Edward Carey Tyndale-Biscoe who raised the flag at Salisbury, now Harare on 13 September 1890

A summary of his remarkable career

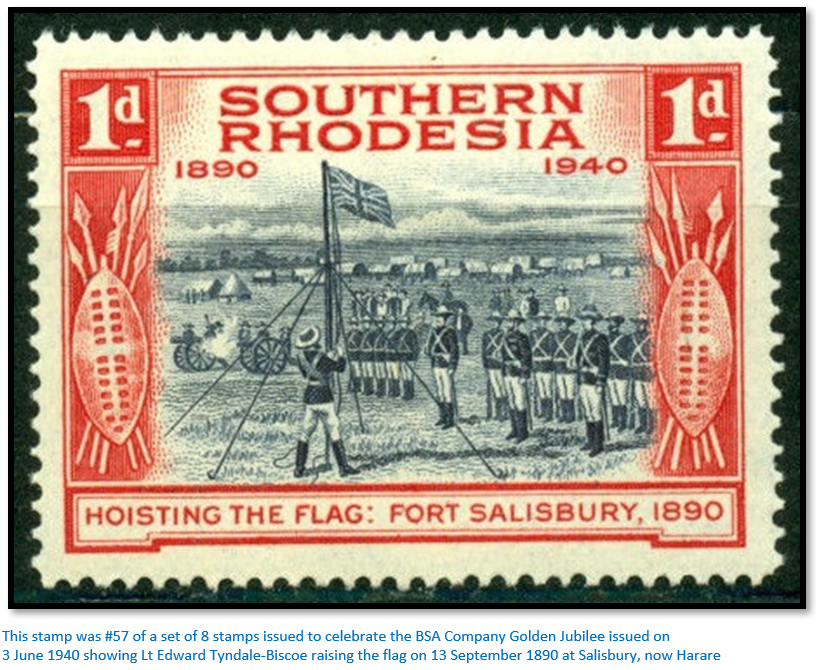

On 10 December 2014 an important set of medals awarded to Commander Edward Carey Tyndale-Biscoe, was auctioned at Dix Noonan Webb. Tyndale-Biscoe is known to many Zimbabwean historians for hoisting the Union Jack at Fort Salisbury on 13 September 1890 at the end of the Pioneer Column’s occupation of Mashonaland.

What is not so well-known is that he served in the Royal Navy and fought with gallant distinction in Egypt and the Sudan at the Battles of El Teb and Tamai. Invalided from the Navy with a stammer he was appointed in 1890 as lieutenant in C Troop of the Pioneer Column because of his experience with machine guns.

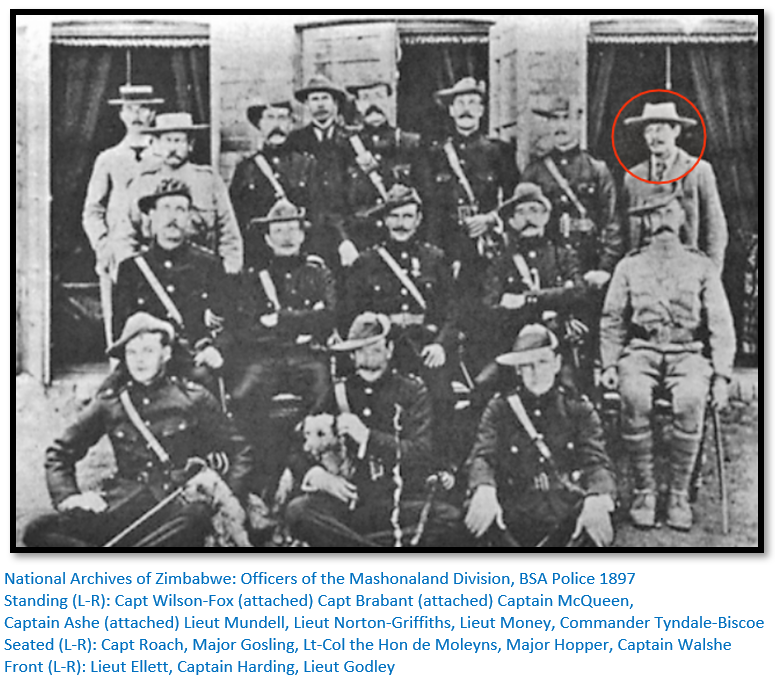

In 1893 he served in the Salisbury Horse and commanded the ‘galloping Maxim’ and fought at both the battles of Shangani and Bembesi before playing his part in the 1896 Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona (First Chimurenga) Rebellions. In 1897 he served with the British South Africa Company’s (BSACo) Police in Mashonaland before returning to civilian life.

In 1899 he volunteered once again and gained a “mention in despatches” and special promotion for his part in the defence of Ladysmith during the 1899-1902 Anglo-Boer War. A separate article on this website Letters from the Siege of ladysmith by Edward Carey Tyndale-Biscoe covers this exciting period of his career and is included under Harare province.

Most of the information for this article is from the book ‘Sailor Soldier’ written by his grandson David Tyndale Biscoe. Edward kept up a great correspondence with his next elder brother Cecil who joined the Church Missionary Society, but was not that concerned with converting Kashmiri’s to Christianity and more with teaching their children to live an active Christian life and support the weak and fight corruption wherever it occurred in the six boys’ and one girls’ school he founded. The Missionary and the Maharajas; Cecil Tyndale-Biscoe and the Making of Modern Kashmir written by another grandson, Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe and published by Bloomsbury, makes a fascinating read.

Schooling and training in the Royal Navy

Edward Carey Tyndale-Biscoe was born in Holton, Oxfordshire on 29 August 1864, the fifth of eight children (fourth son) of William Earle Tyndale (later Tyndale-Biscoe) and Eliza Carey (née Sanderman) His father had inherited Holton Park from his uncle, Elisha Biscoe and the family name was changed by deed poll to Tyndale-Biscoe in 1883.

He was educated at Foster’s School, Stubbington in Hampshire, prior to joining the training ship HMS Britannia as a cadet aged 14 years old in January 1878. Among his fellow classmates were the Prince Albert and Prince George, otherwise known as “Sardine” and “Sprat” before passing out of training in December 1879 and moving on as a cadet to HMS Minotaur (1863) His training had emphasised physical fitness and initiative which attributes served him throughout his life.

‘Great coolness and gallantry’ with the bluejackets in Egypt & the Sudan

In 1881 at 17 years old he was promoted to midshipman sailing in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic before the crew were paid off and Tyndale-Biscoe joined HMS Euryalus in Malta which was a three masted sail cruiser with her steam engine being used when they were short of wind or in a hurry. Initially they steamed through the Suez Canal and sailed via Aden for Sri Lanka.

Whilst there the ship received orders to sail for Egypt to support the Mediterranean fleet in the bombardment of Alexandria. On 28 July 1882 the ship’s naval brigade landed to the south of Suez town whilst General Tanner and the marines came from the north in a pincer movement and as the Egyptian garrison had already left, they occupied the town, Tyndale-Biscoe being on duty running the Admiral’s barge ferrying troops and materials between the Euryalus and shore.

Further skirmishes followed close to the canal with the Egyptians being driven from their positions. HMS Euryalus left the conflict area on 12 October for Jeddah and Aden and crossed the Indian Ocean to Bombay, now Mumbai where the crew were treated to a hero’s dinner. Ceylon which he calls “The Sober Island” had a navy training school which he remembered for sport and rowing regattas before they left in February 1883 for Rangoon, now Yangon in Myanmar. This voyage continued around the Indian Ocean to Mauritius in May and to Zanzibar by September before returning to Mumbai.

Euryalus left Mumbai on 4 December 1883 going west to Aden and then to Suakin on the Red Sea. The Egyptians had been defeated on 13 September 1882 at Tel-el-Kebir near Cairo by General Sir Garnet Wolseley, but a new threat had emerged from the desert in the form of the Mahdi and his followers. The Dervishes had severely defeated several Egyptian forces and now threatened General Gordon in Khartoum and the Red Sea route to India.

Euryalus’ task was to undertake another amphibian landing at Suakin from which led the shortest route to Khartoum. When they arrived off Suakin on 17 December 1883 the town was defended by two thousand Egyptian soldiers and besieged by twenty thousand Dervishes in the nearby hills. Shortly before on 9 December seven hundred Egyptians had gone out on a sortie and were so badly defeated that only nine wounded survivors made it back to the town.

On 27 January 1884 both infantry and cavalry forces moved to Trinkitat in three steamers with the task of relieving the inland town of Tokar from the Dervishes. General Baker’s force of four thousand men advanced in a square and when the Dervishes attacked in thousands the Egyptian cavalry bolted and the square was broken with over two thousand one hundred Egyptian soldiers killed. Tyndale-Biscoe could hear the battle from Trinkitat, and the survivors struggled back into the town. The Dervishes feared the guns on the Royal Navy ships and did not advance any further.

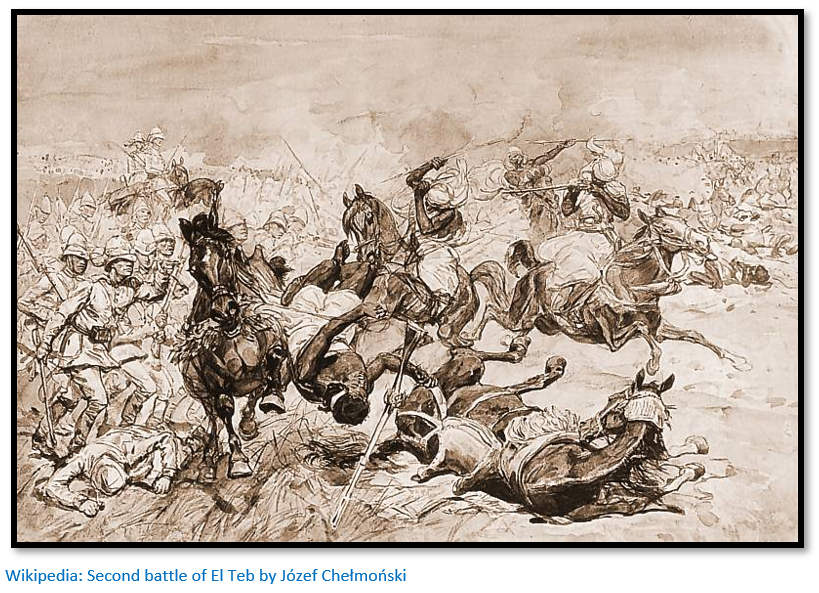

Second Battle of El Teb

Following this defeat General Graham decided the towns of Tokar and Sinkat needed to be recaptured before Suakin was retaken. By 8am on 27 February 1884 the whole British force of three thousand had been landed along with four Gatling and two Gardiner guns. Tyndale-Biscoe was in the left-hand battery in charge of one of the Gatling guns. They left Trinkitat at 6am next day and by 1pm reached the zariba[i] made previously by General Baker. The force camped outside the zariba with the horses and mules inside. They were restless throughout the night. The next day 29 February British forces advanced on the Dervishes at El Teb. Tyndale-Biscoe later wrote:

“It was about 11:20 AM when the square approached El Teb. We soon came upon the scene of Baker's defeat. It was carnage. The enemy opened fire first from entrenched positions on rising ground. Apart from musketry, we were surprised to be fired on by several Krupp guns. The latter were worked by Egyptian artillery. These guns had been captured at the Baker Pasha disaster. Their Egyptian crews were now press-ganged into working for the enemy. Our line of advance changed. Soldiers who had been marching in the columns along the flanks took up defensive positions behind Commander Rolf's men. Thus, the rear of the square became the face. During this manoeuvre, Lieutenant Frank Royds of the Carysfort was badly wounded. At great risk, Surgeon Gimlette of the Euryalus helped convey him back to Trinkitat. Sadly, the effort was in vain.

