Africa’s National Parks in the midst of a pandemic-induced conservation crisis

An improving wildlife situation prior to COVID-19

In the last few years there have been lots of encouraging signs from Africa’s National Parks. Levels of poaching have decreased, attempts are being made to discourage habitat fragmentation and wildlife regions are being encouraged to interconnect; tourism and interest in wildlife were on the up. The increased tourist traffic was making local communities see that wildlife is an asset that needs to be protected and lessened the urge to poach for bushmeat. Aid money from charities and governments to assist National Parks with salaries and resources had been increasing.

Kim Young-Overton director of Panthera’s Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, which includes Kafue National Park in Zambia says: “After 18 months of intense patrolling, we felt like we were just turning a corner in terms of getting on top of poaching and wildlife beginning to recover.”[i] She says that since the pandemic began, bushmeat poaching has returned to the same level as two years ago before they instituted improved security. The number of snares found rocketed from 25 in May – August 2019 to 136 in the same period in 2020 and bushmeat seizures have substantially increased.

Wildlife conservation in Africa has been fragile

Most of the state sponsored wildlife agencies such as Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) have received very limited funding or “shoestring budgets” from the Zimbabwe government which has resulted in an over-reliance on tourism to fill the gap. COVID-19 has shown how fragile this model is. Once the pandemic is over, community development needs to be at the forefront of aid packages.

Wildlife populations will take far longer to recover than they do to decline and the poverty in surrounding local communities will take time to reverse its trend.[ii] Conservationists have been warning for years about the fragility of the model which is almost wholly reliant on tourism and the whims of donors.

Suddenly everything stops

Virtually overnight, it was “like a tap [was] turned off,” Young-Overton says. The tourists disappeared, taking with them the dollars that the National Park and surrounding communities depend on. The absence of foreign visitors also left a dent in security and without all those extra eyes and ears on the ground, it was “like leaving the front door open.” Poachers could now enter the park without worrying about running into safari operators and their guests.[iii]

The lasting impact of COVID-19 on African wildlife parks is not yet evaluated but the local poverty brought about will be long-lasting

A recent IUCN special issue of PARKS, the journal of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas concluded that conservation efforts in Africa and Asia were most severely affected by the pandemic.[iv] More than half of protected areas in Africa reported that they were forced to halt or reduce field patrols and anti-poaching operations as well as conservation education and outreach.

African Park Managers from Uganda, Kenya and Gabon briefed Members of the U.S. Congress on 12 May 2020. It was early days in the pandemic, but it was already disrupting the delicate balancing act for wildlife.

Their message was that new policies were needed to maintain the thousands of jobs in communities that are sustained by wildlife conservation and have been disrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They feared that if this is not done thirty years of solid conservation progress could be reversed.[v]

At the time the full extent of travel bans, border closures and holiday cancellations on protected wildlife areas, safari operators and local communities was not known but was quickly being felt as the income streams that previously supported jobs and economies came to an abrupt end.

Edwin Tambara cited Namibia where 86 conservancies will lose nearly $11 million in income that will affect the livelihoods of 700 community game guards, 300 support staff and 1,175 locally-hired others…many would lose their jobs. In Kenya wildlife conservancies are preparing to lose $120 million in income that will have a much bigger impact.[vi]

Many National parks receive only nominal sums from their governments

The IUCN report revealed that a survey of game rangers in more than 60 countries found that more than one in four rangers had seen their salary reduced or delayed, while 20% reported that they had lost their jobs due to COVID-19 related budget cuts. Rangers from Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Africa and Asia were more strongly affected than their peers in Europe, North America and Oceania.

Nuwer and Chadwick write that in the U.S. the taxpayers subsidize their conservation areas, but this is often not the case in Africa and some National Parks even pay the government a portion of their income.[vii] For most National Parks and conservation areas the amounts collected from tourism and other sources are not sustainable and “they lack the resources to actually implement conservation on the ground.” They quote from a 2018 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper that found “that 90% of the nearly 300 protected savannah ecosystems in Africa face crippling funding deficits—to the collective tune of at least a billion dollars.”

