Kenneth Kaunda who died on 17 June 2021 aged 97; the last of Africa’s true Independence leaders and one of the few that stepped down

Kenneth Kaunda, first president of Zambia following Zambia’s independence in 1964 and the last of his generation who fought colonialism, was admitted to a military hospital in the capital, Lusaka, where he passed away. Current president Edgar Lungu said the country was in mourning and wrote: "I learnt of your passing this afternoon with great sadness. On behalf of the entire nation and on my own behalf I pray that the entire Kaunda family is comforted as we mourn our first president and true African icon."[i]

Why “KK” was so different from the current generation of African leaders

Deeply religious, he led a mostly peaceful struggle that was influenced by Gandhi’s ideals of non-violent resistance. In speeches and interviews before independence he urged reconciliation with Britain, which had jailed him twice.[ii]

Africa today is a lesson in the futility of democracy; the continent is overrun with dictators who stay in office for decades and one-party states that cling to power. True democracies are the rare exception, not the rule. Some of these dictatorships have ended in assassination or military coups, almost all have forgotten the original dreams of their citizens and the promises that were made to them.

KK was the last of those pioneer leaders who threw off colonialism in favour of independent statehood. He was a living reminder of a committed pan-Africanist who wanted to build a new Zambia that was free to determine its own way in international affairs.[iii] These laudable aims have now sadly become lost by the current generation of political leaders in their corrupt scramble for personal wealth at the expense of their citizens – in so doing they mortgaged their country’s futures to authoritarian states like China.

The Wind of Change

On 3 February 1960 in Cape Town’s all-white Parliament the UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, fresh from visiting several British African colonies, delivered his now-famous "Wind of Change" speech in which he announced that Britain would grant independence to its colonies.[iv]

By 1961, 17 African countries had gained independence and Ade Daramy and his school classmates could proudly reel off the names of the leader of every independent African nation, including Milton Margai of Sierra Leone, Dawda Jawara of The Gambia, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Ahmed Sekou Touré of Guinea, Modibo Keïta of Mali, Léopold Senghor of Senegal and Kenneth Kaunda.

Born in Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia

Kenneth David Buchizya Kaunda was born on 28 April 1924 at Lubwa, near the border of what was then the Congo in the British colony of Northern Rhodesia, the youngest of eight children. His father, Reverend David Kaunda, was the first African Church of Scotland missionary to be sent to Lubwa and his wife, one of Africa’s pioneering teachers, baptised him Buchizya, which meant “the Unexpected One” as he was born in the 20th year of their marriage.

Childhood

His father died when Kenneth was only eight years old, so that after school he had to help with the family chores. “I was made to do every type of work around the house and in the garden,” he recalled. “I carried water from the well two miles away. I learned to kneel by the grinding stone and grind the millet for the evening meal. I swept and cleaned the cooking pots and ironed my clothes.”

He paid endless tributes to his mother, who brought him up, and he said he owed everything to her; in early life deciding to be a minister and teacher like his father. Away from his studies he earned money for family expenses by digging irrigation ditches and tending the garden at the church mission.[v]