About 10,000 Dervishes suddenly rose out of the desert. Some were on horseback, others on camels. They made repeated and fanatical attempts to rush our square. Ululating from the background and shouting in the foreground helped amplify their attack. They came in dense masses, armed with spears, swords, and muskets. We mowed them down in hundreds at close quarters with our machine gun and rifle fire. I was manning a Gatling gun on the left flank. Before I ran out of ammunition, I called upon our forward men to withdraw whilst I could still give them cover. As soon as it looked as though they were safe, I immobilised my gun before making a hasty retreat myself. Luckily, the Royal Highlanders were standing in line toe to toe. They were firing regulation volleys into the enemy. Some had their skean dhu’s (dirks) at the ready for hand-to-hand combat. Unashamedly, I ran between their legs to temporary safety. At length, the enemy were driven back. No nightmare is worse than running out of ammunition in the face of a surging horde of fanatics. On this occasion, I lived to fight again, soon.”[ii]

“Captain Wilson replaced Lieutenant Royds at the right flank half-battery of machine guns. He moved from the square to attack the first of the enemy batteries. At the same moment the Arabs made a dash on a corner of the square where a detachment was dragging up one of the Gardiner’s. Wilson rushed to their defence. At once, five or six Arabs surrounded him. He became engaged in personal combat. When his sword broke, he continued to fight with his fists and sword hilt. Luckily, men from the York and Lancaster Regiments were able to intervene in time with their bayonets. Wilson had a scalp wound dressed before continuing his advance. For this piece of gallantry, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

The guns of the enemy’s first battery were captured within an hour. Major Tucker turned these upon the enemy’s second position. It was a large brick building with loop-holed walls, surrounded by rifle pits. The Naval Brigade under Lieutenant Graham soon overran this position. The village of El Teb was then cleared of enemy. The last enemy position was rushed about 2:00pm. Two Krupp guns, one Gatling, one brass gun and two rocket tubes were captured. At this point the Arabs fled, leaving behind 1,500 dead on the desert sand. Their walking wounded stumbled back with those who fled. We lost another three of our blue jackets in this encounter.[iii]

Tokar was retaken from Osman Dinga on 28 February 1884. We replaced a new Egyptian Garrison. We then undertook a strategic withdrawal back to Trinkitat on 2 March. After re-embarking onto our ships, we sailed again to a point up the coast south of Suakin. Our forces disembarked there on 9 March. The next objective was to disperse the Arabs who were beleaguering Suakin.”

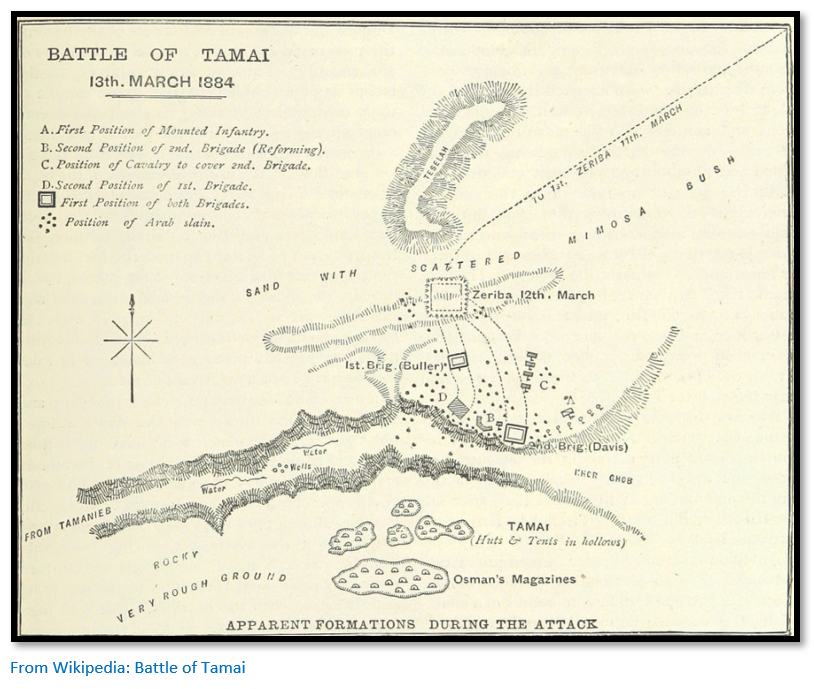

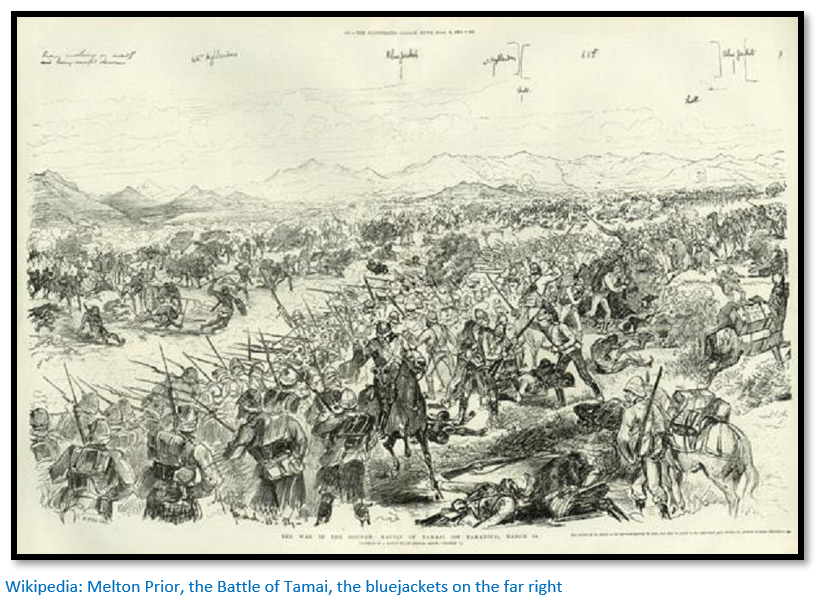

Battle of Tamai (or Tamanieh)

The battle took place on 13 March 1884 between a British force under General Graham and the Mahdist Sudanese army led by Osman Digna. Despite his earlier victory Graham knew Osman Digna’s force was far from broken and still enjoyed the support of the local population.

Accordingly, a second expedition left Suakin on 10 March in order to defeat the Mahdists. It was composed of the same units that fought at El Teb; 4,500 men with twenty-two guns and six Gatling and Gardiner guns. The Mahdists had 10,000 men, most of them belonging to Osman Digna’s Hadendos tribe, known to British soldiers as “Fuzzy Wuzzies” for their unique hairstyles.[iv]

The advance began on 11 March and that night the force camped in a zariba eight miles from Suakin. Information was received that Osman Digna’s Army was assembled in a ravine, known as Khor Ghob in front of the village of Tamai. At 8:30am next day the force again moved forward until 4pm. This time they were in two square echelons with the naval brigade in the left echelon just behind the front face of the square and in front of the reserve ammunition and baggage wagons.

On 13 March 1884 at 8:20am the advance continued with the second echelon lagging behind the first when the edge of the Khor Ghob was reached. Tyndale-Biscoe later wrote: “Arabs could be seen milling within and beyond the Khor. At this moment the enemy spied us. Dervishes made some ugly rushes towards us. We stopped them with our firepower. This was the moment. The order was given for us to charge. We had two hundred yards to cover.

The naval brigade, with its guns, and the Royal Highlanders dashed forward instantly at the double. For some reason, the York and Lancaster's tarried. We heard later that they had not been given the order to charge. They still held the front and flank of the original square. Consequently, our force was split open in two parts in the face of the enemy, exposed. We were all vulnerable. Our naval guns were soon in hot action. Smoke hung heavily over the still air. This was the moment that the enemy chose to counterattack. There was a nullah, or depression, which ran at right angles to the Khor. A mass of concealed tribesmen crept out of this and rushed upon the York and Lancaster's from behind. Chaos reigned. There was no panic on our side. It is strange how one can sometimes remain calm in moments of extreme danger. It is as if one is fighting somewhere else in a trance.

Our troops displayed great gallantry. They formed little squares and fought back-to-back. Major Cornwall mustered a larger square of 150 of his men. They made a useful stand, firing regulation volleys into the enemy. The rest of our men continued to fight but were driven about 800 yards to the left rear.[v]

“At this stage, we in the Naval Brigade had nearly run out of ammunition for our guns. The ammunition had been left behind in that part of the square that had stalled behind us. We were still at the edge of the khor. The men had to form round their useless pieces and continue desperate hand to hand combat. All three of our Navy Lieutenants and seven bluejackets were cut to pieces in front of us. Midshipman Hewett and I were left to take over command of the Naval Brigade. Once again, we performed a strategic withdrawal. We provided machine-gun cover with our last few rounds, fighting the rear-guard action as our men withdrew back behind us to the original square. We then disabled our guns ... “

Soon after the second echelon joined the battle, and its firepower swung the battle. The disbursed squares rallied back on those who had held firm. Ammunition was brought up and served out. It was not long before lost ground was recovered and all the abandoned guns except one Gatling were recovered. Tyndale-Biscoe continued:

“Our next action was to clear the Khor of all Arabs. The first brigade was able to cross. At this juncture, the remaining Arabs decided to decamp. By noon we occupied their camp and wells. We reckoned that the enemy must have lost 2,000 men killed in this second engagement. Their bodies were scattered like broken dolls over the sands and rocky outcrops of Tamai. We heard that Osman Digna himself was wounded. In this battle we lost about one hundred of our men killed and the same number were wounded…It was my job to help identify those of our men that had fallen. The task was grisly…We eventually regrouped ourselves at the coast. On the 18th we were able to re-enter Suakin itself after having cleared all the surrounding desert of enemy enclaves.”[vi] [vii]

Commended by Commander Rolfe to the Admiral for gallant conduct

Midshipmen Hewett and Tyndale-Biscoe were recommended for their great coolness and gallantry. In addition to being awarded the Egypt Medal 1882-89, Tyndale-Biscoe was also eligible for the Khedive’s Bronze Star (Egypt) and the 4th Class of the Turkish Order of Medjidie, although these last two awards were not included in a lot of his medals sold at Dix Noonan Webb on 10 December 2014 as at the end of this article.

Promotion to Acting Sub-Lieutenant

Having spent three years as midshipman on HMS Britannia, Minotaur and Euryalus Rear Admiral Sir W. Hewett recommended that Tyndale-Biscoe take examinations for Sub-Lieutenant which he duly passed with marks of 80% in seamanship and gunnery. However, he had developed a slight stammer and it was thought a spell back in Naval College would put that right.

Tyndale-Biscoe left Suakin on 25 March 1884 and after visiting Malta and seeing his family entered the Royal Naval College at Greenwich on 13 May. In December he wrote his lieutenant qualifying exams coming third overall. This was followed by a short spell on HMS Wellington at Portsmouth on torpedo and gunnery classes where he narrowly missed a first-class pass. In July 1885 he wrote examinations in navigation and piloting achieving a 75% pass.

Further sea postings and promotion to Lieutenant before retirement from the Royal Navy

Posted to HMS Neptune in the Mediterranean his Captain ordered him to write a letter requesting medical treatment for his slight stammer and he returned to England where he learnt he was promoted to Lieutenant.