“Budget deficits come at a time when Africa’s human population is growing, and the continent is developing quickly,” says Peter Lindsey, director of the lion recovery fund at the Wildlife Conservation Network, and lead author of the findings. “This poses a risk that underfunded protected areas will become swamped by human pressures.”

Tourism is still vital to the lifeblood of National Parks

It is estimated that tourism to Africa brings in revenue of $29 billion annually and the conservation sector employs around 3.6 million people.[viii]

While Ebola, terrorist attacks, and political unrest have driven visitors away from various countries and regions in the past, “nothing has ever hit all at once before. That’s a shock I don’t think anyone saw coming” says Tim Tear, the tropical program director at the Biodiversity Research Institute.[ix]

Researchers writing in Nature Ecology and Evolution say 90% of African tour operators have experienced a 75 - 90% decline in bookings. For some, it has dropped by 100%. In Mozambique, for example, more than half of the country’s protected land is allocated for management and use by trophy hunting companies, all of which have lost most or all of their bookings to the pandemic. “Zero foreign clients is where we’re sitting at the moment,” says Holly Rosier, the head biologist at Coutada 9, a 4,300-square-kilometer (1,660-square-mile) conservation area that relies on hunting proceeds for virtually 100% of its budget. “It’s a complete nightmare.”

With zero income one-third of the game scouts have been laid off. Local communities normally receive 25% of the profits, but none will be forthcoming this year. Rosier says: “It’s going to be really important to make clear why they’re not getting that money, because any form of resentment will come back ten-fold.” Poaching will probably also increase.

Informal employment will be severely impacted

Just as in European cities the lockdown measures have seen people in Africa moving from the cities to their communal areas. An estimated 350 million Africans are in informal employment and their move from the cities into rural areas which already experience high unemployment and poverty will only increase the chances that they will be forced to resort to illegal activities such as poaching and wildlife trafficking.[x]

Poaching has returned

If proactive steps are not taken poaching will accelerate, as will other illegal activities like mining, logging and livestock grazing.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) sent out a survey to wildlife managers across Africa and received responses from nineteen countries. Half said that the pandemic had crippled their ability to conduct anti-poaching activities. All reported at least some impact to their conservation operations, including a compromised ability to pay staff salaries, to monitor illegal wildlife trade, and to reduce human-wildlife conflict in local communities.[xi]

Since the pandemic began poaching for bushmeat has returned to levels last seen several years ago as livelihoods have been upended and poverty increasing. In Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park, for example, rangers have grown used to battling sophisticated poaching gangs that target rhinos. But since Covid-19 hit, they have started intercepting: “groups with rifles coming in with donkeys, to shoot antelope, buffalo, and kudu and take the meat back,” says João Almeida, a wildlife veterinary officer at Saving the Survivors in Mozambique. “This is something they’ve never had before on that scale.”[xii]

Food security is threatened

Country-wide lockdowns have disrupted the internal supply chains of many African economies as road transport has ground to a halt. East Africa and the horn of Africa have suffered from swarms of desert locusts which have destroyed crops and Southern Africa is still struggling with the effects of years of drought and floods.

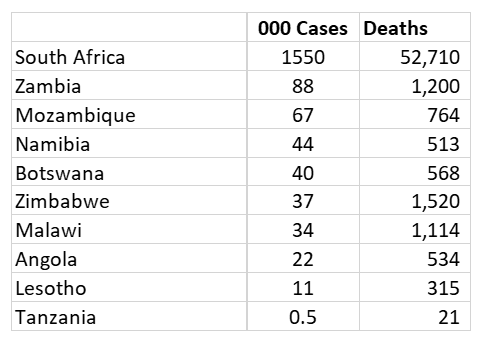

Southern Africa Official COVID-19 cases to end March 2020

The comparatively small number of COVID-19 compared with Europe and the America’s is probably a big understatement. Many countries were not in a position to undertake testing and the smaller number is no reason to discount the enormous impact the pandemic has had on their economies with lockdowns and a complete stop to tourism.