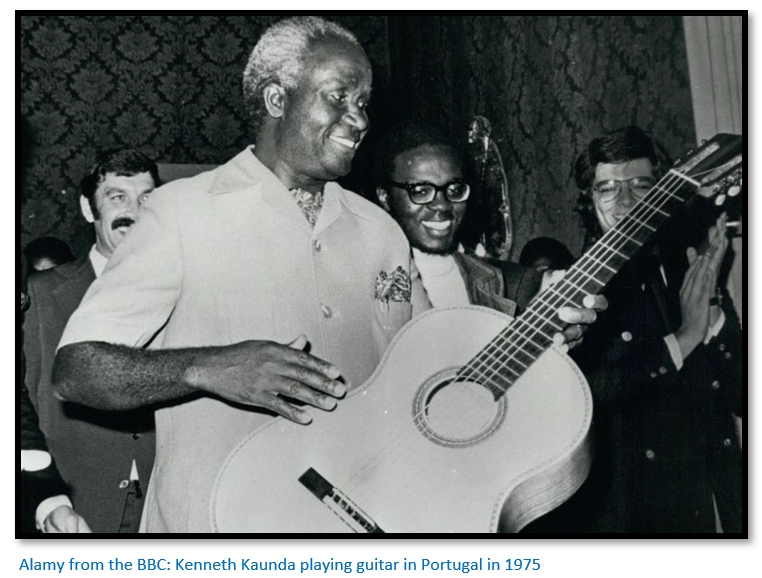

At school, he did well in the classroom and at sports and found time to learn to play the guitar. During school holidays he toured the Copperbelt region as a musician and singer.

His early life was as a teacher

He started his career teaching at a mission school near Salisbury, capital of Southern Rhodesia, and then at a secondary school in Mufulira in the Copperbelt of Northern Rhodesia. However Kaunda was saddened rather than angered by the way the whites treated the blacks in the country and decided to leave teaching and enter politics to end racial discrimination and segregation.

One of his first political acts was when he saw a group of African women protesting at the high price of meat in a white butcher’s shop and then being hustled outside for their nerve, was to become a vegetarian in protest at what his people could not afford.[vi] In his nineties, he put his long life down to his diet, saying: “I eat only vegetables, like an elephant.”[vii]

Early life in politics

He helped to found the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress and became district secretary of a local branch in Chinsali District. After three years in 1953 he rose to the office of the party’s secretary-general, which automatically made him the chief lieutenant of Harry Nkumbula, president of the newly renamed (Zambian) African National Congress. The party however failed to mobilise black Africans against the white-ruled Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

As editor of its news sheet, Kaunda attacked the policies of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland formed in 1953. He condemned the colour bar and was arrested and sentenced to two months in jail for possessing banned literature. In prison, he decided to give up smoking and drinking for the remainder of his life.

Formation of a new political party, the Zambian African National Congress

In 1957 Kaunda toured Britain and India and fell under the influence of Mahatma Gandhi who followed the religious principle of ahimsa (doing no harm) common to Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism and turned it into a non-violent tool for mass action.

This formed the basic principle of a new political organisation he founded on his return to Northern Rhodesia when in October 1958, Kaunda broke away from Nkumbula, who had refused to oppose a new British constitution, which ignored many demands made by the Congress party. By now he was disillusioned with what he saw as the failure of his party to take a stronger line on the rights of indigenous Africans.[viii]

Kaunda became president of a new party, the Zambian African National Congress, that took a stronger, if non-violent, line with the colonial authorities. He called on his 75,000-strong membership to boycott elections in 1959 because they believed the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland had been created by white settlers to exploit the Africans.

He travelled the country and became known for his guitar playing, composed liberation songs and began campaigning against colonial rule.[ix]

Sentenced to prison

Kaunda was arrested for organising “an unlawful assembly” and distributing leaflets that the authorities deemed subversive, the party was banned, he was sent to a remote part of Northern Rhodesia, before being imprisoned in Salisbury.

He described his nine months in prison as: “the most terrible months of my life” suffering from malaria, dysentery and other illnesses. He became more convinced that his people could find freedom only through a policy of non-violence, arguing: “It is no good trying to lead my people to the land of their dreams if I get them killed on the way.”

His imprisonment however had turned him into a radical.

KK forms a new political party, United National Independence Party (UNIP)

In January 1960 he was released from prison and became head of the newly formed United National Independence Party (UNIP) and resumed his campaign against the Federal government of Sir Roy Welensky. He dismissed a proposed constitution offering 22 legislative seats to 70,000 whites and 8 seats to 3,000,000 blacks as “unchristian, unethical, impolite and unworkable.”

