My Matabeleland Experiences (1897-1903)

Introduction

This article was written by P.A. Stuart in the 1942 NADA publication – the Southern Rhodesia Native Affairs Department Annual. It is here copied verbatim with notes and photos added.

My brother persuades me to try Rhodesia

It is perhaps understandable that, as a youth 44 years ago, my contact with Rhodesia "in the raw" should have left an indelible impression on me, The change from an English public school and a short sojourn in Natal, where I was born, was a hefty jump.

It was just that leap in the dark that so often makes a man or sometimes mars him. Life was hard, yes, but always happy and wholesome, despite the somewhat monotonous recurrences of malaria.

But although things were more rough than ready in those days, I feel that I am a debtor to Rhodesia for the experiences which naturally befall any who rub shoulders with the unfamiliar both in man and nature. More than this. It is the inherent lure of the country itself, rather than the mellowness of time, that makes my memories of it entirely happy ones.

In July 1897, C.T., my brother, who was on leave in Natal, persuaded me to throw up my job in the Natal Service. He was N.C. at Nungu, in the Malema district, at the time.[1]

"Why not try your luck in Rhodesia?" he said. I always took C.T.'s advice, and, ten days later, we were in the train for the north.

Travelling in 1897

The extension of the railway to Bulawayo, which was being frantically laid, at a mile a day, had at that time only reached Tati (Francistown). Such was the haste to get the line to Bulawayo in time for the formal "opening" that the metals could not be properly ballasted. They were merely attached to the sleepers (roughly covered with earth) and placed on the hurriedly levelled bare veldt. There were no culverts or bridges. The rivers and streams were negotiated simply by cutting away the banks and placing the metals on the river beds which, at that time of the year, were waterless. This, the latter part of the rail journey, was novel and exciting.

NAZ: Harold Pauling’s construction train arriving at Bulawayo on 19 October 1897

At Tati we boarded a coach drawn by ten mules, and who has not heard of Zeederberg's fine coaches? Normally the coach carried twelve passengers, but this time it took on twenty. Twelve packed inside and eight on top.

As C.T. and I were the last to book we had to fit in where we could, so we wedged ourselves between the mail bags on the roof. A Frenchman, I remember, had found a cosy nook between two large bags, so C.T., to obviate the possibility of being jolted off his precarious perch during the night, took the precaution of fastening a cord to the Frenchman's and his own buttonholes. Thus, if C.T. was bumped off a drop of about ten feet the Frenchman would have to go too! (As I don't speak French I cannot relate the Frenchman's oration when he discovered the ruse)

After 120 miles we reached Bulawayo, dusty, tired and hungry, for we hadn't had a proper meal for two days.

Zeederberg Coach at the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe at Bulawayo - imagine 20 men crammed into and on this coach!

One of the first things that struck me about Bulawayo was the breadth of its dusty streets with pavements (?) lined with young pepper trees. I was amazed, too, at the mushroom growth of so many buildings, mostly of wood and iron. Ninety per cent of the men (very few women in those days) were in riding kit, coatless, sleeves rolled up and nearly all with the Baden Powell broad-brimmed hat. Picturesque figures all and all redolent of a fine camaraderie peculiarly Rhodesian, as I was soon to learn.

For a month or two I stayed with C.T. at Nungu, when, as a result of his good offices and those of the then Chief Native Commissioner, Herbert John (later Sir Herbert) Taylor,[2] I was offered and accepted the post of Assistant Native Commissioner at Gwelo (vice W. L. S. Driver who is here in Durban today)

Appointed Assistant Native Commissioner at Gwelo

Gwelo in those days consisted almost entirely of small wood and iron shacks with a population of about 100 Europeans all told. The names of residents that I can recoil at that time are: Smith, P.O., Magistrate; Darling, R.M,, Clerk; Norris, Commissioner for Mines; Sir Drummond Dunbar, Mines Department; Chawner, O.C., B.S.A.P.; Rev. Walker, Anglican Church; Major Hurrell, Horseshoe Hotel; Muirhead, Areskong, Cumming and Crelin, of Meikle's Store; Longden, Pilkington and Ferguson, Solicitors; Bagnall, Surveyor; Nash and Jordison, Auctioneers; Nimmo and Bridgeman, Outfitters; Finnie, Land Agent; Metcalfe, Postmaster; Reed, Prospector; Toogood, Bank Manager; Dr. Smythe, Medical Officer; Skey, mineral water manufacturer; and McNally, editor, manager, compositor, reporter, office boy and general factotum of "The Gwelo Times."

The only drinking water was from wells. Meat, when obtainable, was 3 shillings per lb. no fresh milk or butter, and fresh vegetables rarely procurable.