Carlos Manuel Rodríguez, CEO and Chairperson of the Global Environment Facility wrote in the IUCN report: “Investing in nature conservation and restoration to prevent the future emergence of zoonotic pathogens such as coronaviruses costs a small fraction of the trillions of dollars governments have been forced to spend to combat COVID-19 and stimulate an economic recovery. To do so will also safeguard jobs, human health, incomes and essential natural resources for billions of people. We cannot say we are building back better unless we do so whilst also protecting the natural world.”[xiii]

Assistance needs to be targeted

Edwin Tamara[xiv] argues that aid packages need to be targeted to support those rural “communities on the frontline of wildlife conservation.” If sufficient jobs are not created to those communities most in need, there is a risk that 30 years of gains in changing behaviours in Africa will be lost. He believes the model of helping communities’ benefit from wildlife conservation results in incentivization of conservation efforts and combats threats to wildlife.

Nuwer and Chadwick argue there are already conservation models across Africa that are self-sustaining, resilient and equitable. Conservationists they say argue: “If it pays, it stays” is a phrase commonly heard in Southern African countries with regard to justifying wildlife’s presence on the landscape. But this sentiment could just as well be applied across the continent. Conservation for conservation’s sake is not a luxury that Africa’s growing, oftentimes impoverished populations can afford.

Wildlife conservation is often not a priority

Some countries such as Kenya have introduced emergency subsidies to support game rangers and other short-term conservation needs, but in most African countries, conservation ranks far down the priority list in terms of pandemic relief.

This is not unusual as even in ordinary times: “National Parks have always been neglected when allocating national budgets,” says John Waithaka, the East and Southern Africa regional vice chair of the IUCN’s World Commission on Protected Areas.

It remains to be seen to what extent the international community will step up in the longer term to support conservation efforts devastated by the pandemic. Clearly a lot depends on how quickly donor economies recover.

Zimbabwe

Patience Gandiwa, an executive technical advisor on international conservation affairs for Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority says ZimParks: “does not get a single penny from the [Zimbabwe] treasury” and all its revenue comes through tourism, donations, land leases and grants.[xv]

Patience and her colleagues were looking forward to hiring hundreds of new rangers, investing in amenities for the agency’s 3,200 existing staff, and renovating tourist camps across the country. “2020 was promising to be such a big year,” she says. “Then Covid visited us.” ZimParks has enough funds to pay staff salaries, at max, through the first quarter of 2021—and not at a level that keeps pace with Zimbabwe’s high inflation rates. “You get enough to survive,” Gandiwa says. “We’re just hoping with the slow opening up of tourism we’ll start to have a little bit more income, so we don’t completely run dry.”

Wildlife Conservation success stories

The good news is that a number of African leaders are already well aware of the importance of conservation to their economies. Benjamin Mkapa, the late former President of Tanzania, spoke by video conference to dozens of heads of Africa’s protected areas. National Parks, he emphasized, are key to creating “the healthy, prosperous, and sustainable Africa that Africans so desire,” and conservation should be made the centrepiece of new sustainable and resilient economies.

In Cameroon, for example, land and wildlife belong solely to the government—a top-down approach that “is not always that good,” says Roger Fotso, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Cameroon program. Corruption, mismanagement and a lack of resources have prevented the country from realizing its full potential for conservation and have also excluded Cameroonians from a sense of environmental ownership. “People do not see the direct benefit,” Fotso says.[xvi]

However, progress has been made. In 2012, for example, the Wildlife Conservation Society worked with the Cameroon government and rural communities to create Deng Deng National Park, a forested landscape home to gorillas and chimpanzees. The original plan was to secure 155 sq. kms (60 sq. miles), but there was such an outpouring of community support that the area was expanded to 673 sq. kms (260 sq. miles). The communities living nearby: “were part of the discussion, they did not just sit back and see something coming,” Fotso says. “There’s many examples like that, showing that people will be willing and supportive if they feel like they’re a part of the process.”