With the help of a speech therapist, he cured the stammer and after being cleared by a medical board returned to sea in the sloop HMS Icarus before the year’s end. Unfortunately, it proved to be an unhappy appointment. In the two years as they cruised up and down the west coast of Africa as far as Cape Town it was becoming obvious that the captain was becoming mentally unbalanced - he punished minor offenders by hanging them by their thumbs from the yardarm. By September 1887 Tyndale-Biscoe, aware of the growing unrest in the ship’s company, decided to act and, when his captain was ashore at Accra, gathered the crew and told them their captain was suffering from a serious medical complaint - possibly caused by advanced syphilis. As a result, he informed them, he would resign his commission before reporting the matter to the Admiralty. However, the Captain pre-empted him and had Tyndale-Biscoe committed to a medical examination on account of his ongoing stammer, as a result of which he was put on the Navy retired list invalided from the service - ‘This was done more on the evidence of the Captain’s letter than upon the Surgeon’s own findings ... So, I knocked off duty.’[viii]

Recruited by the British South Africa Company in the Artillery - C Troop of the Pioneer Column

Three months later, Tyndale-Biscoe visited the London offices of the British South Africa Company, and ‘presented them with a copy of my credentials.’ Before setting sail on the Grantully Castle he spent his last night with his brother Cecil who at the time was the Curate at Whitechapel, the hunting ground of the serial killer ‘Jack the Ripper.’ Sir John Willoughby, who had resigned from the Royal Horse Guards, was a fellow passenger.

Rhodes was away at the time of his arrival in April 1890, so he was interviewed by Major Frank Johnson:

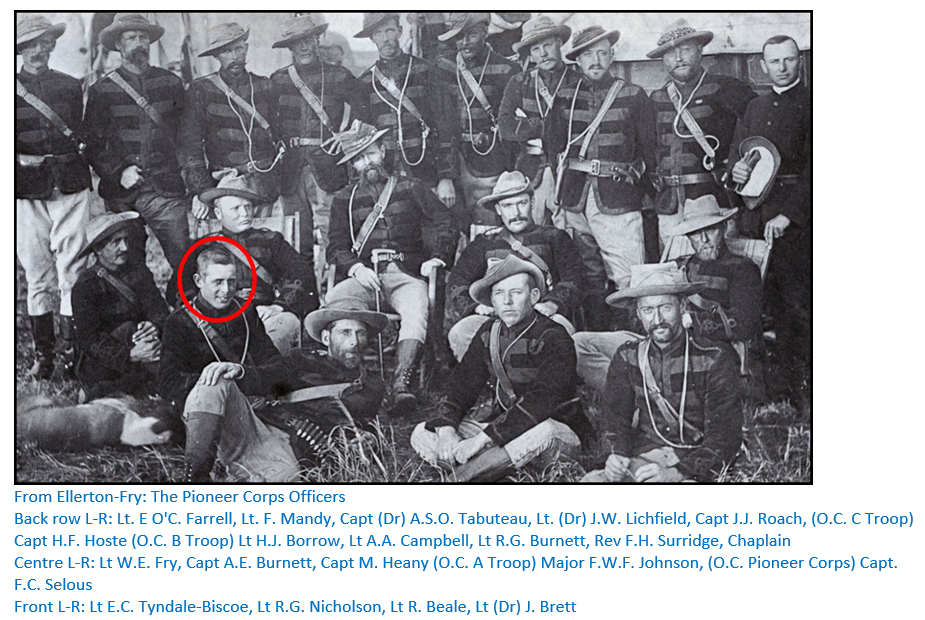

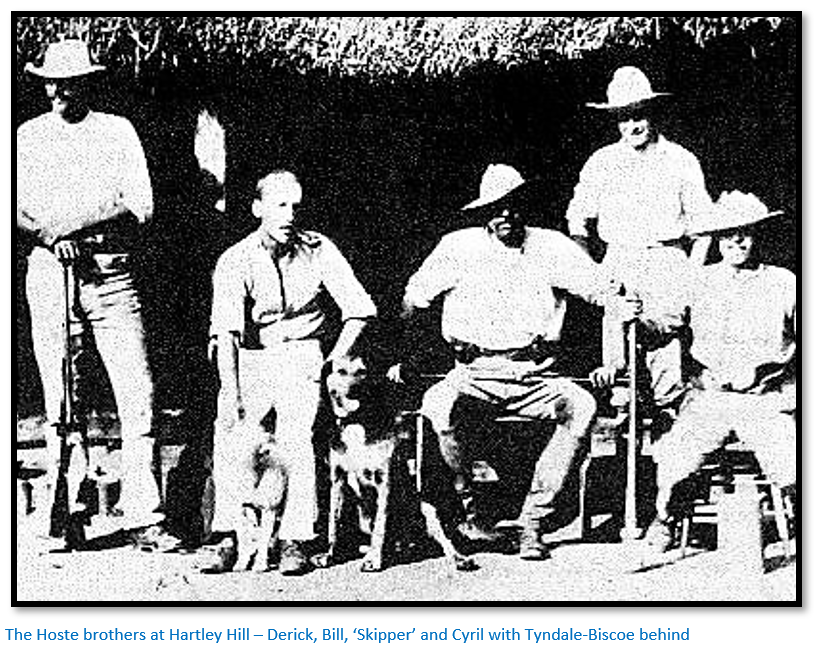

“Johnson wanted to be assured that a navy man could also have riding and shooting abilities. He already knew my credentials as a gunner at sea and on land. I was at his house at 5am the next morning, as agreed. Back in the saddle, I was soon put through my paces in every facet of horsemanship. I was then taken back to the stable to be questioned on stable management. Johnson seemed sufficiently satisfied with my prowess as a horseman to bring me down to the beach to test my shooting abilities as well. There were six other potential officers on trial including Captain ‘Skipper’ Hoste and Sir John Willoughby. Captain Hoste had been Commodore of the Union Company and had commanded the "Trojan." This was the ship on which Cecil Rhodes had chosen him to take part in the occupation of Mashonaland. We shot at bottles, sometimes swinging, from varying distances and angles. We tested ourselves with rifles and pistols. My experience in deer stalking and shooting driven partridges had honed my marksmanship pretty well. Soon after that, Major Johnson signed on only two of us as members of his pioneer column. Part of his strategy must have been to see how we related to each other. Skipper Hoste was given B Troop to command. I was enrolled as Lieutenant (R.N. retired) under Captain Roach in C Troop. He and I would be in charge of the artillery.”[ix]

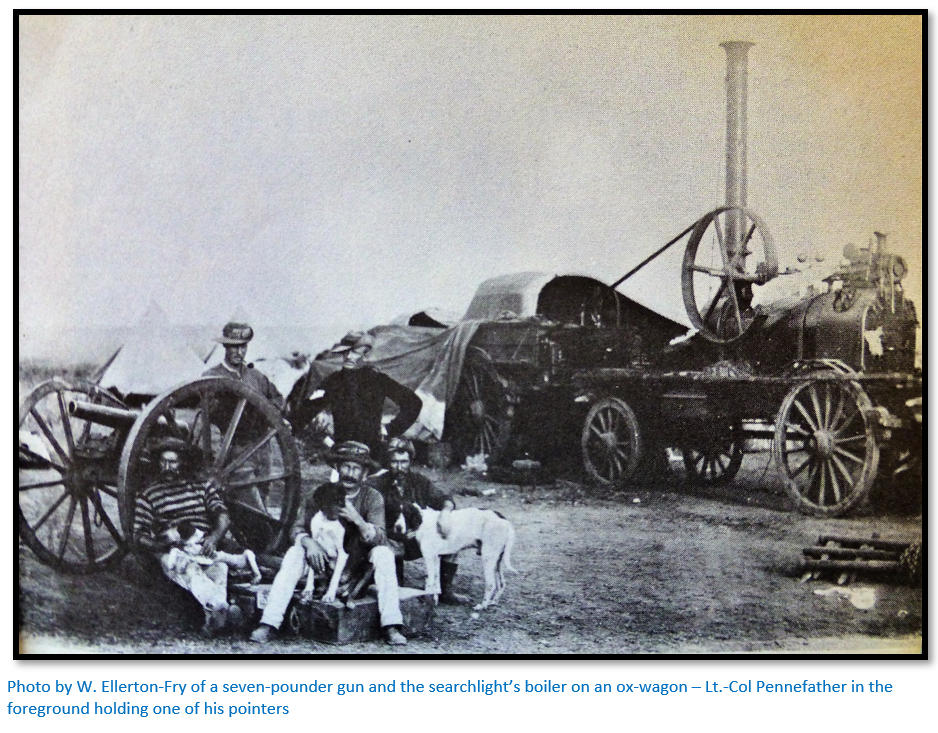

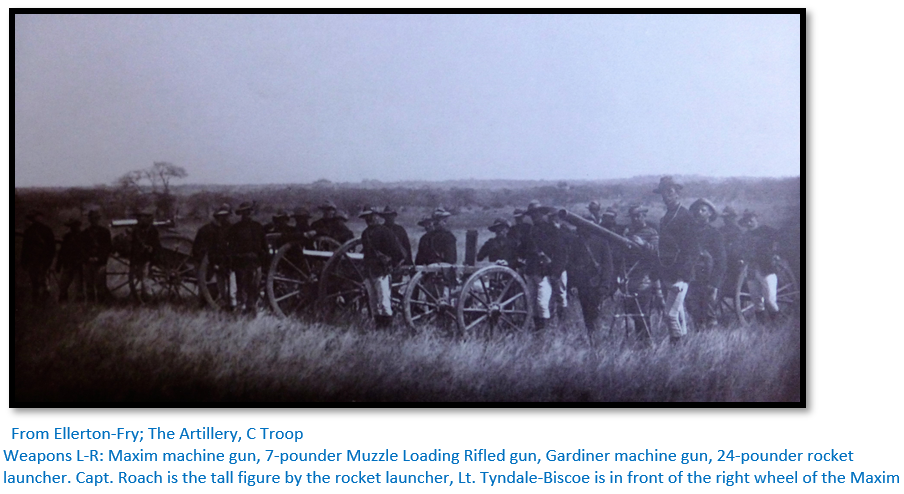

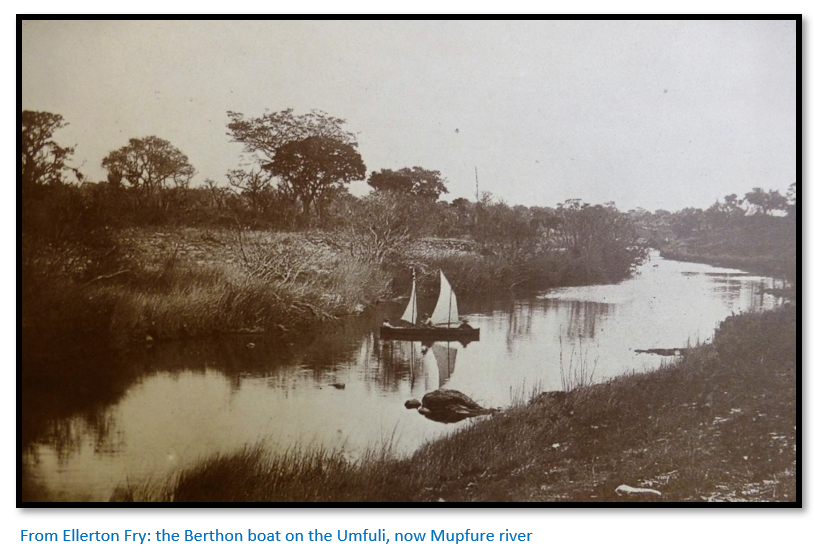

Admiral Nicholson handed over a Berthon collapsible boat [There is a photograph by Ellerton-Fry of ‘Skipper’ Hoste, Tyndale-Biscoe and Ivon Fry sailing the Berthon on a pool of the Umfuli, now Mupfure river in the article The Pioneer Column’s march from Macloutsie to Mashonaland under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] They had some 24-pounder rocket tubes, a Gatling and Gardiner gun and a Navy searchlight. Johnson had already ordered a sixteen horsepower Ruston Proctor engine and dynamo from England to power the searchlight.