My duties as A.N.C.[3] were vaguely defined, but as a kick off it was of paramount importance that I should trace and, if possible, arrest some ten or a dozen of the more notorious ringleaders of the 1896 Rebellion in that district.[4]

I have never tried to find a needle in a haystack, but my efforts to trace those "wanted" men were, I imagine, somewhat akin to that pastime. However, more by accident than design, I succeeded in laying one of these gentry by the heels, and, as it so happened, he was the most "wanted" of them all.

When this man was brought before me I administered the usual caution, to which he somewhat nonchalantly replied: "I have nothing to conceal, and I will tell all, in fact I want the amakiwa (Europeans) to know exactly what happened." He then proceeded to recount, in minute and graphic detail, how he and his "impi" had surrounded and done to death, on the 26th of March 1896, two Europeans and their Zulu servant.

"They were driving," he said, "a donkey wagon laden with sacks of mealies to Koboli (about 18 miles N.W. of Gwelo)[5] The Europeans were sitting on the mealie sacks, the Zulu was on foot, driving. We surrounded them and first shot a donkey to stop the wagon. Then we fired a volley at the three men. One European was killed outright and fell off the wagon. Then the Zulu fell. Next we saw we had wounded the other white man, for as he climbed off the wagon his leg was dangling helplessly. He crawled behind one of the back wheels and from there he fired many rounds at and killed some of my men. But we outnumbered him, and when his ammunition was spent we just rushed in and finished him off."[6]

He concluded his graphic description by exclaiming: "Yes, we finished the amakiwa off and we were satisfied."

At that, my hotblooded youth got the better of me, and (very wrongly) I exclaimed: "That is enough! You will hang for this!" To which he replied, quite calmly and quietly: "Never! No white man will ever hang Gwaibana!" (for that was his name) In due course he was tried for the murders, convicted and sentenced to death.

But in those days a capital sentence required written confirmation from Cape Town,[7] and this took anything from a fortnight to a month to arrive. In the meantime Gwaibana was incarcerated in the local gaol about fifty yards from my office. Some days later the gaoler told me that Gwaibana was getting markedly thinner and that special diet had been prescribed for him. But it was no good. Gwaibana daily became weaker, and, three days before confirmation of the sentence arrived, the gaoler rushed into my office, "Gwaibana is dead." "No!" I exclaimed. "Yes, come and see him."

I went, and there I saw Gwaibana, very still and cold in his cell but with a broad grin on his face!

I learnt subsequently that he had petered out as a result of slow poisoning. He had, through one of the other prisoners, got hold of some indigenous herb which, when swallowed, causes emaciation and finally death. This was surmise, but surmise or not, Gwaibana's boast that no amakiwa would ever hang him was well founded.

A Transport Driver's brush with lions outside Gwelo

One morning early I was working at my office when a man burst unceremoniously in: "Brandy! quick brandy! "

"What's the matter?" I asked anxiously.

"Brandy! Brandy!"

I ran out and got the liquor, which he gulped down.

"Come, tell me," I asked again, "what has happened?"

"I've just shot four lions two miles from here, and this is the first time I have ever even seen a lion!"

Such was the feat, the incredible bag, four lions before breakfast, accomplished by "Masher" White, transport rider on the main road from Gwelo to Bulawayo.

Lions were very much "de rigueur" in the Gwelo district in those days. I myself came across their spoor more than once on the Gwelo cricket ground.

A lion attack on an African kraal

I was a keen collector of wild game trophies and had made it known to the natives that I would buy any horns or skins they might wish to sell.

One day two men came in and, on asking their business, they said they had brought me a lion skin as a present. Surprised at this unexpected generosity, I asked to see it. They undid a bundle and laid out on the floor the most dilapidated skin of "Felis leo" I have ever seen. It was a mass of Mbembe (battleaxe) holes. Their story was this: two nights before, with the moon at the full, all members of the kraal were in their huts getting ready for bed. As it was hot, all doors had been left open. Suddenly a piercing cry rent the night. "I am dying! A lion has got me. Help! Help!"

In a twinkling every man darted out with his battle axe, and there, in the bright moonlight, they saw a full grown lion mangling one of the old men. Like a flash a young fellow leapt at the beast and gripped it firmly by the root of the tail. "Quick, quick!" he shouted, "kill it while I hold it!" And kill it they did. The multi-punctured skin was eloquent evidence of their valour and of that of the young man. From this incident I gathered that it is customary (or was) In that part of the country to make the old folks sleep nearest the door as a safeguard against such eventualities as this!