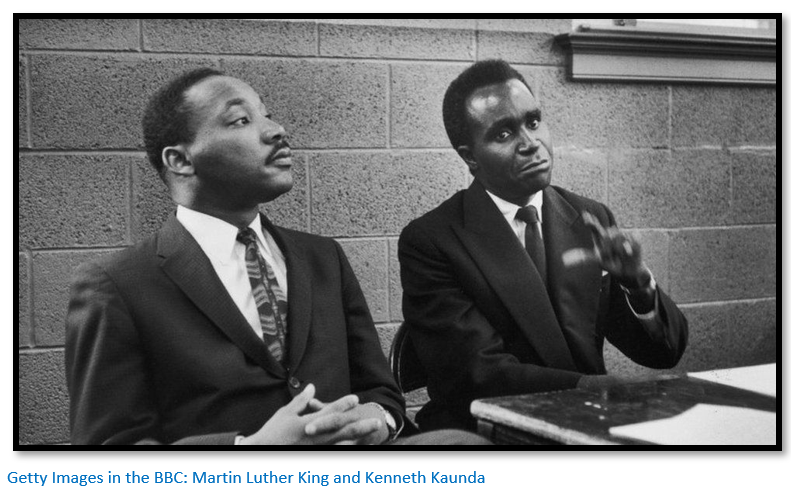

Fired with enthusiasm following a visit to Martin Luther King in the US, he began a campaign of civil disobedience in Northern Rhodesia which involved blocking roads and burning buildings.[x]

1962 Elections

Elections were held in October 1962, but UNIP failed to win a majority vote, so Kaunda linked up with Nkumbula’s ANC to form an uneasy and fragile coalition, and the first African government of Northern Rhodesia. Kaunda was appointed minister of local government and social welfare and almost immediately announced that he would seek a new constitution enabling Northern Rhodesia to break away from the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Dissolution of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1963

On 31 December 1963 the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was dissolved and in the following month after elections UNIP won a landslide victory winning 51 of the 75 seats in the first “one man-one vote” election in Northern Rhodesia.

First Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia

At 39 year old, Kaunda was elected the youngest prime minister in the Commonwealth and was soon on his way to London to secure a promise of independence before the end of the year. Returning home, he faced a full-scale uprising by the Lumpa religious sect led by the prophetess, Alice Lenshina.[xi] During a three-week reign of terror, 700 men, women and children were killed before the government quelled the rebellion.

His wish, he said, was for Zambians to have an egg on their table for breakfast every morning, a pint of milk and for every Zambian to have a pair of shoes on their feet.[xii]

Northern Rhodesia gains independence and becomes Zambia

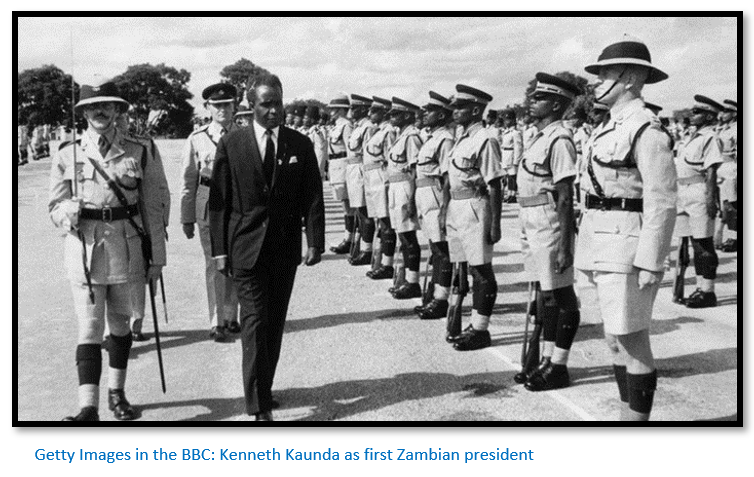

On 25 August 1964 Kaunda was elected president-designate and two months later on 24 October Northern Rhodesia became the Republic of Zambia, the ninth British colony on the continent to win independence and Africa’s 36th to achieve that status. Kenneth Kaunda became the first President.

Zambia remained within the Commonwealth; Kaunda launched reforms in agriculture and education and assured white civil servants and technicians that they had a future in Zambia. The country entered independence with the great advantage of having a stronger economic base than any of its neighbours through its copper resources, but there was a great shortage of native Zambians who had the skills and training to run the country.

