Figtree, or Fort Molyneaux and the 1896 Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela

GPS 20°22'27.70"S 28°19'22.24"E Altitude 1,382 metres (4,560 ft), Rainfall 521 mm (21 in)

Introduction

This article is from a number of sources. Robert Cherer Smith’s excellent book Avondale to Zimbabwe, Rhodesiana articles from the website of The History Society of Zimbabwe and bits from the Rhodesiana.com website.

Figtree, like Marula, (see the article A look at present-day Marula, between Bulawayo and Plumtree under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com, owes its existence to the railway line. Early locomotives were steam powered and coal burning and ran on the standard 3ft 6in (1067mm) gauge in use throughout southern Africa. Ultimately, running out of water was always a serious risk, so railroad operations were meticulously planned around water availability to keep the trains running safely and on schedule. Uphill gradients and heavy loads consumed water much faster than running on flat track and although the altitude difference between Plumtree (1,374 metres – 4,508ft) and Bulawayo (1,358 metres – 4,455ft) was small, this takes no account of the gradient rises and falls along the track.

Railroads at the time typically had water stops (towers and tanks) every 10 to 20 miles (16 – 32 kms) to ensure that trains always had the opportunity to replenish their water supply that was vital for their boilers. The Plumtree to Bulawayo line was no exception and the water stops were evenly spread out. Plumtree to Marula was 31 km, Marula to Figtree was 32 km and Figtree to Bulawayo was 36 km.

For more information on the railway line to Bulawayo see the article A look at present-day Marula, between Bulawayo and Plumtree under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Fort Molyneux

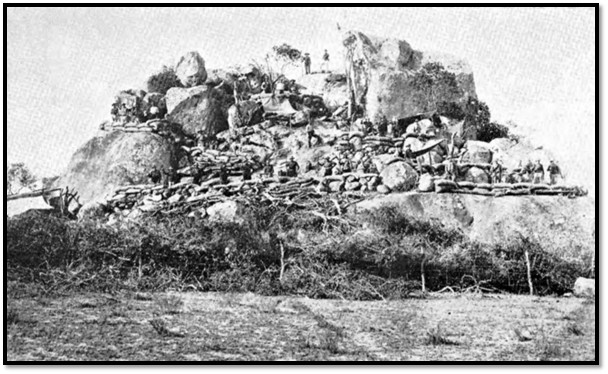

NAZ: Fort Molyneux, Figtree

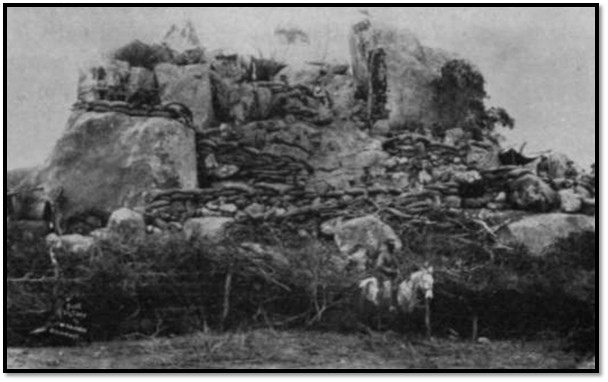

NAZ: Fort Molyneux, Figtree viewed from the west

I.J. Cross in his Rhodesiana Publication article states that the steps cut into the rock half-way up the kopje can still be seen. He writes that the fort is marked on the Rhodesia Surveyor General 1:50,000 map reference 2028A at grid reference 337395. He describes the fort as being built on “a small isolated kopje in open ground on the south edge of the old Bulawayo-Mangwe road. The Gulula river skirts the south-eastern foot of the kopje. The fort is a fortified kopje. There are no walls, but a few rocks have been placed along the top of the large boulder at the south-western foot of the kopje. Some steps have been cut into the rock just above this point. An enclosed area at the north-eastern foot of the kopje has been cleared of rock. This was originally cleared to make a stable for the horses.