The Pioneer Column also took two RML (Rifled Muzzle-Loading) 7-pounder field guns that Tyndale-Biscoe had to check before acceptance and he also collected the five bluejackets that had volunteered to form the nucleus of the artillery troop. On the 15 April 1890 thirty recruits of the Pioneer Corps left Cape Town by train for Kimberley which was reached two days later.

The march from Kimberley

Tyndale-Biscoe describes Kimberley as “a wretched town, comprising mostly corrugated iron. We heard that Captain Jack Roche, the prospective leader of our artillery troop, had already lost nineteen of his horses to horse-sickness at his advanced post. The next day no less than 50 of us assembled outside the Kimberley club. Another 20 men had joined us. There our gear was repacked into three wagons. The Governor, Rhodes and an Admiral Wells strolled outside to see us off. The Governor insisted on making a speech. Skipper Hoste and Borrow were to stay behind for further briefing. For that reason, I was placed in charge of the vanguard detachment. We left at 4:30 pm. It was the start of our trip of 360 kms (225 miles) to Mafeking.”[x]

Gradually the various detachments arrived: “In the Interlude, I was given the task of training prospective horsemen, while Borrow put the awkward squad through its paces. We even had time for a game of cricket…On 16 May our horses did arrive under the charge of Lieutenant George Burnett. Lieutenant Farrell accompanied him. He was the veterinary officer. Needless to say, the horses arrived in prime condition. At that stage, we had twelve officers and 90 other ranks. There were enough horses for each man to be issued with two animals. The second became a lead horse.”[xi]

Tyndale-Biscoe describes a typical day’s travel: “The 2am Reveille sounded. The night became alive with yelling and cracking of whips. The last wagon moved out after an hour. Those of us who had horses rolled ourselves up in our overcoats again and slept on until daybreak. Fires crackled away the small hours. At the sound of ‘boots and saddles’ at 5am we fell in, then moved off. We re-joined the wagons just as they were outspanning at mid-morning. At the sound of ‘stables’ we proceeded to groom our horses before turning them out to graze under a mounted horse-guard of four men. At 3pm the convoy continued the second half-day journey. We outspanned once more about 8:30pm. In this fashion we were able to average about twenty-five miles a day.”

The process was repeated each day using the cooler hours of night to spare the oxen. The nights were cloudless and often frosty. On 6 May they reached Mafeking, now Mahikeng, where Colonel Sir Frederick Carrington, commanding officer of the Bechuana Border Police recommended a camp site next to the Molopo river. After leaving Gaborone they spent a few days journeying along the banks of the Crocodile river, which then changed its name to the Limpopo river. The nights were freezing, and they arrived at Camp Cecil on 31 May 1890. The Camp lay on the north bank of the Limpopo river in Khama’s territory and here firearms were issued to all the men (a six-chamber Webley revolver, Martini-Henri rifle, and bandolier with a hundred rounds of ammunition and a hand axe) and the officers received their commissions from Sir Henry Loch.

The artillery - C Troop

Captain Roach the commanding officer is described as tall and lanky with a Yankee drawl. There were thirty-four men in the Troop and apart from the Royal Navy bluejackets there were a number of others who served in the Cape Field Artillery, so they were all gunners or bombardiers.

The march to Salisbury

Author’s note – David Tyndale-Biscoe seems to have taken most of his details of the journey from ‘Skipper’ Hoste’s book Gold Fever. Perhaps Tyndale-Biscoe was too occupied as two i/c with his responsibilities to make detailed notes in his diary. These details are well covered in the two articles:

- The Pioneer Column’s march detailed on maps

- The Pioneer Column’s march from Macloutsie to Mashonaland

Both are included under Harare Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Tyndale-Biscoe featured in a number of incidents on the march into Mashonaland. The inspection by General Methuen was over and the Pioneer Column had just broken up their camp on the Macloutsie:

… “The next day we had a visit from a Transvaal Boer, Frikky Greeff. We had been warned that he was coming to spy out our strength in the interest of some Transvaal filibusters who were keen to thwart our plans. We were quite prepared to see him, we had nothing to be ashamed of, so we made him a welcome guest and showed him everything.

In the evening after dinner, we had a buck sail with a bulls-eye marked on it hung to a couple of trees about two hundred yards away from the electric searchlight whose beam we then turned on the target.

First of all eight of our best shots fired at it. Although it was not easy to mark the shots properly it was easy to see where the heavy Martini bullets struck by the vivid light given by the searchlight. That impressed Frikky considerably.

Then Biscoe, who was something of an artist with the Maxim gun, got that going. He made patterns all over the target and finished up by writing his name right across it.

Finally, the seven-pounder was fired at it and the whole contraption swept away. ‘Allemagtig’ exclaimed Frikky, ‘that’s not fighting, that’s murder.”[xii]

This scene described in Sailor Soldier is almost identical to that in Gold Fever: “…we had three rivers to cross in quick succession. They were the Bubiana river, the Bubye River and the Umjinge river. It was on the last crossing that the wagon carrying the sixteen horsepower Ruston Proctor steam engine overturned. It was going down the steep embankment. The hind oxen were fatally injured. It was still early morning when I arrived on the scene. Johnson was staring woefully at the wreckage. I had the naval brigade with me. We reassured the Major that we could right it, given the rest of the day. We cut down some tall trees for sheerlegs. These we rested on a foundation comprising hundreds of sandbags. At the tripod we dangled the block and tackle. The river was too deep to use oxen, so we hauled the wagon off the riverbed with naked manpower. Gradually we were able to turn it back onto its wheels. The only damage was a slight crack in the smokestack. Before darkness, the wagon had resumed its place in the laager. We soon had the engine working again and the searchlight doing its protective probing of the surrounding bush.”[xiii]

Another incident:

… “While on the Umfuli [now Mupfure] river we found a pool of deep water just below the drift. It must have been half a mile long. It was an opportunity to try out the Berthon boat that we had portaged all this way from Simon's Bay. I joined Hoste and Ivan Fry in the boat. It sailed beautifully up and down the pool, much to the astonishment of some staring Mashonas who had pitched up. One of their headmen was called Mugabe. They had never seen a boat in their lives.”

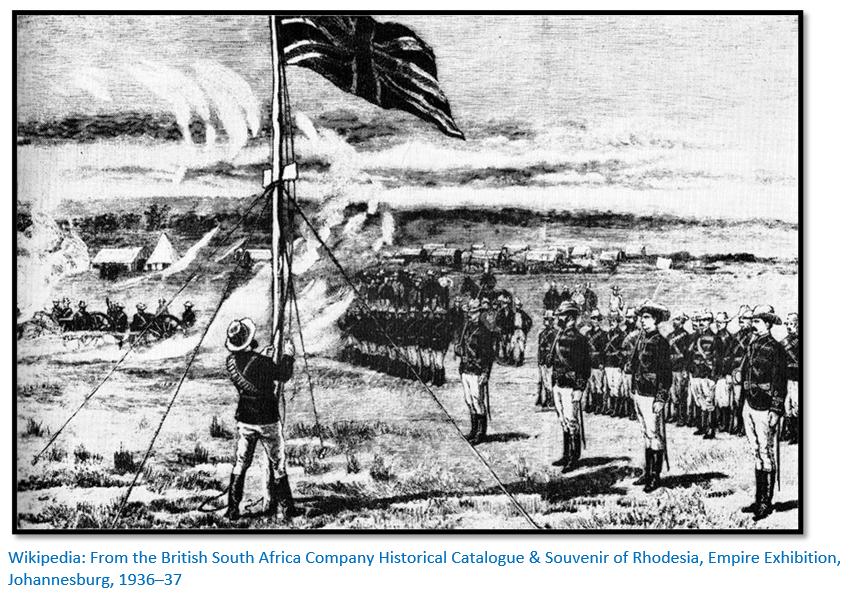

Raising of the Union Jack at Fort Salisbury

Here, then, the chapter in which Edward Tyndale-Biscoe raises the Union Jack at Fort Salisbury on 13 September 1890 - afterwards the site of Cecil Rhodes Square, Salisbury, Rhodesia. In his own words:

“Before he departed, Major Johnson issued an order that the Column would parade next day, Saturday 13 September, in full dress at 10:00 hours. Our seven-pounder guns were to fire a Royal Salute to celebrate the occasion as soon as the British Flag had been hoisted. He had given me the honour of actually raising the flag. Being a naval man, there was no danger of the Union Jack being raised upside down! In the dawn I took members of my brigade to find the straightest pole we could find from the surrounding Msasa trees. Most branches were crooked, distorted by veldt fires. Skipper Hoste, in his enthusiasm, insisted on joining us in his new capacity as parade commander for that day. It did not take us too long to find a suitable pole. We rigged halyards and stays as we erected it in the middle of the site chosen for the fort. From thenceforth the site was known as Cecil Square. A smart long straight flagpole now marks the spot. At 10:00 hours, the men paraded in front of our rough flagpole. In the centre were A and B troops of the Pioneer Column. On the right was C troop with two seven-pounder guns at the ready. B troop of the Police paraded on the left. With me at the base of the flagstaff stood Colonel Pennefather, commander of the B.S.A. Police force. With him were his A.D.C., Sidney Shepstone and Sir John Willoughby, the B.S.A.P. second in command. I stood there at attention with the flag rolled up under my arm while Canon Balfour gave a short address and an extempore prayer of thanks for our deliverance. His cassock billowed in the breeze. As he concluded the prayer, the bugles sounded "The Royal Salute." The parade presented arms while I slowly raised the furled Union Jack to the top of the mast. As I struck the flag, it unfurled itself into the breeze and my Naval Brigade fired a twenty-one-gun salute. When the echoes of the last shot died away, the Colonel called for three cheers for Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria. The parade responded lustily. I was able to wave my naval sword instead of my hat! Mashonaland became part of the British Empire. We now had to defend and nurture it with an economy that would free the tribesmen from ignorance and poverty and provide paid work opportunities for everyone, including the Matabele. It was an emotional moment.”[xiv]

Not yet civilians

The raising of the flag ceremony did not mean their contracts were over. The fort still needed building and the work was carried out in three hour shifts with A Troop starting, followed by B and then C Troop and finally the wagon-drivers working as a team.

Tyndale-Biscoe says they were plagued by packs of dogs – at least a hundred mongrels who often attempted to share a bed at night. “We slept on the ground in our tents, so it was easy. Often, just as sleep beckoned, the intruder would gallop outside one’s tent in a great scurry and proceed to bark as if its life depended on it. This had a domino effect. Other dogs preceded to bark from every quarter. The noise would reach a crescendo. As the cacophony died, so the intruder would return, only to belt out again after a few minutes when another dog decided to set off a new tumult.”[xv]

I handed the guns and searchlight over to the BSAC Police on 27 September 1890 and purchased two horses, in readiness for the disbandment of the Pioneer Column. Fort Salisbury was nearly finished and to celebrate the event their Regimental Sergeant Major William Fleming King and other ranks put on the play “Knock About Farce” which was much enjoyed by their audience.

On Tuesday 30 September 1890: “Major Johnson stood on a wagon to make his final eulogy to the parade. We were all standing at attention in our ranks. He then gave us the command to ‘Ground arms,’ then ‘Right turn.’ At ‘Dismiss’ the men saluted and broke away. It was the first time in British history that a country’s civil population had been created by a word of command.”[xvi]

A civilian prospector in the Mazoe Valley

Like the majority of the Pioneer Corps members Tyndale-Biscoe formed a prospecting syndicate. His syndicate included ‘Skipper’ and Derick Hoste, and they set up their headquarters near the kopje and whilst Derick went off to Hartley Hills, ‘Skipper’ and Edward began prospecting for gold in the Mazoe area. Sir John Willoughby also joined their syndicate contributing a wagon and tools before leaving on a visit to England.