Assiatant District Commissioner at Nyati

It was in 1898, I think, that I relieved C.L. Carbutt (A.N.C. at Nyati, 45 miles north of Bulawayo)

A few miles from the camp there was a trader who sported a tame guinea fowl. That it was tame was remarkable enough. But, when the owner told me that if he wanted a guineafowl for the pot he would take the tame guineafowl out with him as a decoy to call the wild birds to his gun, Well, when he told me that, I just didn't believe him and said so. But seeing is believing. He whistled for the tame and trained bird and instantly it trotted up in proper guineafowl fashion.

Picking up his shotgun the trader asked me to accompany him. As we struck a path the guineafowl took the lead. Yes, trotted in front and presently began calling as only a guineafowl can. But although we had no luck, I apologised to the trader for doubting him. I believed then, and still believe, that he used that foul method of luring innocent, if wild, guineafowl within range of his gun and pot.

A Policeman's demise

It was at Nyati one morning that a B.S.A. Policeman galloped into my camp. He quickly explained his haste: A trooper (a man called Preston, I remember) had just shot himself by accident through the upper part of his leg. Would I please hurry down to the camp and advise them what to do? I jumped on my horse and together we galloped to the camp two miles off.

There I found poor Preston, white as a sheet, lying on a canvas stretcher, bleeding profusely, with half a dozen men standing round helpless. But what could I do? I knew nothing of first aid. The nearest doctor was 45 miles away at Bulawayo, and the nearest telephone (at Fincham's farm) was six miles off? But instant action was imperative.

I sent a man post haste to Fincham's to phone for a doctor. Preston couldn't be moved, his agony was too great, so snatching a razor I climbed under the stretcher and cut away the canvas opposite the wound. Through the opening I covered the bullet hole with a cloth pad, then bound the whole wound tightly with many yards of bandages. Then we put him on a spring stretcher which we tied on to a donkey wagon, the only transport available and sent it off, at donkey pace, to Bulawayo. That crude ambulance had travelled 25 miles before it met the doctor. But it was too late. Preston had died. A tragedy, yes, but Rhodesians faced these things then, as they do today, like men.

A tribesman's encounter with a leopard

On one occasion, while on patrol in the Gwelo district, I arrived at a kraal to find a man skinning a leopard. I quickly offsaddled, not only because I scented a story behind the killing of the cat, but because the man skinning it had had the whole of his upper lip torn away. I thought, at first, that the leopard had been responsible for this, but I soon saw that the grinning scar was an old one.

"How did you come to kill the leopard?" I asked him. He pointed to a hut; one of those contraptions that one occasionally sees built on solid rock in Rhodesia.[8] “Well” he said, "this leopard chased my wife into that hut and the door swung closed, caging my wife and the leopard in there together. I heard her screams, and through that opening you can see (an air vent in the wall about six inches square) I killed the leopard with my assegai."

"And your wife?" I asked. "Oh, yes, she was badly mauled, but she will recover. But this leopard he won't hurt her again," he concluded, his grinning teeth belying the anger in his eyes.

"And your own misfortune?" I enquired, my eyes sympathetically on where his upper lip should have been. "Oh, you mean this!" he was still grinning. "This is nothing. Twenty years ago I stole a goat, and my chief made me pay for it with my lip. He had it cut off as you see, and I have been laughing ever since."

The zebra that disappeared at Somabula Forest

The Native Commissioner under whom I once served at Gwelo was the late F. G. Elliott, a lovable man and as good a shot with the rifle as he was a comrade.

He was on patrol one day near the Somabula Forest.[9] It was hot and sultry. Suddenly he saw about three hundred yards away, a single zebra standing listlessly under a tree. Elliott jumped off his horse and took his unerring bead on the animal. He fired and, to his amazement, the zebra simply vanished. It didn't gallop off or fall or do anything orthodox. It just disappeared. F.G. stood open mouthed, gazing at nothing! Then he jumped on his horse and galloped to where the zebra had been. The riddle was at once solved. It had been standing beside an old working, a hole some ten feet in diameter and six feet deep; not visible from where Elliott had fired. Instantly killed by the bullet, it had toppled over into the hole. Elliott called up his boys, and in a few minutes they pulled the carcase out. But there was another mystery no bullet wound could be found! Elliott and the boys were dumbfounded. But when they came to skin the animal they found the answer to the conundrum. It was this: as the zebra had been standing he occasionally swished the flies off his back with his tail. At the psychological moment of one such swish Elliott had fired, and the bullet struck the beast immediately under the tail and embedded itself in the spine.

Elliott himself told me this story. I often played with his children on that skin, the skin of a zebra killed with a bullet, but with no bullet hole in it, though he could proudly show the bullet itself which had done the trick!

An incident at Rhodes' funeral in 1902

Leo Robinson, A.N.C., Mzingwane, was a contemporary of mine. One seldom saw him without a shot gun. But, as I have reason to remember, the weapon could be fired only from a single barrel, the trigger of the other was missing. Robinson, with his shot gun as usual, attended Rhodes' funeral.