Other remains. The bases of three huts can be seen around the western and northern foot of the kopje but since the site was used by the BSA Police as a post well into this century these may well be post-1896 structures. Traces of the old telegraph hut and store which date from the Rebellion, can be seen about 200 yards west of the Fort just north of the road.”[1]

Figtree’s role in the 1896 Matabele rebellion or Umvukela

At the start of the rebellion in late March 1896 the road south to Fort Tuli and on the eastern edge of the Matobo Hills became impassible to travellers and the Zeederberg coach due to amaNdebele attacks. The only safe route available for a relief column and supplies was the road leading west from Bulawayo to the Mangwe Pass, the original Hunter’s Road into the country. See the article The Hunter’s Road - followed on maps under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Frederick Courtenay Selous, now promoted to captain, was put in charge of this road and the telegraph line to Kimberley. Within a month Selous had selected the following sites for forts to be established every 8 – 10 miles (13 – 17 kms)[2]

1896 Forts guarding the Bulawayo - Mangwe road | |

Location | Fort name |

Wilson’s Farm 7 miles (11 kms) from Bulawayo | Dawson |

Khami river | Khami |

Mabukutwane | Marquand |

Figtree | Molyneux |

Shashani Pass | Halsted |

Matoli 15 miles (24 kms) from Mangwe | Luck |

Mangwe | Mangwe |

Each fort had a garrison of 30-50 men and was often named after its builder or first commander. Thus Mabukutwane was named after Lieut F.J. Marquand, a Bulawayo architect who helped choose the site and supervised construction although Selous was its first commander.

Mangwe was at the foot of the Mangwe Pass and was named after John Lee whose farm and house was 1.5 miles (2.4 kms) away on the Hunter’s road and in the 1860’s – 1890 was the main entry point for all the traders and hunters who wanted to enter the amaNdebele kingdom.[3]

The fort had originally been built by the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) in 1893. It was of circular construction, about 80 feet (24 metres) in diameter and was dug below ground level with stone supporting walls and roofed over with mopane poles and thatched but was abandoned by the BBP in 1894.

At the outbreak of the amaNdebele rebellion about 150 men, women and children formed a laager here with their ox-wagons forming two circles around the periphery of the fort. Unfortunately, the fort had been used to store maize after the BBP left and was full of rodents. The fort’s commander, Major Armstrong, failed to maintain any real discipline. There was friction between the Afrikaner and British settlers, the tensions, anxiety and discomforts within the fort made living demanding and the situation deteriorated so that Hans Lee, son of John Lee and the hunter Cornelius van Rooyen were forced to step in and impose the discipline necessary for good order.

Selous led a patrol to investigate rumours, ‘that in the Mangwe laager order and discipline were conspicuous by their absence.’ He returned however, with praise for Armstrong and van Rooyen, having found the laager, “in excellent order.” However, in May 1896 Colonel Plumer leading the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) through the Mangwe Pass on their march to Bulawayo commented, “Any value this fort might have had as a defensive work were quite nullified by the collection of huts, waggons and paraphernalia of all kinds huddled inside.” During the rebellion, six children were born at the laager at Mangwe.

With peace after 1897 the garrison at Mangwe reduced to about six troopers and even they were not often present. A quote from the Bulawayo Chronicle, dated 31 May 1897 reads as follows: “Arrived Mangwe. Fort deserted. Police removed thirty miles west, near railway. One telegraphist and one storekeeper here.”[4]

Colonel Plumer took command of the line of forts from 16 May 1896 from his base at Fort Khami. The existing system whereby all transport was escorted between forts was replaced with a single dawn patrol from each fort. However, a shortage of horses made the task difficult and many of the Bulawayo volunteer force did not take kindly to the military discipline. There were also disputes over pay and many volunteers felt that having successfully carried out the initial fighting and defence they should be allowed to take part in the active operations to come. Although many requested to resign these were mostly refused.

Unrest at Fort Molyneux (Figtree)

At Fort Molyneux 90 sick horses left there by Plumer were driven off by the amaNdebele half an hour after he left and could not be recovered. In June orders were sent to the Sergeant-Major in command, “Please report as soon as you have put your fort in such condition as to render it safe from catching fire.” As this order was not carried out, the entire garrison were replaced. Two weeks later came a report from Fort Molyneux that a rebel force was outside the fort. Captain Tyrie-Laing[5] and 200 men mostly from the Belingwe Field Force (BFF) were sent, but the reports were false. They found Lieut Botha, the officer commanding, was drunk and the corporal under arrest for shooting the sergeant. Botha was relieved of his command, but before returning under arrest to Bulawayo he managed to make matters even worse by cutting the telegraph wire. Tyrie-Laing remained at Figtree and use it as a base for his skirmish into the Matobo and the nearly disastrous events at Inugu on 20 July 1896. See the article David Tyrie Laing and the near-disaster Matobo Hills engagement in the 1896 Matabele Uprising or Umvukela under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Matobo hostilities cease: General F. Carrington orders a withdrawal from static positions