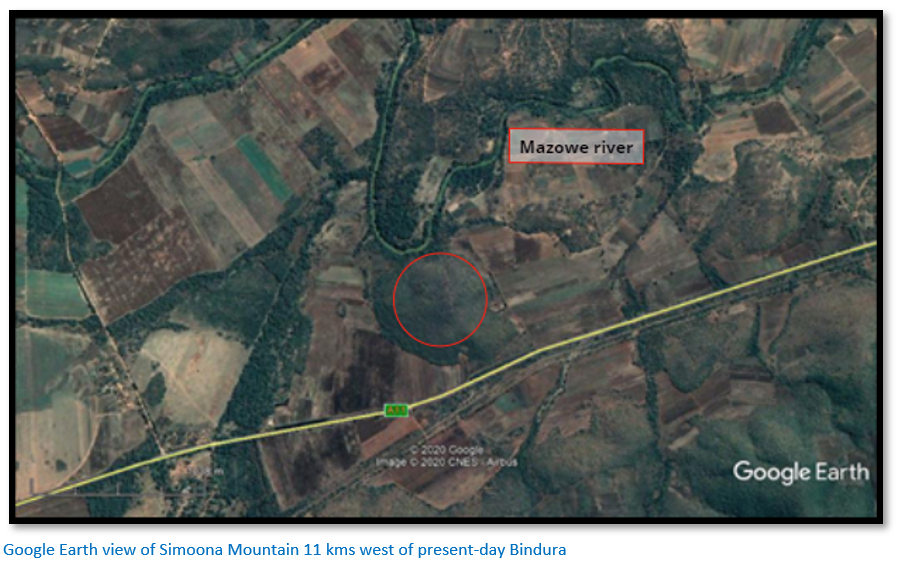

At Mazoe they were joined by the Burnett brothers and an ex-BSAC Policeman called Bowen (his name is not listed as such on the records) and gloomy at finding no payable gold they asked some passing Mashona for any hints. They told them of pre-European gold workings at Simoona further down the Mazoe Valley and Ted Burnett and Bowen were sent to investigate and came back with promising quartz samples.

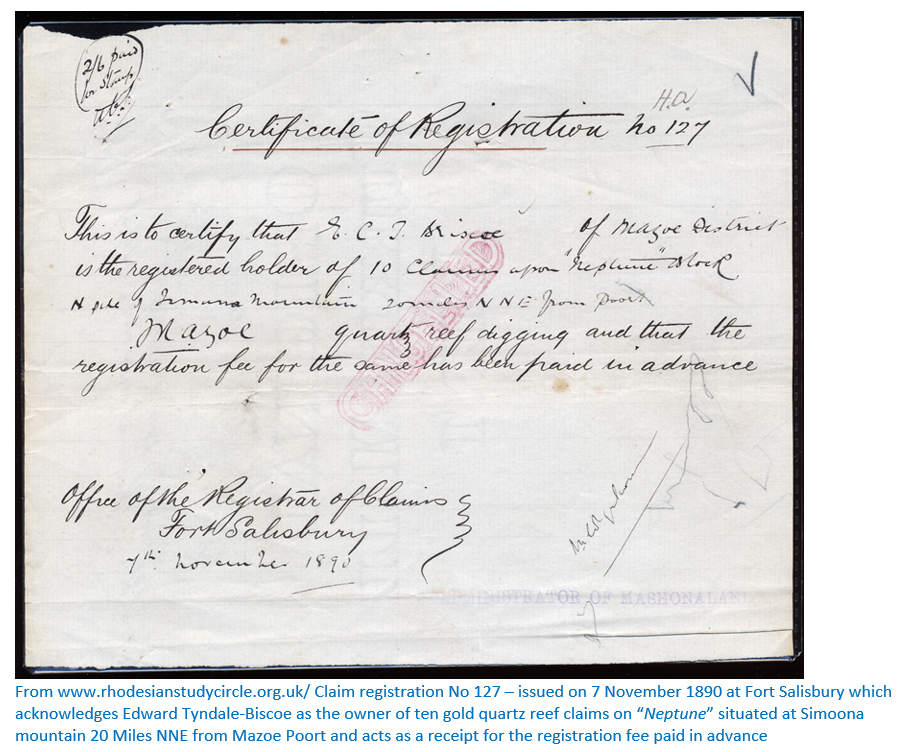

The group then trekked to Simoona and as the quartz reef showed visible gold decided to set up camp which was nearly complete when Henry Borrow turned up with a message that Derick Hoste had located some promising quartz reefs. Everyone then left for Hartley Hills, except Tyndale-Biscoe who stayed at Simoona Mountain. The gold claims above registered by Tyndale-Biscoe on 7 November 1890 are for Simoona Mountain.

‘Rocky Mountain Jack’ who features in J. Percy FitzPatrick’s Jock of the Bushveld was also prospecting on Simoona Mountain at this time. When Tyndale-Biscoe returned to Salisbury for supplies he heard the others had pegged claims at Hartley Hills and that the Administrator A.R. Colquhoun had given ‘Skipper’ Hoste a commission for us both to assist Captain Forbes in his dealings with Chief Mutasa in Manicaland who was playing off the Portuguese and the BSA Company against each other.

They were leaving the following week, so they visited Simoona where five claims were named the “Trojan” reef after Hoste’s last ship and this too was registered on 7 November 1890.[xvii]

Manicaland and the Portuguese

The story of how Forbes with a small band of BSACo Police managed to overpower the Portuguese is described in detail in the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

The Administrator of Mashonaland Colquhoun had signed a treaty with Chief Mutasa on 14 September giving the BSACo exclusive prospecting and mining and infrastructure development rights in Mutasa’s territory and the chief also agreed: “not to enter into any treaty or alliance with any other person, Company, or State, or to grant any concession of land without the consent of the Company in writing, it being understood that this Covenant shall be considered in the light of a treaty or alliance between the said nation and the Government of Her Britannic Majesty Queen Victoria.”

Colquhoun subsequently sent Selous and two police troopers to Fort Massi-Kessi (Macequece) where they received a cool reception from Baron de Rezende of the Companhia de Moçambique and were informed that the party with its police troopers had been on Portuguese territory and illegally signed a treaty with Chief Mutasa who was subordinate to Chief Gungunhana in Gazaland and was therefore not free to sign treaties. Baron de Rezende’s written protest was rejected by Colquhoun before he left for Salisbury leaving police trooper Trevor at Chief Mutasa’s kraal.

The news of the treaty had considerably annoyed the Portuguese and tension began to escalate in the region. The Governor of the province of Gorongosa, a Goanese named Manuel Antonio de Souza ‘Gouveia’ and Col. Paiva de Andrada had arrived with two hundred armed natives at Chief Mutasa’s kraal to force him to change his allegiance. Gouveia had past form at terrorising local chiefs and coercing them into submitting to Portuguese rule.

On 15 November 1890, Andrada held an indaba at Chief Mutasa’s kraal at which the Chief was persuaded to renege on his recent treaty concession with the BSACo. Local prospectors at Penhalonga; Messrs Harrison, Harrington, Harris, Campion, Moodie and Maritz were summoned to Bingaguru Mountain to witness Chief Mutasa swearing allegiance to Portugal.

The action in which Forbes, Hoste, Eustice Fiennes, Fleming King and Tyndale-Biscoe together with a small number of police troopers successfully outwitted and managed to arrest Gouveia and Andrada is told in the above-mentioned article. The surrender of Fort Massi Kessi and Forbes’ subsequent attempt to march on Beira was ended by the arrival of Sir Henry Loch’s aide-de-camp, Major Sapte - it being feared such actions would trigger an international incident owing to existing Portuguese interests.

Whilst based at Massi-Kessi Tyndale-Biscoe explored the numerous ancient gold workings and saw evidence of alluvial workings before returning across ‘the Divide’ to Fort Hill where ‘Skipper’ Hoste and he were joined by Derick Hoste where they had plum pudding with the BSACo Police officers on 25 December 1890. [See the article Fort Hill – the first site of Umtali, now Mutare under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

They stayed in the huts on the side of Sabi Ophir Hill about half a mile from Fort Hill which were built for the first three trained nurses in the country [See the article Nurses Memorial under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

On Boxing Day, they commenced the long journey back to the police camp at Salisbury, a difficult journey owing to exceptionally heavy rainfall, the horses and oxen needed to be swum across the swollen Odzi river and everyone in the party came down with malaria. It took six weeks to reach Marandellas and they found the two men at Rusape “haggard and yellow from fever.” The rain gauge at the police camp by early April registered 137 cms (54 inches) of rain.[xviii]

The Battle of Chua Hills in 1891 and prospecting in the Lomagundi, now Makonde district

In May 1891 was fought the Battle of Chua Hills at Massi Kessi (Macequece) which is described in detail in the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese and during which Tyndale-Biscoe used the captured field gun to great effect against the Portuguese troops.

Clearly this all distracted from their prospecting efforts and in June their syndicate directed its efforts at the Lomagundi district or “northern goldfields.” Derick now joined by his brothers’ Cyril and Bill and a friend Max Lambert set off for the Umvukwes mountains. ‘Skipper’ and Tyndale-Biscoe had to help free their wagon from a swamp before the party arrived at their gold reef claims, “St Valentine” and “Blue Peter” and they built a camp on a nearby hill.

Jackals and hyenas disturbed their sleep; one night when Tyndale-Biscoe could not sleep he tapped out the ashes of his pipe on his wagon and next moment there was pandemonium. The hot ashes had fallen on a lion under the wagon who roared his displeasure and took off for the nearest bush like the scalded cat that he was! The same lion returned on three subsequent nights until Tyndale-Biscoe fired a shot at him and he did not return again.

Both of the quartz reefs on their claims soon petered out and most caught malaria with Max Lambert the worst affected. He was sent into Salisbury by scotch cart, but Mother Patrick told them he died soon after arriving. [See the article Mother Patrick’s Mortuary under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

News arrived of the death of Tyndale-Biscoe’s mother and he decided to return to England. It was the dry season and Tyndale-Biscoe and his manservant Charley left on 5 August on foot arriving at Marandellas, now Marondera, two days later. Four days later they were at the bottom of the Devil’s Pass [See the article Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] where a lion prowled around their camp.

On 13 August they had breakfast with Lt-Col Pennefather who gave them supplies and porters for the onward trip. It took two days to reach Macequece where the porters refused to go further, but he managed to hire new porters as far as Gondola where they hitched a ride on wagons belonging to the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow. By 20 August they had reached the Ponte do Pungwe, or Fontesvilla where canoes were hired to take them down the Pungwe river; Beira was reached on 23 August and Tyndale-Biscoe departed on the ‘Magician.’

Return to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe in 1892

Tyndale-Biscoe returned to Cape Town in March 1892 and met ‘Skipper’ Hoste where he discovered that the pessimism brought about by Lord Randolph Churchill’s articles regarding any future El Dorado in Mashonaland had choked off the supply of capital to all the potential mining companies. [See the article Lord Randolph Churchill’s visit to Rhodesia in 1891 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] However he and Skipper decided to return to Mashonaland taking RMS Africa to Beira and then walking overland via Umtali to Salisbury.

They found that Derick, Cyril, and Bill had gone to manage the ‘Bonanza’ claims on the banks of the Umfuli, now Mupfure river at Hartley Hills. The five-stamp battery had originally belonged to Lobengula and been in the charge of James Dawson but had since been abandoned. The syndicate worked their claim for 36 days and on cleaning up the concentrate found they had 30 oz (550 pennyweights) of gold from the 220 tonnes of quartz crushed – a low result of 2.5 pennyweights per tonne. The quartz reefs on the ‘Bonanza’ like so many others had simply petered out.