Namibia an outstanding example

Namibia has established 86 communal conservancies which manage 171,000 sq. kms (66,000 sq. miles) of wilderness since 1998. The elephant population has more than tripled, it has become a stronghold for critically endangered black rhinos and at least 150 desert lions— formerly estimated to number fewer than 25—now roam the country’s northwest. This has brought benefits through jobs, development and opportunities, both people and wildlife can flourish.

But even Namibia’s conservancies are still vulnerable as 90% of their income comes from photographic and hunting tourism and this has dried up emphasizing the importance of developing other, more sustainable, diversified and resilient ways to earn revenue from nature.

Public-Private partnerships may be part of the solution

In the near term, public-private partnerships are one tool that African governments can turn to help build their conservation capacity. For example, African Parks, a South Africa-based non-profit group, has taken over managerial duties for 16 formerly struggling National Parks in 11 countries, including in tourist-scarce places such as Benin, Chad, and DRC and Zimbabwe. Funding from philanthropists, non-profit groups and the E.U. and U.S. allows African Parks to bridge the budgetary gap while it rehabilitates the environment, wins over local communities and builds up tourist infrastructure.

African Parks, in partnership with the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (Zimparks) signed a 20-year agreement to manage Matusadona National Park on 1 November 2019. At 1,470 sq. kms, this stunning and unique landscape presents enormous potential for both wildlife and tourism.

Planning for the future

Adrian Phillips, Co-Editor of the IUCN’s special edition of PARKS wrote: “During the coming year, governments and others will be gathering in a series of international meetings to decide how to stabilise our climate, save biodiversity, secure human health and revive the global economy. Through all these events should run this golden thread: learn the lessons of COVID-19 by protecting nature and restoring damaged ecosystems. This is the mission that all with the power to bring about change must now pursue.”[xvii]

Gary Tabor, President of the Centre for Large Landscape Conservation and Chair of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas’ Connectivity Conservation Specialist Group added: “Now more than ever, we understand how human, animal, and ecosystem health are inextricably linked. As the world seeks relief from the current COVID-19 pandemic and now develops strategies to prevent future pandemics, national parks and protected areas have an essential, protective public-health role to play. Intact nature buffers the risk of pandemic spill over from wildlife to people. It is a value that can be easily incorporated into existing protected-area management strategies, but this has yet to be done.”

References

Rachel Nuwer and Peter Chadwick (Photos) 9 January 2021, Quartz Africa: Photos: Africa’s nature parks are in the midst of a pandemic-induced conservation crisis

E. Tambara. 21 March 2021. African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) Coronavirus in Africa could reverse 30 years of Wildlife conservation gains, harming interconnected communities and livelihoods

12 March 2021. COVID-19 fallout undermining nature conservation efforts – IUCN publication

Notes

[i] Photos: Africa’s nature parks are in the midst of a pandemic-induced conservation crisis

[ii] Africa’s-safari-parks-face-covid-induced-conservation-crisis/

[iii] Ibid

[iv] COVID-19 fallout undermining nature conservation efforts – IUCN publication

[v] Coronavirus in Africa could reverse 30 years of wildlife conservation gains, harming interconnected communities and livelihoods

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Africa’s-safari-parks-face-covid-induced-conservation-crisis/

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Ibid

[x] Coronavirus in Africa could reverse 30 years of wildlife conservation gains, harming interconnected communities and livelihoods

[xi] Africa’s-safari-parks-face-covid-induced-conservation-crisis/

[xii] Ibid

[xiii] COVID-19 fallout undermining nature conservation efforts – IUCN publication

[xiv] Coronavirus in Africa could reverse 30 years of wildlife conservation gains, harming interconnected communities and livelihoods

[xv] Africa’s-safari-parks-face-covid-induced-conservation-crisis/

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] COVID-19 fallout undermining nature conservation efforts – IUCN publication