Southern Rhodesia declares unilateral declaration of independence on 11 November 1965

Zambia’s position was also gravely imperilled by Ian Smith's unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) in Southern Rhodesia. Sanctions imposed by the British government on Rhodesia proved at least as damaging to the Zambian economy.

However KK considered the economic sanctions and oil embargoes imposed on Rhodesia to be inadequate and said that if Britain failed to take stronger measures, he would propose that she should be expelled from the Commonwealth.

In 1969 Kaunda nationalises Zambia’s copper mines

The output of the Copperbelt accounted for 90% of Zambia’s foreign exchange earnings. But soon after nationalisation the price of copper collapsed, imported oil prices soared, and the economy, already weakened, was soon suffering serious economic distress.

As Chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) KK travelled abroad so often that both Western nations and his own citizens became completely disillusioned with him as the entire Zambian government machinery came to a halt with nobody prepared to take decisions.

At independence Zambia was one of the richest countries in sub-Saharan Africa, but by 1991 it had debts of $8bn.[xiii] Poor economic management caused his popularity to nose-dive, and Zambians voted KK out of office when free elections were held in 1991.

Corruption and poor economic policy drove the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to demand severe austerity measures, but in 1987 the IMF was told their remedies were too harsh and were ordered out the country. Inflation rose and ordinary Zambians living standards fell until KK agreed to a new IMF programme in return for international loans.[xiv]

On the frontline with Rhodesia

Kaunda was chairman of the frontline states (Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe) in the campaign against apartheid, leading opposition first to Ian Smith in Rhodesia and then the regime in South Africa. In pursuit of a solution in Rhodesia, he had meetings with South African leaders John Vorster, PW Botha and FW de Klerk. In August 1975 KK met the South African prime minister John Vorster in a railway carriage on a bridge spanning the Victoria Falls to act as “honest broker” in failed talks between Smith’s government and the Rhodesian African National Council (ANC)

Historically, Zambian copper exports had been sent by train and road across Rhodesia to South African ports, but as a leader of the frontline states he closed his border and instead used the poorly constructed Tanzam Railway that the governments of Tanzania, Zambia and China built to eliminate landlocked Zambia's economic dependence on Rhodesia and South Africa.

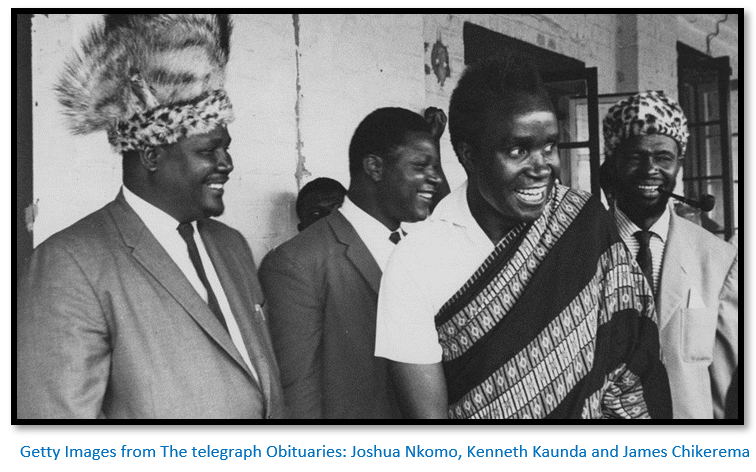

He gave sanctuary to freedom fighters from Joshua Nkomo’s ZAPU movement that was resented by Mugabe’s ZANU-PF and harboured political exiles from South Africa’s ANC in Zambia; both countries carried out military and economic sabotage against Zambia and KK clashed with Margaret Thatcher over her opposition to sanctions against the apartheid regime. During the Rhodesian UDI crisis KK threatened to expel Britain from the Commonwealth organisation for failing to send troops to end the rebellion.

Increasing domestic political opposition

At the beginning of his Presidency KK made great strides to improve the living standards of Zambians and succeeded in uniting the country under his slogan ‘One Zambia, One Nation.’