For a year after the Pioneer Column stood down, none of the surveyed farms were distributed as the Rudd Concession only gave the BSACo mining rights. It was only after the Lippert Concession had been purchased by the BSACo that farms were allocated to the Pioneers. This topic is explained in detail in the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

In the meantime, the Hoste / Tyndale-Biscoe syndicate decided to sell their land rights to the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow to raise cash for their mining operations – they and most of the members of the Poneer Corps clearly had no intention of farming and did the same.

It was now October and the rainy season had started which put a stop to mining, so they all packed up and left for Salisbury where Tyndale-Biscoe took up an appointment as Clerk of the Court.

In February 1893 Derick Hoste went back to Hartley Hills to go prospecting again. A few months later he found the Mining Commissioner very ill with malaria and nursed him back to health, but then went down with blackwater fever himself and died on 25 May 1893 – an article the story behind Derick Hoste who died of blackwater fever at Hartley Hills in 1893 is under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Cyril Hoste and Tyndale-Biscoe returned to Simoona mountain to work on their gold claims until the clashes with the amaNdebele broke out in late March 1893. The background and detail of the Matabele War of 1893 are included in the article Iron Mine Hill (Ntabasinsimbe) and the first casualty of the 1893 Matabele War under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

Matabeleland 1893 - the ‘galloping Maxim’

With the build-up of tensions with the amaNdebele to October 1893, Tyndale-Biscoe returned to uniform, being appointed a Lieutenant in ‘A’ Troop of the Salisbury Horse in charge of the Nordenfeldt and Gardiner guns. Each volunteer was to be rewarded with six thousand acres of land in Matabeleland, twenty gold claims and an equal share of half the cattle captured.

The campaign to invade Matabeleland underway, the Salisbury column linked up with Major Alan Wilson’s column at Iron Mine Hill and saw action against the amaNdebele at Shangani and Bembesi. Ted Burnett, one of the originals in their mining syndicate was killed on the 24 October when he looked into a hut thinking it was empty and was shot in the chest. There is not much information on the battle of Shangani (called Bonko by the amaNdebele) which began pre-dawn on 25 October 1893. For a detailed account of the battle see the article Battle of Shangani (called Bonko by the amaNdebele) under Matabeland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

Battle of Shangani called Bonko by the amaNdebele

Tyndale-Biscoe wrote: “Shortly before dawn, three Mashonas with our column went to the river for water. A dozen Matabele warriors with knobkerries and assegais attacked them. Two Mashona were killed, but the third escaped to give us the alarm. The laagers were aroused, and the men were at their posts immediately. In the uncertain light the main body of Matabele attacked the kraals occupied by our staff. The concourse of men surrounding our laagers therefore comprised Matabele and friendlies. When our Maxim's opened fire, both suffered. The Matabele charged with reckless gallantry. By ‘Rooidag’[xix] the dead lay thickly on the edges of the clearing. The Matabele courage wavered. They then abandoned the attack and dispersed into the bushveld. Our casualties comprised only six men wounded, and one killed.

Soon afterwards the Matabele made another audacious attack. Nearly 300 of them advanced down a slope in full view of our wagon laagers. Major Forbes was momentarily fooled by their boldness. Consequently, the impi’s were allowed to come close and open fire on us. Our returning fire was devastating. Their dash for cover was less dignified. It transpired that they were the Insukameni Regiment amongst Lobengula’s best fighting men.”[xx]

Battle of Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele)

Tyndale-Biscoe particularly distinguishing himself on a Maxim at this action:

“As soon as the Matabele attacked, the guards rounded up our oxen and horses. They were grazing on the veldt close by. The oxen gave no trouble, but the horses were terrified by the gunfire. They were brought into the Victorian laager. It was shielded from the enemy by our own laager. Before the guards could secure the horses, they started to lunge and rear. Then they managed to charge out of the laager in an avalanche of flowing manes and galloping hooves. More than two hundred galloped down the slope towards the enemy lines. If they were killed or captured, the columns were doomed. Without horses we would be immobilised. The Matabele would be free to wrought terrible vengeance on the helpless Mashona population. For a moment officers and men were frozen in horror as warriors ran out of the bushes to guide the horses to their destruction. At that moment, Sir John Willoughby and Captain Borrow jumped onto the backs of two picket horses tethered nearby. They raced towards the head of the stampede. One of the grazing guardsmen, Trooper Naylor, had pluckily stuck to his charges and was vainly trying to turn them. The two officers soon joined him. They rode under heavy fire from the exultant Matabele. They could not possibly reach the head of the stream of horses in time to save the day.

More Matabele ran from the bush to foil them. At that stage, I managed to bring the Maxim machine-gun into action. I crouched outside the laager with no cover. It was like old times. I aimed a stream of bullets between the horses and the triumphant Matabele. I had to be accurate. I gambled on plumes of dust being thrown upwards to form a dust screen. They did. The warriors leapt back on their side of the dust barrier into safety. The horses veered away on their side. I played the gun so that the horses would be herded back towards us. Sir John Willoughby and his companions were able to catch up with the leading horses and brought them all back in a wide circle into safer country into the valley behind the Victorian laager. During their mad ride they were under constant fire. Miraculously not a man was hit, neither did a horse stumble. Disaster had been averted by the grace of God. We were able to share a prayer and a drink together after the battle. Dr Jameson joined us. He was a much-relieved man. Our B.S.A.P. Sergeant-Major later had my Maxim gun photographed for posterity.”[xxi]

A detailed article called Battle of Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele) is under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

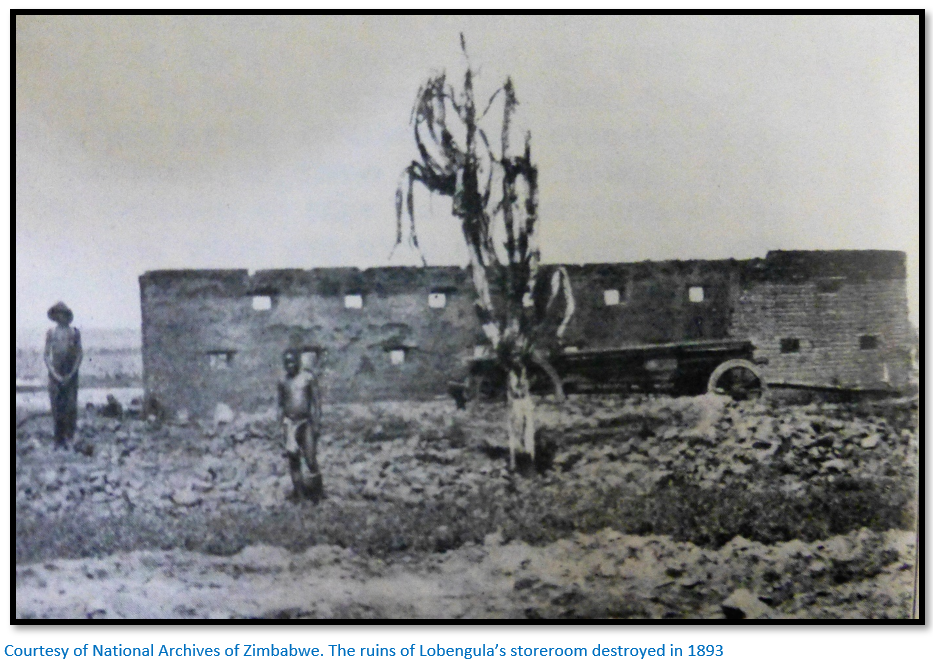

“On the morning of November 3rd our long cavalcade approached Lobengula’s kraal creating clouds of dust. As we approached, there was a loud explosion. A mushroom of smoke billowed into the sky. Lobengula had arranged to blow up his whole kraal at our approach. He had already made his escape northwards a few days beforehand. His wagons and local impis went with him. He was hoping to meet up with his spare regiments returning from their raids beyond the Zambezi River.”[xxii]

Bulawayo was entered on 4 November 1893: “led by a former Pipe Major of the Royal Scots playing his bagpipes.”

Civilian life again

The Matabeleland campaign concluded, Cyril Hoste went back to England and Skipper, Bill and Tyndale-Biscoe worked the Vesuvius Mine in the Mazoe Valley. However, the BSACo mining regulations forbade any private working of gold claims, a company had to be formed with fifty percent of the shares issued to the BSACo. This and the lack of transport to import mining machinery greatly inhibited progress.

In response they changed the focus of their prospecting efforts and joined an expedition led by Dr JA Moloney on behalf of Rhodesia Concessions Ltd to locate land north of the Zambesi to construct a light railway under a concession that also granted land and mineral rights. As a syndicate they pegged a large area of land in the Luangwa Valley in Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia.

1894 and 1895

In both years there were bad droughts in the country and the harvests failed. Then the meagre remains of the harvests were destroyed by locusts. On top of these calamities, the rinderpest struck and the cattle, European and African, died in thousands. Wagons had to be abandoned when the oxen died and all transport into the country stopped. An article entitled Rinderpest is included under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

On the 29 December 1895 Jameson took the bulk of the country’s police force on his infamous raid into the Transvaal which Tyndale-Biscoe thought was ill-conceived from every aspect. He does not disapprove of the action; just states that it was premature!

Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona (First Chimurenga) Rebellions 1896 - 7

Following Jameson’s disastrous raid of December 1895 the amaNdebele rose in rebellion in March 1896. Tyndale-Biscoe was quickly back in harness as a Captain in the Salisbury Horse, accompanying the force under Colonel Beal and including Rhodes which rushed to the aid of beleaguered Bulawayo. See the article 1896 Rebellion Memorials under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Later still, in Major White’s force, and once more in charge of the machine guns, Tyndale-Biscoe distinguished himself in the fighting around Hartley Hills in Mashonaland. In his own words:

“The arrival of the Imperial troops in Matabeleland released us in the volunteer forces to return to operate from Salisbury. As soon as we arrived in mid July 1896, our first assignment was to relieve those in peril in the Hartley district. Our patrol numbered two hundred men under the command of Major White. Once again, I was put in charge of the guns. We had three fights on the way. The rebels had fortified some hills near the road. We attacked these and must have eventually killed about one hundred and fifty of the enemy. Our losses were minimal. One member of our patrol was killed and three were wounded. We also lost some of our horses. As we travelled, we came across the remains of two white miners who had been murdered on the road. They had been attempting to summon help from Salisbury. We were surprised to find ten men were still alive when we reached Hartley. They had built a fort on a granite hill. Five hundred rebels were camped close by, waiting in siege. Our Maxim machine-guns inflicted great mortality upon them. A few managed to scatter. The siege was duly raised.”[xxiii]

The siege of Fort Hill and the actions at Fort Martin and Chief Mashayamombe’s stronghold are described in the articles Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield and Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

On 7 August 1896 Tyndale-Biscoe joined ‘Skipper’ Hoste’s patrol down the Mazoe Valley: “We knew the country like the palms of our hands. We had 150 mounted men and 50 black Rifleman. The rebels had dug trenches across our road. We merely skirted these. The rebels were in hiding in the granite hills. They were full of caves. I shelled the hills and the men stormed in behind my shellfire. We captured cattle and burnt many kraals. Two of our men were wounded. It was a typical skirmish.”[xxiv]

Mashonaland 1897

Attached to the British South Africa Police in 1897-98, Tyndale-Biscoe saw further action and befriended Lt-Col Robert Baden-Powell:

“The Mashona Rebellion had lasted sixteen months. The white civilians killed amounted to three hundred and twenty-seven, and one hundred and twenty-seven wounded. These casualties represented one tenth of the White population. Over three hundred of our militia had been killed. The rebel casualties must have measured thousands.