The first of the Indabas that Cecil Rhodes held with the amaNdebele Chiefs took place on 20 August 1896 with the second Indaba just seven days later. See the article The Matabele uprising or First Umvukela Indaba Site (Rhodes Indaba site) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

With the ending of the fighting in the Matobo, Carrington the commander of the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF} decided to reduce the number of troops in static positions and transfer them to Mashonaland where the Mashona Rebellion had broken out in mid-June 1896.

In September Forts Bembesi, Dawson, Halsted, Hope Fountain, Spargo’s and Umzingwane were abandoned and the garrisons at Khami, Molyneux (Figtree) Luck and Mangwe were each reduced to 20 men. By mid-October Forts Khami, Luck and Marquand had also been abandoned and the total garrison force reduced from 347 MRF to 100 British South Africa Company Police.[6] The settler effort would be a switch from hostile operations to peaceful engagement in an attempt to persuade the amaNdebele to surrender under the District Commissioners and Police.

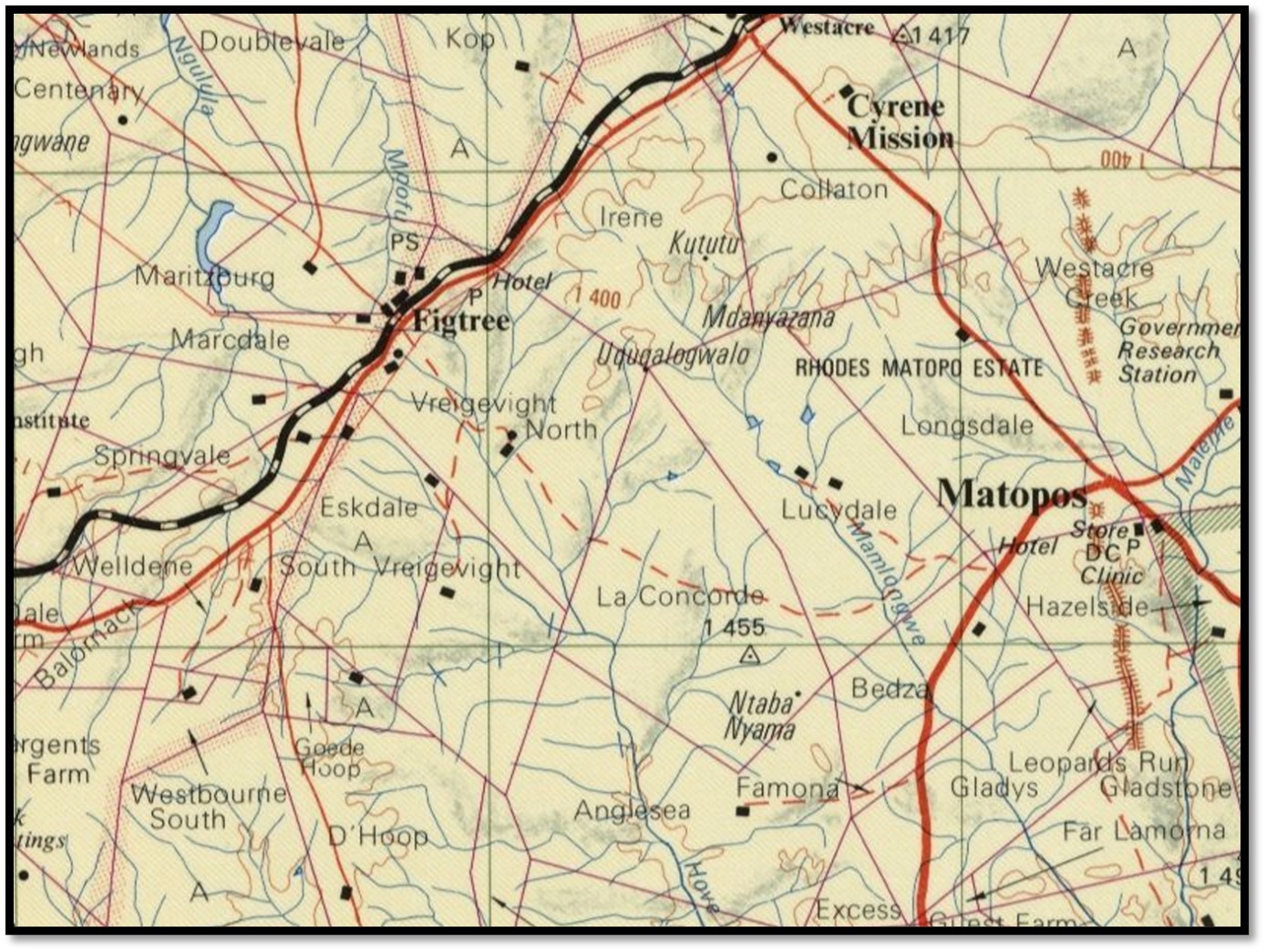

Figtree and surrounding farms from the 1:250,000 map sheet SF-35-3 Plumtree published by the Surveyor-General, Rhodesia 1975

The Railway from Plumtree to Bulawayo

The historic photos from the steam age and descriptions below are from Nigel Tout’s interesting website http://www.nigeltout.com/html/zimbabwe--towards-plumtree.html

http://www.nigeltout.com/html/zimbabwe--towards-plumtree.html

National Railways of Zimbabwe 'Garratt' steam locomotive 20th class 4-8-2+2-8-4 no. 730 'Insuga' (built by Beyer Peacock in 1954) performs a run-past heading west from Bulawayo towards Plumtree with the 'Union Limited Zambezi' train, Zimbabwe, 1st August 1992. It is about to pass class 15A 'Garratt' 4-6-4+4-6-4 no. 414 'Bhejane' ('Black Rhino, built by Société Franco-Belge in 1952) which is waiting in a passing loop on a freight train from Botswana.

http://www.nigeltout.com/html/zimbabwe--towards-plumtree.html

Rhodesian Railways 12th class 4-8-2 steam locomotive no. 190 (built by North British Locomotive Co. in 1926) and 16A class 2-8-2+2-8-2 'Garratt' no. 612 (built by Beyer Peacock in 1938) perform a run-past in the late afternoon with the 'Union Limited Zimbabwe' train between Plumtree and Bulawayo, Zimbabwe on 1 August 1992