But his economic policies turned Zambia with its rich copper resources into a state in which poverty remained widespread and life expectancy was among the lowest in the world, much as Robert Mugabe did in Zimbabwe. Like Mugabe he became intolerant of criticism and in the face of increased political opposition in 1972 he declared Zambia a one-party state. KK was the only candidate in elections in 1978, 1983 and 1987 – changing the rules of his own party to keep getting selected as the only candidate and allegedly gaining more than 80% of the vote each time.

The situation was not relaxed until 1991, when free elections were held. He said: "It would have been disastrous for Zambia if we had gone multiparty, because these parties would have been used by those opposed to Zambia's participation in the freedom struggle."[xv]

In late 1980 there was reports of an attempt to overthrow his government, and a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed over much of the country. In the next 10 years, there were reports of two further attempts to topple his government. The last of which, in the summer of 1990, followed food riots in Lusaka, the capital, and the Copperbelt region, over the government's crash austerity programme. More than 20 people died in three days of rioting, and the security forces stormed the campus of Zambia University and closed it to shut down unrest.[xvi]

Increased domestic / international calls for democracy and a rejection of a one-party state

KK eventually gave way after nearly two decades of one-party rule and agreed to elections on 31 October 1991. There was little surprise in Zambia that the public felt he had overstayed his time in office and KK’s party was rejected in favour of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy led by Frederick Chiluba. UNIP took only 24% of the vote and he stepped down from power.

Kaunda now seen as a threat to Zambia’s security

Although no longer in power Kaunda still had great influence in Zambia and the new government saw him as a threat. He was arrested on charges of treason in 1997, although charges were dropped after international pressure and a later attempt to have him declared stateless was eventually thrown out by the country’s courts in 2000.

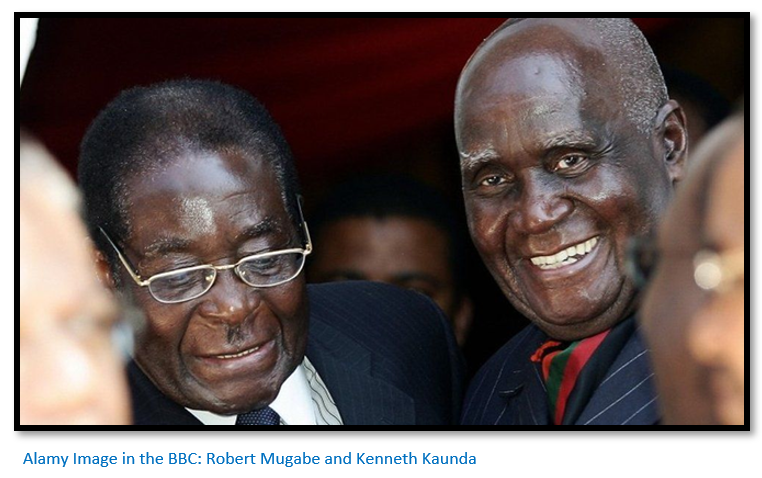

KK and Robert Mugabe

Unlike the long-time president of Zimbabwe, KK was always a moderate, dedicated to multiracialism, and always hoped for a peaceful evolution that would accommodate white Africans as well as black.[xvii] Despite misgivings, he remained a staunch defender of Mugabe's policy of land reform, under which white farmers were driven from the country, resulting in economic meltdown. "I've been saying it all along, please do not demonise Robert Mugabe. I'm not saying the methods he's using are correct, but he was put under great pressure." Of course, Robert Mugabe and ZANU-PF were under great pressure; they were about to lose the 2000 constitutional referendum election to the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC)

Fighting the Southern Africa HIV epidemic

When his son Masuzyo died of an Aids-related disease, KK was one of the first prominent Africans to acknowledge the terrible toll of the epidemic on all sections of African society including children, young people, adults, women and men. Until then the subject had been taboo, KK’s acknowledgement of HIV and his own personal tragedy has led to much greater awareness in methods to avoid the transmission of the disease which has created so many orphans on the African continent.