I had been living the life of a soldier in both Matabeleland and Mashonaland for nearly two continuous years. Sleeping on the ground with rifle at my side and awakening for the pre-dawn "Stand to" became a way of life. The forming of laagers and setting of guards were routine. I learnt how important it was to prepare every man in a patrol before delivering an attack. I used ground models of the terrain to illustrate the movements that had to take place. This was a graphical way of explaining strategy and inviting opinion. Every man had to know his whereabouts in the bush and exactly what was expected of him. Getting lost was a crime. Without a compass, a lost man tended to walk in circles. He became a liability. Being able to track spoor was vital. Ambushes were common on both sides. The crashing of our seven-pounder and the stutter of our Maxims set my ears ringing thereafter, indistinguishable from the screeching of Christmas beetles in the Msasa trees. I don't think it is normally possible to be in the saddle for so long, or to endure such hunger and thirst on occasion, trying to read where rebels were going or already hiding. In such conditions, one develops a sixth sense. One has to.”[xxv]

Civilian life prospecting once again

Following the end of hostilities, Tyndale-Biscoe returned to his gold prospecting and mining ventures in the Mazoe area with ‘Skipper’ Hoste spurred on by rumours the BSACo was reducing its claim on the ownership of any mining company from fifty to thirty percent, plus the fact that the rail connection from Beira to Salisbury was completed by 23 May 1899 thus facilitating the import of mining machinery.

They pegged the Phoenix Prince Mine on 1 November 1899 and worked it with some success providing the partners with a good income for many years. The adjacent Freda Rebecca Mine is still being worked to this day.

The defence of Ladysmith in the 1899-1902 Anglo-Boer War with the bluejackets

When the Anglo-Boer War broke out in October 1899 Tyndale-Biscoe handed over his possessions to ‘Skipper’ Hoste before leaving for Durban to offer his services to the Naval Brigade.

“We arrived in Ladysmith about 18:30 pm. I managed to find a bed in the Railway Hotel. However, I could not find Captain Lambton of the Naval Brigade until Wednesday morning. I hoped that my experiences as gunnery officer in many land engagements in Africa would be of use. He welcomed me on as a member of his ship, H.M.S. Powerful. He had earlier lost his Commander who had volunteered for the Western front. I had the experience to help fill this role if need be. My expertise in gunnery was well received. We were able to jointly confirm that we were similarly decorated with the order of Medjidie. Lambton had also been present at the battle of Tel-el-Kebir in Egypt at the same time that l was landing troops and material at Suez. I was invited to join his company as Naval Lieutenant (Retired) from 1st day in November 1899. Another Lieutenant, Edward Stabb, from the Naval Reserve also joined as a volunteer that day. That same afternoon, the enemy cut the telegraph wire and blew up the railway line from Colenso. The siege of Ladysmith began in earnest.”[xxvi]

Given charge of a 12-pounder and Maxim gun, he quickly saw action:

“We were returning the fire of the "Long Tom" that the enemy had dragged up onto Pepworth Hill. The Boers made splendid shooting. Their shells burst all round our position. About 09:00 am a flash and a burst of white smoke was seen again. We had about twenty-five seconds to take cover, but this shell unfortunately fell inside our bastion. It was not built high enough. Poor Lieutenant Edgerton was hit by the ninety-six pound shell. Three of our bluejackets were wounded at the same time. Edgerton lost his right leg above the knee and his left below the knee. I was close to him at the time. Surgeon Fowler was on the spot and did all he could for him. The bluejackets lifted him tenderly onto a dhooly until he could be taken to hospital in an ambulance wagon. He was so plucky. He said that he was afraid that his cricket days would probably be over. He lit a cigarette as he was being carried down to the hospital. The doctor operated on him as soon as possible, but the shock was too great. Although he did regain consciousness after the operation, he died. Both legs had to be amputated. Everyone in the Naval Brigade was upset.”[xxvii]

“Twenty-five odd rounds were fired from each of our big guns on the first day. We had to ration this down as the siege wore on. The order was ‘Sharp’ then ‘Fire.’ A horny hand would come down on the lanyard; click went the striker; the gun recoiled back and then flew forward again with a deafening bang. The smell of cordite and acrid smoke would float out of the embrasure as the first lyddite shell hurtled towards the Boer gun. The breach was swung open again. The empty cordite cylinder was pulled out. A man, ready with another shell in his arms shoved it well home through the smoking breach. Another put in a fresh charge. With a clump the breach was closed, and the gun was ready for action once more. There was still time to watch the accuracy of the first shell before making any adjustment to the sightings for the next. Everyone craned forward eagerly at the target. It was a distant Long Tom. A great yellow cloud shot up. The shell had done its work.”[xxviii]

Mentioned in despatches by Captain Lambton, Tyndale-Biscoe returned home in the H.M.S. Powerful, arriving to a triumphant reception at Portsmouth in April 1900:

“I had to undergo the painful operation of public dinners that had been arranged. The one given by the Mayor and corporation at the Portsmouth Town Hall on 30 April turned out to be a riotous affair. The bluejackets at the long tables cheered each other to the rafters, whilst the distinguished hosts and officers tried to listen to the toastmaster above the din. The Naval Officers gave us an additional dinner at their club in Portsmouth. We had to attend yet another dinner in London, given by the Mayor in the inspection of the Naval Brigade by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle on 2 May.”[xxix]

Tyndale-Biscoe was mentioned in Despatches from Capt. Lambton to General Sir George White: “…Retired Lieutenant Edward C. Tyndale-Biscoe who handsomely volunteered his services on 1st November 1899, has been of greatest assistance to me. His experiences in the Sudan in 1884 and the Mashonaland and Matabele campaigns 1890 to 1897 rendered him a very valuable and reliable officer...”

In April 1902 Tyndale-Biscoe was specially promoted to Commander (Retired) for distinguished service during the siege of Ladysmith.

The final years

I am indebted to Marilyn Yurdan who sent me the following extract from his book 'Sailor Soldier'

On pages 275-6, Edward writes how he met his first wife, Ina Sandeman, at Harry Sandeman's wedding. "She was tall and elegant with long dark hair. Above all, she had a sense of humour."They were married on 1st December 1900 in London. She was the daughter of his uncle, John Sandeman. "Apart from Ina being beautiful, we developed a deep-seated friendship that transcended everything. Some say that we were also completely compatible. We shared the same value systems.It was an affinity. However, we did decide upon a supreme sacrifice. We chose not to have any children.'

He always refers to Ina with great affection and pride. Sadly, she died in February 1932 and Edward married again in the November of that year. Sybil Muriel Kathleen Ashworth was a much younger cousin, 20 years younger, in fact and seems to have made him happy. This time there is no record of any mention of the offspring factor!

The outbreak of World War I found Tyndale-Biscoe in Kashmir visiting his brother Cecil and recovering from a broken leg sustained in a vehicle accident. He went on to serve as a Major in the Censorship Office in Delhi, retiring in 1920.

He retired to the south coast in England living on Hayling Island near Portsmouth and died on 13 June 1941 aged 76.

Dix Noonan Webb description of the medals

Egypt and Sudan 1882-89, dated reverse, 2 clasps, Tamaai, Suakin 1884 (E. C. Biscoe, Midn., R.N., H.M.S. Euryalus); British South Africa Company Medal 1890-97, reverse undated, 4 clasps, Mashonaland 1890, Matabeleland 1893, Rhodesia 1896, Mashonaland 1897 (Lt. Tyndale-Biscoe, E. C. - Pioneers); Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, 1 clasp, Defence of Ladysmith (Lieut. E. C. Tyndale-Biscoe, R.N., H.M.S. Powerful), last two clasps on the second attached by wire rivets, generally good very fine or better. Estimate £12,000-15,000 but sold for £30,000 on 10 December 2014.

Hoisting the Flag on Pioneer’s Day

David Tyndale-Biscoe says on a number of occasions that Edward attended each tenth anniversary gathering at Salisbury up until 1940, for the fiftieth anniversary of his raising of the flag. This is quite possible, although the table from Mrs Honey’s article indicates he only actually raised the flag again on 12 September 1932.

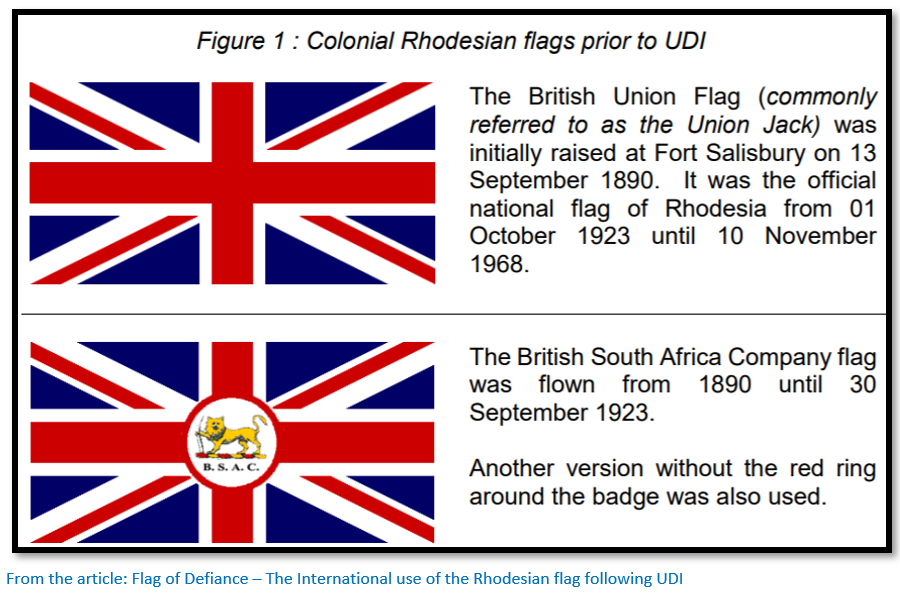

Richard Allport in Flags and Symbols of Rhodesia 1890 – 1980[xxx] states the following in relation to Pioneers Day which was celebrated from 1905 to 1979: “Although 12 September, anniversary of the arrival of the Pioneer Column at the site of Salisbury, had been commemorated a couple of times, it wasn't until 1905 that it became firmly fixed in the public mind as a special day for Rhodesia. In this year all Rhodesians had two days holiday on 5 July and 6 July, Rhodes's Day and Founders' Day, and the previous year, 1904, had seen the dedication of the Allan Wilson Memorial in the Matopos. These events led to a revival of public interest in the recent history of the country and a growing realisation that 12 September was a day of great national importance.

The new Mayor of Salisbury at that time, Edward Coxwell, decided that it was time that Salisbury's children became aware of the importance of their fathers' deeds and arranged a full programme of events to celebrate Occupation Day. In Cecil Square, near the original spot where the Union Flag had first been raised, a gum pole was erected in front of an audience of 250 children. A youngster named Frank Pascoe, as the first child to have been born in Salisbury, was given the honour of re- enacting the flag-raising ceremony. Colonel Raleigh Grey gave the children a talk on the subject and the children and their parents then proceeded to Hartmann Hill for a picnic and sports.

In the evening the adults held a dinner at the Commercial Hotel, the menu consisting of a chunk of bully beef and an army biscuit, to remind those present of the hardships the Pioneer Column had experienced.”

The information below is taken from Mrs Honey’s article in Rhodesiana Publication No 24 that states the idea of a ceremonial hoisting was that of Frank Buller, a jeweller, but otherwise the details are the same. The original flag had been sent to Cecil Rhodes and was kept in the Prime Minister’s house at Groote Schuur. So, the flag raised was the British Union flag; thereafter the British South Africa Company flag was flown until the end of the Chartered Company’s rule on 30 September 1923 when the British Union flag was used again.