Figtree information from Avondale to Zimbabwe

Figtree station

The village was named after a wild fig tree (Fiscus scraba) which was a well-known landmark. According to Cherer Smith it was also the place where, before the occupation, missionaries, hunters, traders and others had to await the permission of the King (Mzilikazi then Lobengula) to enter his domain.[7]

When the telegraph line from the south was being constructed, arrangements were made by Captain Norris Newman, who was Reuter's correspondent in Bulawayo, to send his telegrams to the telegraph head. He also accepted private telegrams, which were charged according to the distance the telegram had to be taken to the telegraph head. Newman made special stamps with three values of $1, 50c and 25c. A reduced charge operated from the Figtree railway camp, but when the railway line reached Figtree the British South Africa Company introduced a similar service at a charge of 10c, and Newman discontinued his scheme.

The area was first surveyed by Maxwell Edwards, but he had to return to Bulawayo when the rebellion broke out in 1896. On his way to safety, he was attacked by a detachment of Matabele, but he managed to evade being captured and put to certain death.

At first Figtree consisted of a store, post office and police station with only six settlers living in the village. The storekeeper, John Strike, also took in lodgers, but was unco-operative towards the British South Africa Company's servants and the Postmaster, John Collyer, who later became Postmaster-General had to share a mess with the troopers. All buildings were of the wattle and daub variety, with a tarpaulin provided to give additional protection for the post office apparatus. Although these huts were cool in summer and cosy in winter, they lacked any comforts. The windows were formed of calico stretched over wooden frames, and the bath water was heated in paraffin tins over an outside fire. Hurricane lamps were used, and most of the furniture was made from paraffin boxes, a practice which continued in Rhodesia for many years. When these boxes were discarded by the fuel companies in favour of the more conventional pumps, it was a sad day for Rhodesia's amateur carpenters.

Figtree’s Anglican Church

The Anglican Church today is mostly used by the pupils from Figtree Primary School.