He told Reuters in 2002: "We fought colonialism. We must now use the same zeal to fight Aids, which threatens to wipe out Africa."[xviii]

The multi-talented Kenneth Kaunda

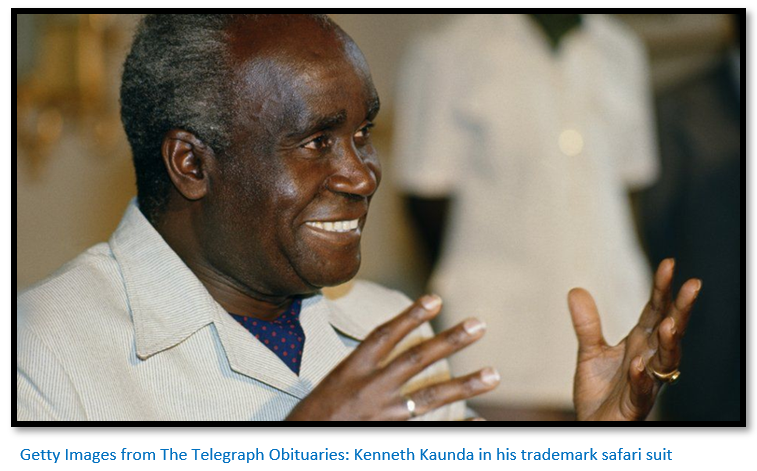

KK wrote a number of books putting forward his ideas on African Socialism which were absorbed by other African leaders, including Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania. Apart from being an accomplished guitar player he was a keen ballroom dancer with his wife. KK was known for wearing safari suits (safari jacket paired with trousers) still commonly referred to as a "Kaunda suit" throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

KK had great personal charm and was respected and on friendly terms with many of the world’s leaders. His speeches were infused with his Christian faith, a choking voice and tears wiped away with a white handkerchief-waving before he became Africa’s elder statesman. An open admirer of the Queen and a relentless critic of Margaret Thatcher, KK ruled Zambia for 27 years with a paternalism that blended humility, compassion and sobriety and initially with a ruthless intolerance for any opposition.

His wife, Betty Kaunda died on 19 September 2012 aged 84 years. They had eight children and adopted an orphan; and left thirty grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren.[xix] The family often accompanied KK and Betty in hymn-singing around the piano and Bible readings. KK was always an early-riser, prayed frequently, followed an abstemious regime that excluded smoking, drinking and meat and worked a 16-18 hour day.[xx]

The Economist said of KK in their tribute to him: “Kenneth Kaunda was a bad Zambian leader but a great ex-president.”

Kenneth Kaunda, born 28 April 1924: died 17 June 2021

References

Ade Daramy. Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history. The BBC, 9 May 2021

Telegraph Obituaries. Kenneth Kaunda, Zambian president and elder statesman of Africa – obituary. 17 June 2021

BBC. Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's independence hero: www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-160394 18 June 2021

BBC. Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's first president dies aged 97. 17 June 2021

The Economist. Middle East & Africa Desk. Kenneth Kaunda was a bad Zambian leader but a great ex-president. 18 June 2021

Notes

[i] Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's first president dies aged 97

[ii] Kenneth Kaunda was a bad Zambian leader but a great ex-president

[iii] Zambia's independence hero

[iv] Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history

[v] Kenneth Kaunda, Zambian president and elder statesman of Africa

[vi] Zambia's independence hero

[vii] Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history

[viii] Zambia's independence hero

[ix] Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history

[x] Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's independence hero

[xi] Wikipedia: Alice Lenshina founded and led the Lumpa Church, a religious sect that embraced a mixture of Christian and animist beliefs and rituals. The Lumpa Church rejected the authority of any "earthly government", it refused to pay taxes and it established its own tribunals.

[xii] Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history

[xiii] Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's independence hero

[xiv] Kenneth Kaunda, Zambian president and elder statesman of Africa

[xv] Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's independence hero

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Kenneth Kaunda: Zambia's independence hero

[xviii] Zambia's first president dies aged 97.

[xix] Wikipedia: Kenneth Kaunda

[xx] Kenneth Kaunda, Zambian president and elder statesman of Africa