harvest and loyalty to the King was shown at the ceremony

[xx] John Smith Moffat, (1835 – 1918) was the son of Robert and Mary Moffat and was Assistant Commissioner in Bechuanaland to Sir Sydney Shippard, the Resident Commissioner

[xxi] I can find no reference to Arndt amongst the Pioneer Corp and prospectors who accompanied it in Robert Cary’s book or in A.S. Hickman’s BSA Company Police. There is a James Carlisle Arnold (Trooper No 564) listed in the BSA Company Police who went prospecting after discharge and died of jaundice in Gwelo hospital on 1 August 1896

[xxii] The ‘Kaiser Wilhelm’ goldfields are at Makaha on the Ruenya river. Approximately 50 km north east of Mutoko

[xxiii] Karl Mauch (1837 – 1875) see the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xxiv] Alexander Tulloch (1859 – 1940) Pioneer Corps No 145 where he served on the Gardner gun in Troop C. Prospector, mining, auctioneer and farmer well-known in Manicaland

[xxv] Victor A.L. Morier, BSA Company Trooper No 540, later Sub-Lieutenant. Originally in E Troop, I January 1891 he was promoted into A Troop. Accompanied Capt Heyman in the negotiations as he spoke Portuguese. They proved fruitless and the Portuguese attacked Chua hill on 11 May 1891. (See the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) Died at sea returning to Cape Town after leave in England.

[xxvi] The Pioneer Corps, P68

[xxvii] My Life and some letters, P31

[xxviii] Ibid, P92

[xxix] Riverton – Boshof – Dealesville water pipe line

[xxx] Field Guide to the Battlefields of South Africa, P258

[xxxi] Ibid, P258

[xxxii] Miss Lenie Enslin would marry Chris van Niekerk, President of the Senate in the pre-democratic South African Government) (Hopkins 1963)

[xxxiii] https://bmmt.co.uk/test/Bucks Yeoman in action at Boshof, South Africa

[xxxiv] https://bmmt.co.uk/test/ from the Buckingham Express 5 May 1900

[xxxv] https://bmmt.co.uk/test/ A memorial stone on the kopje held by the volunteers was unveiled in 1987

[xxxvi] Field Guide to the Battlefields of South Africa, P259

[xxxvii] This information from the article Riverton – Boshof – Dealesville water pipe line

[xl] He is also commemorated on the Buckinghamshire Boer War memorial at Coombe Hill, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire (see: https://www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk/memorial/115006).

[xlii] Riverton – Boshof – Dealesville water pipe line

[xliii] My Life and some letters, P24

[xliv] In her book she writes her parents John Tanner (1829–1895) and Maria Luigia Giovanna ("Louisa Joanna") née Romanini (1836–1908), daughter of Count Angelo Romanini, fell hopelessly in love at their first meeting – my mother could not speak a word of English and my father not a word of Italian. He was twenty-one, she was seventeen.

[xlv] My Life and some letters, P26

[xlvi] Ibid, P38

[xlvii] Ibid, P46

[xlviii] Ibid, P66

[xlix] Ibid, P148

[l] Ibid, P236

[li] University of Chicago Library

[lii] My Life and some letters, P328