After the ceremony, some 20 head of cattle had to be slaughtered to feed the thousands of natives present. But no one had been assigned to do the killing, so Robinson stepped into the breach with his single-barrelled shot gun. (In parenthesis my advice to all would be slayers of the bovine species is not to embark on the process with single-barrelled shot guns or even treble-barrelled ones. The animals don't like it, nor do the onlookers) At the first shot the bullock shook his head in dissent. At the second he put his head down and charged! I won't attempt to describe the commotion that bullock created. It is sufficient to say that what followed was striking corroboration of the Darwinian theory, for no apes could have shinned up trees more nimbly than we did! Then a B.S.A.P. man came along and settled the bout in twenty rounds.

Rhodes meets Faku, the amaNdebele Chief, at his Matobo Farm

Talking of Rhodes reminds me of a story of the founder told me by my brother, C.T.

Photo courtesy of Darrell Plowes: reconstruction of Rhodes’ Summer House, Matobo Farm

Rhodes periodically visited his Matopo (Matobo) farms accompanied by a party of men as guests. As Native Commissioner of that district C.T. was once invited by Rhodes to a dinner at the huts.https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftnref10" title="">[10] During the repast the question of supplying liquor to Natives cropped up, and Rhodes, turning to his Secretary (it was Grimmer, I think), said: "I say, Grimmer, what would you do to me if I gave my boy a tot of gin?" His secretary wouldn't have done anything and said so. Rhodes then turned to C.T. "And you, Stuart, what would you, as Magistrate, do to me if I gave my boy a drink of liquor?"

"The fine is £400, Mr Rhodes," C.T. replied. Oh, so you'd fine me £400, would you?" "That is the penalty, Mr Rhodes."

The subject dropped. Next day there was a big indaba between Rhodes and the natives of the district, and C.T. was there in his official capacity and did the interpreting. Halfway through the "powwow" an elderly Native hobbled up and, seating himself opposite Rhodes, cupped his hands over his eyes the better to gaze on the great man.

"Who is that?" asked Rhodes. "His name is Faku," C.T. answered. "Where does he live?" "Over that hill, six miles away."https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftnref11" title="">[11]

"What has he come here for?" After enquiring, C.T. replied: "He says he has come to see you." "And how has he travelled here?" "On foot." "On foot? How old is he, Stuart?" "About eighty."

"What, do you mean to tell me that that old man of eighty has walked six miles to see me?" "That's what he says." Rhodes swung round to his manager. "Here, get me a tumbler of gin." The manager brought it and handed it to Rhodes.

"Now, Stuart, if it is going to cost me £400, Mr Faku is going to have this glass of gin," and he stepped forward to Faku, handed him the liquor and made him drink it.

Patrol into the Northern Transvaal (present-day Limpopo Province) during the Anglo-Boer War

In 1899, I was stationed at Manzimnyama, in the Gwanda district, vice P. Nielsen, transferred.

About 9 pm one night I returned from a trip to find installed and asleep in my bed the Chief Native Commissioner. He shortly explained the object of his visit. I was to recruit 30 native scouts at once, arm them each with a Martini-Henry and 50 rounds, plus rations, etc., and report with the least possible delay to Captain (I think his name was McLaren), the officer in command at Macloutsie. From him or Colonel (later Field Marshal) Plumer I would get full instructions as to what I was to do. The Boer War had then been in progress about three weeks.

In three days I was off. The first day out before I had left the main road to strike across country l was overtaken by a mule wagon conveying Captain Tyler and Lieutenants Ffrench and Bunt (all from overseas) to Fort Tuli. They pulled up and we had a chat.

All three officers were bored stiff, they said, at having been drafted to Plumer's Column. "We'll never see a Boer in this Godforsaken country. We came out to fight, not to meander around off the map. The war will be over in no time and we won't even hear a shot fired," and so on. Their talk was depressing.

Within three or four months two of them had been killed in action. Tyler, I think, was with Spreckley's Column.https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftnref12" title="">[12] A pompom shell decapitated him his headless body standing erect for a moment, then crashed to the ground, so an eyewitness told me.

As for Ffrench, this is the story told me by H. Greer, then a clerk in the N.A.D. Incidentally, I may mention, Greer related the whole story in Zulu. It was wonderfully and dramatically rendered by a splendid Zulu linguist, and it gained, rather than lost, by its rendition through that medium. Greer joined up, and one of his officers was this Lieutenant Ffrench. The Boers were entrenched on a kopje and barred the Rhodesian Regiment's advance southwards towards Mafeking. The order was given that the kopje must be attacked at dawn next day. The attack was made, Ffrench in the van. At the first glimpse of dawn the troops surrounded the [Boer] fort and crept noiselessly up. Near the top they were stopped by wire entanglements. Ffrench jumped forward with wire clippers and began cutting his way through. There was not a sound, but the snipping of the clippers.