The Anglican Church opened Cyrene mission east of Figtree in 1939. It was a bold experiment in native education. The director of the mission was the Rev. Edward Patterson, who had previously served with Bishop Paget, Archbishop of Central Africa, when he was still a priest in Benoni in the Transvaal. The Rev. Patterson had a special talent in art and set about developing the African talents in arts and crafts, a task in which he was singularly successful, and he demonstrated the African's natural ability in wood carving. The work was so successful that an exhibition of Cyrene art was held in London during 1949, and another in 1954 - an exhibition which did much to bring the Rhodesian African Art to the attention of the outside world. See the article The historic and world-renowned Cyrene Mission and its Chapel face the threat of an illegal settler invasion under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The Salvation Army also operate an educational scheme called the Usher Institute at Leighwood near Figtree. It was named after J. Usher, a pre-pioneer who was trading at Lobengula's kraal at the time of the latter's defeat in 1893. See the article The Kirby family and their Salvation Army connection in early Rhodesia with the Usher Institute from 1946 and the Tshelanyemba Institute in the Semokwe Reserve from 1948 – 1954 followed by international assignments in Northern Rhodesia, present-day Zambia under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Before the Rebellion, another trader named W.H. Dawes had a store near Figtree at Mabukutwane, on the banks of the Umganen river which he had to vacate during the troubles. He subsequently joined the BSA Police and for many years was stationed at Mphoengs on the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) border. After his retirement, he purchased Glamorgan farm where he lived until his death.

F. R. Barnes, who was Postmaster of Bulawayo during the period 1910-1921 retired on his farm at Figtree, but he was perhaps best known for his exploits during the Mashonaland Rebellion of 1896, when as a member of the Mashonaland Volunteers he was detailed to patrol and repair the telegraph line between Salisbury and Marandellas which was constantly being interrupted by the rebels.

The Connelly brothers, Joe and Redmund, have established one of the best known Hereford herds in Southern Africa.

The main road through Figtree

References

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland. Rhodesiana Publication No 27, December 1972, P1 – 28

P. S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia, 1890-1897.Rhodesiana Publication No 12. September 1965. P37 – 62

Colonel H.G. Seward’s story (Part 2). Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 23, 2004 P84 – 112

Rhodesiana.com. Figtree. https://www.rhodesiana.com/rsr/rsr2-004.html#top

Robert Cherer Smith. Avondale to Zimbabwe: A Collection of Cameos of Rhodesian Towns and Villages

W.M. Grant. Into the Thorns: Hunting the cattle-killing Leopard of the Matobo Hills quoted in African Hunting Gazette. https://africanhuntinggazette.com/into-the-thorns-4/

http://www.nigeltout.com/html/zimbabwe--towards-plumtree.html

[1] Rebellion Forts in Matabeleland.

[2] Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia, 1890 – 97

[3] See the article The Hunter’s Road - followed on maps under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[5] Lieutenant Colonel D Tyrie Laing (Commander of the Body Guard) killed at Lindley, 3rd January 1901 in the Anglo-Boer War

[6] Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia, 1890 – 97

[7] I am not sure this last statement is correct. In 1863 King Mzilikazi had sent an impi of warriors down to the outpost at Makobi in order to issue disciplinary action to the Mangwato people living there. A thousand people were killed and the outpost obliterated. The King ordered a new outpost established.

When King Mzilikazi saw that all the traders, explorers and hunters were using the Hunter’s Road, he established an outpost near the Ingwesi river at Makobi, about 30 miles (48 kms) south of the Mangwe Pass. The people stationed at this outpost were instructed to make sure that no outsider entered the Matabeleland without permission from Mzilikazi. Visitors would stop at Makobi’s whilst messengers went up to Old Bulawayo and sought Mzilikazi and later Lobengula’s permission.

John Lee, who enjoyed a good relationship with both Mzilikazi and Lobengula was appointed as the King’s ‘agent’ to monitor and control the growing stream of adventurers from the south set up his farm on the Mangwe river.

Lee’s farm became a well-known stopping place for all the pre-occupation traders, explorers and hunters. Lee bought and sold spans of oxen; often incoming oxen were worn out after crossing the dry country of Bechuanaland and many travellers enjoyed Lee’s hospitality as they rested their oxen and repaired their wagons. For a description by Thomas Baines of his stay at John Lee’s see the article Thomas Baines journey to present-day Mashonaland: His first journey described from 16 February 1870 to 9 January 1871 (Vol 2) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com