The original flag was returned as a gift to the country by General Smuts in 1940 and used that year at the hoisting the flag ceremony; thereafter it has been stored in the National Archives. Only Pioneers or their descendants have had the honour of raising the flag on 12 September each year.

| Year | Flag-raiser | Reason |

| 1905 | Master Frank Salisbury PASCOE | first boy born |

| 1906 | Miss Freda VON HIRSCHBERG | first girl born here |

| 1907 | Master Leo MACLAURIN | son of 1890 Pioneer, A. MACLAURIN |

| 1908 | Miss Ida HONEY | daughter of Wm. Streak HONEY, 1896 |

| 1909 | No Flag-hoisting ceremony due to smallpox | |

| 1910 | Master Cecil CRAVEN | son of Mr. P. CRAVEN |

| 1911 | Master Laurie ARNOTT | son of Mr. S. ARNOTT |

| 1912 | Master Francis Huntington BROWN | son of Mr. Harvey 'Curio' BROWN |

| 1913 | Master David S. MILLS | son of Mr. J. W. T. MILLS |

| 1914 | Master Jim KENNEDY | son of Mr. J. H. KENNEDY |

| 1915 | Miss ARNOTT | daughter of Mr. S. ARNOTT |

| 1916 | Master ARNOTT | son of Mr. S. ARNOTT |

| 1917 | Master George SCHLACTER | son of Mr. John SCHLACTER |

| 1918 | Miss Molly SANDERSON | daughter of Mr. SANDERSON, Commercial Hotel |

| 1919 | Master Harold HARPER | son of Mr. Harry HARPER |

| 1920 | Master CRAVEN | son of Mr. P. CRAVEN |

| 1921 | Miss Lorna EDMONDS | daughter of Mr. J. Arnold Edmonds |

| 1922 | Miss Sybil CRAVEN | daughter of Mr. P. CRAVEN |

| 1923 | Miss Anna SCHLACTER | daughter of Mr. John SCHLACTER |

| 1924 | Master Laurence ARNOTT | son of Mr. S. ARNOTT |

| 1925 | Miss Rose SCHLACTER | daughter of Mr. John SCHLACTER |

| 1926 | Master Peter WHITELEY | grandson of Colonel Frank JOHNSON |

| 1927 | Master J. H. C. NICHOLLS | baby son of Major J. E. NICHOLLS |

| 1928 | Miss Gladys DREW | daughter of Mr. A. DREW |

| 1929 | Miss Barbara WINDELL | daughter of Mr. H. J. WINDELL |

| 1930 | Master J. H. C. NICHOLLS | son of Major J. E. NICHOLLS |

| 1931 | Miss Grace BERTRAM | daughter of Mr. C. P. BERTRAM |

| 1932 | COMMANDER TYNDALE-BISCOE, R.N. | hoisted the Flag in 1890 |

| 1933 | Master Walter EDMONDS | son of Mr. J. Arnold EDMONDS |

| 1934 | CAPTAIN HOSTE and Master Denton | 1890 Pioneer and one of his MATHEWS descendants |

| 1935 | Master Roy PILCHER | grandson of Mr. T. W. RUDLAND, O.B.E. |

| 1936 | Master Raymond George PEAKE | grandson of Mr. CARRUTHERS |

| 1937 | Master Estcourt Cresswell PALMER | grandson of Mr. J. A. PALMER |

| 1938 | Master Marcus EDMONDS | grandson of Mr. J. Arnold EDMONDS |

| 1939 | Master Gladwin CARRUTHERS | grandson of Mr. CARRUTHERS |

| 1940 | The Hon. Lionel CRIPPS | 1890 Pioneer. Speaker of the Legislative Assembly |

| The original flag used in 1890 and returned from Cape Town by General Smuts was hoisted. Not used again | ||

| 1941 | Master John Stace CARRUTHERS | grandson of Mr. E. CARRUTHERS-SMITH |

| 1942 | Miss June MARSHALL | granddaughter of Mr. T. W. RUDLAND, O.B.E. |

| 1943 | Miss Pamela BERTRAM | granddaughter of Mr. C. F. BERTRAM |

| 1944 | Master Roy H. CRIPPS | small grandson of Lionel CRIPPS |

| 1945 | Master Michael WHILEY | grandson of Mr. M. W. BARNARD |

| 1946 | Miss Jennifer RUDLAND | granddaughter of Mr. T. W. RUDLAND, O.B.E. |

| 1947 | Mr. J. A. PALMER | 1890 PIONEER, B.S.A.C Police |

| 1948 | Mr. J. L. CRAWFORD | 1890 PIONEER |

| 1949 | COLONEL DIVINE, D.S.O. | 1890 PIONEER |

| 1950 | Mr. T. W. RUDLAND, O.B.E. | 1890 PIONEER—President of the Pioneers and Early Settlers Society |

| 1951 | Master Lindsay CRAWFORD | grandson of Mr. J. L. CRAWFORD |

| 1952 | Mr. J. T. HARVEY | B TROOP PIONEER CORPS 1890 |

| 1953 | Mr. C. F. CREIGHTON | A TROOP B.S.A. POLICE 1890 |

| 1954 | Mr. R. CARRUTHERS-SMITH | B TROOP B.S.A. POLICE 1890 |

| 1955 | Mr. R. CARRUTHERS-SMITH | B TROOP B.S.A. POLICE 1890 |

| 1956 | Mr. F. EVERITT | PIONEER COLUMN 1890 |

| 1957 | Mr. F. EVERITT | PIONEER COLUMN 1890 |

| 1958 | Mr. E. R. B. PALMER | son of Mr. J. W. PALMER |

| 1959 | Mr. Clifford BOARDMAN | grandson of Mr. C. H. C. BOARDMAN |

| 1960 | Mr. G. BROOM | grandson of Mr. J. T. HARVEY |

| 1961 | Mr. R. A. FRY | grandson of Mr. Ellerton FRY |

| 1962 | Mr. F. B. JOHNSON | son of Sir Frank JOHNSON |

| 1963 | Mr. E. B. MACLAURIN | grandson of Mr. A. MACLAURIN |

| 1964 | Mr. N. A. TATHAM | grandson of Mr. A. TULLOCH |

| 1965 | Mr. C. DA VIES | grandson of Skipper HOSTE |

| 1966 | Mr. R. H. BRAY | son of Mr. Reginald BRAY |

| 1967 | Mr. G. ARNOTT | grandson of Mr. S. N. ARNOTT |

| 1968 | Mr. Lance DAVIS | great-grandson of Hon. Lionel CRIPPS |

| 1969 | Mr. Neville BERTRAM, C.M.G., O.B.E. | son of Mr. C. P. BERTRAM |

| 1970 | Mr. George SCHLACTER | son of Mr. John SCHLACTER |

| 1971 | Mr. F. I. H. NESBITT | great-grandson of Mr F. Nesbitt |

| 1972 | Mr. Geoffrey Nicholas BRAKSPEAR | great-grandson of Mr Harry SANDERSON |

| 1973 | Mr. John ORPEN | grandson of Mr Arthur Francis ORPEN |

| 1974 | Mr. Robert Reginald BRAY | great-grandson of Mr Reginald BRAY |

| 1975 | Trooper Barry Desmond BAWDEN | great-grandson of Mr Harry Slogget BAWDEN |

| 1976 | Miss Margaret Ruth GIBSON | great-granddaughter of Colonel C. H. DEVINE, D.S.O. |

| 1977 | Master Grahame David JELLY | great-grandson of Mr Sydney Nathaniel ARNOTT |

| 1978 | Patrol Officer Colin MACLAURIN B.S.A.P. | great-grandson of Trooper A. J. MACLAURIN |

Annual Field Gun Competition

The Royal Navy's field gun competition is a contest between teams from various Royal Navy commands, in which teams of sailors compete to transport a field gun and its equipment over and through a series of obstacles in the shortest time.

Its origins come from the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and specifically from the Royal Navy landing guns from HMS Terrible and HMS Powerful to help in the 119-day siege of Ladysmith in which Edward Tyndale-Biscoe took an active part. The defenders were helped enormously by the arrival of Captain the Hon. Hedworth Lambton of the Naval Brigade with 280 bluejackets, four 12 pounders and two 4.7 inch field guns.

The six field guns each weighed nearly half a metric tonne and had to be manhandled over extremely rough terrain. Their achievement in teamwork, leadership, and moral and physical courage has been commemorated since 1907 in the form of annual Field Gun competitions for the Brickwood’s trophy, an exact silver reproduction of a 12 pounder field gun and its sailor crew of seven.

The Competition Today

With the ending of the Royal Tournament in 1999 the decision was to hold the Competition annually at HMS Collingwood in Fareham, Hampshire, celebrating its centenary last year. Currently about 21 crews compete, representing units of the Royal Navy and Royal Marines as well as the British Army and Royal Air Force, and as such is well supported by senior ranks of all three Services. Each crew of eighteen races to assemble an antique field gun and run with it, disassembling, and reassembling as the competition requires, before dramatically dragging the gun home, maintaining the spirit of the Royal Navy’s contribution to the relief of Ladysmith.

References

D. Tyndale-Biscoe. Sailor Soldier. Private Publication by D. Tyndale-Biscoe, Simonstown 2001

H. Tyndale-Biscoe. The Missionary and the Maharajas; Cecil Tyndale-Biscoe and the Making of Modern Kashmir. Bloomsbury 2019

J.B.L. Honey. Hoisting the Flag on Pioneers’ Day. Rhodesiana Publication No 24, July 1971

H.F. ‘Skipper’ Hoste. (Edited by N.S. Davies) Gold Fever. Pioneer Head, Salisbury 1977

B. Berry. Flag of Defiance – The International use of the Rhodesian flag following UDI. https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/71112/Berry_Flag_2019.pdf?sequence=1

W. Ellerton Fry. Occupation of Mashonaland. Books of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo 1982

D. Gray. Advising of Mrs J.B.L. Honey's correspondence in Rhodesiana Publication No 40, 1979 with the names of the 1971 to 1978 flag raisers

[i] A zariba is a thorn fence

[ii] Sailor Soldier, P27

[iii] Ibid, P28

[iv] Wikipedia: Battle of Tamai

[v] Sailor Soldier, P30

[vi] Ibid, P32

[vii] Suakin to Berber on the Nile river was just 84 kms (52 miles) and Khartoum was just another 322 kms (200 miles) along the banks of the Nile to relieve General Gordon. In contrast General Sir Garnet Wolseley favoured the all-river route over numerous cataracts totalling 2,655 kms (1,650 miles) and the 9 month delay brought about by building 800 flat-bottomed whale boats meant General Charles Gordon’s forces were overwhelmed and Gordon killed within two days of Wolseley’s forces arriving at Khartoum.

[viii] Sailor Soldier, P40

[ix] Ibid, P44

[x] Ibid, P77

[xi] Ibid, P80

[xii] Gold Fever, P41

[xiii] Sailor Soldier, P93

[xiv] Ibid, P106-7

[xv] Ibid, P109

[xvi] Ibid, P110

[xvii] Ibid, P114

[xviii] Ibid, P129

[xix] By ‘red day’ i.e., dawn

[xx] Sailor Soldier, P157

[xxi] Ibid, P159

[xxii] Ibid, P161

[xxiii] Ibid, P184

[xxiv] Ibid, P185

[xxv] Ibid, P192

[xxvi] Ibid, P229

[xxvii] Ibid, P231

[xxviii] Ibid, P232

[xxix] Ibid, P270

[xxx] Flags and Symbols of Rhodesia 1890-1980 by Richard Alport on the website Rhodesia.nl