Then, suddenly, a murderous volley cracked out from the Boers. Many of our men fell. But Ffrench, as yet unscathed, went doggedly on with his job. A moment later the Boers spotted him and their next volley concentrated on him. The gallant officer fell a riddled corpse. The Rhodesian force retired, and later a truce to bury the dead was agreed upon. When they reached Ffrench's body they found a rough cross erected beside it on which had been inscribed this epitaph: "Here fell the bravest man in the British Army."

After three days at Macloutsie, Plumer sent a message ordering me to report at Tuli with my scouts as soon as possible. Within 24 hours my 30 scouts, each laden with 40 lbs. of rations, rifle and ammunition, had covered the 60 miles to Tuli on foot. It was a fine feat, and Colonel Plumer was as amazed at it as I was. My instructions were to scout the main road from Boer Pont to Pietersburg (120 miles) I covered half that distance into the Transvaal without any spectacular results. But it was interesting and, at times, exciting as, for instance, when a Boer patrol passed my camp in the bush within 50 yards and never saw it!

Another interesting occasion was when I captured two native spies, armed with "Z.A.R." rifles. By threatening to shoot them I made them give me much valuable information, which I passed on to the O.C. and which subsequently proved to be correct in every detail. I also captured some cattle and mules and did other sundry jobs of that sort. Nothing much to talk about, I know, but still, taken as a whole, it was an experience, and one more to my liking than the humdrum life of an office.

Fort Usher and Kumalo's miraculous escape from the firing squad

On my return to the more servile civil life I was stationed at Fort Usher, then under the guiding hand of Hugh Morrison Gower Jackson, a name as long as he was tall. The Natives called him "Matshayisikova" (also pretty lengthy), which, as every linguist knows, means "The Smiter of Owls." H.M.G.'s interpretation of the appellation was "Do good by stealth" (in the dark like an owl)

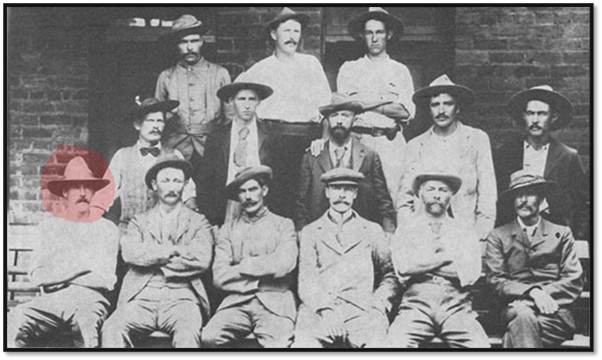

NAZ: Native Commissioners in 1896. Back (L-R) T. Hepburn, D.H. Moodie, C.G. Fynn

Middle (L-R) E. Armstrong, B. Armstrong, C.B. Cooke, V. Gielgud, T. Fynn

Front (L-R) H.M.G. Jackson, W.E. Thomas, H.J. Taylor, Capt. The Hon A. Lawley, J.W. Colenbrander, unknown

While at Fort Usher, I was one day having a chat with the Sergeant Major of the police at the camp when two troopers, escorting a native prisoner, passed in front of us.

"Do you know who that prisoner is?" the Sergeant Major asked me. "No, who is it?" "Why, that's Kumalo, you must have heard of him the notorious Kumalo, you know." "For what was he famous?" "It's a long story, but, briefly, here it is: Kumalo is a Zulu, but in the Rebellion he sided with the rebels. He had influence with the natives and we looked upon him more or less as a traitor, and there was a big price on his head. We tried for months to run him to earth, but he was too smart. Then at dusk one evening a couple of men caught him and brought him into camp. I rushed to the orderly room, saluted the O.C. and stood to attention.

“What is it, Sergeant Major?” the O.C. asked. “We have caught Kumalo, sir.” “No! Are you sure?” “He is under arrest outside, sir.” The O.C. was about to reply but suddenly checked himself and instead drummed nervously with his pen on the table. Then he looked up at me. “Sergeant Major.” “'Yes, sir.” “I don't want to see Kumalo, you understand? Ever.” I hesitated, not understanding. “I don't want to see Kumalo ever again, Sergeant Major never again,” then with greater emphasis he repeated “Never again, is that clear?” I stood, still open mouthed. "Take him away, Sergeant Major, don't you understand? I don't want to see Kumalo ever again!” he shouted at me.

Then I tumbled to it. Kumalo's was a case for the firing squad and It was my job to see the business through, and so, saluting, I went out. The sun had gone down; it was getting dark. In a jiffy I had four troopers before me with their rifles, two on either side of Kumalo and I marched them out along a path into the veld. In ten minutes we had gone far enough and you could hardly see in the gloom. “Halt!” I ordered. Then moving Kumalo half a dozen paces forward, I returned to the men and gave the command Fire!' Kumalo fell, face downwards and lay motionless. “Right about turn quick march,” I commanded.

Arriving back at camp I rushed breathlessly to the orderly room and, in panting jerks, blurted: “Prisoner Kumalo tried to escape, sir, we shot him dead.” "'What!' he said with well simulated horror, then quickly, far too quickly recovering himself: “All right, Sergeant Major, dismiss.”

As the Sergeant Major finished his story, I said: "But I don't understand. You told me just now that the man who passed before us a few minutes ago was Kumalo himself, alive and kicking?"

"Quite so. But come along with me now and have a look at him. I'll explain." Kumalo grinned as we came up and continued to smile as we examined the four bullet wounds, one of which had grazed his head and the others in non-vital spots the sum total of the firing squad's effort four years before. Stunned, and grievously hurt, Kumalo had nonetheless been able to crawl away in the dark to safety. Although arrested four years later, he was eventually liberated, and, for all I know, may still be in the land of the living.

It was in the Nyati district that I bumped into a man called Carruthers, a transport rider. Over a tin of bully beef we swopped yarns. Somehow the conversation veered to athletics. I rather fancied myself as a runner in those days and, youth like, it was not long before I had regaled Carruthers with my performances on the track. When I had finished, he knocked out his pipe, slowly refilled it, lit up, and, after a couple of puffs, said: "Yes, running on a well prepared and level track is good fun. You have the crowd's plaudits to spur you on, then there's the prize and, above all, there is the satisfaction of something achieved if you are the first to breast the tape."

He paused, took a couple more puffs, then went on: "But look here, the finest athletic competition of all is to run for your life not on a track, but up and down the boulder strewn hills of Matabeleland not for half a mile or so but for ten miles and more, with a dozen assegais behind you to keep you up to record time, and…" "Half a moment," I interrupted. "What are you talking about?"

Carruthers escapes from certain death in the 1896 Matabele Rebellion

At midday on the 26 March 1896,https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftnref13" title="">[13] I was prospecting some 25 miles from Bulawayo. Suddenly there appeared on a ridge three or four hundred yards away a party of about a dozen Matabele. As they were armed, and as there had been vague rumours recently of a native rising, I didn't like the look of things, not a little bit. So, without making too much of a fuss, I started to move off. They shouted at me: “Don't go away, white man; we want to speak to you.” I stopped and shouted back in their own language, for I speak it well: “Tell me from where you are, what it is you want.”

They replied: “No, you wait there. It is only a small matter of which we wish to speak.” That was enough, more than enough for me. I turned and ran. I was carrying a rifle and ammunition and, of course, I had boots on. But I ran. I realised at once that if I were to get through alive it was no sprinting match from there to Bulawayo. So I settled down to a steady, brisk trot. With a yell the savages were after me. At first their shouts came nearer and nearer, but I quickened my pace and I don't think they ever got within two hundred yards of me. My rifle and ammunition were getting very heavy. I flung them away. Then as I ran, I threw off my coat. Thank my stars I was in good fettle!

But running in boots is a big handicap. But I kept on, with those devils shouting tauntingly at me. After about six miles their shouting ceased. I looked back, and, to my relief, I saw that they had stopped. There were only three of them now, so I stopped too, sat down on a stone and pantingly watched them. That short rest was a godsend! I could hear them talking but couldn't distinguish the words until presently one of them shouted to me: “Bale kagundwana!” (Run away you rat!) But rat or no rat, I had outdistanced them and I took the taunt as a compliment. They turned slowly and retraced their steps. I continued on my way, and, after a couple of hours, I jogged, somewhat wearily, into Bulawayo and here I am today! To me this epic race for life by Carruthers was on a par with the original Marathon. All natives are good long-distance runners, but Carruthers, handicapped by boots, eclipsed them all that day.

Travelling on the Zeederberg Coach and an uncanny coincidence

While stationed at Gwelo, I went several times to Bulawayo by coach. The journey usually occupied about 24 hours in dry weather. Except for changing mules (each team a set of ten fine animals) every six or eight miles, it was a nonstop run.

I always enjoyed these trips. They were very dusty and tiring, naturally, but somehow the dust didn't taste or smell the same as that of more Southern Africa, and the fatigue one felt, though trying enough, was quite different from that of all night in the train for instance, or a gruelling day in the saddle. There was a peculiar tang about these discomforts that made them easier to bear. Altogether the journeys made an impact on one's senses, including sight and sound, that was pleasant and interesting. Yet the roads were execrable: simply wagon tracks on the bare and sandy veld.

On one of these trips I was one of 16 passengers to board the coach at Bulawayo. We left, I remember, at 6pm. About ten o'clock we pulled up at a wayside store and another change of mules. Refreshments were obtainable at most of these stops, and very acceptable they were! We all trooped into the "buffet" a single, wattle and daub room, with bare mud walls, un-ceilinged and with a thatch roof. A counter of rough packing cases ran across one end. Lighted candles, stuck into empty bottles, flickered gloomily, giving a somewhat sanctimonious background to the scene.

Everybody ordered coffee, and, as I was drinking mine, one of the passengers walked up to me and, with his cup, pointed to the old school cap I was wearing. "Excuse me, were you ever at school at Hurst?" "Yes," I replied. "Why?" "Because I went there myself! Shake!" Our hands instantly gripped, but before we could say anything another man standing a yard away watching us exclaimed: "By jovel so did I!"

And thus it transpired that the three of us, all total strangers, had been educated at the same public school in far away England and had met there, on that outlandish spot, for the first time and under those circumstances. There was something of the uncanny about the coincidence! The man who first addressed me was Mitchell (I think his initials are C.F.) then in the B.S.A. Police, while the other was Holland, the then Mayor of Bulawayo.

The perils of "penny nap"

Towards the end of 1901 I left for Natal to get married. The Boer War was still on and trains were allowed to travel only by daylight. The journey to East London occupied 13 days. When I arrived there I had exactly 2/6d in my pocket for the rest of my ready cash had gone in "penny nap" (and pound foolish) with which we had beguiled the hours of that tedious journey. I hailed a cab, and for driving me to Deal's Hotel the cabby charged me my last half-crown.

I booked a room, had a wash and brush, then sat and I pondered my position. My boat for Natal was to leave next day, but I hadn't the wherewithal to book my passage, and I had never been in East London before. I took a beeline for the Standard Bank and asked to see the manager. I told him the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and wound up by asking him to advance me £10. My self-confessed gambling propensities would not, I knew, prove an open sesame to the bank's coffers. But, I argued, I had ample funds in the Bulawayo Branch and surely it would be a simple matter for East London to wire to Bulawayo to get confirmation of my affluence and so pave the way for the advance of that very much wanted £10?

"That's no good," the manager said. "How can I tell that you are not impersonating the man you say you are?" That was a poser. But, undeterred, I replied: "Anyhow, it is highly necessary that I should be present at my wedding; the boat leaves tomorrow, and I simply must have that £10."

He surveyed me for a moment, then asked: "Have you your cheque book with you?" "Yes, I've got it here." But it wasn't in my pocket. "I must have left it at the hotel. I'll run and get it." Back at the hotel I searched my suit case, but no cheque book! I went back to the bank and again told the truth. This time I got a more piercing look from the manager. Then suddenly he demanded: "Let me see your handkerchief." I gave it to him, and he searched for my name on it, but it was nameless.

"Do you know anybody in East London who can identify you?" he asked. I thought furiously for a second, then triumphantly: "Yes, I know a Mr H. Tilney who lives here. He is a brother of W.A. Tilney, who is a native commissioner with me in Rhodesia. "I knew Mr H. Tilney, too," he replied, "but unfortunately he died here in East London quite recently." My luck seemed to be clean out. I stood there speechless. But after sizing me up once again the manager pressed the bell on his table and a clerk entered. "Give this gentleman £10." And a minute later the clerk counted into my palm the most golden sovereigns I had ever seen.

I quote this experience because bank managers, in these more sophisticated days, are not so kindly disposed towards penniless gamblers.

But however that may be, I have always thought that that bank manager's kindly consideration was largely, if not entirely, due to Rhodesia's hallmark on my otherwise unprepossessing physiognomy. Good old Rhodesia!

A tragedy leads to Stuart and his wife leaving Rhodesia

In 1902 my first child, a son, was born in Bulawayo. Four months later he died. He lies buried in a Bulawayo graveyard, and so, although his passing was largely responsible for my leaving Rhodesia, I derive some consolation from the knowledge that a part of me is in Rhodesia still and with this extra tie to urge me, I cannot more fittingly conclude these ramblings than with the prayer FLOREAT RHODESIA.https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftnref14" title="">[14]

References

NADA: The Southern Rhodesia Native Affairs Department Annual for 1942. https://archive.org/details/TheSouthernRhodesiaNativeAffairsDept.AnnualF...">https://archive.org/details/TheSouthernRhodesiaNativeAffairsDept.AnnualF...

R. Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, Salisbury 1975

Notes

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn1" title="">[1] This location has not been identified

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn2" title="">[2] See the article The inauspicious start to Herbert Taylor’s thirty-three year career as Chief Native Commissioner under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com/">http://www.zimfieldguide.com/">www.zimfieldguide.com

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn3" title="">[3] A.N.C. Assistant Native Commissioner

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn4" title="">[4] See the article Rebellion days in Bulawayo: When the Matabele rose in 1896 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com/">http://www.zimfieldguide.com/">www.zimfieldguide.com

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn5" title="">[5] There is no present-day Koboli to the northwest of Gwelo (present-day Gweru) but the small Fort Ingwenya goldfield is approximately 25 miles (40 kms) from Gweru and they were probably travelling on the ox-wagon track to this place. See the article Fort Ingwenya and Cemetery under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com/">http://www.zimfieldguide.com/">www.zimfieldguide.com

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn6" title="">[6] See the article on the Gwelo (present-day Gweru) Rebellion memorial outside the Zimbabwe Military Museum Gweru Memorial (Matabele uprising, or First Umvukela, 1896) under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com/">http://www.zimfieldguide.com/">www.zimfieldguide.com that lists many of those soldiers and civilians killed in 1896

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn7" title="">[7] High Commissioners for Southern Africa at the time were: Sir Hercules Robinson until 21 April 1897, William Goodenough (acting) until 5 May 1897 and Sir Alfred Milner from 5 May 1897

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn8" title="">[8] Usually these are grain bins designed to keep rats and vermin away from their grain store

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn9" title="">[9] The Somabula Forest is situated near the Ngamo and Gwelo rivers, and the Vungu river, north and west of Gweru

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn10" title="">[10] See the article Rhodes’ Summer House under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com/">http://www.zimfieldguide.com/">www.zimfieldguide.com

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn11" title="">[11] Faku was an important amaNdebele chief of the time

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn12" title="">[12] John Anthony Spreckley C.M.G. (1865 to 1900) Attested 30 May 1890 as paymaster Sergeant in the Pioneer Corps (No 150) Emigrated to South Africa from England in 1882 and. Worked on an ostrich farm at Fish River near Grahamstown from 1881 to 85. Had a short stay in Barberton during the gold rush after which he joined the Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP) as a corporal. Resigned in March 1887 to join Borrow, Johnson, Heany and Burnett on an expedition to Bulawayo to obtain a gold concession from Lobengula. Returned to Kimberley in December 1887 and then worked in Johannesburg on the gold mines from 1888 to early 1890.

After being demobbed from the Pioneer Column he prospected in the Sinoia (Chinhoyi) area and was appointed mining commissioner in the Lomagundi district in June 1891. In 1893 he was appointed a magistrate at Umtali and in August 1893 appointed captain and OC of C Troop of the Salisbury Horse.

Took part in the actions at Shangani on the 24 October and at Bembesi on 1 November in the invasion of Matabeleland. Appointed magistrate at Fort Victoria in January 1894 before resigning from the chartered company and joining Willoughby Syndicate in August 1894 becoming general manager of Willoughby's Consolidated in 1895. Appointed Captain in charge of C Troop, Matabele Regiment during the Matabele Rebellion and then Colonel in command of the Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) And appointed C.M.G, on 5 May 1897. Served as two i/c to Colonel Plumer on the march from Tuli to the relief of Mafeking on the 17 May 1900 before given command of the Rhodesia Regiment. Killed in action at Die Klip drift north of Pretoria on 20 August 1900.

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn13" title="">[13] This was very early in the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) when the first murders were being committed. One hundred and forty-five settlers were killed in Matabeleland during the Uprising, or Umvukela of whom the great majority of one hundred and twenty-one were killed between the 23 – 31 March 1896

https://d.docs.live.net/37E3638DD24AEB88/Documents/Documents/22Snips%20-..." name="_ftn14" title="">[14] "Floreat Rhodesia" is a Latin phrase meaning "Let Rhodesia Flourish" that served as the motto for the historical region of Rhodesia, present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia. The Latin phrase "Floreat" meaning "may it flourish," "let it prosper," or "may it be successful”

The Umtali (present-day Mutare) Great War peace medal was issued in 1919 after WWI. It was copper, 33.7mm wide and weighed 15.6 gms.

Obverse.; A kneeling soldier, he shield at his feet, presenting his sword to a seated winged angel holding a dove. At her feet, a child holding an olive branch. Above, clouds and the radiant sun. In the exergue, two doves holding, in their beaks, a scroll inscribed; PEACE

Reverse; Within a wreath of Laurel (left) and a palm frond (right) the coat of arms of Umtali with lion Crest and motto: FLOREAT UMTALI. Superimposed above, a banner: TO COMMEMORATE THE VICTORIOUS CONCLUSION OF THE GREAT WAR